Freud would understand. I long for Rome, but there is always something unsettling, perhaps disturbingly unreal about Rome. Very few of my memories of Rome are happy ones, and some of the things I wanted most from Rome, Rome just never gave me. These continue to hover over the city like the ghost of unfledged desires that forgot to die and stayed alive without me, despite me. Each Rome I’ve known seems to drift or burrow into the next, but none goes away. There’s the Rome I saw the first time, fifty years ago, the Rome I abandoned, the Rome I came looking for years later and couldn’t find, because Rome hadn’t waited for me and I’d lost my chance. The Rome I visited with one person, then revisited with another and couldn’t begin to weigh the difference, the Rome still unvisited after so many years, the Rome I’m never quite done with, because, for all its imposing, ancient masonries, so much of it lies buried and out of sight, elusive, transient and still unfinished, read: unbuilt. Rome the eternal landfill with never a rock bottom. Rome my collection of layers and tiers. The Rome I stare at once I open my hotel window and can’t believe is real. The Rome that never stops summoning me, then throws me back to wherever I’ve come from. I am all yours, it says, but I’ll never be yours. The Rome I forgo when it becomes too real, the Rome I let go of before it lets go of me. The Rome that has more of me in it than there is of Rome itself, because it isn’t really Rome I come looking for each time, but me, just me, though I can’t do this unless I seek out Rome as well. The Rome I’ll take others to see, provided it’s mine we’ll visit, not theirs. The Rome I don’t want to believe could go on without me. Rome, the birthplace of a self I wished to be one day and should have been but never was and left behind and didn’t do a thing to nurse back to life again. The Rome I reach out for yet seldom touch, because I don’t know and may never learn how to reach out and touch.

Not a speck of me is Roman any longer, and yet once I’ve emptied my suitcase in Rome I know that things are in their right place, that I have a center here, and that Rome is home. I have yet to discover them but there are, so I’m told, about seven to nine ways to leave my apartment and head down the hill of the Gianicolo to Trastevere, but I am reluctant to learn shortcuts yet; I like the slight confusion that delays familiarity and lets me think I’m in a new place and that so many new things are open and possible. Perhaps what makes me happy these days is that I have no obligations, can afford to do whatever I please with my time, love spending my evenings sitting at Il Goccetto, where witty and smart Romans come to while away the hours before heading home for dinner. Some even change their minds while they’re drinking, as happened to me a few times, and end up having dinner right then and there. I like this Roman way of improvising dinner when all I’d planned for was a glass of wine. After wine sometimes I’ll buy a bottle and head back to Trastevere to visit friends. On certain evenings, when I wish to go home, I avoid the bus and go up the hill on foot.

On my way across the Tiber at night I love to see the illuminated Castel Sant’Angelo with its pale ocher ramparts glowing in the dark, just as I love to see St Peter’s at night. I know that at some point I will reach the Fontanone and stop to stare at the city and at all of its glorious floodlit domes, which I know I will miss soon enough.

I love where I am staying. I have a balcony that overlooks the city. And when I’m lucky, a few friends will drop by and we’ll drink while gazing out at the city by night like characters in a Fellini or Sorrentino film, wondering in silence perhaps what each of us still lacks in life or would want changed, or what keeps beckoning from across the other bank, though the one thing we wouldn’t change is being here. To paraphrase Winckelmann, life owed me this. I’ve been owed this moment, this balcony, these friends, these drinks, this city for so long.

This could actually be my home. Home, says a writer I’ve read recently, is where you first put words to the world. Maybe. We all have ways of placing markers on our lives. The markers move sometimes; but some are anchored and stay forever. In my case, it’s not words, it’s where I touched another body, longed for another body, went home to my parents and, for the remainder of the evening and the rest of my life, would never banish that other body.

