I grew up in Hollin Hills, a suburb outside Washington DC, of 458 modernist, glass houses. Just beyond the land of federal buildings, marble and granite, columns and porticos and subdivisions of center-hall colonials, Hollin Hills was a place of narrow lanes, shared parks and no fences, of Eames chairs and stainless-steel cutlery. In Hollin Hills, we believed our flatware could change the world.

My parents were Democrats and involved in liberal politics. As a kid, we campaigned at every election – my first was for Jimmy Carter, when I was eight, and I remember McGovern’s 72 defeat keenly. My dad devoted his life to building rural cooperatives in the US and abroad. ‘Owned and operated by the people they serve’ was the mantra of my childhood. My father believed that capital should stay in communities and that cooperatives could help everyone, particularly the least privileged. Trained as an economist, my mother worked as a bookkeeper but was mostly a mom. She was the one who chose the house while my dad was working abroad, and they moved in a few months after I was born.

The front and back of the house are all glass, and it perches perilously at the top of a hill with 47 steps snaking up from the street. Hidden in the trees, it looks as if it’s suspended in their boughs. Inside, a chimney made of reclaimed brick cuts through both floors and divides the open-plan spaces as if they spiral out from it. My bedroom was downstairs where the house hunkers into the ground, and the windows start at the level of the lawn. I’d often stand before the glass walls at night and wonder who might be on the other side.

