Last month, a plastic surgeon in Buenos Aires tried to seduce me. He was perfectly handsome and bronzed, with wavy hair and a Byronic shirt open at the chest to reveal a medallion featuring Michelangelo’s David. He’d invited me to his apartment for lunch. We drank red wine out of crystal-cut glasses, and he put on a DVD of a modern tango ballet which featured homoerotic scenes, for example a half-naked male dancer ‘tangoing’ with a long-legged table. All of the above led me to assume that he was gay – until he put his hand in a place that suddenly made me reconsider.

What I should have spotted straight away about this surgeon’s appearance and tastes was not his sexuality, but the fact that he worshipped physical perfection. Like almost everyone, I am extremely imperfect, so I shouldn’t have been surprised when he tried another tack.

‘I’ll give you a skin consultation,’ he declared, and I found myself in his consulting room, a bright light shining in my face. It’s not every day you get the chance to star in your own Botox soap opera.

‘Your face is perfect,’ he concluded.

‘Really?’ I said, strangely disappointed. ‘But what about these lines on my forehead, and these frown marks…’

‘No,’ he said and switched off the lamp. ‘I’m telling you, you are perfect.’ And he put his hand in the same place again.

He seemed genuinely hurt when I fled through the gilded lobby under the gaze of anatomically correct cherubs. The look on his face said, ‘I tell you that you’re perfect, and you’re still not impressed?’

*

The point here dear reader, is not to discuss dermatology. Nor is it to mock the friendly surgeon for trying it on with his lunch guest – after all, he put on a good show. The point is that he had sincerely meant ‘perfection’ as the ultimate compliment, and I had been sincerely disappointed. Why? Because in his world, the pursuit of perfection is the currency which has made him rich and his clients happy.

But his world is not my world. I always thought there was something wrong with the likes of Arnold Schwarzenegger, for instance. He looks too much like the idea of a perfect man, rather than an actual man. As Clive James put it once, he looks like ‘a brown condom filled with walnuts’.

There is something to be said about aliveness in all this. The opposite of attraction is repulsion, and they are both active states. I’m no stranger to the kind of physical attraction that turns your brain to pulp in thirty seconds, and I know that when we are physically attracted to someone, our desire feels alive, sometimes violently so. The person I desire has something that moves me (preferably in his direction). I could never feel neutral towards him. He may not have wavy hair and a perfect tan, but he will be marked with a particular, unrepeatable beauty – a crooked tooth in his smile, perhaps, or asymmetrical eyebrows. The air around him hums with the thrilling electricity of his being in the world as he is. Not as someone imagined him, or pumped him up in a gym, or modelled him with a scalpel.

What is beauty? In her study on beauty and attractiveness, Survival of the Prettiest, the American psychologist Nancy Etcoff argues that beauty may well be in the eye of the beholder – but that’s one biased, biological, big collective eye. In fact, we are all hard-wired to desire a certain range of facial and body features, regardless of our cultural make-up. Small chins, full lips, and lustrous hair are always attractive in women, studies show, just as a well-defined jaw and wide shoulders are always attractive in men. It’s something to do with oestrogen and testosterone, and other complex biological phenomena. But hear this: even male babies respond more warmly towards women who are judged attractive by this set of features, and you can argue with psychologists but you can’t argue with babies.

So, does that tell me what beauty is? No. With or without the full lips and the broad shoulders, in practice we all recognize it when we see it, and react to it with the most important parts of ourselves – our guts and our imaginations.

We also recognise what beauty isn’t, and this is why Mr Toledano’s photographs of surgically perfected people are so brilliantly disturbing.

The first thing I felt when I looked at these beings was a clinical chill, as if I was in Doctor Moreau’s lab where things had gone horribly wrong. As if, but not quite – because in fact, things here have gone horribly right.

