- On 6 March 1901, James Joyce wrote a fan letter to Henrik Ibsen, wishing the playwright a happy birthday. He was an eighteen-year-old undergraduate at the time, and, remarkably, had just managed to get a review of Ibsen’s latest play published in the prominent Fortnightly Review. The Norwegian playwright, having read the review, sent his compliments to Joyce via his translator. The young Irishman was understandably elated, and wrote gushingly to the older writer: ‘I can hardly tell you how moved I was by your message . . . to have earned a word from one who held so high a place in your esteem as you hold in mine.’

- With the centenary of Anthony Burgess this week, we find ourselves turning back to his ‘Art of Fiction’ interview with the Paris Review. The interviews took place while he was delivering a series of lectures on Joyce, and the conversation is a love letter to the author of Ulysses. He ‘can’t be imitated’, Burgess tells us. ‘You can’t use Joyce’s techniques without being Joyce’, just as ‘You can’t write like Beethoven without writing Beethoven, unless you’re Beethoven.’ Nabokov, on the other hand, is ‘unworthy to unlatch Joyce’s shoe’.

- While fan mail can be flattering, not everyone can hope for the insightful paeans received by Ibsen or Joyce. For Shirley Jackson, fan mail was often ‘irrational and annoying’. She put her letters into categories: the kind that ‘asks if I’m the Shirley Jackson who taught fifth grade in Toledo, Ohio, in 1902’; that ‘says I have stolen the correspondent’s name for one of the characters in a book’; or in one instance, claimed that a picture of Jackson in a magazine showed her ‘with a dog that was stolen from him several months ago; I was either to send him back his dog or a check for the dog’s sentimental value, which he set at two hundred dollars’.

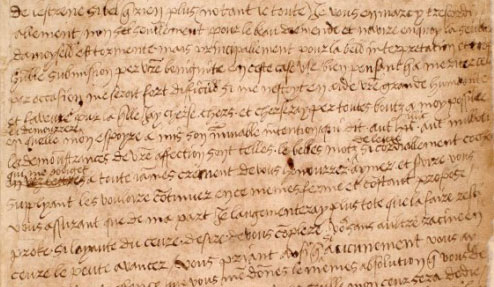

- The progenitor of fan mail is surely the love letter. England’s most famous, or at least most regal wooer-by-way-of-words, is Henry VIII, who in 1528 wrote a love letter to Anne Boleyn pledging his eternal love and support to the lady in waiting. Never mind that he had been married to Catherine of Aragon for twenty years. ‘I promise to . . . serve you only,’ wrote Henry, asking Anne to become his number one mistress. Seven years later, with Catherine divorced and Anne beheaded, Henry wrote letters of striking similarity to Jane Seymour, his new crush: ‘The bearer of these few lines from thy entirely devoted servant will deliver into thy fair hands a token of my true affection for thee’.

- While Henry VIII must hardly have expected the evidence of his inconstancy to be pored over by scholars of the future, other correspondents write letters with the public in mind. In an open letter to Wikipedia, Philip Roth takes the website to task over the inaccuracies it propagates regarding his life. ‘Dear Wikipedia, I am Philip Roth,’ he begins, complaining that an English Wikipedia Administrator did not view him to be a credible source on his own life.

- Between 1946 and 1975, Iris Murdoch corresponded with the French poet and novelist Raymond Queneau, a successful author sixteen years her senior. Published for the first time in Granta, the letters show the devotion of a fan and the colloquialism of a friend: ‘I feel most impatient to see you in English. I hope your play is going down well?’ Sadly, for us, the correspondence remains one-sided – it is likely that Murdoch destroyed all of Queneau’s letters to her.