Once there was a young man who said to himself: this story about everybody having to die, that’s not for me. I’m going to find a place where nobody ever dies. And so he says goodbye to his parents and his family, and he sets off on a journey. And after several months, he meets an old man, with a beard down to his chest, trundling rocks in a wheelbarrow off a mountainside. And he says to the old man: Do you know that place where nobody ever dies?

The old man says: Stay with me, and you won’t die until I have carted away in my wheelbarrow all this mountain.

How long will that take?

Oh, at least a hundred years.

No, said the young man, I’m going to find that place where nobody ever dies.

He travels on, and he meets a second old man with a beard down to his waist. This old man is on the edge of a forest that seems to go on for ever and ever. And he’s cutting branches off a tree. The young man says: I’m looking for that place where nobody ever dies.

Stay with me, says the old man, and you won’t die until I’ve cut off the branches of every tree in this forest.

How long will that take?

At least two hundred years.

No. I’m going to find that place where nobody ever dies.

He meets a third old man with a beard down to his knees, and this old man is watching a duck drinking sea water from the ocean. Do you know that place where nobody ever dies?

And the old man answers: Stay with me and you won’t die until this duck has drunk the whole ocean.

How long will that take?

Oh, at least three hundred years, and who wants to live longer than that?

The young man went on. And he came to a castle. The door opened and there was an old man, with a beard reaching down to his toes. I’m looking for that place where nobody ever dies.

You’ve found it, replies the old man.

Can I come in?

Yes, I would be glad, very glad, of company . . . .

Time passes. And one day the young man says: You know, I’d like to go back – just for a moment, I won’t stay. I just want to go back to say hello to my parents and to see where I was born.

The old man says: Centuries have gone by, they’re all dead.

I’d still like to go back if only – if only to see the street where I was born.

So the old man says: All right, follow my instructions carefully. You go to the stable, you take my white horse, a horse as fast as the wind, and never get off him. If you get off that horse, you’ll die.

The young man mounts the horse and rides away. After a while he comes to the beach where the duck was drinking the sea. The sea bed is now as dry as a prairie. The horse stops at a little heap of white bones – all that is left of the old man with a beard down to his knees. How right I was not to stop here, says the young man to himself. And he goes on, and he comes to where he saw the forest. The forest is now pasture land – not a single tree is left. The young man goes on and comes to where the mountain was. The mountain is as flat as a plain. For the third time he says to himself: How right I was not to stop here!

Finally he arrives at the town where he was born. He recognizes – nothing. Everything has changed. He feels so lost, he decides to go back to the castle. One day on his return journey, towards nightfall, he sees a cart drawn by an ox. The cart is piled high with old, worn-out boots and shoes. As he passes, the carter cries out: Stop, stop! Please get down. Look, a wheel of my cart is stuck in the mud. I’m alone. Please help me.

The young man answers back: I’m in a hurry, I won’t stop and I can’t get off my horse.

The carter pleads: It will be dark in a moment, it’ll freeze tonight, I’m old and you’re young, please help me. So, out of pity, the young man gets off his horse. Before his second foot is out of the stirrup, the carter grasps him by the arm and says: Do you know who I am? I am Death. Look in the cart at all those boots and shoes I wore out chasing you! Now I have found you. Nobody ever escapes me . . . .

This story, first told centuries ago near Verona in Italy, can still speak to us. The inexorability of time, the inevitability of death, the desire for immortality – none of this has changed. Yet something has changed. The original listeners to the story would, I think, have attributed the young man’s vain and useless attempts to escape death to a lack of wisdom. They would have found in him a blindness to what was important, to what lay beyond the temporal. They would have seen him as a kind of opportunist. Today we would simply say the young man lacked realism. We see him not as an opportunist, but as a kind of dreamer.

The difference between the two understandings of the story is related, in part, to the decline of religious faith, but it is also related to a change in the way we approach the enigma of time. For the original listeners in Verona there lay, beyond the centuries which the young man cunningly acquired for himself, the domain of the timeless, of that which is outside or beyond time. For us the timeless does not exist; there is no place for it. Or at least no rational place.

