July 1942. Sevagram Ashram, central India

daily express reporter: Mr Gandhi, you have been in London yourself. Have you no comment to make on the heavy bombings which the British people have sustained?

mahatma gandhi: Oh yes. I know every nook and corner of London where I lived for three years, so many years ago, and somewhat of Oxford and of Cambridge and Manchester too; but it is London I specially feel for. I used to read in the Inner Temple Library, and would often attend Dr Parker’s sermons in the Temple Church. My heart goes out to the people, and when I heard that the Temple Church was bombed, I bled.

On 29 September 1888, an Indian teenager with a mild case of ringworm and a fine head of hair sailed into the Thames Estuary. He was wearing a white flannel suit that would soon become a cause of enduring shame. As the estuary narrowed after Canvey Island, the SS Clyde was forced sharply south, before heading west again, towards London – and the flat muddy shorelines of Kent, on the left, and Essex, on the right, were now visible. The busy Kentish town of Gravesend, with its cast-iron river piers and its Pocahontas church (the ‘Indian’ princess was buried there), soon hove into view. But the Clyde and the teenager were bound for more modest Tilbury on the Essex shore – and for the new port that had just been built to relieve pressure on London’s more proximate docklands.

In the late 1880s, Tilbury became London’s most important passenger terminal. The Windrush and its Jamaican migrants would dock here in 1948, and it was where many other migrants, such as the ‘Ten Pound Poms’, would leave Britain for Australia. Today, apart from the occasional cruise ship, passengers are unseen at Tilbury. And the only easy way to approach Tilbury by boat these days is the oldest: the foot ferry from Gravesend that has existed since at least the seventeenth century.

‘Single or return?’ asked the flat-voiced man sitting at a small desk in the ferry’s only cabin.

‘Single.’

‘Single is three pounds fifty. Return is three pounds.’

‘Single.’ I wasn’t really listening.

‘Are you sure?’

And then I realized.

‘OK. Return, then. That’s a bit odd.’

He gave me an old-fashioned look.

‘I don’t make the rules, do I?’

I grinned and looked around. Another passenger tittered. I sat down beside her and her shopping bags. She asked me where I was going.

‘Tilbury.’ I giggled. We were all going to Tilbury.

‘Yes, Tilbury.’ I continued. ‘A long time ago Mahatma Gandhi went to Tilbury by boat.’

‘From Gravesend?’

‘No. From India.’

She was silent, and thoughtful.

‘He’d have been a bit chilly. In that loincloth thing.’

‘Actually, he was wearing a white flannel suit.’

‘Oh. Then it wouldn’t have been so bad.’

I went on deck and was able to make out the three-domed Sikh gurdwara (completed in 2010), punching its way clear of the old Gravesend skyline. On the Tilbury side, the ferry slid past a coastal fort (completed in the 1680s), with a curved masonry gateway rearing out of the marshes. I wondered if Gandhi noticed the gateway, so similar to those in early colonial settlements in Gujarat or Bombay, or was he already preoccupied with his blessed suit, or with finding the railway station that would take him to London? And then we gently struck the landing jetty, and I was brought back to earth.

Ahead of me was the old railway station, abandoned in 1992, the main building still standing – the platforms now an unused car park, its pristine emptiness protected by harpoon-like palisades and coils of razor wire. I would have to walk to the main station in Tilbury town. The old railway siding, further inland, was now stacked high with shipping containers and, closer to the estuary, I could see the modern port, with huge blue cranes, a great mountain of shiny twisted scrap metal – and three spinning wind turbines.

I pushed on into Tilbury, along Calcutta Road, and peered inside an ‘Indian’ restaurant near the station, Le Raj. The waiter, from Bangladesh, couldn’t tell me why it had that name, but said the ‘le’ should be pronounced ‘lay’. I bit my tongue and smiled.

‘Not many Asians around here,’ he said. ‘Mainly blacks and whites.’

He showed no interest in the fact that Gandhi had passed through Tilbury. I was beginning to lose interest myself. So I told him the story. How Gandhi wore a white flannel suit on the advice of his Bombay friends, and was mortified on arrival in England to find that no one else was dressed in a similar manner. He talked of ‘the shame of being the only person in white clothes’, and then, even worse, how he couldn’t get his luggage delivered because it was the weekend,

and so he had to remain in his embarrassing flannel suit for two more days.

‘What is flannel?’ the waiter asked, as he washed some beer glasses.

‘Like cricket clothes, a bit.’

‘Oh. Did he play cricket?’

‘No, he didn’t. Can I order some food?’

‘No, it’s a Tuesday. We’re closed.’

‘Oh, OK.’

I left, walked across Dock Road and, like Gandhi, an eighth of a millennium earlier, took the train to London.