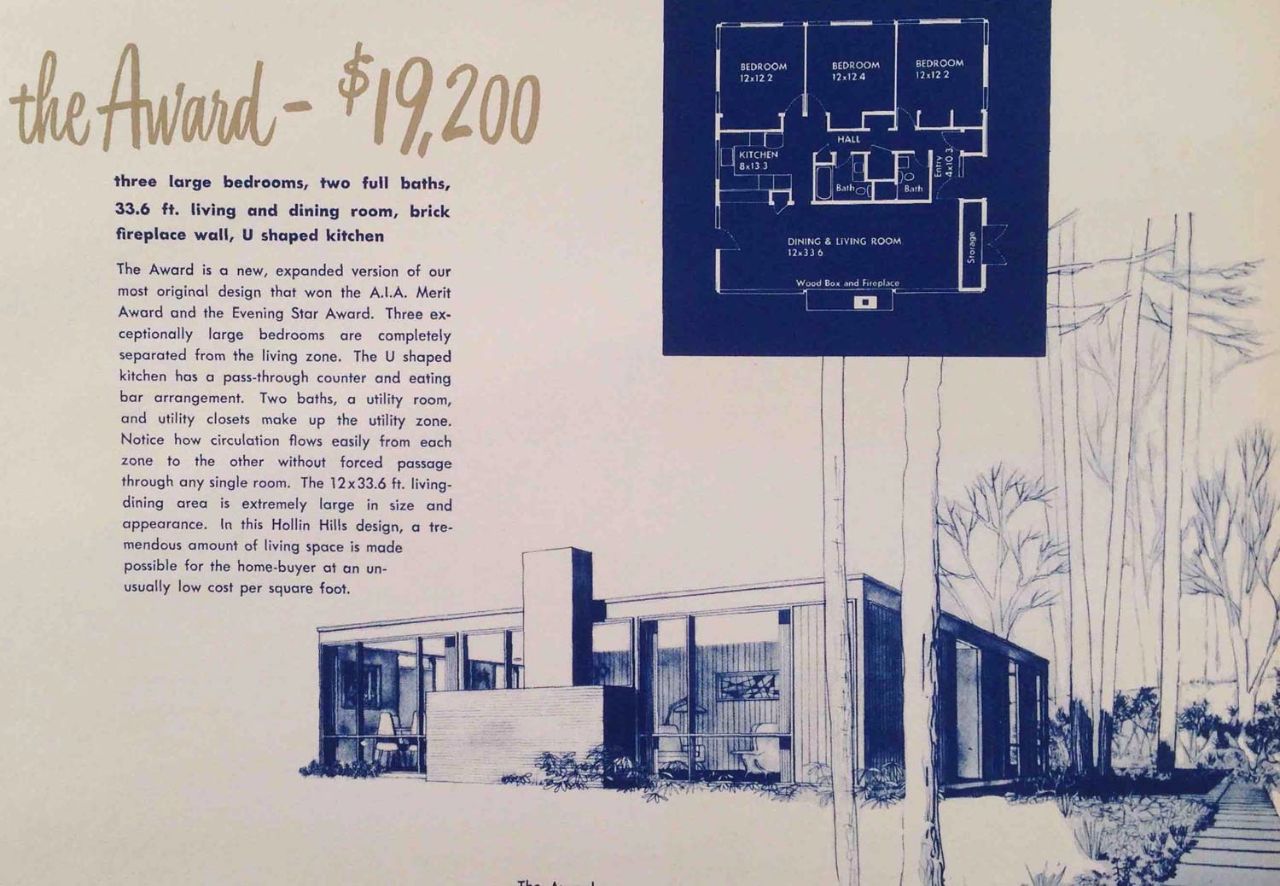

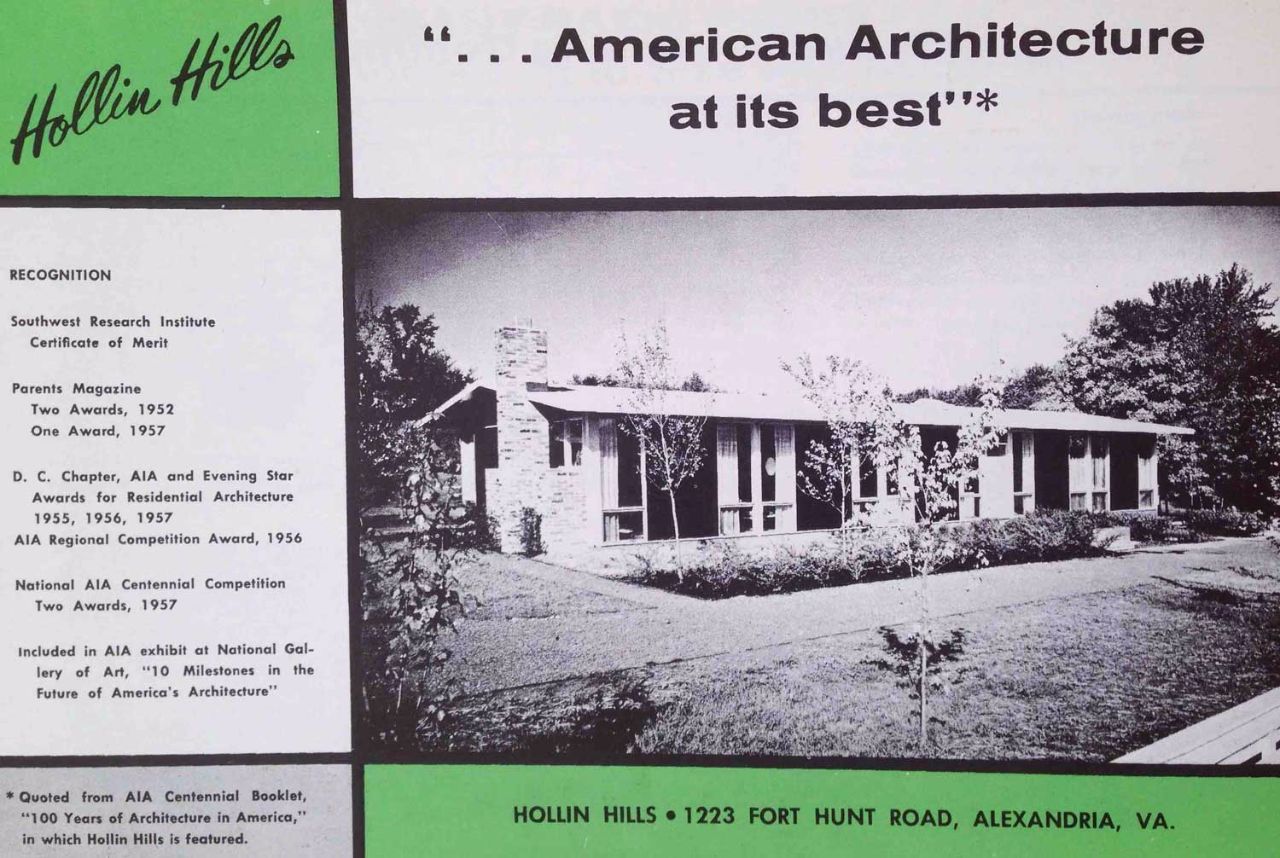

Hollin Hills’ 1953 model was praised by a curator at MoMA, and called ‘Mondrian-like’ by the New York Times Magazine.

I didn’t love modernism, not at first. I wanted to fit in, which for me, at my elementary school, meant church on Sunday and a colonial home. The place I wanted to live would have a canopy bed with a ruffled skirt at the bottom, and my name would be ‘Cabot’ not ‘Kabat’. My parents were aghast at these dreams of normalcy, and responded by teaching me modernism’s principles. In our house everything came with a lesson. The gray Eames chair was ‘mass-produced and affordable for all.’ I even knew what my parents paid for it. Seven dollars. Then there was Russel and Mary Wright’s Guide to Easier Living, a book written by a modernist potter and his wife that provided detailed instructions for a newer, simpler life. The opening pages have drawings of fussy chairs with Xs through them.

With modernism life would be better because it was streamlined. Homes were pared back, and housework would be measured, regulated, simplified, just like on production lines. The factory moved to the domestic realm. Corbusier declared the home ‘a machine for living in,’ and said that architecture could solve ‘social unrest.’ These homes and their furniture were also going to fix social problems like poverty, as if aesthetics were linked to amelioration.

My parents moved to Hollin Hills around the time that the US started calling modernism the International Style. It was an aesthetic of any place and no place and was applied mostly to corporate headquarters, the UN and housing projects. In Hollin Hills, nature, sun and light, architecture and design, form and function all represented a new form of idealism.

The community was a kind of utopia. When it was founded, all the residents believed in hope and change. My parents arrived to communal co-ops, collective parks and collective baby-sitting. People banded together. There were committees for everything from water to trash. A Viennese magazine called it a ‘colony of intellectuals.’ The families that came here chose someplace new and different: walls of glass, reclaimed brick, open plan, open lives.

The architect of Hollin Hills, Charles Goodman, described Hollin Hills by saying, ‘These houses attract the kind of people who don’t think the world is perfect.’ What did that mean? My father believed humanity was ever improving and architecture was part of the process. For him perfection was achievable; that was what progress meant. It went in one direction – better—and modern design would speed us on our way. But how? And how did everyone here in Hollin Hills have such faith? What did they believe was going to happen in these houses? Were they supposed to improve their occupants? Or the world? I wish I could know how Goodman’s words sounded then.

*

I stand in the street and look up at the house where I was raised. I’ve come back to Hollin Hills to try to understand its magic. My father has been dead for five years, and in the time between his death and this moment, I’ve found myself rebuilding my parents’ modernist home in a remote valley in upstate New York. Clearly their values have a hold on me, so much so that I didn’t even think rebuilding the house was suffused with meaning. I didn’t think about it at all—not until my architect joked about how I was designing the Oedipal home.

I know it wasn’t just my family that lived the modernist dream. Four hundred and fifty-eight other families did too in Hollin Hills. That’s more than a thousand people. But what brought them all here? How did they come to idealise modernism? It seems so impossible today, but who wouldn’t want to believe something as simple as a seven-dollar chair could make the world a better place?

Only a handful of original residents remain. When my parents arrived in 1956, Hollin Hills was seven years old. My mother’s parents helped with the move and when my grandmother got there, she quipped, ‘Why would anyone want to live in a beach house in the woods?’