Here is another story; it happened a little while ago in the next village. Jean, who works in the sawmill, lived with a woman whom he called Mother. She was about ten years older.

This woman had run away from her husband and children in the northern coal-fields, and had come to work as a servant in the local hotel. There, one morning, Jean noticed her because she was crying while picking beans in the vegetable garden behind the hotel kitchen. She said she couldn’t bear the thought of returning to the north – her husband beat her – could she stay with him in the village? She would cook for him.

She wore short dresses and had pretty legs. She cried and laughed unselfconsciously. Although fifty years old, she seemed, a little, as if she had just left school. He told her she could stay with him.

They lived together for four years and then she fell ill. She lost her memory. She could no longer pick beans or untie knots. If she went to the village, she couldn’t find her way home. She accused Jean of being unfaithful. She forgot to dress properly, and now it was Jean who cooked for her.

Eventually the doctors named her illness ‘premature senility’. To Jean it seemed that she was returning to childhood. Then they told him her blood pressure was too low, so she must be sent to hospital. He accompanied her.

Just slip away, the doctor at the hospital said to Jean, don’t let her know you are leaving.

When two days later he went back to the hospital to visit her, she was tear-stained and cowed like a prisoner. The specialist in his white coat behind an oak desk told Jean that her illness was incurable. There was nothing to be done. She would get worse and worse and the illness would kill her.

Jean pondered the matter for a long while. He thought about it when he was sawing wood, when he was sleeping in the bed they used to share. One day he announced: I’m going to fetch Mother on Saturday afternoon.

The young doctor on duty at the hospital refused to give his permission.

Who are you anyway? he asked Jean.

I’m the only person she has in the world.

You are not even a relative, and you’re not her husband.

I’m taking her away.

It’s I who give orders here! the doctor shouted.

No. About Mother you have no right. And you can listen to me. I’m taking her home.

Get out of my sight – both of you!

This is how the doctor admitted his defeat. Mother was the first to understand what this admission meant, and her whole face became radiant.

Jean took her back to the ward and dressed her. He put on her black stockings – although it was the month of June – because she said she wanted to look smart, now that she was free.

Are you hungry Maman? he asked her in the car.

It was like a prison inside there.

Don’t think about it.

They locked me in my room.

Don’t think about it.

They treated me so badly.

I’m taking you home, said Jean, and I’ve cooked us tripe for lunch.

I didn’t eat for a week.

We’ll eat some tripe and then you can sleep, Maman.

By the door of their house, the dog jumped up to lick her face. When she was in the armchair, one of the cats settled on her lap. Jean came into the kitchen with four tiny kittens, two in each hand. She took his hands and she rubbed the kittens against her cheek.

Jean! How happy we are!

Ah! Maman! Now we are all happy, he said, we are all happy! In this story Jean and his Mother live one Saturday afternoon as if the future did not exist. As if a Saturday were exempt from time. For all their difference of style, the two stories have something in common.

A need for what transcends time, or is mysteriously spared by time, is built into the very nature of the human mind and imagination.

Time is created by events. In an eventless universe there would be no time. Different events create different times. There is the galactic time of the stars; there is the geological time of mountains; there is the lifetime of a butterfly. There is no way of comparing these different times except by using a mathematical abstraction. It was man who invented this abstraction. He invented a regular ‘outside’ time into which everything more or less fitted. After that, he could, for example, organize a race between a tortoise and a hare and measure their performances using an abstract unit of time (minutes).

‘Time is not an empirical conception. For neither co-existence nor succession would be perceived by us, if the representation of time did not exist as a foundation a priori . . . . Time is nothing else but the form of the internal sense, that is, of the intuitions of self and of our internal state.’ Kant, Critique of Pure Reason.

A problem remains, however. Man himself constitutes two events. There is the event of his biological organism, and in this he is like either the tortoise or the hare. And there is the event of his consciousness. The time of his life-cycle and the time of his mind. The first time understands itself, which is why animals have no philosophical problems. The second time has been understood in different ways in different periods. It is the first task of any culture to propose an understanding of the time of consciousness: of the relation between past, present and future, realized as such.