It was a Wednesday evening, and I was just coming back from a long walk after school. I used to like wandering about the center of the city late afternoons, arriving home just in time to do my homework. Before taking the bus, I would frequently stop at a large remainders bookstore on Piazza di San Silvestro and, after riffling through a few books, seek out the book I had come for: a thick volume by Richard von Krafft-Ebing, Psychopathia Sexualis. There were several large, hardbound volumes on sale in that bookstore, and by now I knew the ritual. I would pick one up, sit at a table and sink into a prewar universe that was beyond anything I could ever imagine. The book was intended for medical professionals and was, as I discovered years later, intentionally obscure, with segments rendered in Latin to discourage lay readers, to say nothing of curious adolescents eager to navigate the uncharted, troubling ocean called sex. And yet as I pored over its arcane and detailed case studies on what was called inversion and sexual deviancy, I was transfixed by its wildly pornographic scenarios that turned out to be unbearably stirring precisely because they seemed so matter-of-fact, so ordinary, so unabashedly cleansed of moral stricture. The individuals concerned could not have seemed more proper, more urbane, more serenely well behaved: the young man who loved to see his girlfriend and her sister spit in his glass of water before drinking it all up; the man who loved to watch his neighbor undress at night, knowing that the latter knew he was being watched; the timid girl who loved her father in ways she knew were wrong; the young man who stayed longer than he should in the public baths – I was each of them. Like someone who reads all twelve horoscopes in the back of a magazine, I identified with every sign of the zodiac.