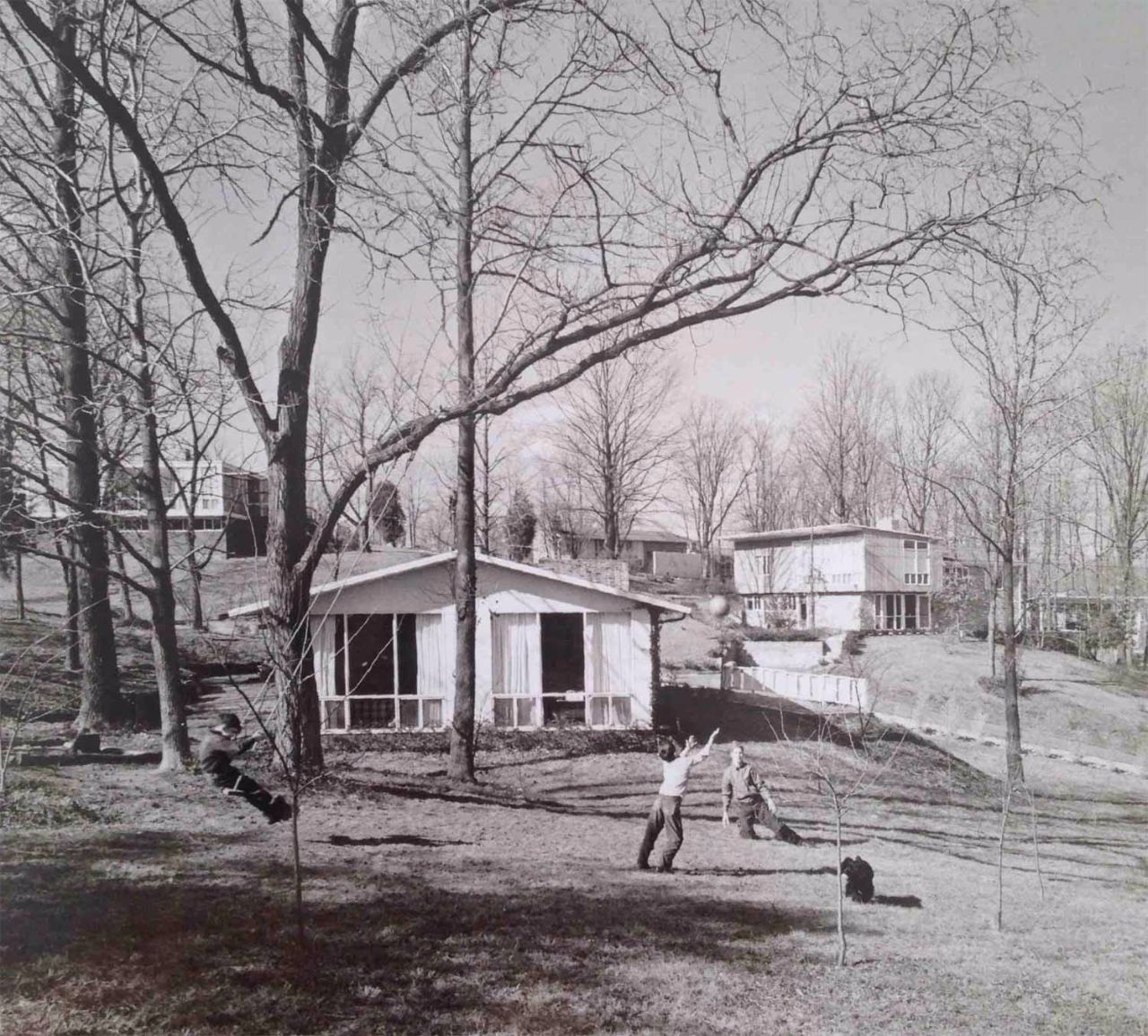

This photo by W. Eugene Smith of Hollin Hills was included in the American Institute of Architect’s centennial exhibition at the National Gallery of Art in 1957.

I look at the black-and-white photographs from that time. My mother was twenty-nine and had two baby daughters – my older sisters, who were teenagers when I was born more than a decade later. Kids run in the street dressed as cowboys. A mother who looks like a teenager stands in the midst of them in rolled-up jeans and sneakers. Two boys play catch; another swings from a giant tree. It’s winter in the pictures. The homes are stark in the landscape, surrounded by bare trees. Spindly black limbs and branches reach for the sky, and those dark lines emphasize the slender white mullions holding up the walls of glass. The homes had high ceilings and low dividing walls, clerestories, and open plans, as if life were moveable and full of possibility.

Hollin Hills was built by Bob Davenport and Charles Goodman. Davenport had been a government employee working in the Agriculture Department during the New Deal and Goodman was a modernist who’d had government contracts during the War and built the National Airport in Washington (now Ronald Reagan National Airport). I grew up hearing stories about both of them: the architect’s inflexibility, the developer’s generosity. They shared a vision of what they wanted from Hollin Hills and, in 1946, they walked the hills and plotted a suburban development that would be different, that they’d be ‘proud of.’ The land, though, was in Virginia – bordering the last vestige of George Mason’s original plantation, and not even five miles away was Alexandria, which had been home to one of the biggest firm of slave traders in the country. It’s hard to imagine building a progressive community in the segregated South – but that is what they did.

They talked about fitting homes into nature rather than forcing nature to submit to housing. Inside and outside would blur together, boundaries would be frowned upon. To this day, fences are banned in Hollin Hills, and the homes have been sited so the land itself feels shared, while in an act of benevolence that became legendary, Davenport deeded parcels to the subdivision for communal parks. More importantly, the only restrictive covenants were to protect the architecture of the homes – not keep people out based on race, like the covenants in many other subdivisions built across the US at this time.

My parents originally wanted to move to Maryland, which was not segregated but politically corrupt. Virginia was the last place they saw themselves living, yet here was a community of like-minded Democrats who all voted for Adlai Stevenson – the last progressive to run for president – living in modernist houses and taking up leftist causes in the most unlikely place.

I stand in my childhood bedroom and pore over the clippings my mother kept about the community. DC punk posters are still tacked on the walls where I’d hung them as a teen. ‘This is Hollin Hills,’ announces a sales brochure, with the jaunty self-assurance that assumes we should already know Hollin Hills, or at least want to. Next I find a personal letter from Davenport welcoming my parents to the subdivision. ‘Hollin Hills,’ he typed, ‘is a unique community . . . You like all the others who are now living here or will be here later have been attracted by a new and different type of architecture, far ahead of conventional design.’

Far ahead. You are, he’s saying, far ahead of the others because this place is ahead of everywhere else.

The 1953 sales brochure lists all of Hollin Hills’ awards. Inside it promises the famous landscape designer Dan Kiley will create your garden plan.

It’s summer and uncommonly cool for Virginia. I walk through the streets and think about the idea of specialness the community cultivated. Roads dead-end in cul-de-sacs, houses are tucked into trees, hidden in the boughs. Ceilings soar, second stories cantilever out. One mimics the line of the roof as if the whole building were leaping into the air. Others have rooftops that wave like a butterfly. Some models, no bigger than a double-wide, come with thirty feet of glass across the facade. Another you can see clear through. In one of the communal parks, the trees arch overhead like something out of Ruskin’s Nature of Gothic. A fox darts from the path, and I think about how the earliest residents called themselves ‘pioneers’ to try and capture the sense of adventure that came with moving here – or maybe it was a sense of ordination. For one small second I think of this as ‘the city upon a hill’.

The more I think about the line, the more it feels like it fits. John Winthrop used it in his sermon to the Puritans on the decks of the Arbella when they were about to land in America. He was telling them the world would be watching, and that their new society would be an example to all. The first residents of Hollin Hills also felt like a promised people in a promised land. They were embattled; there was no municipal water, no paved roads, no phone lines, no trash pick up, no mail delivery. The nearest school was a two-room schoolhouse with a potbelly stove. People had to contend with the land. This language of struggle, of us against the world, of the world watching, this sense of mission, this was Hollin Hills.

My oldest sister Ellen remembers the sense of ‘freedom’ and ‘openness’. These are the qualities she associated with the community as a kid. It was being able to run around in the woods; the homes were open, nature abounding. Today she dates an architect who grew up here as well. He explains that the notion of transparency in the homes carried through to the way you could cut through the neighbors’ yards. He not only lives in the community, he lives in his parents’ old house. We’re in the living room, and I’m sitting on the same leather sofa my parents have. Its teak arms curve out delicately, as if it were an abstracted version of a chesterfield with thin teak legs. The only difference is Roger’s is black leather, my parents’ a caramel shade that makes me think of the early 70s, and every place I go there’s a sense of déjà vu. The homes are all furnished similarly. ‘There was,’ he says, ‘a community effort back then. People seemed to do things together.’