The explanation offered by European culture of the nineteenth century – which for nearly two hundred years has marginalized most other explanations – is one which constructs a uniform, abstract, unilinear law of time which applies to everything that exists, including consciousness. Thus, the explanation whose task is to ‘explain’ the time of consciousness, treats that consciousness as if it were comparable to a grain of rice or an extinct sun. If European man has become a victim of his own positivism, the story starts here.

The truth is that man is always between two times. Hence the distinction made in all cultures, except our own, between body and soul. The soul is first, and above all, the locus of another time, distinct from that of the body.

‘I see,’ wrote Blake, ‘the past, present and future existing all at once before me.’

The great Lebanese poet Adonis writes:

Do you remember the house

ours alone

among the olive trees and the figs

with the source sleeping tight

against the orphans of the eye

Do you remember why the woods

beat their wings like butterflies

the earth’s first night . . . .

The night . . . .

Drill wells in your breast

be labyrinth and take me in

Everyone knows that stories are simplifications. To tell a story is to select. Only in this way can a story be given a form and so be preserved. If you tell a story about somebody you love, a curious thing happens. The storyteller is like a dressmaker cutting a pattern out of cloth. You cut from the cloth as fully and intelligently as possible. Inevitably there are narrow strips and awkward triangles which cannot be used – which have no place in the form of the story. Suddenly you realize it is those strips, those useless remnants, which you love most. Because the heart wants to retain all.

A dog barking shows

how threadbare is

the fabric of time.

Through the frayed repetition at dusk –

dogs were barking here

since the river was bridged

and the first dwellings built –

you can see

the centuries approaching

in single file.

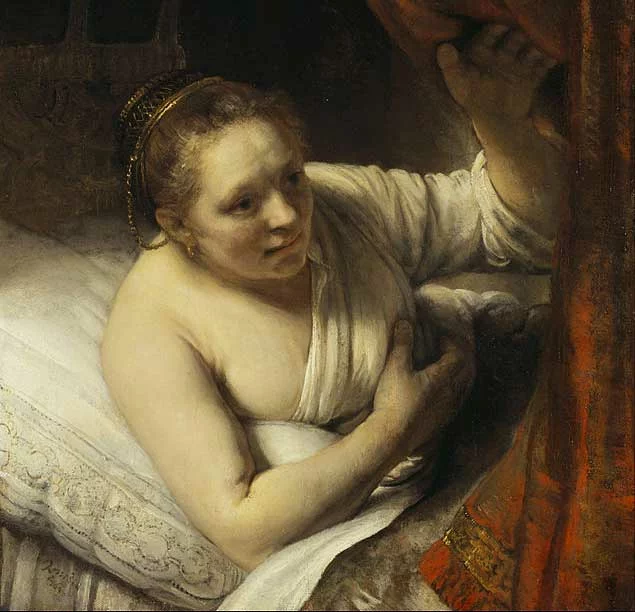

Rembrandt painted Hendrickje Stoeffels, who was the great love of his life, many times. One of his most modest paintings of her is, for me, one of the most mysterious. She is in bed. I reckon the picture was painted a little before the birth of Cornelia, Hendrickje’s daughter by Rembrandt. She and Rembrandt had lived together, as man and woman, for twenty years. In about two years time Rembrandt would be declared bankrupt. Ten years earlier, Hendrickje had come to work in his house as a nurse for his two-year-old son from his previous marriage. Hendrickje will die, although younger than Rembrandt, six years before him.

It is late at night; she has been waiting for him to come to bed. He has just entered the room. She lifts up the curtain of the bed with the back of her hand. The face of its palm is already making a gesture, preparatory to the act of touching his head or his shoulder, when he bends over her. In this portrait of Hendrickje she is entirely concentrated on Rembrandt’s sudden appearance. In her eyes we can read her portrait of him. The curtain she is holding up divides two kinds of time: the daytime of the daily struggle for survival, and the night-time of their bed.

Rembrandt must have painted the picture partly from memory, recalling the times he had come to bed late and Hendrickje had been waiting for him. To this degree it is a remembered image. Yet what it shows is a moment of anticipation – hers, and his by implication. They are about to leave the world of debts and monthly payments for the instantaneity of desire, or sleep or dreams.