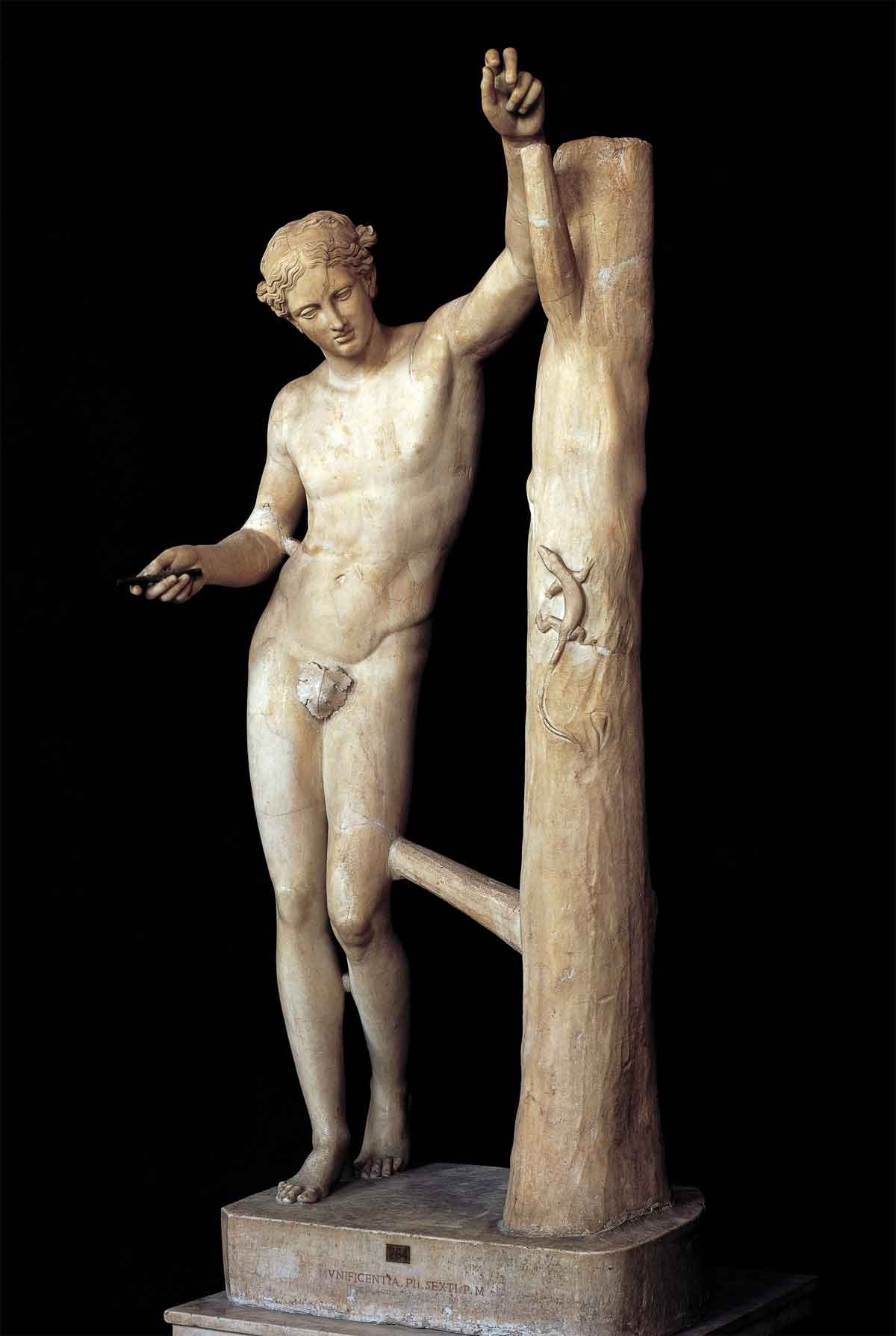

After reading Krafft-Ebing’s case studies, I would eventually have to take the 85 bus for the long ride home, knowing that my mother would have dinner ready by the time I was back. Lightheaded after so many case studies, I knew I’d eventually suffer from a migraine and that the incipient migraine, coupled with the long bus ride, might trigger nausea. At the station before boarding the bus there was a newspaper and magazine kiosk that also sold postcards. I’d stare at the statues, male and female, longingly, then buy one, adding some postcards of Roman vistas to conceal my purpose. The first card I bought was the Apollo Sauroktonos. I still have it today.

One afternoon, after leaving the bookstore, I spotted a large crowd waiting for the 85 bus. It was cold and it had been raining, so once the bus arrived we all massed into it as fast as we could, hurtling and jamming into one another, which is what one did in those days. I too pushed my way in, not realizing that the young man right behind me was being pushed forward by those behind him. His body was pressed to mine, and though every part of him was glued to me and I was completely trapped by those around us, I was almost sure that he was pushing into me so overtly and yet so seemingly unintentionally that when I felt him grab both of my upper arms with his hands, I did not struggle or move away but allowed my whole body to yield and sink into his. He could do with me whatever he wanted, and to make it easier for him, I leaned back into him, thinking at some point that perhaps all this was in my head, not his, and that mine was the guilty, unchaste soul, not his. There was nothing either of us could do. He didn’t seem to mind, and perhaps he sensed that I didn’t mind either, or perhaps he didn’t pay it any heed, the way I too wasn’t quite sure I did. What could be more natural in a crowded bus on a rainy evening in Italy? His way of holding my upper arms from behind me was a friendly gesture, the way a mountain climber might help another steady himself before moving further up. With nothing to hold on to, he had grabbed my arms. Nothing to it.

I had never known anything like this in my life.

Eventually, steadying himself a bit, he let go of me. But as the doors of the bus closed and the bus started to sway, he immediately grabbed on to me again, holding me by the waist, pushing even harder, though nobody around us could tell, and part of me was sure that he himself still couldn’t tell. All I knew is that he would let go of me once he’d steadied himself and held on to one of the hand bars. I could even tell he was struggling to let go of me, which is why I pretended to stagger away from him only to lean back, as soon as the bus stopped, to prevent him from moving.

Part of me was ashamed that I’d allowed myself to do to him what I’d heard so many men did to women in crowded spaces, while another part suspected that he knew what we were both doing; but I didn’t know for sure. Besides, if I couldn’t really fault him, how could he fault me? But I was swooning and doing everything I could not to let him pass. Eventually he managed to slip between me and another passenger, which is when I got a good look at him. He was wearing a gray sweater and a brown pair of corduroys and looked at least seven or eight years older than I was. He was also taller, skinny and sinewy. He finally found a seat in front of me and, though I kept my eyes on him hoping he would turn to look back, he never did. In his mind, nothing had happened: crowded bus, people slithering their way between people, everyone almost lurching and holding on to someone else – it happens all the time. I saw him get off before the bridge somewhere on Via Taranto. A sudden sickness began to seize me. The headache I had feared before stepping into the bus, stirred by the gas fumes, turned to nausea. I needed to get off earlier than I meant to and walked the rest of the way home.

I didn’t throw up that evening, but when I got home I knew that something genuine and undeniable had happened and that I would never live it down. All I wanted was for him to hold me, to keep his hands on me, to ask nothing and say nothing, or, if he needed to ask, to ask anything, provided I didn’t have to talk, because I was too choked up to talk, because if I had to talk I might have said something right out of the cloying, bookish, fin de siècle universe of Krafft-Ebing, which would have made him laugh. What I wanted was for him to put an arm around me in that man-to-man way that friends do in Rome.

