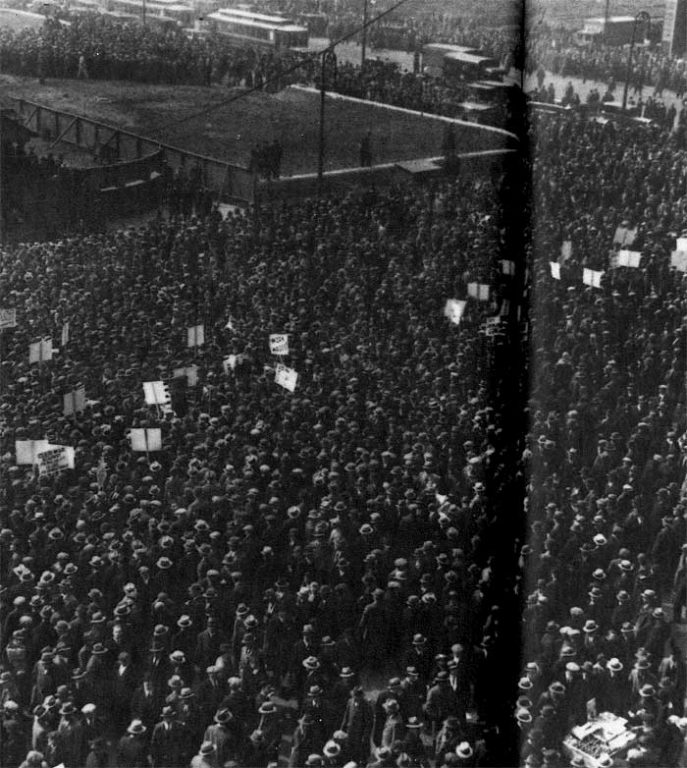

It was 1936, and there I was, Mary Johnsrud, marching down lower Broadway in a May Day parade, chanting at the crowds watching on the sidewalk: ‘FELLOW WORKERS, join our RANKS!’ Nobody, I think, joined us; they just watched. We were having fun; beside me marched a tall, fair young man, former correspondent of the Paris Herald, who looked like Fred MacMurray. His name was John Porter. Johnsrud was on the road with Maxwell Anderson’s Winterset, playing his Broadway role of the blind man. I had been out of college and married to him nearly three years.

Since 1 October 1933, Johnsrud, known as ‘John’, and I had been living in New York in a one-room apartment at Two Beekman Place, a new building opposite One Beekman Place, where Ailsa Mellon Bruce and Blanchette Hooker Rockefeller lived. Most months we could not pay the rent. It was a pretty apartment, painted apricot with white trim; it had casement windows and Venetian blinds (a new thing then), a kitchen with a good stove, a ‘breakfast alcove’, and a dressing room with bath besides a little front hall and the main room. Good closet space. Nice elevator boys and a doorman. Fortunately the man at Albert B. Ashforth, the building agent, had faith in John, and fortunately also the utilities were included in the rather high rent. The telephone company, being a ‘soulless corporation’, unlike dear Albert B. Ashforth, kept threatening to shut the phone off, but gas and electricity would keep on being supplied to us unless and until we were evicted.

If we were evicted and the furniture put out on the street (which did not happen in good neighbourhoods anyway), it would not be our own. We were living with my Miss Sandison’s sister’s furniture, Miss Sandison having been my Vassar Professor of English. We owned not a stick ourselves except a handsome card table with a cherry wood frame and legs and a blue suede top, which someone (probably Miss Sandison herself) had given us for a wedding present. When we moved into Beekman Place, the Howlands (Lois Sandison, who taught Latin at Chapin) let us have their Hepplewhite-style chairs and the springs and mattresses of their twin beds, which we had mounted on pegs that we painted bright red and which we set up in the shape of an ‘L’ with the heads together – you couldn’t have beds that looked like bedroom beds in a living room, as our one room was supposed to be. Instead of spreads, we had covers made of dark brown sateen (Nathalie Swann’s idea), and at the joint of the ‘L’, where our two heads converged, we put a small square carved oak table, Lois Sandison Howland’s, too, with a white Chinese crack table lamp that we had found at Macy’s.