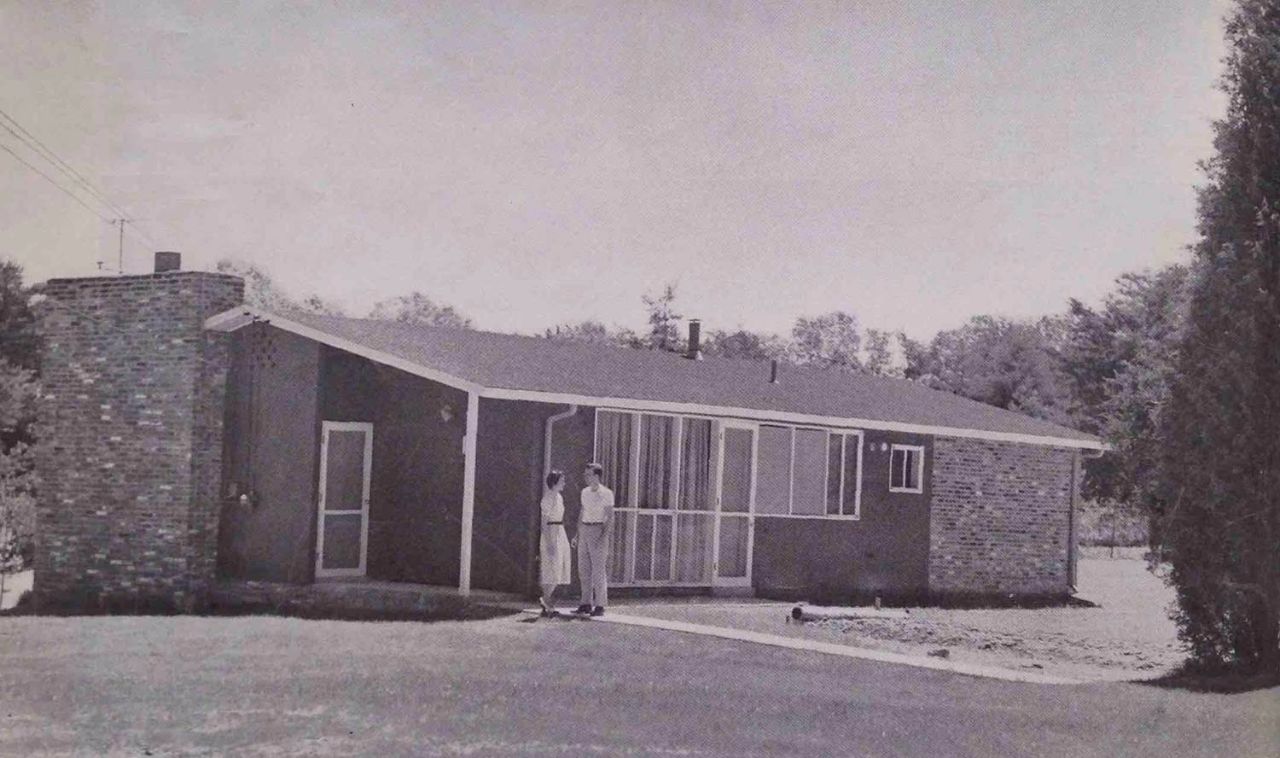

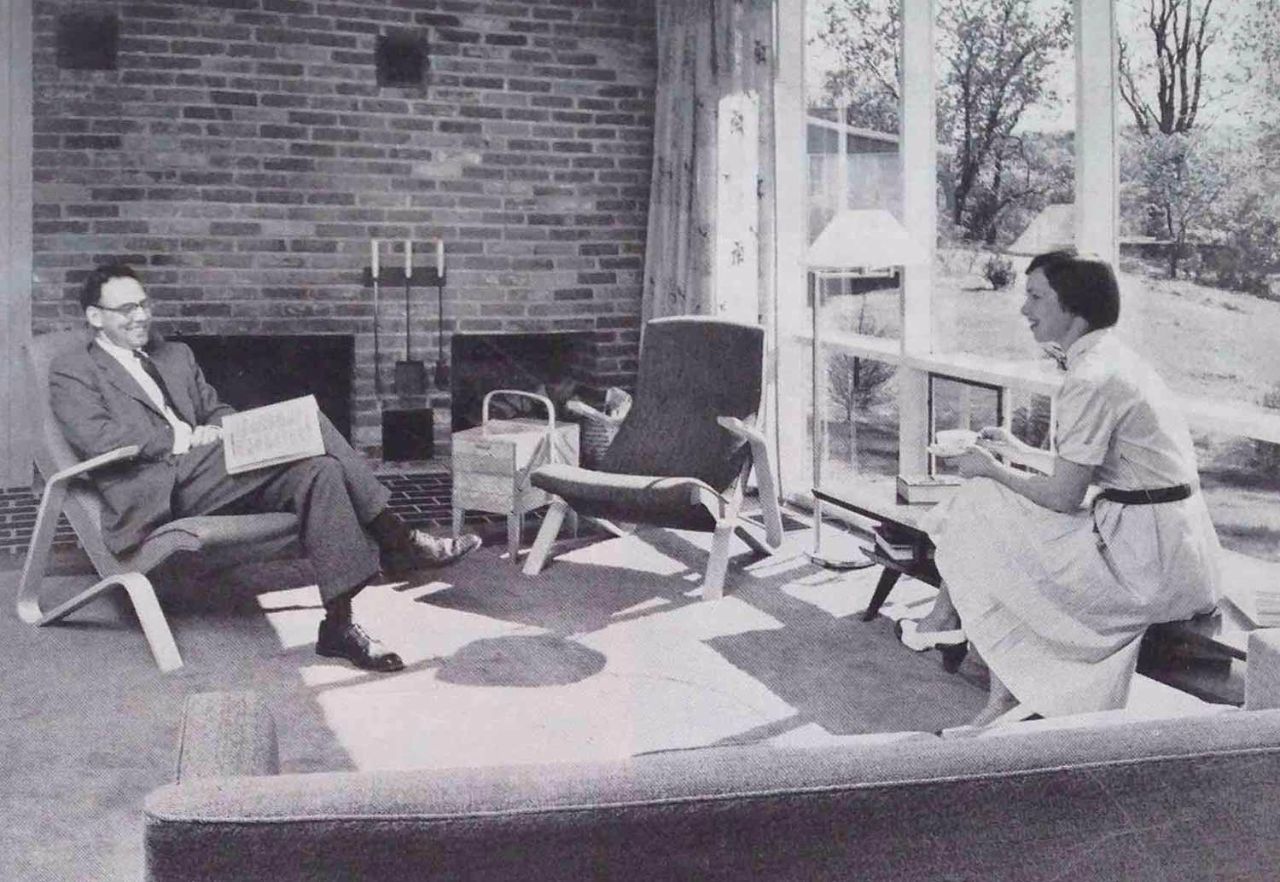

The August 1952 issue of Living for Young Homemakers trumpets on its cover: ‘A new generation wins its spurs in government.’ Inside it features this image of Lars and Kitty Janson. ‘He, a lawyer for the Federal Trade Commission, she a research analyst for national defense.’

How could my father have such faith in progress? His family had escaped the czar’s pogroms, and he and his brother and sister grew up in a small town outside Pittsburgh. During the Depression, they had a cross burned on the lawn and their father lost his store. My father and his siblings all served in World War II. My uncle lost his leg to a shark in the Pacific. My aunt was an Army nurse. She’d been at Normandy and the Liberation of Paris, and would say, ‘The things I’ve seen, the horrors –’ but would never specify what those horrors were, at least not to me. My father was in the deadliest branch of the service, the Merchant Marine, posted in an unarmed ship sailing the most dangerous route in the North Atlantic. In his last years, he’d tell me about the sound of boats around his going down. I don’t see anything in those experiences that should lead to an optimism in humankind, but it did.

The year I was born Vietnam was in full swing; Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr. were killed, and my mother was wondering what kind of a world she had brought a child into. For her, hope seemed impossible.

In its earliest years Hollin Hills was a place of communal values, but things had changed. Now it was embattled and encroached upon. Soon after I was born a subdivision of traditional homes was built right behind my parents’. Fake gas lanterns hung down over the front doors there as if to suggest a home should look like an antebellum estate, maybe with slaves. Meanwhile in the US – and in Hollin Hills – war divided us. President Johnson started Vietnam and advanced civil rights and social welfare. Come Watergate, traditional politics was tainted and the change everyone had valued seemed far, far away. My dad, though, still believed in fighting to change the world, even with compromises attached.