I returned to Piazza di San Silvestro many times afterward, always on Wednesdays, read from Krafft-Ebing for a while, stared at the statue of Apollo on display in the magazine kiosk, made sure I wore the same clothes I’d worn on the day I’d felt him lean into me, boarded the bus at the same hour. I saw one crowded bus come after the other and I know I waited and kept watching for him. But I never saw him again. Or if I did I didn’t recognize him.

Time had stopped that day.

Now, whenever I come to Rome, I promise to take the 85 bus at more or less the same time in the evening to try to turn the clock back to relive that evening and see who I was and what I craved in those days. I want to run into the same disappointments, the same fears, the same hopes, come to the same admission, then spin that admission on its head and see how I’d managed in those days to make myself think that what I’d wanted on that bus was nothing more than illusion and make-believe, not real, not real.

When I reached home that evening feeling sick and with a migraine, my mother was preparing dinner with our neighbor Gina in the kitchen. Gina was my age and everyone said she had a crush on me. I did not have a crush on her. Yet, as we sat together at the kitchen table while mother cooked, we laughed and I could feel my nausea ebb. Gina smelled of incense and chamomile, of ancient wooden drawers and unwashed hair, which she said she washed on Saturdays only. I did not like her smell. But, as soon as I let my mind drift back to what had happened on the 85 bus, I knew that I wouldn’t have cared what he smelled of. The thought that he too might smell of incense and chamomile and of old wooden furniture turned me on. I pictured his bedroom and his clothes strewn about the room. I was thinking of him when I went to bed that night but, as I let arousal wash over me, at the right moment, I made myself think of Gina instead, picturing how she’d first unbutton her shirt and let everything she wore slide to the floor and then walk up to me naked, smelling, like him, of incense, chamomile and wooden drawers.

Night after night I would drift from him to her, back to him and then her, each image feeding off the other. And like Roman buildings of all ages snuggling into, on top of, under and against each other, body parts stripped from his body were given over to her, and parts stripped from hers were given to him. I was like Emperor Julian, the two-time apostate who buried one faith under the other and no longer knew which was truly his. And I thought of Tiresias who was first a man, then a woman, then a man again, and of Caenis who was a woman, then a man and finally a woman again, and of the postcard of Apollo, the killer of lizards, and longed for him as well, though his unyielding and forbidding grace seemed to chide my lust, as though he had read my thoughts and knew that, if part of me wished to sully his marble-white body with what was most precious in me, another still couldn’t tell whether what it longed for on Apollo’s frame was the man or the woman or something both real and unreal that hovered between the two, a cross between marble and what could only be flesh.

The room upstairs where I fudged the truth each night, and dissembled it so well that, without turning into a lie, it stopped being true, was a shifting land where nothing seemed fixed, and where the surest and truest thing about me could, within seconds, lose one face and take on another, and another after that. Even the self who belonged to a Rome that seemed destined to be mine forever knew that, within moments of crossing over to a different continent, I would acquire a new identity, a new voice, a new inflection, a new way of being me. As for the girl whom I eventually drew to my bedroom one Friday afternoon when we were alone together and found pleasure without love, if she lifted the cloud that was hovering over me ever since the 85 bus, she could not stop it from settling back less than a half-hour later.

Apollo Sauroktonos, Roman copy in marble of the statue by Praxiteles (active 375–326 BC)

I have frequently thought about Rome and about the long walks I used to take after school in the center of Rome on those rainy October and November afternoons in search of something I knew I longed for but wasn’t too eager to find, much less give a name to. I would much rather have had it jump at me and give me a chance to say maybe, or hold me without letting go, as someone did on the bus that day, or coax me with smiles and good cheer the way men flirt when they put up a coy front with girls they know will eventually say yes.

In Rome, my itinerary on those afternoon walks was always different and the goal undefined, but wherever my legs took me, I always seemed to miss running into something essential about the city and about myself – unless what I was really doing on my walks was running away both from myself and the city. But I wasn’t running away. And I wasn’t seeking either. I wanted something gray, like the safe zone between the hand I only wished might touch me somewhere without asking and my hand that didn’t dare stray where it longed to go.

On the bus that evening, I knew I was already trying to put together a flurry of words to understand what was happening to me. I had once heard a woman turn around and curse a man in a crowded bus for being sfacciato, meaning impudent, because in a typical street- urchin manner he had rubbed his body against hers. But now I didn’t know which of us had been truly sfacciato. I loved blaming him to absolve myself, but I also reveled in my newfound courage and was thrilled by the way I’d struggled to block his passage each time he seemed about to release me to move elsewhere on the bus. I had followed my own impulse and didn’t even pretend I was unaware we were touching. I even liked the arrogance with which he had taken me for granted.

