On October 31 it was still hot and that’s when I saw Xu for the first time. At the Poxx, a club for Westerners in the heart of the French Concession. It was 10 p.m. I’d graded homework till late and was starving, and by the time I went out I found all the food places closed. After walking around for half an hour I noticed a fuchsia neon sign between two yellowed trees. I didn’t know the place. I just thought fuchsia signs were for non-Chinese spots, and non-Chinese spots often stayed open late. Going down the escalator from Wuyuan Lu, symbolically you left China. At the bottom, it was pure, blinding Occident. China bleached until it became Europe.

On the raucous square there were Irish pubs and cocktail bars and dark dance clubs with flashing lights. Every locale had a glamorous veneer, like the white people inside them standing around drinking, skinny and self-assured, with glossy lips and easy laughter. I would learn many things there. To get so jealous my legs shook. To drink quantities of sake hard for one stomach to handle. To laugh for a long time. To take care of someone without expecting anything in return, the way you do with plants. To hate Xu’s friends. To tolerate Xu’s friends. To fall in love, by accident, the way you hit on a religious channel while looking for something to watch on television.

I chose the Poxx because it glowed. It glowed brighter than all the other places combined, especially once you were inside. An alarm-blue light, like an emergency room. There were girls dressed as possessed nuns and characters out of Stephen King. It was Halloween, even in China. Maybe even more so. I sat at a corner table and ordered some prawns. I ate, watching the clown from It projected on the back wall. The clown appeared and disappeared in the light. Then I saw her. At a table off to the side, alone. Dressed as a fox. The one from Chinese folklore that turns into a woman to seduce gullible, needy men. I vaguely remembered the stories. My brother had told them to me.

It’s not true that I remembered them vaguely. I remembered them well. Better than stories I had discovered on my own. Tales about delicate, submissive women who pretended to want love but actually wanted something darker. They had pointy nails and eyes that flickered in candlelight. There was always a moment of revelation. A moment in which the two images – the wicked fox and the amorous woman – no longer coincided, their edges separating like a deck of cards thrown on the floor. And then the irrevocable happened.

The girl took off her mask. A pale and angular face, hair a black bob. Pretty, I thought. I’d been on anti-depressants for six months and everything seemed interesting. She started looking at me. Staring. As if she could read everything in my head. What I loved, what I hated, the idiocies I said to myself in the mirror sometimes like I’d seen people do on TV. YOU ARE A FORCE OF NATURE. DON’T GIVE UP. YOU WILL GET WHAT YOU WANT. The useless things that accrue in the mind over the course of a life. Sayings, platitudes. The things Ruben said to me the last day of his life that I’d tried not to memorize. You can keep my piano . . . Don’t ruin it . . . Tune it once in a while . . . Fix the windows in your room, they let in too much cold . . .

She came over. She sat down on the edge of the stool next to mine. From up close she had full lips and a lanky frame, like something out of a magazine. I couldn’t believe she had really come up to me.

‘Are you Russian?’

‘No.’

‘German, then.’

‘Nope.’

‘English. You’re English, that’s it. I’d like to go to England, it always rains, I love the rain. When it rains I watch bad movies and eat junk. But I like it, it’s a way to be alone, to think. Do you like this club? And China, do you like China?’

Behind that avalanche of English words nothing seemed to move. Her tone was calm and cool. I answered by nodding yes and no, like a little girl being questioned by the police in the middle of the night.

‘How are those prawns? Fresh?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘Boring! Why don’t you want to talk to me?’

I was frozen. I was frozen but the world demanded some sort of reaction. The world was an incredible girl asking me banal questions. Maybe that’s always the way the world shows up.

‘Well? Anybody in there? What are you thinking about?’

‘My brother Ruben is dead.’

It was the first thing that came to mind. For a long time it’d been the first thing that came to mind, always, no matter the context. Saying it over and over had made it lose some of its magnitude.

‘Huh? Did he die today? Are you serious? My god!’

‘No, no. Months ago.’

‘Oh. So why bring it up now?’

‘No reason. I don’t know why I said that.’

‘Maybe because you feel like you want to tell me everything. That’s a good thing.’

‘No. It’s not that. I actually say it all the time. Yesterday I told a girl eating ice cream on the street.’

‘What did she say?’