*

I visit the few remaining people who moved here in the 1950s to ask what Hollin Hills meant to them then. Marjorie Hemmendinger waves me into her living room and apologizes about the furniture. ‘I believed,’ she says, ‘in modern architecture, although you wouldn’t know it looking around now.’

She has lofty white hair framing her face and glossed lips. She is just over 90. Her skin is smooth and her voice assured, and there is this word, ‘believe.’ It comes imbued with faith, and when I look around her I recognize the totems of a faith I was raised in too. To me her living room still does look like the modernism I remember from my childhood, with its rust-colored sofa and Japanese screens. On the coffee table are books by Elie Wiesel and Orhan Pamuk. Nearby are Bertoia chairs, as well as a fluted Saarinen table. The names form a pantheon of great American designers. I ask what it meant to ‘believe’ in modern architecture. That’s, I think, what I’m looking for here, to understand this credo.

‘It’s hard to articulate,’ she shrugs.

In her time, though, she wanted to articulate just this. She did a demographic survey of the residents with her neighbor in 1956, to see what kind of people were being drawn here. The project grew out of both hubris and curiosity, or as Marjorie puts it, ‘We were really self-involved.’ She shakes her head. ‘But we wanted to know what had made such a convivial community.’ The survey tabulated faith, age, pay and politics. ‘The great unifying element was education,’ Marjorie tells me. Advanced degrees were common for both men and women. Everyone was a Democrat; most men worked for the government and households earned twice the national average. She says that there was an irony in moving here. ‘You thought you were being adventurous but found a mirror image of yourself.’

In the same issue of Living for Young Homemakers, Kitty Janson recalls that on marrying she and her husband ‘had merely carried over their parents’ ideas . . . and planned a colonial house. A study of new design changed their minds and they built their home in Hollin Hills over parental skepticism.’

Another neighbor, Arnold Edelman, came back to the US after serving as an economist on the Marshall Plan, and moved to Hollin Hills on the advice of an architect friend, but architecture was in his blood. His parents worked on early trade union housing and his grandfather was in practice with Louis Sullivan, of ‘form-follows-function’ fame. I tell Arnold and his wife, Margaret, that I grew up thinking there was a moral imperative to simplicity, to modernism, even to knives and forks.

They laugh, and Margaret quotes Sullivan’s dictate. ‘Those simple straightforward things,’ she says, ‘are better.’ Her voice is ethereal. It tightens as Arnold flicks through the New York Times Magazine and she asks what he’s looking for.

‘I just noticed a couple Wegner chairs in this ad for a ten-million dollar New York apartment.’ He tries to find the page and says how ridiculous it is that these things are being taken for luxury goods. Designed in 1949, the same year my parents married and Hollin Hills’ first homes were built, Wegner’s chair has the low-slung look of a folding deck chair crossed with Mies’ Barcelona one and came with a hook to hang it on the wall. They had been made of rope to fold up and stowaway. Cheap and meant for everyone, now they’re signs of money and taste. The couple explains that this is what Hollin Hills has become since wealthier people have moved in – modernism as an accessory rather than as an ideology.

Down the street from the Edelmans is a house that appears to fly. It sits on a slope and you enter on what seems to be the ground floor only to find miraculously it’s the second. Inside are Tom and Eleanor Fina, both in their 90s, both in blue broadcloth shirts. Tom was in the State Department, and they’d alternate between Hollin Hills and Europe when he was on a posting. He talks about serving as consul general in Milan in the early 1970s. The consulate had been furnished in these grand and traditional mahogany and walnut pieces. ‘They were gracious,’ he says, but not at all fitting the idea he wanted to convey about America. This was an era of strikes – battles between anarchists, socialists and Marxists, and he wanted to create a sense of openness. He used modernist furniture to do this. ‘We got contemporary furnishings. The whole image we were trying to project was one of a contemporary America that was open and progressive.’

Eleanor pushes a plate of cookies my way, and we talk about how these ideas could be conveyed in furniture. They tell me too about the first pieces they bought for themselves. The Paul McCobb table had elegantly tapering legs and leaves that folded down for an ever-changing home. The matching chairs had subtle curves and spindles that arced up, as if simplifying even a Shaker design. My parents bought the same set for their first home. Tom describes them as ‘honest. Not veneered, the wood was solid. It was,’ he repeats, ‘the honesty.’ That language, even the idea that furniture could have a moral quality, seems powerful to me, and Eleanor explains how they discovered Hollin Hills. Like the Edelmans, they’d been told about it by an architect friend. ‘We didn’t want to live where every house looked the same, with little tiny windows and not much light.’ The architect said, ‘Well don’t you know about Hollin Hills?’

*

The furniture was honest; it suggested American values and the homes were also supposed to be the ‘future.’ That was what the American Institute of Architects called it. They included the community in an exhibit at the National Gallery of Art celebrating a century of American architecture. In the association’s archives, I go in search of this future. On a heavy table that hardly seems modern or ‘honest,’ I’m surrounded by the group’s newsletters and minutes of their board meetings. Instead of the future, I find something about those American values. The architects were trying to lobby the State Department. It had begun an ambitious building program for embassies. Various architects have lunch with various officials, and nearly every new US embassy was modern.

This 1958 brochure describes Hollin Hills as ‘a community for the special person whose taste demands something better.’

Soon the organization got money from the State Department to send an exhibition to Moscow. Hollin Hills was included. Kruschev saw the display, and according to Time, ‘endorsed modern architecture over the Russian style.’ This is a modern architecture laden with cultural meaning and Cold War values. Four thousand visitors came a day to the exhibition.

In an article on the exhibition in the Post, Sarah Booth Conroy writes, ‘Viewers should be impressed with the Charles Goodman-designed houses in Hollin Hills, Alexandria, VA. They can tell just by looking, that here a sensible man built houses which have respect for the land and the landscape.’

‘It looks,’ Conroy writes in closing, ‘like quite a country.’

*

It was quite a country. In the 1950s, the CIA covertly sent shows of abstract art to Europe and funneled money to left-leaning literary magazines. The agency’s message was that aesthetics, and modernism in particular, could challenge tyranny. We were a country that embraced the future and the individual. In the Soviet Union all art and architecture were state-sanctioned social realism with its easy-to-decipher message. There, art was part of totalitarianism, designed to transform people into masses. Modernism was America’s response, and art and architecture weapons in the new Cold War.

The architect of Hollin Hills had designed a community for what he called ‘People strong enough to stand unafraid’. That community was, I’m beginning to think, emblematic of an American ideology that flourished during the Cold War. But how? To say that the community represented American values is tricky for me. ‘American values’ now come cloaked in the flag and a nationalism that smacks of exclusion and entitlement rather than openness and progress and the leftist values of Hollin Hills.

*

At home that night, my mother extends the footrest of her La-Z Boy. A crash of metal rings through her house. It echoes against the glass behind her. A La-Z Boy is not very Hollin Hills. Years ago, she’d have scoffed at it—hunter green, padded and tufted with ruffles at the base. Now it’s her most comforting piece of furniture, and the metallic clang still reverberates. The rest of the living room is a set piece of teak and leather, Danish modern furniture bought from the co-op Scan, and abstract landscapes on the wall. She’s a week out of the hospital and wears a robe whose sleeves puff out like a princess’s. Her scrawny legs stick out at the bottom. She wears thick sheepskin slippers though it is July. Her hair is only flecked with gray. Bobby pins hold it back, and in her I see the ghost of my future, the woman I will one day be, at least in looks, maybe more.