On the walls we had Van Gogh’s red-lipped Postmaster (John’s guardian spirit) from the Hermitage, and Harry Sternberg’s drawing of John looking like Lenin. Then there were Elizabeth Bishop’s wedding present, bought in Paris – a coloured print, framed in white, rather surreal, called Geometry, by Jean Hugo, great-grandson of the author – and my Vassar friend Frani’s wedding present – a black-framed, seventeenth-century English broadside, on ‘The Earl of Essex Who cut his own Throat in the Tower’ – not Elizabeth’s Essex, brother to Penelope Devereux, but a later one, no longer of the Devereux family. Probably the apartment had built-in bookcases, which (already!) held the 1911 Britannica. I am sure of that because I wrote a fanciful piece (turned down by the New Yorker) called ‘FRA to GIB’. I don’t know where that Britannica, the first of its line in my life, came from or where it went to; maybe it was Mrs Howland’s. On the floor, I think, were two oriental rugs, hers, too, obviously. In two white cachepêts (Macy’s) we had English ivy trailing.

To reassure a reader wondering about our moral fibre and ignorant of those Depression years, I should say that Mr and Mrs Howland (I could never call them ‘Lois and ‘Harold’) kindly made us feel that we were doing them a service by ‘storing’ their things while they, to economize, lived at the National Arts Club on Gramercy Park, Mr Howland being out of a job. We had bought ourselves a tall, ‘modernistic’ Russel Wright cocktail-shaker made of aluminium with a wood top, a chromium hors d’oeuvres tray with glass dishes (using industrial materials was the idea), and six silver old-fashioned spoons with a simulated cherry at one end and the bottom of the spoon flat, for crushing sugar and Angostura; somewhere I still have these and people who come upon them always wonder what they are.

Communist Party May Day parade, New York, 1930

Late one morning, but before we had got the beds made, ‘Mrs Langdon Mitchell’ was announced over the house phone, and the widow of the famous (now forgotten) playwright sailed in to pay a formal call, which lasted precisely the ordained fifteen minutes although we were in our night clothes and she, white-haired, hatted and gloved, sat on a Hepplewhite chair facing our tumbled sheets. We must have met this old lady at one of Mrs Aldrich’s temperance lunches in the house on Riverside Drive, where the conversation was wont to hover over ‘dear Beatrice and Sidney (Webb)’ and Bis Meyer, my classmate, daughter of Eugene Meyer of the Federal Reserve Bank, was described as ‘a beautiful Eurasian’, a gracious way our hostess had found of saying Jewish. Mr Aldrich had been the music critic of the New York Times. John and I had gone up to Rokeyby, the Aldriches’ country house, for Maddie Aldrich’s wedding to Christopher Rand, a Yale classic major and an Emmet on his mother’s side whom Maddie had met, hunting, on weekends. At the wedding, Maddie’s cousin Chanler Chapman (A Bad Boy at a Good School, son of John Jay Chapman and model, in due course, for Bellow’s Henderson the Rain King) had spiked Mrs Aldrich’s awful grape juice ‘libation’ and got some of the ushers drunk. Now the couple had an all-blue apartment with a Judas peephole in the door, Chris had a job with Luce on Fortune, and Maddie had started a business called ‘Dog Walk’.

I think about the dances at Webster Hall, organized by the Communist Party. That was where I had met John Porter (I had better start calling him ‘Porter’, so as not to mix him up with ‘John’), who had been brought by Eunice Clark, the classmate who had edited the Vassar Miscellany News. Eunice was always trendy, and I guess we were all what was later called ‘swingers’; Webster Hall was an ‘in’ thing to do for Ivy League New Yorkers – a sort of downtown slumming; our uptown slumming was done at the Savoy Ballroom in Harlem, usually on Friday nights. Maybe real Communists steered clear of Webster Hall, just as ordinary black people did not go to the Savoy on those Friday nights when so many white people came.

