Eyal Weizman in conversation with Rana Dasgupta

rana dasgupta: I’d like to begin by talking about the shape of the border, which conventionally appears as a line.

Because of its particular conception of threat – external and internal – Israel has made a disproportionate contribution to state theories of defence and segregation. In Hollow Land (2007), your account of the military, bureaucratic and architectural systems with which the Israeli state organises territories and peoples, you identify a remarkable moment in its evolving conception of ‘border’. You describe the debate surrounding the Bar Lev Line: a chain of fortifications constructed by Israel along the Suez Canal after the 1967 Arab–Israeli War. The Bar Lev Line was supposed to be impregnable, but during the Yom Kippur War of 1973 it was breached in two hours by the Egyptian army.

This defensive disaster enhanced the influence of Ariel Sharon, principal critic of the Bar Lev Line, who had dismissed it as the Israeli ‘Maginot Line’ – referring to the vast defensive barrier built by France in the 1930s to protect against German invasion. Sharon argued that the border should be thought of not as a line but as a network extending deep into Israeli territory. You summarise his reasoning thus:

If the principle of linear defence is to prohibit (or inhibit) the enemy from gaining a foothold beyond it, when the line is breached at a single location – much like a leaking bucket of water – it is rendered useless. A network defence, on the other hand, is flexible. If one or more of its strongpoints is attacked and captured, the system can adapt itself by forming new connections across its depth.

eyal weizman: It is fair to say that there has never been an agreed-upon boundary to Israel and its territorial ambitions.

When the Zionist leadership accepted the territories marked out for Israel under the UN Partition Plan in 1947, they expected the borders to change during the anticipated Arab–Israeli War, which was already in preparation. Even after the war, and the expulsion of the Palestinians from Israel’s territorial acquisitions, Israeli historians have reported that the prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, accepted the ceasefire agreement because he imagined the borders would be further extended during the next round of conflict.

Still today, the question of borders has not been resolved. There is no consensus within Israel about whether a Palestinian state should exist – even in the most minimal of ways – and so there can be no agreement about Israel’s eastern border. Instead, there is the contested frontier along the West Bank governed by military forces, a compliant Palestinian authority and settler groups that dictate the political agenda.

In the absence of any hard or durable state boundary, smaller manifestations of borders, or border devices, have sprung up everywhere. Like worms cut into pieces, each taking on renewed life, fragments of the border exist deep within the space under Israeli control. In the West Bank, we see this represented by the fences around settlements and military bases, and by important infrastructure such as roads and bridges that function as methods of segregation. And we see it, of course, in the wall itself, which twists through Palestinian lands.

In Gaza, the wall has a different function. It not only cuts the territory off from the rest of Palestine but, by controlling land and maritime borders of the Gaza envelope, Israel is also able to regulate the quantities of all resources entering the territory: electricity, food, medicine, petrol, building materials and so on. With the ability to starve Gaza of resources, Israel ensures the Strip’s total dependency.

It is in this context that we need to see the so-called ‘Trump Plan’, which would create a Palestinian state by connecting fragments of land around Palestinian towns and cities through a network of raised highways, tunnels and bridges. The result would be two mutually exclusive geographies superimposed over the same land. This amounts to the vertical partitioning of Palestine, with Israelis travelling by bridge over Palestinian areas, owning the water underneath and controlling the airspace above – something I have called a ‘politics of verticality’.

There are many borders, and each one produces a different kind of territorial scenario and governing apparatus. The absence of a single line around the state has meant that the border is everywhere. And it goes beyond the organisation of physical space. The border provides a structure to state institutions and bureaucracies based on permits and the control of circulation – who can enter where and when.