‘Nothing. I said it in Italian. Of course she didn’t understand. I do it a lot, really. The last time in Rome, I told a telemarketer.’

She laughed. Her laugh sounded nice. It didn’t offend me that she laughed at me. At my awkward way of handling my grief.

‘You’re funny. You should talk more.’

‘When I talk more, I stop being funny and become . . . unsociable.’

‘I can see that. You are unsociable. You’re unsociable and have blonde hair. And your eyes . . . They’re brown, I think. Or green.’

‘I don’t know. Brown. But when I cry, they turn gray.’

‘Do you cry a lot?’

‘Only when necessary.’

‘I’m going to try and make you cry so I can see them change.’

‘I’d rather you not.’

‘Tell me something else about yourself.’ She folded her hands under her chin.

‘What do you want to know?’

‘Do you like me?’

‘Uh . . . You’re so direct.’

‘I’m Chinese. We don’t waste time. Don’t you know how fast we can build a hospital?’

She laughed again. It was a laugh full of attention toward me. I couldn’t tell what kind of attention. Maybe genuine interest. Or maybe a cynical fascination. Like a child watching ants carrying food only to reach out suddenly and squash them. No matter. Either way was fine. I decided to laugh too.

She was waiting for an answer. I stopped laughing. I chewed my food, took my time. My heart was pounding uncomfortably, and she knew it. She read my discomfort, my excitement. I never would have thought I could feel a physical attraction so strong it could be detected, like a wolf sensing a person’s fear. She took my wrist. Behind her there was an aquarium full of turtles with pointy, leathery heads. A waiter went over and chose one for slaughter.

‘Want to get a room with me?’ I coughed in surprise.

I peeled the last prawn.

I picked it up with my chopsticks and put it in my mouth, rubbery and limp. I envied it because it didn’t have to decide whether or not to follow a strange and stupendous girl.

‘Okay, let’s go.’

The taxi sped through the deserted, rain-bruised streets with stomach-churning technique. It accelerated and braked jerkily as the night around us thickened, swallowing up the closed shops and blue skyscrapers, their pinnacles like knife tips. I had an unpleasant sensation as if everything – the downpour, the blue, the arched concrete bridges, the abrupt lunges of the clutch – were coming into my head and getting stuck there. Through the windows, trails poured off the traffic lights.

Fox talked nonstop. She talked about all kinds of things, animatedly, as the dark city rushed by behind the glass. Her English was pretty good. When she came up against something she didn’t know how to say, she fell silent and her face scrunched up until another concept surfaced. She talked about clothes and lip gloss, respiratory ailments caused by pollution, so common in Shanghai, and how if you have one you should never eat seaweed. She said she’d never seen any stray cats in Shanghai. ‘Where are the cats?’ she asked. I couldn’t really listen; I just wanted to follow the flow of those phrases, be struck by that sound coming from her throat, that emerged from her body just for me. I’d never had such a physical interest in language.

The taxi stopped. I looked at my watch: it was three – how could it already be three? For a second I asked myself whether it was Italian time, a question that made no sense. As I stepped out on to the dark street, and she handed her phone to the driver to pay, I touched my face to find a tear.

We were in Pudong. The financial center of Shanghai. A new district, made of cold skyscrapers and shopping malls, merging into one other, identical and bright like hospital wards. A district calculated to demonstrate something, the idea of an aseptic, redemptive, to-be-completed future. We climbed a ramp of stairs; we walked in a circle suspended over the sleeping city, the blue and red rocket-shaped high-rises, the occasional car zooming past, the loudspeakers issuing the same minute of tired classical music over and over. The ramps of stairs were numerous and concentric, so geometric they hurt the imagination. On one ramp, an American supermarket shone in the dark where the moon should be. Fox took my hand and said: ‘I like you too much. I don’t know, maybe it’s fate. But it’s not normal.’

Before, it was all rice fields, here in Pudong. Miles of golden fields, the kind you see in movies with long takes and farm workers with sunburnt faces. Now it was the area with the tallest buildings after Dubai. The transformation had been rapid and ostentatious. Eradicating everything, reaching into the heavens with glass and steel, reaching like a demon pleading for light. Now the buildings contained newspaper offices, multinational corporations, TV stations – economic paradise. An erratic accumulation of restaurants and coffee shops and 3D movie theaters. When almost everything was turned off, at night, like that night with Fox, it seemed like the future was holding its breath, waiting, waiting to show you that everything was going to be all right.

