On a cool morning in August 1988 Jonathan sprang past the cleaning lady on his way up the stairs. He had been to the market to buy a bag of bread rolls and a bunch of flowers. As he hurried up, taking the stairs three at a time, he ran the forefinger of his left hand along the water lily tiles in the stairwell, holding the flowers and the bag of rolls in his right. The flowers w ere for Ulla, who turned twenty-nine today. She’d put up with him, as she expressed it, for three years now, although he thought he was actually the one who had put up with a lot.

Ulla was still in bed. She knew it was already nearly ten, and she’d realized that Jonathan had gone out for the rolls. She was still in bed because today that was her prerogative. She was thinking about a doll’s house with a library and smoking room that she had seen in a shop on a nearby street: it could be destroyed at the touch of a button and was intended as a form of therapy through which children could channel their destructive urges. Ulla had always been interested in toys: figures with smoke cartridges at the back, wind-up animals that bared their teeth. People could buy little guillotines to celebrate the French Revolution. She could get hold of one and suggest it to the museum director as an exhibit.

*

Now Jonathan was banging about in the kitchen, and shortly afterwards he broke in on the muffled drowsiness of her doze, pulled aside the curtain with a clatter and sat down on the edge of her bed. Congratulations were in order. Jonathan got through the embarrassment of the little ceremony by uttering awkward clichés and stroking his girlfriend vaguely with his right hand, much as one might close the eyes of the dead, while simultaneously laying the breakfast table and setting out the boiled eggs with his left. He had to stand to light the candles and arrange the bunch of flowers, which brought the little ritual to an end.

He poured the coffee and shook the rolls out into the bread-basket. Then he extracted her birthday present from his wallet: a tiny Callot etching that depicted someone being sawn into pieces. He gave her the postage-stamp-sized etching and watched her closely to see what she would say about him giving her such a beautiful present. Bullseye! Ulla devoured the quartering with her eyes – ‘Sweet!’ – and leant it against the candlestick so she could look at it again and again. Then she drew her boyfriend down to her and gave him kisses like fiery little coins, holding his head in both hands as she did so.

When he was restored to freedom he took the post from his jacket pocket and sorted through it. Five letters were addressed to the birthday girl, two to him. She sat up, spread a roll with honey and read the letters, the contents of which were as you would expect.

Jonathan clumsily opened his two letters with his forefinger. One was from the Santubara car factory in Mutzbach – junk mail, presumably – the other from his Uncle Edwin in Bad Zwischenahn. It contained a cheque for more than two hundred marks and the suggestion that he do something sensible with it on this day.

‘Treat yourselves to something,’ his uncle wrote. ‘Enjoy the good things in life.’

Conflicting emotions prevented Jonathan from showing the cheque to his girlfriend, who was busy with her own letters. He left it in the envelope and quickly slipped it into his pocket.

Ulla was from an orderly family; she had money in the bank and gilt-framed ancestral portraits. Jonathan, however, was born on a covered cart in East Prussia in February 1945, in an icy wind and sharp, freezing rain on the trek away from the Eastern Front. His young mother had ‘breathed her last’, as Jonathan put it, in the process. ‘I never knew my parents,’ he would say, usually with indifference. ‘My father was killed on the Baltic coast, on the Vistula Spit, and my mother breathed her last after giving birth to me in East Prussia in 1945.’ As far as suffering was concerned, this guaranteed him an unparalleled advantage over his friends.

That cold February, when calamity struck, his uncle had been driving the cart with its makeshift carpet roof, the pregnant woman tossing about inside the straw. When she went into labour he knocked on farmhouse doors to no avail, and so she died.

Her corpse had been set down quickly and without ceremony in the vestibule of a village church, beside the hymn board with its wooden numbers, and then they had driven on. They had come across a sturdy peasant woman who had lost her child, and she had nursed Jonathan in its place in return for a seat in the cart. Jonathan pictured this as well: the heavy woman sitting in the cart, with himself at her large breast, and the picture more or less corresponded to the reality.

I was suckled by Mother Earth, he would reflect on occasion, and he would stretch, feeling new strength in his veins.

Today Uncle Edwin had sent two hundred marks – the new Avanti sofa bed had been a hit.

Treat yourselves to something? That should be possible. In the meantime Ulla had read her post: from her overbearing mother, her passive father, her psychologist brother in Berlin, and Evie, her goddaughter, whose birthday letter – ‘how are you, I am fine’ – was awkwardly written and decorated with ladybirds. She got out of bed and went over to the bookshelf, where the present she had given herself was standing: a 1950s Danish vase, which the two of them now admired. It was held up to the light, turned this way and that and praised as ‘frightful’. When they had finished with it they stood it on the window ledge alongside various other monstrosities, items that had once been dirt cheap but now had a certain value, or would have if left for a few more years.

Jonathan was embraced again, assured that his little Callot etching had been ‘just right’, and then dismissed. So he went back to his room, which he was happy to do, as the birthday girl was now making phone calls and he had no interest in one-sided conversations.