I remember one Webster Hall evening – was it the Porter time? – when John and I had brought Alan Lauchheimer (Barth) with us and he found some classmates from Yale there, in particular one called Bill Mangold who would soon be doing PR for medical aid to the Spanish Loyalists – a Stalinist front – and with whom I would later have an affair. At Webster Hall, too, we met the very ‘in’ couple, Tony Williams, a gentleman gentlemen’s tailor (see ‘Dog Walk’ and the Don Budge-Wood laundry firm) who had married Peggy LeBoutiller (Best’s); they knew Eunice Clark and her husband, Selden Rodman, brother of Nancy Rodman, Dwight Macdonald’s wife.

Selden and Alfred Bingham (son of Senator Bingham of Connecticut) were editors of Common Sense, a Lafolletteish magazine they had started after Yale. ‘Alf’ was married to Sylvia Knox, whose brother Sam was married to Kay McLean from Vassar; both were trainees at Macy’s. At a party at the Knoxes’ I met Harold Loeb, the technocrat and former editor of Broom and a character in The Sun Abo Rises (related also to Loeb of Loeb and Leopold, murderers). Leaning back on a couch while talking to him about Technocracy and having had too much to drink, I lost my balance in the midst of a wild gesture and tipped over on to a sizzling steam radiator. As he did not have the presence of mind to pull me up, I bear the scars on the back of my neck to this day.

Before that, Selden, in black tie, had led a walk-out of diners in support of a waiters’ strike at the Waldorf, which Johnsrud and I joined, also in evening dress – Eunice was wearing a tiara. At another table Dorothy Parker and Alexander Woollcott and Heywood Broun got up to walk out, too. The Waldorf dicks chased Selden out of the Rose Room and into the basement, where they tried to beat him up. Then he was taken to be charged at the East 51st Street police station while some of us waited outside to pay his bail and bring him back home to Eunice. It was all in the papers the next day, though Johnsrud and I were too unknown to be in the story. The reader will find some of it, including Eunice’s tiara and a pair of long white kid gloves in, in chapters six and seven of The Group. It was the only time I saw Dorothy Parker close up, and I was disappointed by her dumpy appearance. Today television talk shows would have prepared me.

At Selden and Eunice’s apartment – in a watermelon-pink house on East 49th Street – in the course of a summer party in the little backyard, I met John Strachey, then in his Marxist phase (The Coming Struggle for Power) and married to Esther Murphy (Mark Cross, and sister of Gerald Murphy, the original of Dick Diver in Tender is the Night); I was shocked when he went to the toilet to pee – they were serving beer – and left the door open, continuing a conversation while he unbuttoned his fly and let go with a jet of urine. English manners? I wondered. Or was it the English left?

I was having class war problems with the New Republic. The pipe-smoking Malcolm Cowley – ‘Bunny’ (Edmund) Wilson’s successor as literary editor – though a faithful fellow traveller, was too taciturn usually to show his hand. After the first book he had given me to review, when I was still in college, he almost never gave me another but let me come week after week to the house on West 21st Street that was the New Republic’s office then – quite a ride for me on the Ninth Avenue El. Wednesday was Cowley’s ‘day’ for receiving reviewers; after a good hour spent eyeing each other in the reception room, one by one we mounted to Cowley’s office, where shelves of books for review were ranged behind the desk, and there again we waited while he wriggled his eyebrows and silently puffed at his pipe as though trying to make up his mind. Sometimes, perhaps to break the monotony, he would pass me on to his young assistant, Robert Cantwell, who had a little office down the hall. Cantwell was a Communist, a real member, I guess, but unlike Cowley, he was nice. He was fair and slight, with a somewhat rabbity appearance, and he, too, came from the Pacific Northwest, which gave us something to talk about. ‘Cantwell tells me the story of his life,’ I wrote to my friend Frani in December 1933. In 1931, he had published a novel, Laugh and Lie Down, and in 1934 he would publish a second, The Land of Plenty. Both were about Puget Sound and were described to me later by a Marxist critic as ‘Jamesian’ – he counted as the only proletarian novelist with a literary style. I had not read him then; nor had I read Cowley’s Blue Juniata or Exile’s Return, but with Cantwell that did not matter. After the New Republic, he went to work for Time and moved to the right, like Whittaker Chambers, who may well have been his friend. The other day someone wrote me that Lillian Hellman tried to stage a walk-out from Kenneth Fearing’s funeral service because Cantwell was one of the speakers. Can you imagine? Yes. Now he is dead himself. I should have liked to thank him for his interesting book, The Hidden Northwest, which led me to Washington Irving’s Astoria – a happy discovery. I learn from my 1978-79 Who’s Who (he was still living then) that he was named Robert Emmett Cantwell. A misnomer, typically northwestern, for Robert Emmet, the Irish patriot? A spelling error by Who’s Who? Or just no connection?