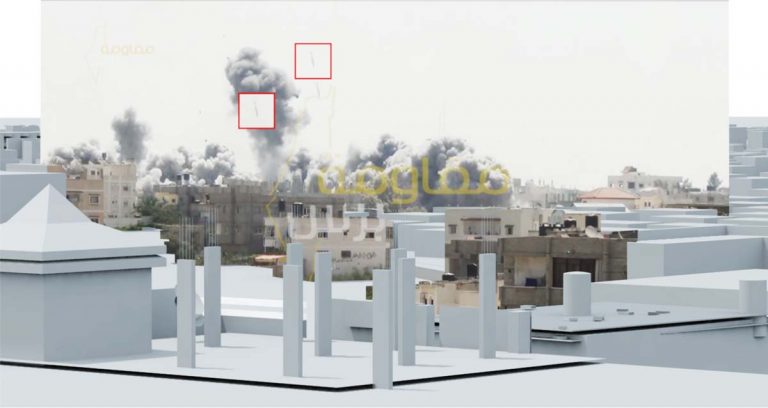

In July 2015, Forensic Architecture completed an investigation into the bombing of Rafah, Gaza, on 1 August 2014. Denied entry into the Gaza strip, Amnesty International and Forensic Architecture relied on thousands of images and videos shared online, or sent to them directly by citizens and journalists.

Above, Forensic Architecture located photographs and videos within a 3D model to tell the story of one of the heaviest days of bombardment in the 2014 Israel-Gaza war. ‘The Image-Complex’, Rafah, Gaza. © forensic architecture, 2015

Video still showing two bombs in mid-air fractions of a second before impact in the Al Tannur neighbourhood in Rafah, Gaza, on 1 August 2014. © forensic architecture, 2015

dasgupta: What does it mean for a border to exist within a bureaucracy?

weizman: Let’s say you’re a Palestinian in the West Bank. The wall that runs through the territory requires you to conform to a regime of permits that controls every aspect of your movement. You need a permit to pass through the checkpoints, and in order to obtain it you will need to do various things, including, sometimes, collaborating with the security forces. There are different kinds of permits, allowing movement at different times, for different durations and to different places in Israel, so that your movement in space is continuously and transparently monitored. In order to enforce this permit regime, the state must maintain constant individual surveillance, optical and technical.

The concrete and razor wire of the West Bank wall are reinforced with highly effective electronic sensors, a form of smart-fencing technology at which Israel excels. Border control has become one of Israel’s most important export industries. But we need to think of the border not only as a physical instrument but also as an optical-bureaucratic apparatus.

dasgupta: What has changed since you wrote Hollow Land?

weizman: The most important change since the early 2000s is the advent of digital surveillance. Surveillance complements the physical apparatus of the border rather than replacing it. Surveillance has moved into licence-plate and facial recognition, social networks and digital communication. Civil society and human rights activists in Palestine are monitored through their WhatsApp messages. An Israeli company called NSO Group Technologies is at the forefront of cyber surveillance and it has been reported that its product, Pegasus spyware, now aids repressive regimes worldwide. People are being arrested for what they post on Facebook. So again, we are talking about a system that is both physical and digital, and the intricacies of the relationship between the physical and the digital have very much become manifest since Hollow Land was written.

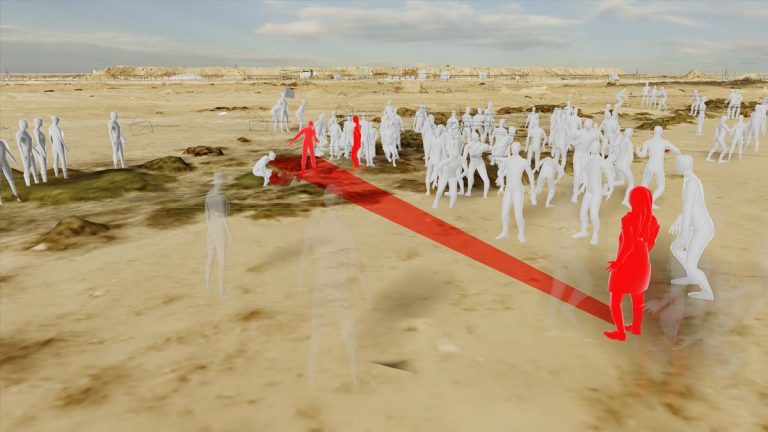

Forensic Architecture has investigated the use of live ammunition by Israeli security forces in 2018 protests in Gaza. On 1 June 2018, a shot fired into a group of Palestinian protestors near the village of Khuzaa killed twenty-one-year-old volunteer medic Rouzan al-Najjar and injured two others. Above, Forensic Architecture’s model captures the moment after the fatal shot is fired. © forensic architecture, 2019

From the positions of the three medics, who were struck by the same bullet, a ‘cone of fire’ can be estimated, from within which the bullet must have travelled. © forensic architecture, 2019

dasgupta: For several regimes across the world, Israel provides a kind of security gold standard. To what extent are its techniques copied and exported elsewhere?

weizman: It follows a circular movement. Israel has had very good European tutors when it comes to colonial technologies of domination. The logic of surveillance, segregation and separation is colonial in nature; it also existed in Palestine under British Mandate between the First and Second World Wars, before the Israeli state was formed. This same approach was applied in apartheid South Africa, where borders of every kind were, once again, used as instruments of population control.