We entered a tunnel which led to a shopping center, all the stores closed, and then let out on to a street, bordered by iron railings. We kept on walking, holding hands, lost in the music, which waned on the high notes and then picked up again, formulaically upbeat. She told me about M50, a renovated industrial area. It used to be a complex of factories and warehouses called Chunming, and now it housed over a hundred art galleries. I listened to her and asked her precise, thoughtful questions. I thought it was just chit-chat. But she was laying out the geography of our entire relationship. A relationship that had to be planned like a pilgrimage. Like the Japanese in the seventeenth century: lovers who were disillusioned by life and the impossibility of their passion planned a journey that would culminate in a double suicide called shinju: literally, ‘in the heart.’

We got to the hotel. Fox paid at an automated kiosk. I watched her from behind, her shiny bob and her hand typing across the screen. I felt hazy and happy. Perhaps happiness was this: the blurring of borders. No one was at reception. The lobby had a vending machine with instant noodles and lubricant. We waited an eternity for the elevator. I said something I forgot as soon as I’d said it. The paint on the thirty-first floor was peeling off like a scab.

She went into the room and sat on the edge of the bed. ‘How did your brother die?’

‘What?’

‘You heard me. Answer.’

I was standing next to the wardrobe, an unpleasant and imposing wardrobe, and I wanted to get this subject out of the way and at the same time talk about it endlessly: since Ruben had been gone there was this messy jumble in my head of my thoughts and thoughts I believed to be his. It was difficult to separate them, difficult to determine which ones I could identify as my own.

‘Well?’

‘He was born with it. A heart defect. It was the biggest difference between us.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘We were twins. But our eyes were different too, his were blue. And this . . .’

I ran a finger around my cheeks: Ruben’s were serious, strong; mine were round and rosy like a young girl’s.

‘See, I look like a little girl.’

‘That’s a good thing. That’s the only time in life when we’re beautiful. When we’re young and don’t hate anyone.’

‘I don’t know about that. Children can hate, for sure.’ Her face went cold.

‘That’s not real hate. It’s just love in reverse. It can be turned the right way in an instant, with a word. It’s just that usually parents don’t want to say it.’

‘What is it?’

‘What?’

‘The right word . . .’

She didn’t answer. She slipped off her shoes, black wedges shiny like a polished weapon.

I felt an urge to leave. Leave and forget this girl, curl up in bed and do something painless. Watch a show, grade my students’ work. I knew that being with Fox wasn’t going to be painless. But I sat down beside her and placed a hand on her thigh. The same hand that she had grabbed suddenly in the street and held all the way to the hotel: a hand that had absorbed a kind of promise. When I touched her, I felt a shock.

She turned to me abruptly with a wide, maniacal smile. ‘Ma davvero non ti ricordi di me?’ she asked. My heart pounded in my chest. The lights were too vivid. Her eyelids batted the way flies flit around food.

‘I don’t understand. You speak Italian? Who are you?’

‘I’m one of your students.’

‘One of my students?’

‘That’s what I said.’

‘I don’t have a good memory for faces.’

‘I remember you perfectly.’

‘Why are you only telling me this now?’

‘It was fun messing with you. Don’t look at me like that! You’re so funny when you’re mad . . .’

She laughed. Her voice, in Italian, was grotesquely authoritative, like that of a cartoon witch.

‘I don’t understand why you lied to me.’

‘Lied, that’s going a bit far! Don’t be so dramatic. I wanted to talk to you without you being in a position of superiority, as a teacher.’

‘But . . .’

‘You know what I mean. Like someone who’s supposed to teach me something . . .’

‘I don’t think I have anything to teach anyone. I mean, besides Italian.’

‘Does that seem like a small thing to you? Teaching people to think in another language?’

‘I guess not. I’m sorry I didn’t recognize you. You didn’t talk in class yesterday. That must be why you didn’t leave an impression.’

‘Says the girl who never talks!’

‘Exactly. I don’t leave an impression either . . .’

She laughed again, sweetly this time. She took off her earrings and tossed them on the nightstand. My perception of her changed from one second to the next: cute and then mean, then cute, then mean, then radiant and hollow like the high-rises out the window. My hand was still on her thigh. It was a different hand, now. Different from a few hours ago. Too pink on her white skin, like something burning.