Cowley had another cohort, very different, by the name of Otis Ferguson, a real proletarian who had been a sailor in the Merchant Marine. ‘Oat’ was not in the book department; he wrote movie reviews. But he carried great weight with Cowley, though he may not have been a Marxist – he was more of a free-ranging literary bully without organizational ties. I had a queer time with him one evening when John and I went to look him up at his place on Cornelia Street, the deepest in the Village I had yet been. At our ring he came downstairs but, instead of asking us up to his place, he led us out to a bar for a drink, which seemed unfriendly, as he had given me his address and told me to drop by. I am not sure whether it was John or me that made him edgy or the pair of us – notre couple, as the French say. Perhaps he and John argued about films – John had worked in Hollywood, after all. Or could it have been simply that we had come down from Beekman Place? Anyway, whatever happened that evening and whatever caused it cannot have been the reason for my sudden fall from favour at the New Republic. No.

It was a book: I Went to Pit College, by Lauren Gilfillan, a Smith girl who had spent a year working in a coal mine – one of the years when I had been at Vassar. Cowley must have thought that here at last was a book I was qualified to review, by having had the contrary experience. The book was causing a stir, and Cowley, as he handed it over to me, benignly, let me understand that he was giving me my chance. I sensed a reservation on his part, as though he were cautioning me not to let the book down. He was allowing me plenty of space, to do a serious review, not another 300-word bit. And with my name, I dared hope, on the cover. I got the message: I was supposed to like the book. For the first time, and the last, I wrote to order. It would have been nice if I could have warmed to the task. But the best I could do was to try to see what people like Cowley saw in the book. With the result, of course, that I wrote a lifeless review, full of simulated praise. In short a cowardly review. Rereading it now, for the first time, in more than fifty years, I am amazed at how convincing I sound. In my last sentence I speak of a ‘terrific reality’.

But then came the blow. Cowley had second thoughts about the book. Whether the Party line had changed on it or for some other reason he now decided that it was overrated. I cannot remember whether he tried to get me to rewrite my review. I think he did but, if so, he was unsatisfied. In any case, he printed my laudatory piece and followed it with a correction. The correction was signed only with initials: O. C. F. ‘Oat’, of course. In fact it must have been he who changed Cowley’s mind. As a blue-collar reader, he had looked over the Smith girl’s book – or read my review of it – and responded with disgust. Which he expressed to Cowley. And, ‘Write that,’ said Cowley. Whereupon ‘Oat’ did. A 300-word snarl, merited or unmerited – who knows? I cannot really blame ‘Oat’ for the effect of those jeers on my feelings. Cowley would hardly have told him that he had virtually ordered a favourable review.

But had he? Trying to be fair to him, I asked myself now whether I could have misread the signals: could he have been telling me to pan the book? I do not think so. But either way the lack of openness was wrong. And it was a mean trick to play on a beginner; when my review came out, in May 1934, I was not yet twenty-two. I agree that a lot of the fault was mine: I should have written my real opinion, regardless of what he wanted. But abuse of power is worse than girlish weakness, and Cowley was a great abuser of power, as he proved over and over in his long ‘affair’ with Stalinism: for this, see under ‘Cowley’ in Letters on Literature and Politics by Edmund Wilson, edited by Elena Wilson. But it cannot have been all Stalinism; he must have taken a personal dislike to me. I leave it to the reader to decide between us.