I ask about her modernist flatware that we used at dinner earlier and tell her how I grew to love it. The spoon has a delicate curve like the half-moon of a thumbnail, the knife handle a slim ridge that’s ergonomic and elegant. ‘They seemed . . . better.’ I struggle for the word. ‘In their looks, in their simplicity, they seemed like the came with a moral purpose.’

‘But the cutlery was better,’ she says. ‘It was simple.’ She shrugs as if this is obvious and uses the same language the others had – ‘better’ and ‘simple’ and ‘straightforward.’ ‘It was –’ she sets down her wine– ‘just what you need and nothing more.’ She recalls how she and my father bought the set in 1950, just after they were married and just after it was first designed. They were pleased with finding it and pleased with themselves because of the design.

I tell her what amazes me about modernism is thinking that things could improve people, that progress was possible, and that it could be contained in objects and architecture.

‘Yes,’ she says. ‘Isn’t that funny. One thing I loved about your father is that he believed in all of that, in progress and the perfectability of mankind.’

My heart soars. How many 88 year-old women, a week out of hospital for pneumonia, would be talking about enlightenment ideals with their youngest kid?

‘Your father,’ she repeats, ‘believed people were always improving. I loved his optimism for people and progress.’

Here, I am in the city on a hill, in the house atop a hill, that feels like it’s floating in the trees, in a place that feels like a fairytale, a place that believed it had the power to change the world, as if a glass house could be Cinderella’s slipper.

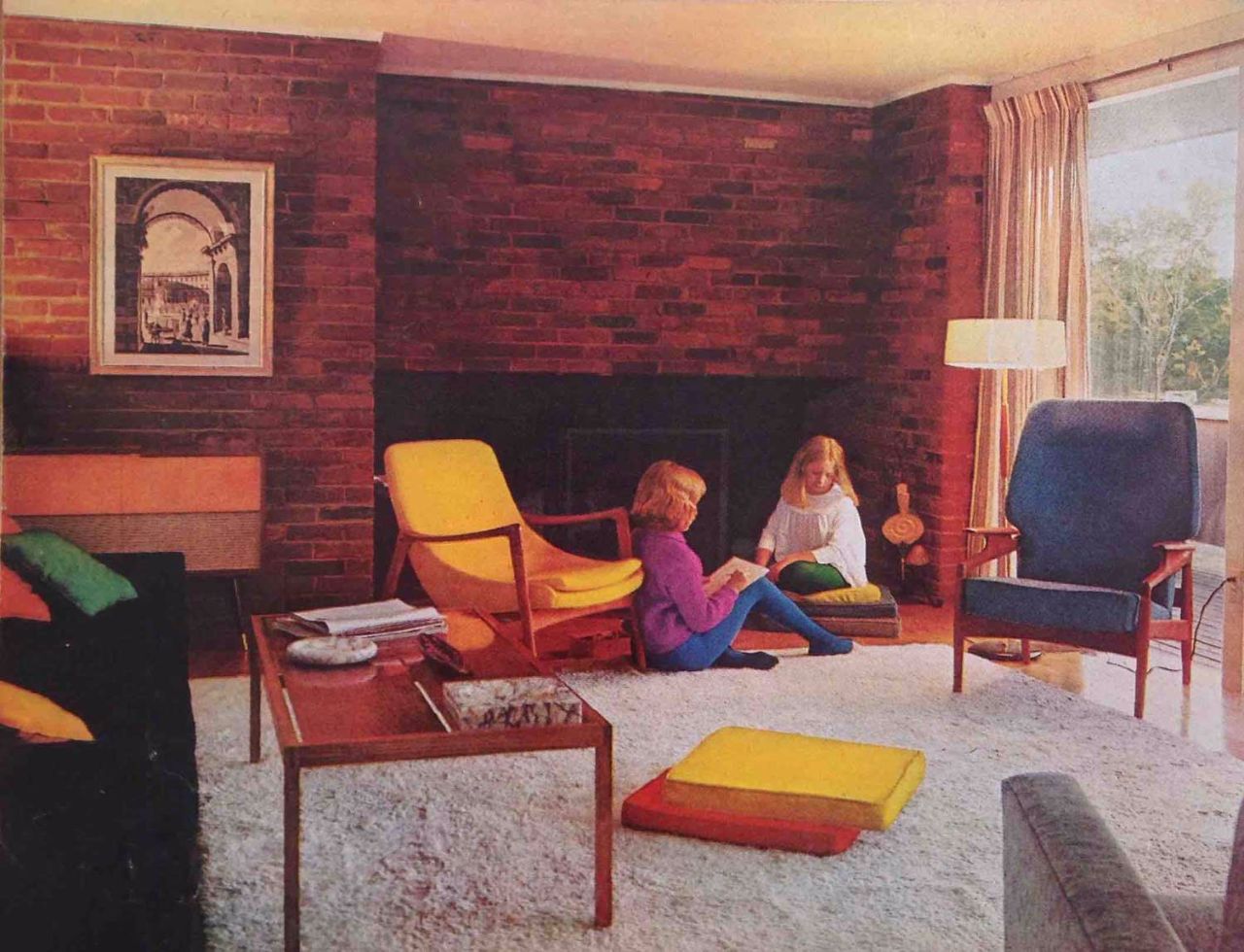

In its 24 November 1962 issue, LIFE headlined this home as ‘A Sensible Buy In The Suburbs.’

I go to visit the architect Michael Sorkin in New York City. He grew up in Hollin Hills, and is now the Nation’s architecture critic. Across from us is a chair from his parents’ house, one of the few things he kept after they died. The air conditioning hums, and Michael describes Hollin Hills as pink and liberal.

‘I also,’ he turns to me, ‘have memories of a lot of CIA types. Our neighbors across the way, David Coffin, he was an old China hand, OSS, CIA.’ I stare at him to make sure I’ve heard him correctly and when I’m sure I’m staring too hard, I focus on his shoes, Puma slides, until that might seem embarrassing too, but Michael seems unbothered. He doesn’t even slow down, as if he’s used to talking about this, as if these facts are a given. These were his neighbors though, and his great aunt had been a party member. One day, he explains, ‘Men in trench coats showed up at the door to check on Coffin.’ Michael tells me his own father was in the Defense Department, and I don’t question how that worked with his aunt’s politics in the 50s with their communist witch hunts. Michael shakes his head and wistfully remembers going to a liberal private school back before the public ones were integrated, and then tells me how their home smelled of teak and linseed oil. His neighbors the Coes, who’d worked on the TVA, one of Roosevelt’s New Deal policies, gave Michael his first subscription to the Nation. Leaving his office I stand on the street corner. Horns honk and afternoon traffic speeds past. I wonder why did architecture and espionage fit so well together? What had I been missing all these years?

*

Hollin Hills was about changing the world, but in ways I never expected. My image of growing up here has the honeyed tinge of age that we would have called ‘Harvest Gold’ in the early 70s. It was a time of war, protest and hippies. My aunt and uncle married in the Field’s house around the corner. I remember guests in dashikis and afros and the long flowing dress I wore. I held wildflowers. Gil Scott-Heron, one of the creators of hip hop, lived up the hill. My parents hosted SDS protesters; my sisters got tear-gassed at rallies. We marched for women’s rights and the ERA. We were a family that supported McGovern and campaigned for Carter. The war we fought was against the one in Vietnam. The first things I remember on TV were images of the dead in East Asia on the evening news at dinner and Ford’s inauguration in the afternoon with my mom and her close friend who worked for the League of Women Voters. My sisters’ bedroom windows were covered in CND stickers and peace signs.