‘Now take off your clothes.’

I jumped to my feet. She dropped her phone on the bed.

‘What? No. I’m not ready.’

‘I don’t mean to fuck.’

‘For what then?’

‘I can’t explain. It’s an honesty thing. No secrets.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘It doesn’t matter. Take off your clothes or I’m going and leaving you here.’

The sweetness was gone. I didn’t have time to miss it; I had to undress fast or risk abandonment.

I undid the top button on my shirt. My hands trembled.

‘No. Skirt first. Then the rest. There, good girl.’

I kicked my shoes away. They flipped over on the rug. On one of the soles what looked like a drop of dried blood was just a crushed flower. Off went my skirt and then my cotton panties and my blouse. My bra. Fox smiled as she eyed my fleshy thighs, my little paunch, the serrated line under my navel from the elastic. She smiled as she commanded, because she knew my mind was as soft as my body.

‘I used to be thinner. Before . . .’

‘I know. You look good. This is how little girls should look.’

‘I’m not a little girl,’ I said in a minute, shrill voice, maybe the voice I had in nursery school. She started to undress too. She slipped off her latex leggings and jacket and satin corset top. She had an expanse of opaque white skin like the amniotic sac surrounding the bodies of newborns. The stagnant light from the wall lamp, the too high watts, revealed skin without a single mole or blemish. Nothing but milky perfection. I approached the bed. I thought of the word love and felt embarrassed.

‘What’s the last book you read?’ she asked, unhooking her bra. I tried to remember, but all that came to mind was a red cover and words crowding the page like ants.

It was as if my life were suddenly shedding details to make room for new ones.

‘I don’t know. I’m sorry. I can’t remember.’

‘Don’t worry. Just making conversation.’

‘You haven’t told me your name . . .’

‘Xu. My name is Xu. What’s yours?’

‘Ruben.’

‘Wasn’t that your brother’s name?’

‘Yes. Now it’s mine.’

Xu. All I wanted was to look at Xu and be looked at by Xu. Be touched by Xu. Be commanded by Xu. Being with Xu made my thoughts absolute. Free of nuance. Like a desert at high noon. We lay next to each other. On the Day-Glo orchid duvet, under the stream of A/C. I couldn’t stop looking at her. The light, on the basil-green walls, was acidic and insistent. Actually, we weren’t right next to each other. There was room for a third body between us. For an instant I imagined it was Ruben’s body there.

She talked all night. Without touching me. She didn’t want to touch me. I didn’t want to touch her. Anything more physical than words would have killed us.

‘I’ve had all kinds of jobs. Shit jobs. I just wanted to get away from home.’

‘I know what you mean.’

‘I started at fourteen. Working, I mean. I cleaned stairwells. I’d eat fried frogs at the place next to school and then go to work. I never slacked off, because I knew there were video cameras. There are billions of video cameras in Shanghai, it makes you start acting like a reality star. If you know you’re always being watched, you stop being yourself. You become the way others want you to be, you know? While I cleaned the stairs I’d make faces, blow kisses, wiggle my ass the way they like.’

‘They who?’

She looked at me, perplexed. Later I would learn that to Xu ‘they’ was a generic entity not to be scrutinized. To do so would be too distressing.

‘But I had short hair and it didn’t look good. I dressed like a boy. So I grew out my hair. I bought tight tops and fishnets. I did some modeling for makeup and lingerie companies. They liked my lips. My cheekbones. I was perfect. I was their little doll. Have you ever seen Molly? The doll they sell on every street in Shanghai? Like her. I was like her. But it didn’t last long. They couldn’t keep their hands to themselves. Little old men with glittering eyes and fast erections.’

‘And then what?’

‘The night of my nineteenth birthday, on a busy photo shoot, I met Azzurra. No one had remembered my birthday. No one. I’m saying this to explain how I felt. You do things for other people, you suppress parts of your personality, and then no one remembers when you came into the world. Might as well have stayed up in the heavens. Or wherever we are before we’re born. Know what I mean?’

‘Who’s Azzurra?’

She smiled.

‘She was a nice, very tall, forty-year-old clothing designer. I followed her to Milan but we fought constantly. I always felt hounded by her judgmental gaze. It’s a terrible feeling. It makes you stop being yourself. Like locking yourself up in a room. At least in Italy there are no video cameras. Not so many, at least. Shanghai has five billion, did I tell you that? Yet when a child disappears they’re never found . . .’