For Selden Rodman at Common Sense, I had written a review (very favourable) of The Young Manhood of Studs Lonigan, the second volume of the Studs Lonigan trilogy. Farrell called or wrote to thank me. All we had in common was being Irish, middle-western, ex-Catholic and liking baseball (and I was only half midwestern and half Irish), but Farrell, gregarious and hospitable, took to me anyway, and when John was on the road with Winterset, I went to gatherings at his place, though I felt like a complete outsider. Farrell was married to or lived with an actress (Hortense Alden; I had seen her in Grand Hotel), but there was nobody from the theatre at those evenings. Now, half a century later, I know that she had had an affair with Clifford Odets and I wonder what Farrell made of that, which may have happened before his time.

In the apartment Farrell and Hortense shared on Lexington Avenue, the guests were all intellectuals, of a kind unfamiliar to me. I could hardly understand them as they ranted and shouted at each other. What I was witnessing was the break-up of the Party’s virtual monopoly on the thought of the left. Among the writers who had been converted to Marxism by the Depression, Farrell was one of the first to free himself. The thing that was happening in that room, around the drinks table, was important and eventful. An orthodoxy was cracking, like ice floes on the Volga. But I was not in a position to grasp this, being still, so to speak, pre-Stalinist in my politics, while the intellectuals I heard debating were on the verge of post-Stalinism – a dangerous slope. Out of the shouting and the general blur, only two figures emerge: Rahv and Phillips. Farrell made a point of introducing them, and I knew who they were – the editors of Partisan Review. As the popular song said, my future just passed.

It was odd, actually, that I knew of the magazine; it must have had a very small circulation. But a couple who ran a stationery store on First Avenue, around the corner from our apartment, had recommended it to me, knowing that I wrote for the Nation. They were Party members, surely – of the type of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, though the wife was much prettier than Ethel. And Partisan Review was a Party publication, the organ of the John Reed Club. But I had no inkling of that then; skill in recognizing Communists came to me much later. When the pair of stationers showed me an early issue of the magazine, the husband running from behind the counter to fetch it, the wife proudly watching as I turned the pages, I found that it was over my head. It was devoted to an onslaught on the American Humanists – Stuart Sherman and Paul Elmer More – with a few rancorous side swipes at the Southern Agrarians – Tate and Ransom, the group called the Fugitive Poets. I do not remember any fiction or poetry, only long, densely written articles in a language that might as well have been Russian. I was distantly familiar with the Humanists, having read about them in the Bookman, but these Agrarians were a mystery to me, and PR’s crushing brief against them left me bewildered. As for the dreary Humanists, I was surprised that they needed so much attacking. In fact Rahv and Phillips and their colleagues were beating a dead horse there.

Nevertheless, to please the stationers, with whom we were friendly, I kept buying the magazine and trying my best to read it. There is a sad little sequel to my introduction to Partisan Review. It ceased publication when the Party cut off funds from the John Reed Clubs (it was announced that they would be replaced by an American Writers Congress); this may have already happened when I met the editors at Farrell’s. And when Partisan Review resumed, still edited by Rahv and Phillips but without Jack Conroy et al on the mast-head, it had changed colour. Dwight Macdonald and Fred Dupee and I and George L. K. Morris, our backer, were on the new editorial board, and PR was now anti-Stalinist. Some time later, maybe when my first book was published, out of the blue came a shrill letter, many times forwarded, from the Mitchell Stationers accusing me of running out on a bill John and I owed them. I cannot remember what I did about it, if anything.

