In the Moncton area of New Brunswick where I’ve lived all my life, we Acadians say it is practically unnecessary to learn English because we catch it effortlessly, like a common cold. If I happen to be listening to songs or reading a book in English, it is natural for me to keep thinking in English for hours, sometimes days, afterwards. Living where English is the majority language, I am constantly making micro-decisions to revert back to French, thereby asserting my cultural origins. But my code-switching apparatus does get tired, and at times the easy way out becomes the only way out. And the easy way out is very often English.

For instance, it made perfect sense to me to write this essay in English rather than French since I am primarily addressing myself to an English readership, but I am certain that if I had written on this subject in French, my starting point and my approach would have been different. This is only natural, I think.

This constant movement between French and English is like the flutter of emotions one may experience on any given day: the emotions may be somewhat annoying or exhausting, or somewhat pleasurable, and within a certain range they are no cause for worry. There is a tipping point, however. There is the comfort zone, and there is the discomfort zone.

For decades now, I have been trying to understand the role of language, the impact it had and has on life, on evolution. I am past the point of accepting expedient or superficial explanations. I do not adhere to the notion that one’s native language – or ‘mother tongue’, as we say in French – is some kind of Rock of Gibraltar, creating an equivalent Mediterranean pool in which one’s heart, mind and soul swim as gracefully as dolphins, drawing some inextinguishable force from this primeval basin so old and deep that this identity can never be shaken. In fact, I’ve rather come to suspect that our relationship to our mother tongue is not primarily sentimental or emotional, but deeply physiological and that constant and untimely disruptions and repetitive stresses induced by changing language and cultural channels cause what could be called a linguistic neurosis. I have no way to prove this of course, but I certainly wish someone would.

The notion of linguistic neurosis has probably never occurred to anyone who has not had to function, in any important way, in a language other than their mother tongue. To them, the concept would probably be summed up as being ‘just a fuss’. Of course, this perception only serves to feed the neurosis instead of soothe it.

Neurosis usually implies some form of rigidity and as much as I dislike rigid attitudes, I have also come to embody them. For example, I very much like the idea of wordless books, especially for children who cannot yet read. My attention was recently drawn to such a book: Sidewalk Flowers by JonArno Lawson and Sydney Smith. Praise for this book was such that I purchased a few copies to give to young families I knew, plus one copy to keep as a coffee-table book in our own home. The only problem is the title, which is in English.

Growing up, it was a family principle to always offer birthday, Christmas and other types of greeting cards in French and where one could buy such French cards in Moncton became a real problem, because the vast majority of stores selling English cards did not bother to carry any in French. For many Acadians, it became a mission to persist in asking to have an assortment of cards in French. Many similar demands were expressed concurrently during the 1960s and 1970s, from greeting cards, books and magazines to catalogues, flyers, telephone services and various official documents. Slowly but surely, an expanding number of Acadians started reminding everyone around them of their existence and their specific language needs – needs which eventually morphed into rights. French schools and colleges, hospitals and many other public services came to embody the extent to which the authorities acknowledged the French Acadian culture.

The publication and production of Antonine Maillet’s series of dramatic monologues La Sagouine (The Charwoman) in 1971 marked a turning point for Acadian French. And in 1979, when Madame Maillet went on to win the Goncourt for her novel Pélagie-la-Charrette, it certainly made a lot of us feel acclaimed and recognized, finally, in a big way. And so, literature saves us after all.

Why am I telling you all this? Because to this day, I feel uncomfortable displaying an English-titled book on our coffee table.

The truth: the three copies bought haven’t moved from the shelf where I deposited them on the day they were delivered, for even though it is a wordless book, the title sends the wrong message. The wrong message? The message to young children and their parents that it is okay and normal to read English books. The good message is to put a French storybook on the table, even if it has no words in it. So there it is: yes, I am a pusher of French. And in view of the Acadians’ habit, perhaps born of necessity at first, of accommodating the English authorities, the fact of standing up for the French language is very often viewed as uncompromising, or rigid.

At the outset of the Seven Years War (1756−1763), Acadia, with its 10,000 inhabitants, was one of the five territories grouped and known as New France. The other four were Canada (55,000 inhabitants), Louisiana (4,000 inhabitants), Hudson Bay and Newfoundland. Acadia was comprised of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Île Saint-Jean (Prince Edward Island), Île Royale (Cape Breton) and Gaspesia. As the British Empire was gaining control over North American territories then under French rule, the Acadian settlements, which mostly dotted the Bay of Fundy area, came to be viewed first as an annoyance, and then, when these French descendants asked the British conqueror to exempt them from swearing an oath of allegiance to the Crown of Great Britain for fear of having to take arms against their own in other settlements, a threat. The English suspected that the situation would become unmanageable and a better solution to the problem was found: the forced removal of Acadians from Grand-Pré and the Minas Basin of Nova Scotia, a large area including south-eastern New Brunswick today.

