At first I thought of suggesting Nabokov’s trippy, disturbing dreamscape of a novel, Invitation to a Beheading, serialized in a Russian émigré magazine in 1935 and 1936. The unfortunate protagonist, Cincinnatus C., is sentenced to death by decollation for the ambiguous and victimless crime of ‘gnostical turpitude’, which makes him ‘impervious to the rays of others’ and creates a ‘bizarre impression, as of a lone dark obstacle in this world of souls transparent to one another’. His crime, in fact, was being sentient in a world of puppet-like characters – intolerant of his dimensional quandary he remains in prison without knowing his day of execution. The novel is about cruelty, about oppression of the individual, it’s also about the loneliness of art. But then I discovered a communicating vessel with the work of the extravagant Argentine writer and poet, Silvina Ocampo, whose work Italo Calvino admired because it ‘unfolds within a feminine world as if it were a hidden continent, a labyrinth of individual prisons’.

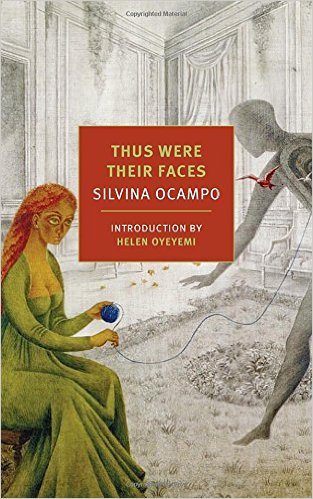

Silvina Ocampo was an iconic figure for several generations; Alberto Manguel, Manuel Puig, Alexandra Pizarnik and Edgardo Cozarinsky, and the feminine point of the inseparable tripartite constellation that included Jorge Luis Borges and Adolfo Bioy Casares, both of whom are immortalized in statues together in Recoleta, without her always enigmatic – one could say ‘opaque’ – presence, for some reason, that would turn the false binomial into the truer triad. An excellent collection of her stories, Thus Were Their Faces (NYRB, with an introduction by Helen Oyeyemi), spanning from 1937 to 1988, includes Borges’s prologue, which highlights what he calls her ‘strange taste for a certain kind of innocent and oblique cruelty’.

Borges considered her one of the greatest poets of the language, ‘She sees us as if we were made of glass, sees and forgives us. It is useless to try to fool her.’ She saw transparent souls, the cruelty of innocence, and wrote to expiate fear. ‘Writing is having a sprite within reach,’ she wrote to introduce her stories, ‘something we can turn into a demon or a monster’. In the end it’s all that really matters, what she writes, and not the statue; ‘that is what we are, not some puppet made up by those who talk and enclose us in a prison so different from our dreams’.