Jonathan sat down on his sofa. He blew some fluff from the table then stared off into the distance towards the bright window opposite and the portrait of the plump child on the grubby white wall.

He yawned, and his gaze drifted across the weird linoleum geography of his floor. He saw the Isthmus of Corinth, that hair-raising cleft in the rock; he saw a little ship, and steep rock walls to left and right. The water is flowing, he thought, and the ship glided down the canal as if caught in an undertow.

He snapped out of it and read the letter from the Santubara car manufacturer. As it turned out, it wasn’t junk mail but a serious job offer. A Herr Wendland from the factory’s press office wrote that they had been admirers of his discerning prose for quite a while now and were wondering whether Jonathan might fancy a trip to East Prussia; Masuria, to be precise, in present-day Poland. The Santubara Company wanted to set up a test-driving tour for motoring journalists to convince them of the outstanding quality of its latest eight-cylinder model. Any such tour would, of course, have to be carefully prepared in advance. Would Jonathan care to help with this? He could go along on the initial preparatory tour, check out the local culture, see whether there was anything worth visiting in the region – stately homes perhaps, or churches or castles the existence and histories of which might add something to the itinerary. Then he could write an insightful piece about the trip, say twelve pages of typescript

– ‘Masuria Today’ – which they could use to convince journalists that it might be interesting to look around that godforsaken region and take the opportunity of test-driving the new eight-cylinder car at the same time. He would have completely free rein, and they could offer him five thousand marks plus expenses. Travel and accommodation would, of course, be included, so that would be five thousand plus VAT. The precise sum was negotiable.

Masuria? Poland?

Jonathan’s first reaction was no! If it had been a trip through Spain or Sweden, then maybe. But Poland?

No.

On the other hand, five thousand marks . . . And negotiable? Jonathan took down the 1961 edition of the Iro World Atlas

– which he still used simply because that was the one he had – and opened it at the map of ‘German Eastern Territories Under Foreign Administration’. Quite a sizeable chunk, East Prussia. How strange and unnatural the line was, drawn straight across it with a ruler. You saw that sort of thing on maps of colonial Africa or the Antarctic, but in the heart of Europe? It reminded Jonathan of dissection lines in pathology, scalpel incisions in a woman’s flawless white body.

Here was the Vistula Spit, where his father was killed, and the Curonian Spit. Pictures from old geography books came to mind: wandering dunes, elk, a fisherman sitting on his upturned boat mending a net, amber mining.

But the plague arrived by the light of the moon, Swam with the elk across the lagoon.

Jonathan looked for the village of Rosenau, tracing the road with his finger. Here: this was where it happened. This was where he had first seen the light of day, at the cost of his mother’s life. Here, in this village church, was where she had been set down. The young woman had been buried in the churchyard, by the wall perhaps, beneath a laburnum. There was a single photograph of her still in existence, one that had survived their flight. It had been taken at the 1936 Olympics: a young girl in the uniform of the League of German Girls, beret at a jaunty angle over one ear. Jonathan had stuck it to the wall with a drawing pin. The last picture of his father, a young Wehrmacht lieutenant in field uniform and service cap, lay in a folder alongside Jonathan’s birth certificate and bicycle insurance policy.

The tour would start in Danzig, said the letter from the Santubara Company. He would fly from Hamburg to Danzig, where the tour car would be waiting. He could then make notes at his leisure.

Danzig? thought Jonathan. He could use Danzig for his essay on Brick Gothic: ‘The Giants of the North’. The Marienkirche was one of the northern giants still missing from his collection. Lübeck, Wismar, Stralsund: he had seen these cities with their medieval colossi, and that was all well and good, but he had no first-hand sensory impression of Danzig, and it would be difficult for him to describe it in an essay.

If he accepted the commission he could kill two birds with one stone. As well as earning some money he would be acquiring knowledge at the same time, which, in turn, could later be converted into more money.

Jonathan washed his hands as meticulously as a surgeon, looking out of the window all the while. A class of school-children was swarming on the other side of the Isebek canal, a teacher anxiously herding them together – ‘Don’t fall in!’ – while up in the sky a huge aeroplane was coming in to land at Fühlsbüttel.

I’m here in Hamburg, and I’m making a living, thought Jonathan. What’s East Prussia to me? And a single great image arose in his mind’s eye, of Uncle Edwin entering the church with the dead woman in his arms – where to put her? – and setting her down on the steps. The folds of her white dress stained with blood.

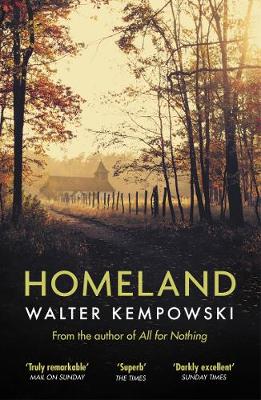

The above is an excerpt from Walter Kempowski’s Homeland, translated from the German by Charlotte Collins, and available now from Granta Books.