The Great Upheaval (known as la Déportation or le Grand Dérangement) was intended to disperse the Acadians in port cities along the New England coast as far as New Orleans, in order to discourage them from regrouping and forming any sort of legitimate identity. And so they were boarded onto ships and their houses, barns and fields set on fire behind them, so as to dampen their desire to ever return. The Great Upheaval was, to put it mildly, disastrous for the Acadians; their population was decimated and their way of life irreparably damaged through shipwrecks, disease, poverty and displacement.

Acadians hung on to their French heritage as best they could after la Déportation, in 1755, up to the turbulent 1960s. Of course they had defined and identified as Acadians in the years between, but mostly in a non-provocative manner. There were flare-ups here and there, but mostly the English held the money and the power, and kept things going their way. Acadians learned to bend when there was no other choice and so it is no surprise that the French Acadian language and culture suffered losses through those years. French schooling was minimal and what there was of it remained a constant subject of bickering. Older Acadians remember that it was forbidden to speak French in many workplaces, even well-established and respected Canadian corporations. Consequently, for a very long time, Acadians mostly kept to themselves, earning their living, often with difficulty, from agriculture, forestry and fishing.

It is thus no surprise that twentieth-century Acadian French remained somewhat cloistered in the eighteenth century. The language hardly modernized because most of its locuteurs kept on living and working in much the same way as when Acadia was founded. It is true that the establishment, by Catholic congregations, of a dozen or so French-language colleges contributed highly to the evolution of the language as well as to raising awareness of Acadian history and mistreatment, but by the 1960s, when I myself reached the age of reason, many Acadians in the Moncton area were either ashamed of their ‘bad’ French, or they didn’t care much about the language issue because they had other things to worry about.

More than 260 years have passed since the Great Upheaval, which officially lasted eight years. The Acadian people survived and our culture thrives (relatively speaking) to this day. In the last fifty years, officials have expressed regrets and governments have listened to our grievances and have enacted measures to support Acadian culture.

Hanging on to the French language and culture in North America today is no mean feat, especially where there is no critical mass to make the language and the culture sustainable. This, I would say, is what distinguishes the feat of Acadians from that of the Québécois. Lacking an established territory over which we could govern ourselves according to our own needs, the existence of our language has become the ultimate record of our unique history and culture. In other words, our visibility and our affirmation as a people is established through our language. Consequently, any erosion of our French feels like an erosion of identity, an erosion of territory, an erosion of ourselves.

Nearly a dozen historical pockets of French-speaking Acadian communities live on in the Atlantic provinces of Canada today, all cousins to Louisiana’s Cajuns, all speaking their particular brand of French. Of these, Chiac is probably the most painful one to come to grips with. This idiom, spoken in the south-eastern area of New Brunswick, where I was born and grew up, is a mélange of old and modern French with a generous proportion of English words and syntax thrown into the mix. Chiac is generally viewed as bad French, even by us Acadians. Only very recently has it been considered a demi-mal, a sort of shield we use to protect ourselves from caving in completely to the omnipresence of the English language.

In our family, Chiac was not encouraged and never written, and if I managed to write six of my books without using Chiac, it is mainly because I avoided all use of dialogue. After each book, I was conscious of having warded off, yet again, the moment when I would have to face the dragon and come to terms with the Chiac dilemma: how could I write dialogue that genuinely represented and reflected my origins and experiences without using Chiac?

At some point in my writing career it was put to me that whatever problem I had or have with Chiac may well be resolved by writing about it, which I have done extensively, especially in my novel Pour sûr, published in 2011.

When I did begin to write using Chiac, it was very enjoyable. Here I could feel how I was not simply writing, but truly recreating the sensibility I best knew. The grammatical aspects of writing Chiac were not easy to tackle, and in this I faced the complexities of putting spoken language into written form. For so long I had simply assumed that a spoken language automatically had a textual counterpart. All in all, the experience was both exhilarating and nerve-racking. Breaking the taboo, I felt, demanded an explanation. And then nuances, and then again more explanations. I could not simply throw Chiac out into the world without them. I was conscious of breaking this language taboo, and I did not break it mindlessly. I wanted to give this language issue a good look at.

Today, many years later, I cannot say that my apprehensions have been put to rest. I see there may well be no end to Chiac. It will probably even flourish given its high degree of malleability. But the question is, will Chiac thrive at the expense of French, or will it in fact transform or even replace French? This is a loaded question.

I sometimes think that I am not much of a writer, lacking the depth often born of tragedy. From the start, my specific way of writing – fragmentary skeletal novels – was born of my problem with Chiac and it is mainly by experimenting with structure that I somehow manage to produce books. The mostly young and endearing characters that populate my works seem to have no serious concerns other than this perplexing language question. Can this linguistic tension in one of the world’s most civilized countries be considered a tragedy? I suspect that for most readers, it is hardly even a subject of interest. Childhood, family life, community, gender issues, politics, the environment, these are all touched on in my books, yet language is the thorniest subject of all.

