During the drought summer of 1980, Jim Corbett was hiking with a herd of goats in California’s Baja desert when one of the bucks started pursuing a feral doe. Corbett knew he was in danger of losing the whole herd and thus his means of survival. After sprinting for miles and finally bringing the goats under control, he was exhausted, overheated and dehydrated. The only water source was a rancid pool, its surrounding rocks coated in vulture droppings. ‘The greenish water smelled of carrion and seethed with putrefactive bacteria,’ he recalled. Knowing that it was all that lay between him and death, he drank and drank, regaining enough energy to lead the goats to a fresh spring. ‘I spent the night drinking water that took just a few seconds to go through me, but nightlong diarrhoea was much better than being dead.’

The book in which he describes this episode, Goatwalking (1991), is one of the most thrillingly awkward books I know: an ornery, inspiring encyclopaedia of radical theology, politics and goat husbandry, written with an almost pained tenderness towards all things living. The writer Jim Harrison described it as ‘cranky, brilliant, unlovable and true’. It is also, sometimes, so diffuse and oblique that you wish its author had been sterner in corralling its excesses. As well as being a reflection on Corbett’s life as a rancher, environmentalist, Quaker and migrant-rights activist, the book is a manifesto for the revival of pastoral nomadism – leading goats from pasture to pasture and surviving on their milk and wild plants – as the lightest-footed way to live in the arid US where Corbett spent most of his life. ‘From the Alps to the Empty Quarter, Java to Baja, with the goat as a partner, human beings can support themselves in most wildland environments.’ In the preface, conscious of the book’s scattershot hybridity, he concedes that it is ‘for saddlebag or backpack – to live with a while, casually. It is compact and multifaceted, but for unhurried reflection rather than study. It is woven from stargazing and campfire talk.’

In its very exuberance, Goatwalking can seem like the antithesis of the landscape that inspired it – the Sonoran Desert of southern Arizona. In 2015 I spent ten days living alone in a one-room strawbale cabin in the desert about thirty miles from Corbett’s home city of Tucson. The hills and washes were lined with ocotillo, paloverde, creosote bush and the candelabra forms of saguaro cactus; the nights were noisy with cicadas and coyotes. The desert was teeming with life, but you could not fail to be aware that it was a lethal place – what the anthropologist Jason De León has called a ‘land of open graves’. Every year many dozens, perhaps hundreds, of undocumented migrants die here as they attempt to enter the US on foot.

The cabin was built by the Cascabel Conservation Association, an organisation co-founded by Corbett, who died in 2001, as a retreat for those who wish to spend time alone in the desert. ‘To learn why you feel compelled to remake and consume the world,’ he advises, ‘live alone in the wilderness for at least a week. Take no books or other distractions. Take simple, adequate food that requires little or no preparation. Don’t plan things to do when the week is over. Don’t do yoga or meditation that you think will result in self-improvement. Simply do nothing.’

The book is a call to arms, but it’s also a rawly exposing biography. A section on humane slaughtering practice, for instance, segues (I won’t say ‘seamlessly’) to reflections on the author’s decision to disconnect his father’s life-support system. We learn that when Corbett’s marriage ended abruptly in his late twenties, he withdrew alone to Black Bear Mountain in the borderlands, where he taught himself Malay, ‘a language I’d never heard, spoken on the other side of the world by a people I’d never met’. From there he went to Berkeley, where he planned to become a philosophy teacher – ‘but the main thing I learned from studying philosophy was that I knew nothing to teach’. In California he had an epiphany: one day, without warning, his heart simply stopped. ‘Out of the stillness that I thought was death, love enlivened me – or something like love, that doesn’t split, the way love does, into loving and being loved.’

It wasn’t death; it was something more significant. He gave away everything he didn’t need and took to the road. ‘The first lesson is where everyone starts: despair that clears the way.’

*

Spliced between passages about the virtues of ‘going cimarron’ (a cimarron is ‘a domesticated animal or slave that goes free’) and explaining goatwalking’s Talmudic heritage are essays on goats’ hatred of getting their feet wet, efficient milking technique, and the heroic ‘errantry’ of Corbett’s hero, Don Quixote (‘sallying out beyond a society’s established ways, to live according to one’s inner leadings’). Goatwalking can be seen as a kind of scrapbook of a lifetime’s painful thinking. Its most insistent message, however, is the obligation to provide sanctuary.

In the early 1980s the civil wars in El Salvador and Guatemala were at their most grotesque: even at the time, the atrocities committed by government death-squads in both countries were well known in the US. In the border town of Nogales, Corbett heard about a baby boy whom Guatemalan soldiers had mutilated and slowly murdered while forcing his mother to watch. In order to maintain its stance that escapees from the violence were not refugees but economic migrants, the US government was obliged to deny that human-rights abuses were occurring. (To make such a concession would also have rendered illegal the military assistance it was providing to the countries’ respective regimes.)

In 1981, Corbett began accommodating undocumented Salvadoran refugees in the converted garage of his home in Tucson. The numbers swelled when he started to bring Central Americans over the border himself – accompanied by his goats. For each individual act of assistance, he was committing a felony punishable by up to five years’ imprisonment. Goatwalking had found a humanitarian purpose to which it seemed ideally fitted. Many refugees clandestinely crossing the border at this time were helped by a goat-milking co-operative, ‘Los Cabreros Andantes’, of which Corbett was a member. (The name can be translated as ‘the goatherds errant’, a punning allusion to the archetypal caballero andante or ‘knight errant’, Don Quixote.) Goatwalking itself includes several pages of detailed advice on safely and discretely crossing the border and the Rio Grande.