Israel has operated under this logic for so long that it has developed many technologies of surveillance and physical domination, which, in turn, have been adopted by like-minded governments such as India (in particular along its frontier with Pakistan) and the US.

Europe is now at the forefront of this border frenzy. One thousand kilometres of security wall have been built in Europe since the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, some by agencies like Frontex – the European Border and Coast Guard Agency – with the specific intention of controlling migration. Walls and fences are only the most visible part of the system. Surveillance and control throughout the depth of the territory are crucial corollaries. For example, I think that the political contradictions imposed by Brexit on the new Irish border will make it an important test case for how borders of the twenty-first and twenty-second centuries will operate.

dasgupta: What is the justification for such a system in Europe?

weizman: In the early 2000s, of course, it was the ‘war on terror’. Post-9/11, the fear of ‘terror’ accustomed populations to the idea that state surveillance is benign, or that it is designed to serve their security and safety. I cannot overemphasise the psychological impact of this ambient terror on a population – and I don’t mean just the actions of terror groups but also the way that those actions were amplified in the public domain by governments and the media.

But this security-based rationale has since morphed into a rationale focused on anti-migration, which is now prevalent throughout Europe. It has been the basis for an extremely invasive surveillance regime, which attempts to control the movements of both people arriving in Europe and those already there. Migrants are tracked from when they cross the Sahara into northern Africa; their movements are tracked across the Mediterranean and at the borders of Europe, and every attempt is made to exhaust them, even kill them – through the European Union’s proxy African armies in Mali, Cameroon or Libya – in order to stop them from ever arriving. All of this is with the understanding that Europe’s most effective southern border is a body of water rather than a wall, a weaponised Mediterranean and its lethal waves in winter and spring, so that people are kept out even if it means killing them by not rescuing them, by scaling back rescue operations and criminalising the NGOs engaged in rescue procedures.

The line goes: the European public – at least its recognised citizens – has no reason to be scared of surveillance because it has nothing to hide, and so we can allow the state into our homes, our devices and our communications. Accepting this idea, we have dropped our guard.

Gradually, it has been not the state but the tech giants that have filled this gap. Now, the new corporate surveillance machine monitors everyone more or less continuously, and for other reasons. Your location in space, your spending habits, the people you meet and the things you do are registered. In East Germany, the Stasi had to enter your house while you were out at work and put bugs in your phones and walls. Today, we willingly buy and carry our own surveillance devices. We have put the bugs on ourselves.

In a sense, individual surveillance on the scale of an entire population fulfils certain functions of the border, in particular registration and tracking. One of the most important challenges of the twenty-first century, in fact, is this: how to navigate the complete erosion of the private domain. Our willing destruction of this domain allows for a new form of domination on an unprecedented global scale.

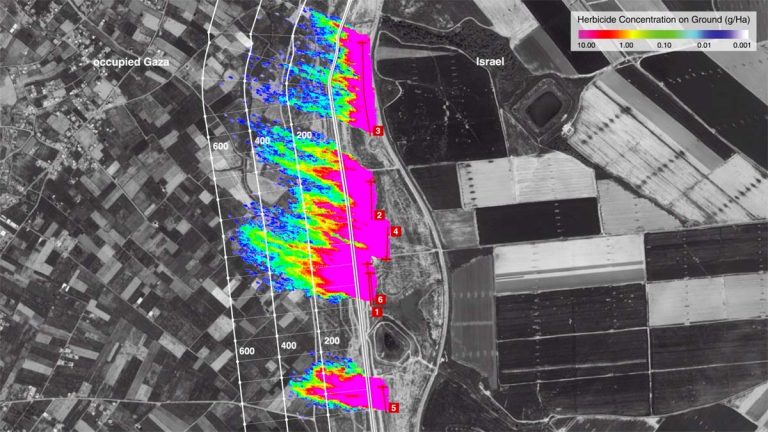

In July 2019, Forensic Architecture published an investigation into the unannounced aerial spraying of crop-killing herbicides along the eastern border of Gaza, a practice that has continued since 2014, destroying crops and farmlands hundreds of metres deep into Palestinian territory.