I was, like many others, brought up to be made very conscious of our French Acadian roots, and guided, sometimes forcefully, towards all things French. I remember the familiar Grolier encyclopedia and a series of mid-sized vinyl records called La Ronde des enfants, a collection of stories for children. Household belongings that some of us seven or eight children would eventually stumble upon and maybe take interest in, in French. There was always this preoccupation, this need to strengthen our connection to the wider French-speaking world. In the 1960s and 1970s, the French language became synonymous with international opportunities, but even for me, blessed with academic abilities and an above-average incentive to learn French correctly, it has not been an easy task. The pressure of English – a universal language, to boot! – is so great that many a French idiom gets lost in the flood.

Nevertheless, as paradoxical as it may seem, I am often dismayed by the poor quality of French I hear around me. My ears are abuzz with errors of all sorts that I would be tempted to blame on sheer laziness or nonchalance. And yes indeed, it hurts to hear French spoken mostly in English. I respect that, for many, language is simply a tool, and Chiac may well be as good a tool as any. Who am I to question? But Chiac does not correspond to the entirety of my identity, and as such I refuse to give it all the room it wants.

In the course of any normal day in Moncton, I often hear English spoken with what I believe is a French Acadian accent. And I am left in awe when, upon my asking, these people tell me that they do not speak French. This has happened to me so many times that I am beginning to think that the anglophones around us have started speaking ‘our’ brand of English – that the deep French roots of our history have somehow permeated the English language. When I respond by saying that I thought these people were Acadian because they seemed to speak with the Acadian accent, many of them sort of freeze up, or at least show some discomfort. The tear, the rip lies there also, confirming again that something hurts.

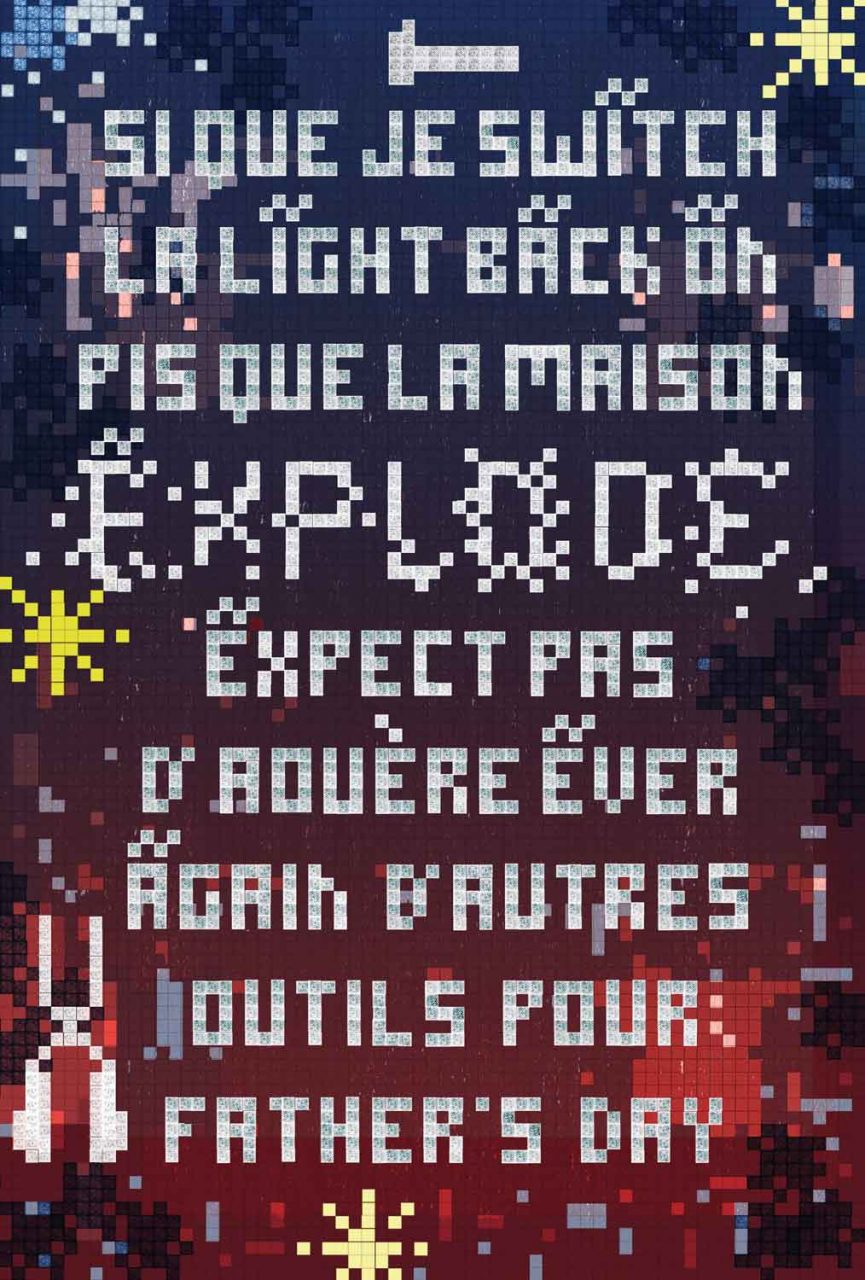

Artwork and detail © Lucille Clerc, from Pour Sûr (2011), a novel by France Daigle