How could there be spies among all of this? One of Michael Sorkin’s other neighbors, not the Coffins but Frank Collins Jr., wrote to the Washingtonian, complaining about an assertion that Hollin Hills had been ‘pink’ and ‘very liberal.’ Collins pointed out that in 1950 on his street alone there were high-level military officers, a Department of Defense lawyer and others working for the government, including himself: ‘I was,’ he wrote, ‘military adviser to an Assistant Secretary of Defense.’ His own clearance levels sound like something Ian Flemming would dream up: ‘Top Secret, Cosmic, Q and other clearances.’ He continued, ‘Elsewhere in the community there were and still are over half dozen senior State Department officials, two lieutenant generals (one headed a major intelligence agency) and at least a dozen CIA employees.’

Yes, most of Hollin Hills was employed by the government. The Cold War was in their careers. It often was their career. My sister’s boyfriend’s father was at the CIA, I learn, and so too was Eleanor Fina. She’d been the agency librarian. Our next-door neighbor, Bill Bader, whose obituary ran recently in the Washington Post, started out in Naval Intelligence, went to the agency and then in the 70s was on the staff of the Senate’s Church committee investigating CIA wrongdoing. I talk about it with my sister Gale, and she says, ‘Didn’t you know, Mr. Godwin was too?’ The Godwins lived two houses away, right next to the Baders. This was Hollin Hills. And this is also my modernism.

I think again of that line, ‘the city on a hill’. The eyes of the world would be watching how the puritans behaved. The same was true for American exceptionalism in Hollin Hills – the proof of our good was in actively helping others, but that foreign aid could hide something more covert. Sometimes persuasion, sometimes spying. The idea of people watching your actions helped justify watching others too.

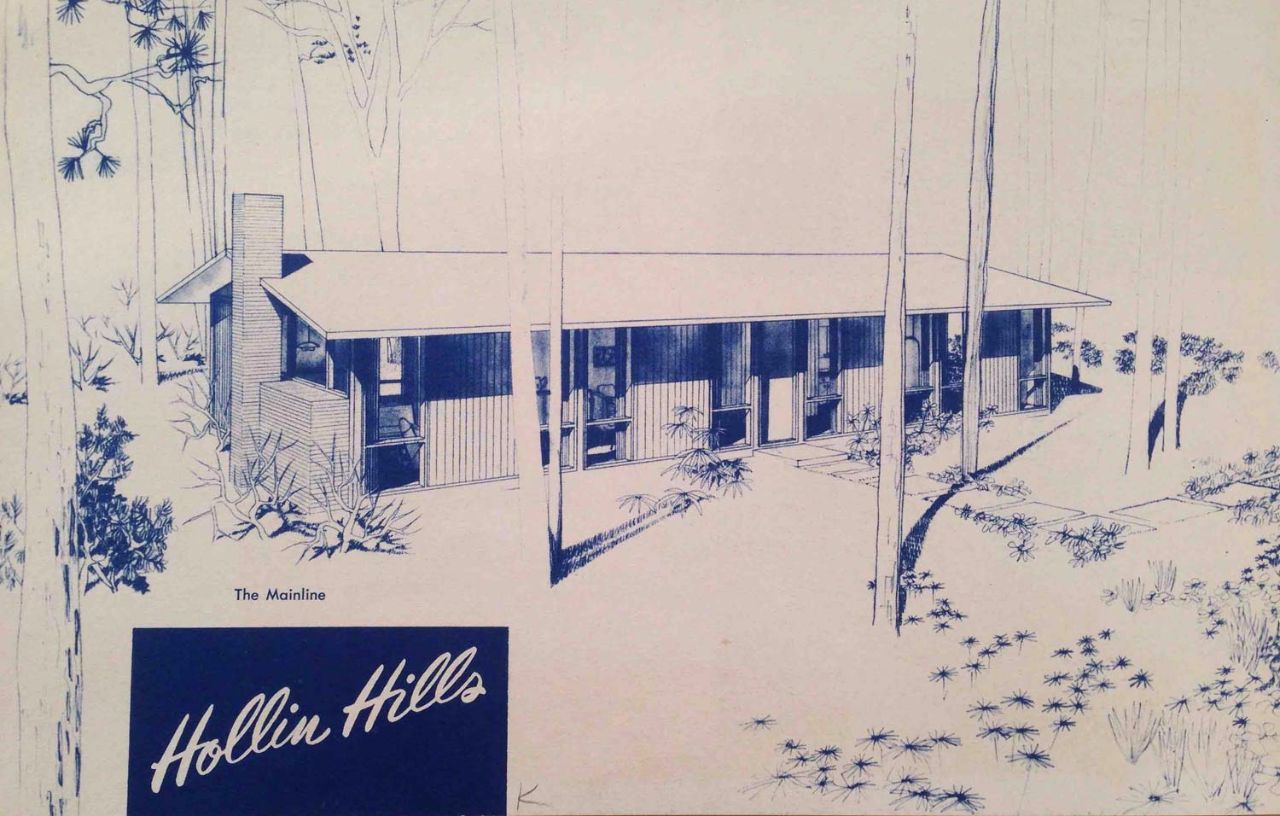

Advertised with blueprint drawings to play up its architectural kudos, the Mainline was one of three new designs for 1957, boasting ‘dramatic design’ and ‘a contemporary use of glass add to the essential spaciousness’.

I read through every issue of the community newsletter, and put together patterns. Each month people leave for foreign postings. The Coffins go to London; the Silvers to Manila after jobs in Paris, Rome and Iran; Richard Barry and his family returned from Bangkok where he was the assistant attaché. That same month, Alan Little of Martha’s Road, just a few streets from us, testified before a Marine Court about ‘communist mind warping techniques,’ the newsletter reports. ‘Dr. Little described the Red methods of brain conditioning, which combine mental torture and intense indoctrination – he is with the Foreign Service Institute staff and has done extensive research on Russian propaganda techniques.’

In the mimeographed pages I also find mentions of foreign visitors: Yugoslav military officers in November 1952. The Economic Cooperation Administration, the government agency administering the Marshall Plan, brought over French builders, Austrians, Norwegians and Swedes. Someone left Hollin Hills for the Ford Foundation – one of the charitable groups funneling CIA money to literary magazines and MoMA. The same month my parents move in, families leave for Germany, London and Indonesia. I could go on.

This is not the community I recognize. This is not peace, not leftist protests, or the promise of progressive politics. This is something else entirely. We were spies.

I’m sure something of this past haunts the place and its values, haunts my values, my community. This is American exceptionalism, the city on the hill, my community in its earliest days. It’s a place where hopes to change the world became bound up with national power.

*

At a neighborhood picnic, I stand in one of the community parks near a stream where I used to catch minnows as a kid. I stare at the water, beer in hand. The smell of grilling hot dogs wafts in the air, and a man with thinning hair is next to me. I tell him about the minnows.