In our Beekman Place apartment, besides Partisan Review, I was trying to read Ulysses. John in the breakfast nook was typing his play University (about his father and never produced), and I was writing book reviews. Every year I started Ulysses, but I could not get beyond the first chapter – ‘stately, plump Buck Mulligan’ – page forty-seven, I think it was. Then one day, long after, in a different apartment, with a different man (which?), I found myself on page forty-eight and never looked back. This happened with many of us: Ulysses gradually – tout with an effect of suddenness – became accessible. It was because in the interim we had been reading diluted Joyce in writers like Faulkner and so had got used to his ways, at second remove. During the modernist crisis this was happening in all the arts; imitators and borrowers taught the ‘reading’ of an artist at first thought to be beyond the public power of comprehension. In the visual arts, techniques of mass reproduction – imitation on a wide scale – had the same function. Thanks to reproduction, the public got used to faces with two noses or an eye in the middle of the forehead, just as a bit earlier the ‘funny’ colours of the Fauves stopped looking funny except to a few.

When the first Moscow trial took place and Zinoviev and Kamenev were executed in August 1936 (and the Spanish Civil War began), I did not know about it, as I was in Reno. Shortly after that May Day parade, I had told John, who was back from playing Winterset on the road. I said I was in love with John Porter and wanted to marry him. This was in Central Park while we watched some ducks swimming, as described in ‘Cruel and Barbarous Treatment’. Except for that detail, there is not much resemblance between the reality and the story I wrote two years later – the first I ever published. When I wrote that story (which became the opening chapter of The Company She Keeps), I was trying, I think, to give some form to what had happened between John, John Porter and me, in other words, to explain it to myself. But I do not see that I was really like the nameless heroine, and the two men are shadows, deliberately so. I know for a fact that when I wrote that piece I was feeling the effects of reading a lot of Henry James, yet today I cannot find James there either – no more than the living triangle of John, John Porter and me.

John Porter was tall, weak, good-looking, a good dancer; his favourite writer was Remy de Gourmont, and he had an allergy to eggs in any form. He went to Williams (I still have his Psi U pin) and was the only son of elderly parents. When I met him, he had been out of work for some time and lived by collecting rents on Brooklyn and Harlem real estate for his mother; the family, degentrifying, occupied the last ‘white’ house in Harlem, on East 122nd Street, and owned the beautiful old silver communion cup from Trinity Church in Brooklyn; it must have been given to an ancestor as the last vestryman. After the Paris Herald and Agence Havas, John had worked in Sweden for the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, but since then had been unable to connect with a job. Collecting rents on the wretched tenements still owned by his parents was his sole recourse, and most of the poor blacks who lived in them dodged him as best they could, having no earnings either. The Porters were very close with the little they had; they neither drank nor smoked and disapproved of anybody who did. The old father, who had once been an assemblyman in Albany, was deaf and inattentive, and John hid his real life from his mother.

He was in love with me or thought he was; my energy must have made an appeal to him – he probably hoped it would be catching. Despite his unemployment, dour mother, rent-collecting, he was gay and full of charm. He was fond of making love and giving pleasure. By the time John came back from the road, Porter and I had a future planned. Together with a journalist friend who had a car, he was going to write a travel book on Mexico. Mexico was very much ‘in’ then among sophisticated people, especially as Europe, what with Hitler and the fall of the dollar, was looking more and more forbidding. Hence John and his co-author had readily found a publisher to advance $500 on a book contract with royalties.

It may be that Porter already had the idea of the Mexican book at the time he met me and merely needed the thought of marriage to spur him on. In any case, I fitted into the picture. After Reno, where my grandfather was getting me the best law firm to file for divorce, Porter would wait while I visited my grandparents in Seattle, and then the three of us would start out from New York in the friend’s small car. It would be an adventure.

And Johnsrud? He took it hard, much harder than I had been prepared for. I felt badly for him; in fact I was torn. The worst was that, when it came down to it, I did not know why I was leaving him. I still had love of some sort left for him, and seeing him suffer made me know it. Out of our quarrelling, we had invented an evil, spooky character called ‘Hohnsrud’ (from a misaddressed package) who accounted for whatever went wrong. Our relations in bed, on my side, were unsatisfactory, and infidelity had shown me that with other men that was not so. It was as though something about John, our history together, made me impotent, if that can be said of women. I had no trouble even with an earnest little actor in Adler elevated shoes. Yet I doubt that sex was really the force that was propelling me; had we stayed together I might well have outgrown whatever the inhibition was. I was still immensely impressed by him and considered myself his inferior. Hence it stupefied me, shortly after our break-up, to hear Frani say, by way of explanation: ‘Well, your being so brilliant must have been difficult for him!’