Above, Forensic Architecture’s analysis shows the distribution of herbicide as it travels westward into Gaza. © forensic architecture and dr salvador navarro-martinez, 2019

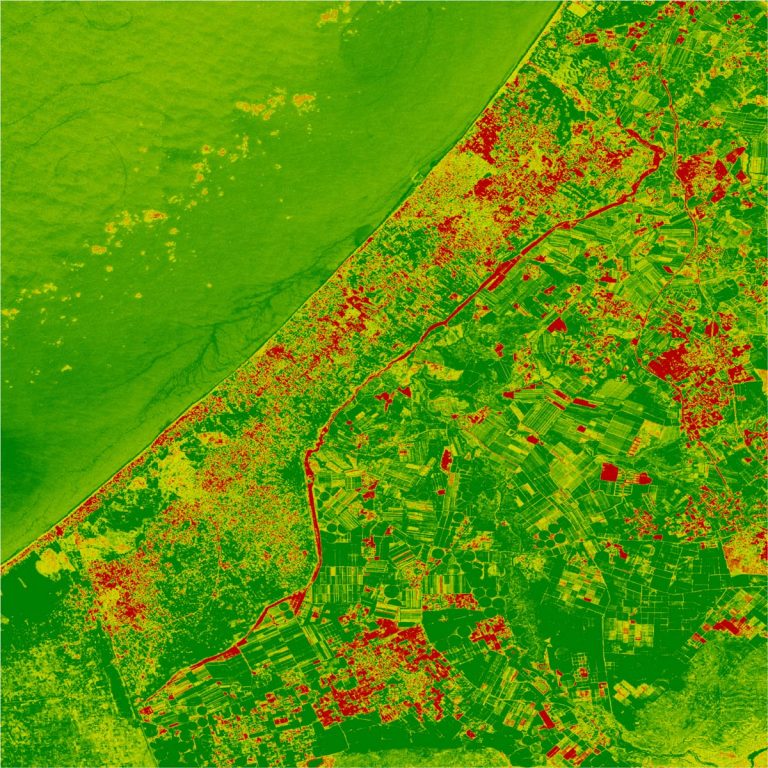

Map displaying long-term changes to vegetation health across the Gaza region over the past three decades of Israeli occupation. Red indicates areas in which vegetation was completely eradicated. © corey scher, 2019

dasgupta: In an older Europe, all the anxiety was concentrated at the borderline itself. Crossing from France to Germany, you showed your papers, you looked at the immigration official, you hoped there was nothing wrong. Then he let you pass and the anxiety was dissipated: you were on the other side and there were no further inspections. But you are describing a situation where the border is everywhere, and that moment of inspection is therefore constant. We are always trying to read the expression of that immigration official. Are we therefore always anxious?

weizman: A ‘classical’ border set-up like that would be based on the assumption that the ‘enemy’ is always outside. Today’s system is based on the belief that the enemy – whether that is a migrant, a terrorist, a social movement or group of protesters – is already inside.

Surveillance exists not only at the borders but everywhere, which might make us continuously anxious, but we have become anaesthetised to it. Because when something is everywhere, you stop feeling it. And the only solution would be collective political action. Individually we can try to camouflage ourselves – encrypt our messages, drop out of social media – but only collective action could truly confront the physical-digital regime of the everywhere-border. First, though, we would have to acknowledge that this is our reality. And it’s uncomfortable to acknowledge that you live in a permanent state of anxiety.

In April 2017, a former officer of the Israeli army, and member of Breaking the Silence, testified to gravely assaulting a Palestinian man in the occupied city of Hebron. The Israeli government closed the case claiming the officer had lied. Forensic Architecture launched their own independent investigation, published in February 2020. © forensic architecture / breaking the silence, 2020

Above, Forensic Architecture has used photogrammetry to create a point cloud scan of Shalala Street in occupied Hebron, Palestine.