Mohandas Gandhi, the youngest son of the former prime minister of a small princely state, had come to England to study law, in the belief that a London legal qualification would improve his career prospects in India. And he was wildly excited, despite several embarrassing incidents, including the white flannel suit episode, to be in the largest city in the world, the city he would describe as ‘dear London’ and ‘the centre of civilization’. He had taken a considerable risk in coming to London, defying his caste elders and borrowing money to finance his stay. He was leaving behind his wife (Gandhi and Kasturba were married as thirteen-year-olds) and their baby son. His father had died two years earlier, and he would never see his mother, Putlibai, again. She had made him swear, before he left India, that he would not touch meat, alcohol or women. And so far, despite temptations on all three fronts during the journey from Bombay to Tilbury, he had kept that vow. There would be further such temptations.

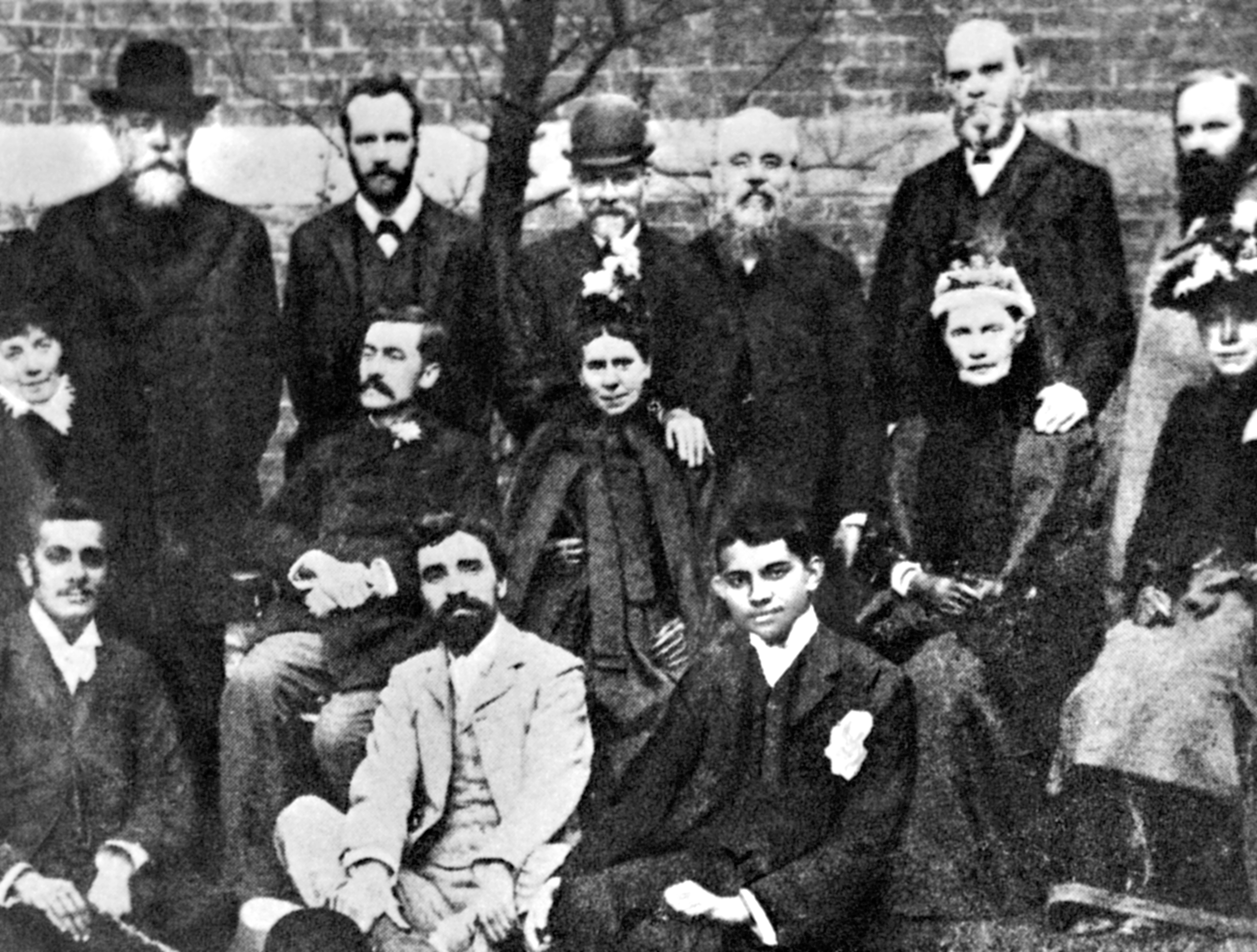

Gandhi’s London years have often been skated over, or deliberately ignored. They are entirely missing from the celluloid, Richard Attenborough version of his life, a film that sadly seems to provide the modern world with its canonical depiction of the Mahatma. Some of his hagiographers seem a little uncomfortable with Gandhi’s antics in London, that he showed so little interest in Indian nationalism, or in politics in general – and that he took dancing and violin lessons, that he professed a desire to be ‘an English gentleman’, that he flirted with young women. But not Gandhi himself, who was always keen to reveal to the world his mistakes and his peccadilloes. And most important it was in London, of all places, that two key strands of Gandhi’s ideas developed, ones that would later be more closely associated with the land of his birth: he became a proselytizing vegetarian, and first showed interest in Hindu religious philosophy. The catalysts in both cases were English friends whom he had met in London.

Sign in to Granta.com.