‘You grew up here?’ he says as if I were a rare species. He’d never let his children play in the stream, or rather he clarifies, his wife wouldn’t.

My mother has been out of the hospital now for two days. I cut through neighbors’ yards to the picnic with my sister and her boyfriend, and we talk about how strange it feels to trespass. That is the word we now use, ‘trespass.’ We walk down a neighbor’s driveway. Our steps crunch on the gravel. Ellen asks if they’re home as she slides past a hedge. I hold my breath. We’re close to the door. When we’re back on the street again, Roger says he’d always walked this way to school when he was little but it feels awkward now. Some new people, he explains, have even put up posted signs announcing their property is private.

That night I ask my mom about the CIA. ‘Really?’ She says. ‘Here? In Hollin Hills? I don’t believe that.’

‘But, how would you know,’ I say. ‘That defeats the purpose of being a spy.’

She says that she knows Roger’s dad was, well she knows now.

‘Do you think maybe Dad could have been?’ I look at her. The question has been hanging over me. He was a good person. I have files of letters thanking him for work in villages in the Philippines and photos of him when the lights first went on in a rural town in Nicaragua. He was there too in the White House as Presidents Kennedy and then Johnson signed agreements to build rural electric co-ops in underdeveloped countries. But the pieces fit.

I’m not sure how knowing the answer might change my image of him. I tell my mother about the talk with Michael Sorkin and the letter in the Washingtonian and all the people I’ve discovered who were spies.

She’s emphatic. ‘No, never.’ Her robe is covered with wisteria flowers, and the coffee table next to her has books piled on it to read for her two book clubs.

‘But how would you know?’ I repeat. ‘Those international programs, all that travel, Africa and USAID in the 60s? The Philippines in the early 70s when the US is most worried about East Asia?’

She remembers a couple people who’d worked under my father and had been in the CIA before. Michael Sorkin said that when he was growing up there were people in the neighborhood who’d just say they worked ‘for the government,’ as if ‘government’ alone was code for spy. I tell my mother this and ask about my dad again.

‘I’m not sure,’ she says, ‘not when you put it like that. I don’t know.’

And I will probably never have the answer, either.

*

I circle my mother’s house and think about how the bricks that cut through both floors, heart and hearth of the home, are part of me. The developer bought the bricks from old warehouses being torn down nearby in Alexandria. In 1957 LIFE magazine had called them a ‘comfort.’ They are to me. The patterns in them feel like they’re imprinted on my skin and cells.

Downstairs are three that I colored with blue crayon. My mother was livid. I just wanted them to match the others that I realize now had been part of a hand-painted sign. Hints of those pasts haunt the home. These details swell. Doubts and questions loop. What had my father been doing overseas in countries that loomed large in our fears of communism. I have pictures of him with Imelda Marcos. There had even been co-ops in Vietnam he’d consulted on during the war and were financed by the US with counter insurgency money.

Now I am building a house based on this one. Will it feel like a home, and what does that word even mean? As I talked to my mother and her neighbors, I realize that the original ‘pioneers’ of Hollin Hills had been moving towards something that looked like the future. Instead I’m rebuilding the past. I don’t want to give up on modernism’s values no matter what else is smuggled in with that way of thinking. My modernism was about committing to a better world, not to democracy-building or exporting American values or espionage. The CIA doesn’t fit my picture of the place I grew up. I want an architecture that’s committed to fixing social issues even if that is the fairytale, only I’ve found here something muddled and muddied. I wonder as well whether losing the idea that things have meaning, that our choices, even down to the one as small as our cutlery, can change us, is too much for me to sacrifice.

I pull out the copy of the New York Times Magazine Arnold Edelman had given me. The ad he’d been looking for wasn’t for real estate but private banking. In it a penthouse is a fugue of beige. A couple smiles. There’s a fireplace and dozens of candles, all lit—and two Hans Wegner rope chairs. Unused, they face the room like sculptures. ‘Two truths:’ the ad promises,’1) most wealth mangers don’t actually manage your money, and 2) we’re not like most wealth managers.’ If I’m ‘ready,’ the copy says, ‘maybe it’s time we spoke.’ The ‘we’ is BNY Mellon Wealth Management, the bank formed from the merger of Alexander Hamilton’s Bank of New York and the Mellon dynasty’s firm. How did that rope chair end up as a symbol for wealth in an ad? In a way it makes sense. In the fifties modernism became tied to a certain image of America, a visual and artistic weapon in an ideological war, and now its clean lines are being used to sell investor advice. As a symbol modernism has proved itself maleable, but I didn’t see it that way. I believed in its progressive possibilities.

Creased and folded on my desk since Arnold Edelman handed it to me, this ad with its Wenger chairs ran on page five in the New York Times Magazine, 12 July 2015.

Those chairs were cheap and meant to be stowed away and designed for everyone are now reduced to markers of status. That they were affordable was exactly the point. It wasn’t about the chair itself, just like it wasn’t about the stuff, not the sofa or knife and fork but the values inherent in those things. The beliefs were almost Kantian. The ethos was part of the aesthetics, the form was in the function. They were inseparable. That rationality was modernism, and it was the last gasp of the Enlightenment.

This was what Arnold Edelman had been trying to say as he handed me the magazine at his door. A chair wasn’t simply something for sitting in but more. The intentions mattered. It wasn’t just the actions alone but the ideas behind them. These are the values I’ve been trying to articulate. Now I realize I’ve been searching for some moral rigidity in things. My modernism—the simplicity, the honesty—comes with ethical overtones.

Yet, there’s the fact that the intentions and actions of people who lived in Hollin Hills didn’t always match up. Many of them had been spies. They also tried to improve the world like Arnold Edelman and Tom Fina and my dad. My father would talk to me about empowering people to control their own resources. He did empower those people; he made material changes in their lives, but I wonder too what else he might have done? I keep thinking of that word ‘honesty.’ It was used to describe the furniture’s values, but here in Hollin Hills behind the honesty and openness was something much more covert. How did spying and honesty marry so well?

I walk the narrow streets, take paths through the woods. Rays of light pierce the trees. Here is utopia, but that utopia was a cold war.

Modernism was the last universalizing movement. The dream was that it was democratic, that it was for all. Anything that is for all, however, is not just universalizing but totalizing. It imposes a view of how life should be lived. Dictates were inherent in the designs. There was one style for everyone. Now truth is individual, and it is easy to see how quickly imposed values go wrong.

In the US modernism was embraced by corporate culture and the rich, and was forced on the poor. The wealthy built custom homes; the poor got shoved into housing projects. Corporations got glass and steel headquarters in the International Style, which came off as vast and impersonal, because, of course, those companies were. And, Hollin Hills was a dead-end. Literally, it was built on cul-de-sacs. Here we had the democratic urge to create something for everyone, while officials like President Eisenhower and Hollin Hills’ own architect Goodman proclaimed the individual. The community was tied to modernism’s aesthetics and those aesthetics became easy to adapt to the Cold War and American values. Now I’m left trying to understand where my father fits in all this. In the 60s he sent telegrams to the White House and Attorney General after the police brutally attacked civil rights protesters, and in the 50s he wrote Adlai Stevenson about his fears over what America might become after Stevenson lost to Eisenhower. My dad believed in change; he was progressive, and he might have been a spy.

These are the contradictions I’m still trying to parse.

Photographs courtesy of the author.