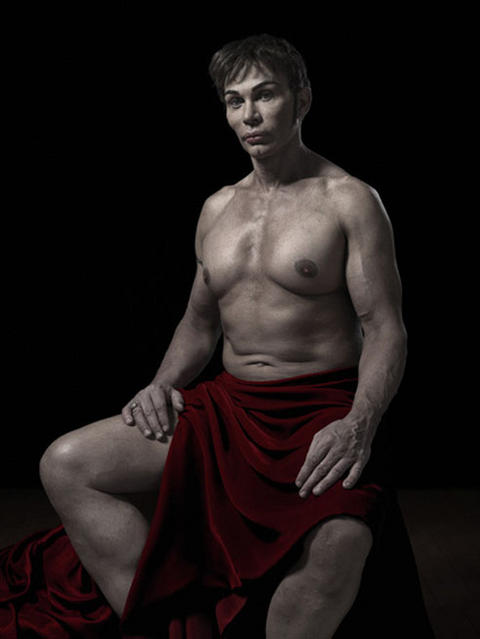

We are in a world of anatomical hyperbole here. The breasts are too breasty. The lips are too labial, the cheekbones too sculpted. The eyebrows are too arched and the muscles are too brawny. I look hard, but can’t find anything personal in these persons to remember them with. They are specimens preserved in the museum of their own desire. They are the offspring of a bank account coupled with a tragic misunderstanding, more on which in a moment.

Unlike most of us, with our flawed faces and bodies moulded by the passage of time, ‘Steve’ and ‘Gina’ are moulded by the surgeon’s hand. Their primary sexual characteristics are so hyper-real that they tip over into sexual ambiguity. It is the extremeness of Steve’s masculinity that makes him suspect as a man. It’s the over-planned positioning of Gina’s breast swellings that makes her look so unlike a woman.

Apart from their medical history, these bodies don’t tell any story – because the past has been wiped away. There is nothing left to the imagination here, because they are already imagined. In this sense, they are pornographic. As with the bodies in pornography, where we know exactly what is going to happen, nothing is at stake here, because we know exactly what has happened. The result is an anti-climax. Despite the frantic action, pornography is static. Despite all the perfectly pert swellings on these bodies, they are strangely inert. Instead of suspense, there’s silicone.

But then I look at the eyes, and I see something startling. I see the story behind the blank flesh. The precise point where the pornography of desire turns to Faustian metaphysics. And this is Mr Toledano’s artistic achievement. Steve’s, Gina’s, and the other models’ eyes are the only remaining place that expresses something personal about them. What I read in them is in turn defiance, pride, hope, sadness, fear, loneliness, and a desperate plea. In other words, the stuff you can find in most people’s eyes; but most people’s eyes don’t sit on top of bodies that have been sliced and stitched so much in order to become themselves.

‘Please,’ they say, ‘Please desire me. Please fantasise about me. Please admire me. And please, finally, consume me.’ To hear yourself say No to this plea – as you inevitably will, unless you’re a pervert – is sad. So much hope, so much self-hate, and so much silicone have gone into these creations. The stakes are, in fact, exceedingly high, and the overall impact of these photos is one of deep existential sadness. Creatureliness is, alas, not sexy, unless you’re in Avatar.

*

Remember the moment when Faust finally achieves perfect happiness, and therefore perfect stasis? That is also the moment he gives the Devil access to his soul, according to their devilish pact, and instantly surrenders his mortality and his humanity. This is what is happening here – the moment of unnatural perfection is not the moment when you become yourself. It’s when you stop being yourself. If nothing can touch you, not even time, what chance is there that a human hand will want to do it?

This is why, my dear surgeon, perfection is not a compliment. It’s a diagnosis for which there is no treatment. It’s engineered in the mortician’s lab, where cosmetic surgeons dwell.

Surely you know – from the medallion around your neck – that the point about Michelangelo’s David is not that he is perfect. The point is that – five centuries on – he is still inimitably, naturally, adorably human.

Both photos © Mr Toledano, from www.mrtoledano.com