I was possessed, for a year, by a woman whose name I do not know.

What is a name? Sometimes I am startled when someone says to me, Rebecca.

I think, who is that?

Then, ah! yes! me.

When I wrote stories as a kid, I approached naming with frustration. I could think of names: my brothers’, my friends’, my teachers’. But they were my brothers, my friends, my teachers. If I named characters after them, they would be them. So I devised new names: Mr Beezlewop, Meggles Fishson. They looked silly on the page, but at least they were individual. No one could say they were anyone other than themselves.

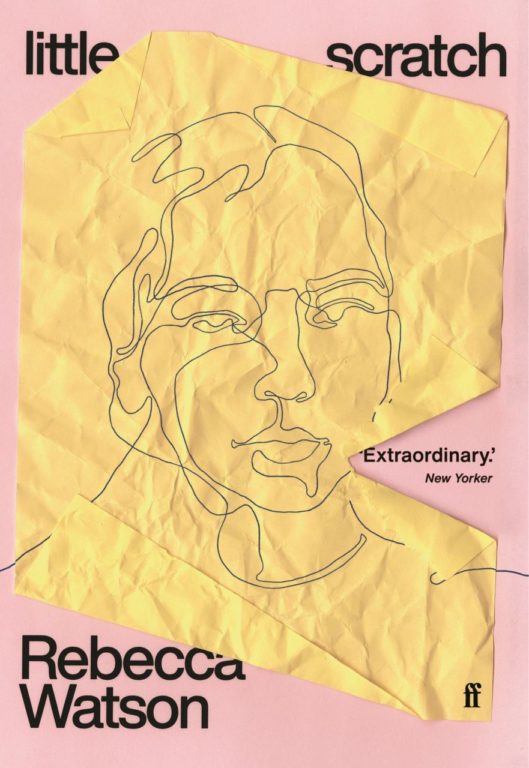

I don’t have a habit of retaining my primary school habits. But when I came to write little scratch, my debut novel (the woman inside my head loud) I still resisted naming. There were too many reasons not to: my protagonist was an everywoman, she was forcefully anonymous, separate, alone. She was only performing for herself, where identity is immediate rather than introduced. The reader, who is immersed inside her head, taking on her thoughts as their own, should not feel roped off by a different name. I resisted. And the resistance felt age-old, little me with my purple notepad rising up and insisting, no, don’t name her. That wouldn’t be right.

I’m quite firm in stating that little scratch is fiction. Not autofiction, not an autobiographical novel, not a novel inspired by true events, not memoir, not hybrid-something: it’s a novel. At times I think I am too firm, too harsh. Ears twitching ready to say, Excuse me? No.

I know the assumptions often made of debut novels and fiction by women. But it would be understandable that someone might assume. little scratch is set in a world very similar to mine. (Excuse me? No.)

I like to call it a tightrope, but even that isn’t right. I’m not teetering, desperate not to fall off; to slip back into my life. I say that to explain it to others. Fiction is a tightrope. We all sometimes slip.

But it’s not a slip. I lean my foot off, touch the ground. Then I get back up.

Yesterday, I nearly said a line out loud that came to me as I looked at something I passed. But then I thought, no, I’ll keep that. If I say it out loud, it will be attached to me. It can no longer be a character’s. It was only a simile, not a feeling, not anything, really. But speaking would fix it in my voice.

It wasn’t actually yesterday. I am tweaking fact. Weeks ago, I nearly said a line out loud that had come to me as I looked at something I passed. But then I thought, no, I’ll keep that. I stopped myself. A lot of times I don’t. I say the line. I let it be lost to the moment. It’s best not to bow to fiction too much. Otherwise next time it’ll expect more of me.

I wrote something before little scratch in which I borrowed from my memories. It was meant to be me, it was what at the time I called creative non-fiction. I was using fiction’s tools with my own life. It was a way of working out my voice, of how to write. Whenever a distant memory rose in my head I would note it down, and later, I would write it. They were memories that often rose, that my unconscious had not finished with, that needed wrestling, needed conclusion, before they could submerge further.

So I wrote them. And now they never come back. I reread the book recently and I resented them on the page. I had forgotten them, and they felt, sitting there, like sacrifices.

No, little scratch is fiction. I am hesitant, now, to write in any other way.

I remember the writing like a rush. Instinct came from somewhere; it was nice to have something to trust. I would write quickly, by hand, and a system arrived across the page. There was something to follow. Someone to follow.

I was possessed for a year by a woman whose name I did not even know.

She was so loud in my head that sometimes I would wonder, is this me? Excuse me, no.

How many people is a person in one day? Reliability, likeability, linearity: these can be expected from fiction. But how reflective is that of experience? I was interested in the many selves a person inhabits within a day. I wanted to include the thoughts that appear unbidden, the convictions that might undo. I wanted to take on these conflicts and multiplicities. I did not want my protagonist to be the authority on herself. How well do we really know other people, yes, but how well do we even know ourselves?

I have three sheets of paper under the bed on which I have written my notes on craft. Before an interview or event, I lay them out on the table and remind myself of what I once thought.

A friend tells me, I wish I had rehearsed my lines before the publicity for my book began.

In an interview, a writer tells me that sometimes she sits at her desk and says to herself, sternly, Oh you know how to write a novel! Something inside you knows. So you just keep your head down, do what you’re doing, subject verb object, off you go.

I have a similar mantra. Let’s fucking go, let’s do this. Just write anything down, get moving. I type, or take the lid off my pen, and once I have started, something happens.

Something happens. How helpful is that?

But it is. I trust. Let’s fucking go, let’s do this. Just write anything, get moving. Off you go.

Rebecca Watson’s little scratch is available now.