All I had at home was my picture of the Sauroktonos. Chaste and chastening, the ultimate androgyne, obscene because he lets you cradle the filthiest thoughts but won’t approve or consent to them and makes you feel dirty for even nursing them. The picture was the next best thing to the young man in the bus. I treasured it and used it as a bookmark.

In the end, I went to find the original in the Vatican Museums. But it wasn’t what I’d expected. I expected a naked young man just posing as a statue; what I saw was a trapped body. I looked for flaws on his body to be done with him once and for all, but the flaw and the stains I found were the marble’s, not his. In the end I couldn’t take my eyes off him. I stared not only because I liked what I was staring at but because such stunning beauty makes you want to know why you keep staring.

Sometimes I’d catch something so tender and gentle on the features of the young Apollo that it verged on melancholy. Not a spot of vice or lust or of anything remotely illicit on his youthful body; the vice and lust were in me, or perhaps it was just the start of a kind of lust that I couldn’t begin to fathom because it was instantly diffused by how humbled I felt each time I stared at him. He does not approve of me, yet he smiles. We were like two strangers in a Russian novel who, before being introduced, have already exchanged meaningful glances.

But then, I remembered, the candor would gradually dissipate from his features, and something like an incipient look of distrust, fear and admonition would settle, as though what he expected from me was remorse and shame. But it’s never so simple: admonition became forgiveness, and from clemency I could almost behold a look of compassion, meaning, ‘I know this isn’t easy for you.’ And from compassion, I was able to spot a touch of languor behind his mischievous smile, almost a willingness to surrender, which scared me, because it asked me to confront the obvious. He’s been willing all along and I wasn’t seeing it. Suddenly I was allowed to hope. I didn’t want to hope.

Today, after being in Rome for a month almost, I am taking the 85 bus. I will not catch it somewhere along its long route, which might be easier for me, but I will take it where the terminal used to be fifty years ago. I will get on the bus at dusk, because this is when I used to take the 85 bus, and I will ride it all the way to my old stop, get off and walk down to where we used to live. This is my plan for the evening.

I expect that my return may not bring me much pleasure. I never liked our old neighborhood with its row of small stores that peddled overpriced merchandise to people who are almost all pensioners now, or young salesclerks who live with their parents, smoke too much and cradle large hopes on meager incomes. I remember hating the square balconies jutting out like misbegotten shoeboxes from ugly squat buildings. I’ll walk down that street and ask why I always want to come back, since I know there’s nothing I want here. Am I returning to prove that I’ve overcome this place and put it behind me? Or do I return to play with time and make-believe that nothing essential has really changed, either in me or in the city, that I am still the same young man and that an entire lifetime has yet to be lived, which also means that the years between me-then and me-now haven’t really happened, or don’t really matter and shouldn’t count, and that, like Winckelmann, I am still owed so much?

Or perhaps I’ll come back to reclaim a me-interrupted. Something was sown here, and then, because I left so soon, it never blossomed but couldn’t die. Everything I’ve done in life suddenly pales and threatens to come undone. I have not lived my life. I’ve lived another.

And yet, as I walk around my old neighborhood, what I fear most is to feel nothing, touch nothing and come to grips with nothing. I’d take pain instead of nothing. I’d take sorrow and think of my mother still alive upstairs in our old building rather than just walk by, probably with some degree of haste, eager to catch the first taxi back to the center of Rome.

I get off the bus at my old stop. I walk down the familiar street and try to recall the evening when I came so close to throwing up. It must have been in the fall – same weather as today. I walk down the same street again, see my old window, pass by the old grocery store, imagine my mother miraculously still upstairs preparing dinner, though I see her now as she was most recently, old and frail, and finally, because I want to arrive at this thought last, I pass by the refurbished film theater where someone came to sit next to me once and placed a hand on my thigh while I took my time before acting shocked when all I wanted was to feel his hand glide ever so softly up my leg. ‘What?’ I had asked. Without wasting a second, he got up and disappeared. What? as if I didn’t know. What? to say tell me more because I need to know. What? to mean, don’t say a thing, pay no mind, don’t even listen, don’t stop.