It is a mystery. No psychoanalyst ever offered a clue, except to tell me that I felt compelled to leave the men I loved because my parents had left me. Possibly. What I sensed myself was inexorability, the moirae at work, independently of my will, of my likes or dislikes. A sweet, light-hearted love affair, all laughter and blown kisses, like Porter himself, had turned leaden with pointless consequence. Looking back, I am sorry for poor Porter, that he had to be the instrument fated to separate me from John. And for him it was a doom, which took him in charge, like the young Oedipus meeting the stranger, Laius, at the crossroads; I wonder whether he may not have felt it himself as he finally set out for Mexico, where he would die of a fever after over-staying his visa and going to jail. All alone in a stable or primitive guest quarter belonging to a woman who had been keeping him and then got tired of it.

Meanwhile, though, before I left for Reno, Porter and I went out for a few days to Watermill, Long Island, where his parents still owned a mouldy summer bungalow in the tall grass high up over the sea. With us was a little Communist organizer by the name of Sam Craig. I have told the story of that in the piece called ‘My Confession’ in On the Contrary. The gist of it is that the Party was sending him to California in a car some sympathizer had donated. But Sam did not know how to drive. So he had asked Porter, a longtime friend, to take the car and give him driving lessons on the lonely back roads around Watermill. Sam was a slow learner, to the point of tempting us to despair for him. On the beach, all that week the red danger flags of the Coast Guard were out, and we swam only once in the rough water. In the evenings, over drinks in the mouldy old house lit by oil lamps, Sam was trying to convert me to communism. To my many criticisms of the Party, he had a single answer: I should join the Party and work from the inside to reform it. This was a variant on ‘boring from within’, the new tactic that corresponded with the new line; the expression seems to have been first used in 1936. Evidently Sam was thinking of termite work to be done on the Party itself, rather than on some capitalist institution. Very original on his part, and he nearly convinced me.

In the end, I said I would think it over. Sam passed his driving test and went off by himself in the car, heading west. As I wrote in ‘My Confession’, I ask myself now whether this wasn’t the old car that figured in the Hiss case – the car Alger gave to the Party. I never learned what happened to Sam. He may have perished in the desert or gone to work recruiting among the Okies or on the waterfront. And here is the eerie thing about the Porter chain of events: everyone concerned with him disappeared. First, Sam; next the man named Weston, Porter’s collaborator on the Mexican guidebook, who vanished from their hotel room in Washington after drinks one night at the National Press Club, leaving his typewriter and all his effects behind.

Porter searched for a week, enlisting police help; they canvased the Potomac, the jails, the docks, the hospitals, talked to those who had last seen him. The best conclusion was that he had been shanghaied. By a Soviet vessel? Or that he had had some reason to want to disappear. But without his typewriter? A journalist does not do that. He was never found.

Meanwhile I, too, had dropped out of the picture. I was in New York, at the Lafayette Hotel and concurring by telephone with the decision Porter came to: to go on to Mexico without Weston and get the book started, while he still had the car and half the advance. Of course I had qualms. Even though he had taken it with good grace when, on my return from Reno and Seattle, I had got cold feet about the Mexican trip. I forget what reason I gave. The fact was, I had lost my feeling for him. But I let him think I might join him once he had ‘prepared the way.’ From Washington he wrote or telephoned every day; after he left, I wrote, too, day after day, addressing my letters to Laredo, general delivery. I never heard from him again.