‘What happened with Azzurra?’

‘We broke up after two months. I found myself in a strange city with no connections . . .’

‘But you learned Italian perfectly. I mean, you sound like a native speaker. You don’t need to be taking my class.’

‘I know. I just signed up so I could practice. I didn’t know any Italians I could talk to here. Before you, anyway.’

‘But what happened afterward, in Milan?’

‘I found a job at a nursing home. I bathed the old people and reminded them of their grandchildren’s names. I reminded them which family members they loved and which ones they hated. I had all this power over them and I liked that. It gave me a reason to wake up in the morning. You know? If I wanted, I could have turned them against their own children, or anything.’

‘I hope you didn’t.’

‘You’re so moralistic. I know whether I did or not. I don’t have to pass some test of yours.’

‘Okay. Sorry.’

‘Every morning, the old women cried in the bath like little girls and the old men unbuttoned their pants and said obscene things to me. After two years in Italy I came back to Shanghai.’

‘In those two years you learned the language better than some Italians I know.’

She smiled. Her every smile drew me closer to an unbearable, electrifying place in my mind.

‘I’d already studied it before I met Azzurra, actually. I started with a cooking show I watched when I was younger, when I was sad. I don’t remember what it was called. There was a cute chef who made these amazing cakes, in every color. In the background you could see a garden, filled with sunshine . . .’

I looked outside: darkness and the countless nauseating lights in the street. The buildings that now appeared faded and metaphysical, the faintly glowing windows of empty offices, in a few hours would come to industrious, televisual life, made of money and data. Xu followed my gaze: who knows how it looked to her. She had grown up in that city, in that unrelenting darkness. Over all of it loomed the Oriental Pearl Tower: a red orb in steel lattice, topped by a tall obelisk. I had been inside there, one night. One of my first. I was lost. The tower looked like a toy and I found it reassuring. I went inside and took the high-speed elevator, my ears popping from the pressure. On top I walked across the glass floor and observed the distorted streetlamps, headlights. It was all so small, so irrelevant. The buildings steeped in darkness, the shopping malls in violent colors.

It was three, then four. After that quick rundown of her adult life she proceeded to the trivial. From her favorite brand of beef jerky to her tricks for winning mahjong. I had the feeling that she used words like wrapping paper: to cover other, more painful things. I couldn’t stop looking at her. Her unbelievable body. Her soft eyes, her perfect shoulders, the comma of her navel. Something didn’t add up. She wasn’t really naked. Nakedness is a wall. A mystery. It’s growing up and feeling shocked to see breasts emerging from your chest like soft bulbs from soil. But Xu felt no embarrassment, she had no imperfections. Nothing to be ashamed of, nothing that could be used to punish her.

At dawn, after that avalanche of words, she closed the curtains and brought back the darkness, the only thing that belonged to both of us. The curtains were somber and thick. They had an irritating geometric pattern, something like the plastic fencing used on balconies to keep cats from jumping off. I heaved a sigh: perhaps it was time. I’d never had sex with a woman and I wasn’t sure it would serve my happiness, but I really hoped it would. She was on her side, and I inched closer. I was trembling a little. The contours of her body cut into the dark like ominous mountains. In China, mountains are supernatural places. You climb them until you start to feel other things. See other things. The hermits of Mount Tai would bury themselves alive in damp narrow caves until reality burst open like a rotting fruit releasing its pulp. I kissed her. Her lips were ice-cold. The vent wheezed amid the slow sound of saliva and suction of tongues.