The picture was painted three hundred years ago. We are looking at it today. There is such a tangle of times within this image that it is impossible to place the moment it represents. It resists the mechanism of clocks or calendars. I do not believe it is therefore less real.

The image of Hendrickje in bed was preserved thanks to Rembrandt’s art. Yet the need to preserve an image is felt by us all at certain moments.

There is a photograph by the great Hungarian photographer, André Kertesz, in which we see a mother with her child looking very intently at a soldier. We do not, I think, require the caption in order to know that the soldier is about to leave. The great-coat hung over his shoulder, his hat, the rifle, are evidence enough. And the fact that the woman has just walked out of a kitchen and will shortly return to it is indicated by her lack of outdoor clothes. Some of the drama of the moment is already there in the difference between the clothes the two are wearing. His for travelling, for sleeping out, for fighting; hers for staying at home.

The caption reads: A Red Hussar leaving, June 1919, Budapest. How much that caption means depends upon what one knows of Hungarian history. The Hapsburg monarchy had fallen the previous summer. The winter had been one of extreme shortages (especially of fuel in Budapest) and economic disintegration. Two months before, in March, the Socialist Republic of Councils had been declared, under Bela Kun. The western allies in Paris, afraid that the Russian and, now, the Hungarian example of revolution should spread throughout Eastern Europe and the Balkans, were planning to dismantle the new republic.

A blockade was already imposed. General Foch himself was planning the military invasion being carried out by Rumanian and Czech troops. On 13 June 1919, Clemenceau sent an ultimatum by telegram to Bela Kun, demanding a Hungarian military withdrawal, which would have left the Rumanians occupying the eastern third of their country. For another six weeks the Hungarian Red Army fought on but was finally overwhelmed. By August, Budapest was occupied. The first European fascist regime, under Horthy, had been established.

If we are looking at an image from the past and we want to relate it to ourselves, we need to know something of the history of that past. And so the above information is relevant to the reading of Kertesz’s photograph.

Everything in it is historical: the uniforms, the rifles, the corner by the Budapest railway station, the identity and biographies of all the people who are (or were) recognizable – even the size of the trees on the other side of the fence. Yet it also concerns a resistance to history: an opposition.

This opposition is not the consequence of the photographer having said, ‘Stop!’ It is not because the resultant static image is like a fixed post in a flowing river. We know that in a moment the soldier will turn his back and leave; we presume that he is the father of the child in the woman’s arms. The significance of the instant photographed is already claiming minutes, weeks, years. The opposition exists in the parting look between the man and the woman.

Their look, which crosses before our eyes, is holding in place what is: not specifically what is there around them outside the station, but what is their life, what are their lives. The woman and the soldier are looking at each other so that the image of what is shall remain for them. In this look their being is opposed to their history, even if we assume that this history is one that they accept or have chosen.

How close a parting is to a meeting!

Everywhere in the world people have invented stories about the Beginning, about how the universe was created. All mythologies are a way of coming to terms with the fact that man lives between two times. He is born and he dies like every other animal, yet he can imagine the origin and the end of everything. And as a result of this imagining, he lives with the eternal, with that which preceded time and will follow it, with that which is continually there behind time. The Red Hussar and his wife, like two people feeling their way round the furniture in a pitch-dark room, are looking for a door which opens on to what is behind time.

The Adams and Eves

continually expelled

and with what tenacity

returning at night!

Before,

when the two of them

did not count

and there were no months

no births and no music

their fingers were unnumbered.

Before,

when the two of them did not count

did they feel

a prickling behind the eyes

a thirst in the throat

for something other than

the perfume of infinite flowers

and the breath of immortal animals?

In their untrembling sleep

did the tips of their tongues

seek the bud of another taste

which was mortal and sweating?

Did they envy the longing

of those to come after the Fall?

Women and men still return

to live through the night

all that uncounted time.

And with the punctuality

of the first firing squad

the expulsion is at dawn.

Twenty years ago I saw a photo by Lucien Clergue, one of a series of photographs of a woman in the sea. For millennia, the look of a woman’s body in water has changed no more than the look of the waves. What we see in the photo must have been seen in the Egypt of the Pharaohs, in ancient China. Yet this changelessness represents only an instant when placed in the context of another ‘time-scale’.