The incident never went anywhere. It stayed in that movie house. It’s in there now as I’m walking past it. That hand on my thigh and the young man on the 85 bus told me there was something about the real Rome that transcended my old, safe, standby collection of postcards of Greek gods and of the teasing boy-girl Apollo who’d let you stare at him for however long you pleased provided it was with shame and apprehension in your heart, because you had infringed every curve on his body. I used to think at the time that, however disturbing the impact of a real body was against mine, the weeks and months ahead might cast a balm and quell the wave that had swept over me in the bus. I thought I would eventually forget, or learn to think I’d forgotten, the hand I let linger on my bare skin for a few seconds more than others my age might allow. Within a few days, a few weeks, I was sure the whole thing would blow over or shrink like a tiny fruit that falls to the ground in the kitchen and rolls under a cabinet and is discovered many years later when someone decides to redo the floors. You look at its shriveled, dried shape and all you can say is, ‘To think that I could have eaten this once.’ If I didn’t manage to forget, then perhaps experience might turn the whole incident into the insignificant thing it was, especially since life would eventually unload so many more gifts, better gifts that would easily overshadow these fragments of near-nothings on a crowded Roman bus or in an ugly neighborhood theater in Rome.

We remember best what never happened.

I’ve gone back to the Vatican Museums to see my Apollo who is about to kill a lizard. I need special permission to see the wing where he stands. The public is not allowed to see him. I always pay homage to the Laocoön, and to Apollo Belvedere, and to the other statues in the Pio Clementino, but it was always the Apollo Sauroktonos whom I longed for and whom I’d put off seeking. The best for last. It’s the one statue I want to revisit each time I’m in Rome. I don’t have to say a word. He knows, by now he surely must know, always knew, even back then when he’d see me come by after school, knowing what I’d done with him.

‘Have you ever tired of me?’ he asks.

‘No, never.’

‘Is it because I’m made of stone and cannot change?’

‘Maybe. But I too haven’t changed, not one bit.’

How he wished he could be flesh, just this once, he used to say when I was young.

‘It’s been so long,’ he says.

‘I know.’

‘And you’ve grown old now,’ he says.

‘I know.’ I want to change the subject. ‘Are there others who’ve loved you as much?’

‘There’ll always be others.’

‘Then what singles me out?’ He looks at me and smiles.

‘Nothing, nothing singles you out. You feel what every man feels.’

‘Will you remember me, though?’

‘I remember everyone.’

‘But do you feel anything?’ I ask.

‘Of course I feel, I always feel. How could I not feel?’

‘For me, I mean.’

‘Of course for you.’

I do not trust him. This is the last time I see him. I still want him to say something to me, for me, about me.

I’m about to walk out of the museum when my mind suddenly thinks of Freud, who surely must have come to the Pio Clementino with his wife or his daughter or with his good friend from Vienna then based in Rome, the curator Emanuel Löwy. Surely the two Jews must have stood there a while and spoken about the statue – how could they not? And yet Freud never mentions the Sauroktonos, which he must have seen both in Rome and in the Louvre during his student days. Surely he must have thought about it when writing about lizards in his commentary to Jensen’s Gradiva. Nor does he mention Winckelmann except once, Winckelmann who, himself, surely must have seen the original bronze version of the statue every day during his tenure in Cardinal Albani’s home. I know that Freud’s silence on the matter is not an accident, that his silence means something peculiarly Freudian, just as I know he must have thought what I myself thought, what everyone seeing the Sauroktonos thinks: ‘Is this a man who looks like a woman, or a woman who looks like a man, or a man who looks like a woman who looks like a man . . .’ So I ask the statue, ‘Do you remember a bearded Viennese doctor who’d sometimes come alone and pretend he wasn’t staring?’

‘A bearded Viennese doctor? Maybe.’

Apollo is being cagey again, but then so am I.

But I remember his final words. They were spoken to me once, and he repeated the exact same ones fifty years later: ‘I am between life and death, between flesh and stone. I am not alive, but look at me, I’m more alive than you are. You, on the other hand, are not dead, but were you ever alive? Have you sailed to the other bank?’ I have no words to argue or reply with. ‘You found beauty but not truth. You must change your life.’

Photograph of Apollo Sauroktonos, Roman copy in marble of the statue by Praxiteles (active 375–326 BC), © Vatican Museums and Galleries, Vatican City / De Agostini Picture Library / G. Nimatallah / Bridgeman images