Late that fall, a crude-looking package from an unknown sender arrived in the little apartment I had taken on Gay Street in the Village. Having joined the Committee for the Defense of Leon Trotsky, whose members were getting a certain number of anonymous phone calls – Sidney Hook, we heard, looked under the bed every night before retiring – I was afraid to open the thing. As far as I could make out from the scrawled handwriting, it came from Laredo, on the Mexican border; conceivably there was a connection with Trotsky and his murderous enemies in Coyoacan. I am ashamed to say that I asked Johnsrud if he would come over and be with me while I opened it. He did – first we listened, to be sure we could not hear anything ticking – but inside all we found was a quite hideous pony-skin throw lined with the cheapest, sleaziest sky-blue rayon, totally unlike Porter, who had a gift for present-giving. I had already ruled out any likelihood that the crudely wrapped package had anything to do with him, even though Laredo had been on his way. The sleazy throw confirmed this. On Johnsrud’s advice probably, I wrote or wired the sender. In reply, I got a telegram: ‘package comes from john porter mexico.’

That was all. At some point that autumn his mother wrote me, demanding that I pay her for the telephone calls he made to me in Seattle. I refused. Next, his parents wanted to know, perhaps through a third party, whether I had heard from him at Christmas – they had not. But my memory here is hazy. And I cannot remember when I finally learned of his death. It was more than a year later, and it seems to me that it came to me in two different versions, from different sources. Certainly the second was from Marshall Best, a Viking Press editor who lived at Two Beekman Place and served special meatballs baked in salt. He was a devoted friend of Porter’s and, if I may say it, quite a devoted Stalinist sympathizer. By now, naturally, with the Trotsky Defense Committee, he disliked me on political grounds. It may have given him some satisfaction to tell me a piece of news that was not only painful but reflected poorly on me. As though I were the principal cause of Porter’s death. And perhaps, in truth, I was. His mother must have thought so.

If it had not been for me, he would never have been in Mexico. He would still be collecting rents for his parents. And, if I had gone along with him, instead of copping out, I would never have let him overstay his visa, which had caused him to land in prison, which caused him to contract diphtheria or typhus or whatever it was that killed him when, on his release, the woman he had been living with let him come back and stay in her stables.

Well. As an English writer said to me, quoting Orwell, an autobiography that does not tell something bad about the author cannot be any good.

I am not sure why I lost my feeling for Porter. At the time I thought it was his letters – wet, stereotyped, sentimental – that had killed my love. The deflation was already beginning, obviously, when I met the man in the Brooks Brothers shirt on the train that was taking me west. The letters and phone calls completed the process. Whatever it was, I now realize that I positively disliked that Fred MacMurray look-alike when I saw him gazing fondly down at me when he met me on my return. The distaste was physical as well as intellectual. I could not stand him. He had become an embarrassment, having served his purpose, which I suppose was to dissolve my marriage. I was appalled, for him and for myself.

Did he notice that I had changed? Nothing was ever said, and I tried to hide it. ‘Succès?’ ‘Succès fou!’ had been our magic formula after love-making, and ‘Succès fou!’ I went on duly repeating, I imagine. I was telling myself that it was only a few days; in a few days he would have left. Such cowardice was very bad of me. If I had had the courage to tell him, he might not have started out without me. Yet I am not sure. Would my having ‘the heart’ to tell him have made the difference? Probably the truth was that Porter had to go to Mexico; his bridges were burned. That applied to all three of us. Nothing could return to the status quo ante. John and I had left Two Beekman Place behind, to the tender mercies of Albert B. Ashforth, who painted our pretty apricot walls another colour, I suppose. The Howlands’ furniture had been passed on to a friend of Alan Barth’s named Lois Brown. A trunk with my letters and papers in it went to storage, never to be reclaimed. Johnsrud had moved to the Village. While waiting for my grandfather to fix things up with Thatcher & Woodburn in Reno, I had stayed with Nathalie Swan in her parents’ Georgian house in the East 80s. No, nothing could go back to what it had been. Old Clara, my Harlem maid, returned to her funeral parlour business – she was proud of having buried a fighter named Tiger Rowers. I never ate her smothered chicken again. Poor ‘Hohnsrud’ of course had died.

Moreover, Porter was sensitive – think of his allergies. He must have heard the difference on the telephone while I was still in Seattle; I am a fairly transparent person. And if he guessed my changed feelings, he kept it strictly to himself. The question I should ask myself is not did he know but how soon did he know? It is a rather shaking thought.

Photograph © Popperfoto