Scientists now estimate that life first appeared on this planet four thousand million years ago. The story began with the coming into being of single organic molecules. These were produced, mysteriously, by the action of ultra-violet light on certain mineral elements. Then, after many many trials – and it’s difficult to avoid the notion of a will – the first single organic cells produced something capable of reproduction.

Thus it can be said that it took four thousand million years to produce the form and surface of the human body. Clergue’s camera recorded this image in less than one hundredth of a second. Do these incomprehensible figures touch the mystery of the sight of the figure in the sea? In a sense they do. What they cannot touch is the urgency of the image. What impresses or moves us always has an urgency about it.

In this case, the sense of urgency might be explained by the nature of human sexuality and by cultural conditioning. It can be put into its place within the history of our biological and social evolution. Yet such an explanation remains unsatisfactory because, once again, it ignores the fact that consciousness cannot be reduced to the laws of unilinear time. It is always, at any given moment, trying to come to terms with a whole.

From the idea of the whole come all the variants of the notion – ranging from astrology to the Koran – that everything that happens has already been conceived, has already been told.

There’s another Italian story, this time from the Piedmont.

One day a farmer was on his way to the town of Biella. The weather was foul and the going was difficult. The farmer had important business, and so he went on, despite the driving rain.

He met an old man and the old man said to him: Good day to you. Where are you going in such a hurry?

To Biella, answered the farmer, without slowing down.

You might at least say: ‘God willing’.

The farmer stopped, looked the old man in the eye and snapped: God willing, I’m on my way to Biella. If God isn’t willing, I’ve still got to go there all the same.

The old man happened to be God. In that case, said the old man, you’ll go to Biella in seven years. In the meantime, you’ll jump into that pond and stay there for seven years!

Abruptly the farmer changed into a frog and jumped into the pond. Seven years went by. The farmer came out of the pond, slapped his hat back on his head, and continued on his way to Biella. After a short distance he met the old man again.

Where are you going to in such a hurry? asked the old man.

To Biella, replied the farmer.

You might at least say: ‘God willing’.

If God wills it, fine, answered the farmer, if not, I know what is going to happen, and I’ll jump into the pond of my own free will!

What I find wise in this story is the space it offers for the co-existence of free will and a form of determinism. The ‘God willing’ offers a promise of a whole. The ‘God willing’ also, of course, poses insuperable problems. But to close this contradiction is more inhuman than to leave it open. Free will and determinism are only mutually exclusive when the timeless has been banished, and Blake’s ‘Eternity in love with the productions of time’ has been dismissed as nonsense.

It seems to me that throughout the course of a life the relation between space and time sometimes changes in a way that is revealing.

To be born is to be projected – or pulled – into time/space. Yet we experience duration before we experience extension. The infant lives minutes – without being able to measure them – before he lives metres. The infant counts the temporary absence of his mother by an unknowable time unit, not by an unknowable unit of distance. The cycles of time – hunger, feeding, waking, sleeping – become familiar before any means of transport. Most children face the experience of being lost in time before the experience of being lost in space. The first vertigo – and the rage it produces – is temporal. Likewise time brings arrivals and rewards to the infant before space does.

This is all the more striking if one compares a baby with a newborn animal. Many animals – especially those which graze – begin, within minutes of being born, a spatial quest which will continue all their lives. The comparative immaturity of the human baby, which obliges a long period of physical dependence, but which also permits a much longer and freer learning potential, encourages the primacy of time over space. Space is to animals what time is to sedentary man.

This human predisposition is linked with the early development of the human will. The will develops slowly – along with the ability to stand up, to walk, to talk, to name what one wants. But the will exists from birth onwards. (It is born from that expulsion.) In infancy the will selects very few objects from the full display of the existent. These few isolated objects, invested with desire or fear, then provoke anticipation and are thus delivered to the realm of time.

With age some people become more contemplative. Yet what is contemplation if it is not the acknowledgement, the celebration, of the spatial and the forgetting of the temporal? (For which the precondition is the abandonment of the personal will.)