The following year, as numbers increased, a friend of Corbett’s, Pastor John Fife, declared his church, Tucson’s Southside Presbyterian, a place of sanctuary. The Sanctuary Movement, offering shelter to refugees and migrants, spread to churches, synagogues and universities across the US. By the end of the year, fifty Guatemalans and Salvadorans could be found sleeping in Southside Presbyterian on any night. Such was the perceived threat posed by the movement that Southside was infiltrated by undercover FBI agents and paid informants, and in 1985 the recordings they secretly made were used to indict Corbett, Fife and fourteen others, including two Catholic priests and three nuns, on charges of abetting ‘illegal aliens’. The party immediately resumed its work and sued the Attorney General. To the activists’ surprise, the government, perhaps wary of the bad publicity of being sued by nuns, agreed to drop the charges – and, extraordinarily, to stop deportations of Central American refugees currently in the country.

One of Goatwalking’s achievements is to remind us that the human and nonhuman provinces are not discrete from one another. Corbett believed that the principles of justice, community and sanctuary he espoused in his work with refugees ought to be extended to the natural world. The obligation to provide sanctuary, he writes, ‘extends far beyond Central America and specific human refugees to the need for harmonious community among all that lives’. Ecological justice and human justice are not just bedfellows but one and the same. It is a philosophy inspired in part by Aldo Leopold, who in his essay ‘The Land Ethic’ (1949) sought a system of ethics that ‘changes the role of Homo sapiens from conqueror of the land community to plain member and citizen of it’. Goatwalking, according to Corbett, was about ‘learning to live by fitting into an ecological niche rather than by fitting into a dominance–submission hierarchy’.

In 1988 he co-founded the Saguaro–Juniper Corporation (the precursor of the Cascabel Conservation Association). At the heart of the organisation’s philosophy was a ‘covenant’ to hallow the earth, represented by a ‘bill of rights’ for the environment. Among the bill’s tenets were declarations that ‘native plants and animals on the land have a right to life with a minimum of human disturbance’ and that ‘the land, its water, rocks and minerals, its plants and animals, and their fruits and harvest have a right never to be rented, sold, extracted, or exported as mere commodities’. The covenant anticipated today’s burgeoning ‘rights-of-nature’ movement, which seeks to extend to rivers, mountains and forests the same kind of legal rights historically reserved for humans.

In 1995, an area close to Corbett’s home in Cascabel, sixty kilometres east of Tucson, was set to be bought by a right-wing militia for automatic-weapons training. Horrified by the prospect, Corbett and others in the community bought up the 180 hectares of rocky desert and founded what was to become the Cascabel Conservation Association. The militia skulked off and, over the coming years, the association built several simple, isolated residences where outsiders could stay, free of charge, and experience the environment in solitude. The first such building was the strawbale hut.

When I stayed there, I knew I was benefitting from more than just hospitality, but from a legacy and enlargement of Jim Corbett’s commitment to the principle of sanctuary. Any relief he and his associates had felt following their legal triumph against the government in 1985 was short-lived, though, for a new generation of would-be migrants was soon being criminalised. In 2018, thirty-three years later, the remains of 127 dead migrants were recovered from the desert in southern Arizona alone, according to the Pima County Medical Examiner’s Office. In the same year, Scott Warren, a geographer and humanitarian, was charged by US Border Patrol with harbouring unauthorized migrants. Warren was a member of No More Deaths, a humanitarian group that provides assistance to those attempting to cross the Sonoran Desert on foot from Mexico – a direct descendant of the groups Corbett helped to found. Warren faced up to ten years in jail. After a deadlocked trial in June this year, he was retried in November, and – just as Corbett and his friends had been more than thirty years earlier – acquitted on all charges.

*

I did as Corbett advised, and spent those few days without ‘books or other distractions’. But I reflected on his awkward and beautiful and long-out-of-print book, with its unsparing injunctions: be hospitable; honour all life; abide in the world with ‘something like love, that doesn’t split, the way love does, into loving and being loved’.

For more information about No More Deaths/No Más Muertes, and to make a donation, see https://nomoredeaths.org/en/.

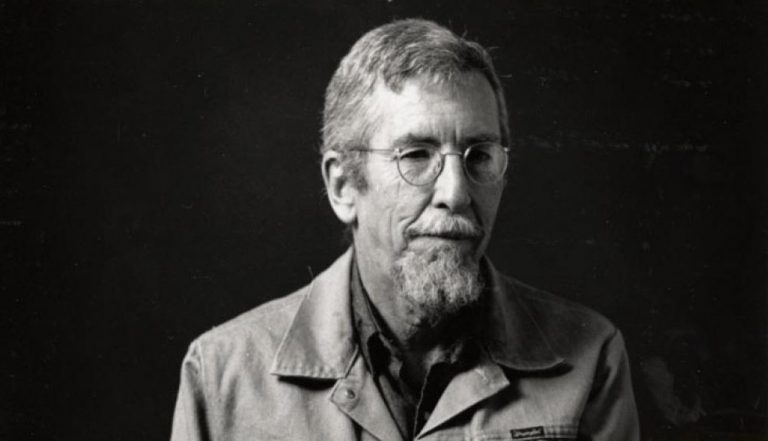

Cover Image © William Atkins. Portrait of Jim Corbett © Arizona Board of Regents for The University of Arizona