She broke away brusquely and resumed talking. As if nothing had happened. She just wanted to talk, talk until she’d exhausted something, what, I don’t know. She talked about tea leaves, how you have to pick them when they’re as delicate as a newborn’s hair. She talked about her family. She presented them like a family off a post-card, without nuance or interiority. People united by blood and a rudimentary love. Sharing meals, watching television together on the couch. Birthdays, holidays. Something about it was off, trying too hard to stick to the surface. Braces, anniversaries, a gray bunny an aunt and uncle gave her. Her voice rose and fell like the sea on the shore. She talked about her father. About his thick hair and his full and red lips like a rosebud. His collection of Mao statuettes. In brightly painted ceramic, lined up on the mantel. She had to clean them every Thursday when she was little, and she did it with her heart in her mouth, afraid of dropping them. She talked about all kinds of trips, exhaustingly long trips. To the suburbs, to the lush countryside nearby. To Lianhu Village to pick lotus flowers, which she would dry inside her Italian grammar books. To Beijing in winter, in the snow, on a tour, which, before Tiananmen Square, took them to a hotel room where they had to silently observe a sales demonstration for a knife set. A man with green eyes and Chinese features sharpened the knives, describing them melancholically like lost lovers, and then gave everybody one to take home. She kept hers for her entire adolescence, hidden in the linens. Every time she was sad or mad she would open the drawer and stroke it. Slowly, without cutting herself. Until she dozed off. Sometimes she woke up to find it next to her, under the covers. Missing in all her stories was her mother. She’d say ‘the three of us went’ but never mention her. She was a tacit presence, like passing time, like the ground we tread. Like air. Like smog. Behind the drawn curtains was the sun, the day, but we were in the dark, trapped in a primordial night, from which there was no way out except a colossal Big Bang.

I could have been more empathetic, pushed her to say more. Asked, What about your mother? Made her dig deeper. But I could hardly bear her communicative need, that deluge of information with only the occasional flicker of real feeling, taking all the attention from me. I wanted to be seen. Heard. For once in my life. I was repulsed by the feeling, but I couldn’t help it. My need for love battered my heart like a homely dog pawing at a door that never opens.

I went back to my spot on the other side of the bed. The rock-hard mattress pressed into my back. Everything was too cold and too clean. It was a bed in a hotel room, a place where nobody actually lives. ‘Are you okay?’ she said. I shook my head. I reached for her, but she got up and opened the curtains. Light flooded the room. It was day again. This time for real. It was eight in the morning. I had to go to work. The kiss had gotten lost in our conversation like a button between the folds of a couch.

Outside the windows you could see cars and pulsating traffic lights, without the audio. At that height, none of the street noise could be heard. Only the air vent. A low buzz replacing the sounds of life. Instead of car horns and engines and torrents of voices, a deep monotone hum: existence from above. The night up there had been soundless. Nothing but me and Xu. My breath, her voice. Now it was louder because it was morning and everything on the thirty-first floor was open. The nail salons, reception, accounting. I thought of iridescent fingernails in neat rows. Orderly lives. Xu put her clothes on and everything was back up and running.

I was first to leave. In the nail salon, a woman with pockmarks slept slumped over in a child-size chair in front of magazine ads taped to the wall. Turning right, I came to the reception of another hotel, an elegant man in the glow of a blue sign, and then to the sleeping pock-marked woman again, so I went the other way and this time it was the right direction. I sat on a couch and waited for the elevator. On a screen, indistinguishable girls danced in bridal gowns. Translucent skin, glacial eyes, cobalt-blue contacts. They sang ‘Ode to Joy’ in Chinese, their lips parted slightly, looking into the lens with blank conviction, surrounded by walls of lace and cream.

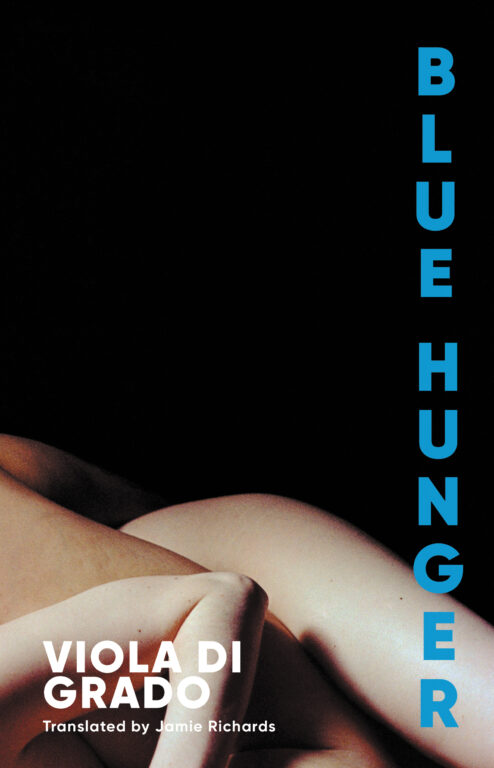

Image © Will Henderson