Superimposed models based on the testimony of Palestinian and Israeli witnesses. © forensic architecture / breaking the silence, 2020

Superimposed models from the testimony of three witnesses at a militarised checkpoint in Hebron. © forensic architecture / breaking the silence, 2020

dasgupta: In recent years, your work has taken a very different turn. You are now involved with what you call ‘forensic architecture’, where the surfaces of buildings are taken as repositories of material evidence, especially of state-perpetrated atrocities. You have developed a sophisticated set of tools for gathering and reading this evidence, and thereby reconstructing the details of certain key events. For instance, in this era of drone warfare, which often occurs in remote places and kills all witnesses, leaving no one to contradict the bomber’s version of events, the ability to read the evidence of stone and glass can be decisive. Forensic Architecture, the group you set up in 2010, has used such capabilities to reconstruct atrocities in places as far-flung as Serbia, Syria, Palestine, Guatemala, China and the UK.

Your book Forensic Architecture (2017) begins with a very public precursor to this work. A 2000 libel case in the UK turned on the issue of Holocaust denial and therefore the veracity – or not – of the claim that German camps were used for systematic extermination by poison gas. This led to detailed debates both about the architecture of Auschwitz-Birkenau – whether, for instance, there were holes in the roof of the main chamber, without which it would not have been possible to introduce the gas canisters – and about the nature of the physical plans and satellite photographs which were often the only remaining evidence of this architecture available to us Forensic architecture is particularly useful in helping prove the crimes of governments, which are often not subject to the same scrutiny as their populations. You describe two kinds of crimes in particular: crimes of space and crimes in space. What are these?

weizman: First, we have crimes of space. Crimes of space-making. Architecture can be employed as a form of violence and violation. This idea came from my research into the responsibility of Israeli architects and planners for the crimes of the occupation. Their crimes were committed on drawing boards. They drew lines that were built into concrete and eventually became instruments of control and segregation of Palestinian communities.

All governments use such techniques, but when you look at urban environments such as London, the methods are more subtle. Recent events in Hong Kong have shown just how effectively ‘smart-city’ infrastructure – licence-plate and facial recognition in the public domain – can be turned against social movements, protesters and civil society. As Francesco Sebregondi has shown, the bright idea of the smart city, of tracking traffic flow to increase road travel efficiency, has turned into a nightmare scenario in which people’s faces are being routinely tracked, and all of a sudden these same people, activists or members of social movements, are getting arrested in the dead of night. So I think that we need to be very aware of these urban innovations that proclaim an ethos of efficiency and transparency but enable a much less benign system of control. I believe we have to keep our eyes on China now, because it shows little restraint in employing invasive technologies like facial recognition and AI against parts of the population that are seen to challenge the regime. Soon we will see what these technologies do when exported elsewhere, and meanwhile we will have little to do with their development, since human rights action in China is simply dismissed as Western imposition.

dasgupta: And crimes in space?

weizman: Well, as an example, you catch me two days before a very important presentation on the police killing of Mark Duggan in 2011. My team and I are going to Tottenham to show the results of our analysis, first to the family, friends and the community and then to the public through the media. We were using spatial and architectural technologies and techniques in order to investigate. We spent a year trying to understand a period of one and a half seconds, from the moment Mark Duggan left the minicab until he was shot. That time duration is a black hole in the history of London and much is at stake. Was he holding a gun in his hand when he was shot, as the police watchdog claims? Did he throw it? How did the gun arrive at the grass in the park where the police eventually retrieved it? Does the police version of events make sense? Was the investigation adequate and competent? There was a protest outside Tottenham Police Station asking the same questions days after the event. By refusing to answer those questions, the London Met guaranteed that a protest turned into a riot in which many Londoners were incarcerated.

A small scale analysis of a micro-incident can have large political significance. This is something that architectural modelling helps us to do, because we can see the relationship between the housing estates around the bridge, the park, the road and everything that happened there. Simply by putting the scene in a 3D environment and running through a large number of possible scenarios, we can see that something is wrong in the official version. So here – this is an example of how architectural techniques and technology could shed light on incidents that other techniques could not, and contribute to accountability on behalf of the most vulnerable people in society.