Within the act of contemplation the spatial does not exclude time but it emphasizes simultaneity instead of sequence, presence instead of cause and effect, ubiquity instead of identity.

Curiously, when I write those words I do not think of a passive hermit, but of a dead friend who died because of his active politics.

His name was Orlando Letelier, a Chilean. He liked music. He was witty and debonair. And he had extraordinary courage.

He had been a minister in Allende’s government. When Allende was murdered and Pinochet seized power, Orlando and many others were arrested, held in prison, and tortured. Eventually Orlando was released on the condition that he left Chile. He travelled around the world, talking about the fate of his country. He encouraged other exiles. He persuaded certain governments to reduce or to stop their trade with Chile. He was eloquent and effective. Pinochet decided that Letelier had to be got rid of. His secret police arranged for a bomb to be planted in his car in Washington. One morning, when Orlando was driving to his office, with an American girl who was acting as his secretary, his car blew up. The girl was killed immediately, and Orlando, after he had lost both legs, died.

A day after I heard the news of his assassination, I heard the following:

Once I will visit you

he said

in your mountains

today

assassinated

blown to pieces

he has come to stay

he lived in many places

and he died everywhere

in this room

he has come between the pages

of open books

there’s not a single apple

on the trees

loaded with fruit this year

which he has not counted

apples the colour of gifts

he faces death no more

there’s not a precipice

over which his corpse

has not been hurled

the silence of his voice

tidy and sweet as the leaf of a beech

will be safe in the forest

I never heard him speak

in his mother tongue

except when he named the names

of patriots

the clouds race over the grass

faster than sheep

never lost

he consulted the compass of his heart

always accurate

took bearings from the needle of Chile

and the eye of Santiago

through which he has now passed.

Before the fortress of injustice

he brought many together

with the delicacy of reason

and spoke there

of what must be done

amongst the rocks

not by giants

but by women and men

they blew him to pieces

because he was too coherent

they made the bomb

because he was too fastidious

what his assassins whisper to themselves

his voice could never have said

afraid of his belief

in history

they chose the day

of his murder.

He has come

as the season turns

at the moment of the blood red rowanberry

he endured the time without seasons

which belongs to the torturers

he will be here too

in the spring

every spring

until the seasons returning

explode

in Santiago.

To the questions I ask of time, I have no answers. I only know that such questions are of the human essence and that any system of habits or of reasoning which dismisses them does violence to our nature. Since I first started writing I have been labelled a Marxist. A convenient category for others, sometimes a shelter for me. I believe in the class struggle and the historical dialectic; I am convinced by Marx’s understanding of the role and mechanisms of capitalism. Within the world historical arena, the fighting is mostly as he foresaw. The questions I ask now are addressed to what surrounds the arena.

I began with a story, I will end with story-telling.

Imagine a character in a story trying to conceive of his origin, trying to see beyond what he knows of his destiny, before the end of the story. His inquiries would lead him to hypotheses – infinity, chance, indeterminacy, free will, fate, curved space and time – not dissimilar to those at which we arrive when interrogating the universe.

The notion that life – as lived – is a story being told, has been a recurring one, expressed in multiple forms of religion, popular proverbs, poetry, myth and philosophical speculation. Nineteenth century pragmatism rejected this notion and proposed that the laws of nature were ineluctably mechanical. Recent scientific research tends to support the assumption that the universe and its working processes resemble those of a brain rather than a machine.

What separates the storyteller from his protagonists is not knowledge, either objective or subjective, but their experience of time in the story he is telling. (If he is telling his own story the same thing separates him as storyteller from himself as the subject.) This separation allows the storyteller to hold the whole together; but it also means that he is obliged to follow his protagonists, follow them powerlessly through and across the time which they are living and he is not. The time, and therefore the story, belongs to them. Its meaning belongs to the storyteller. Yet the only way he can reveal this meaning is by telling the story to others.

A story is seen by its listener or reader through a lens. This lens is the secret of narration. In every story the lens is ground anew, ground between the temporal and the timeless.

Featured photograph © David Strom; in-text artwork by Rembrandt van Rijn, A Woman in Bed, c. 1645-6