If you’re not careful the past will follow you around like a rumour. For you, a third-generation child of an immigrant’s son, it’ll sound like a tired reminder: oh, look how far we’ve come. Boats from Pondicherry, Colombo Port, Kolkata, Chittagong, carried refrains from elsewhere: stories of casting outward, some expelled or fleeing, landing on homes in Harrow, Hounslow, Newham, Southall, or Brent. You’ll shake your head, say to me: I’ve heard this one before.

In this city, yours is never the only story. Narratives of migration, settlement, assimilation, separation are shared across all communities. The urban mulch of South Asian, East Asian, Caribbean, African, Arab and Jewish families amass alongside one another; consequently, our myths come brimming. It’s like in that play where the rabbi delivers a eulogy for a Jewish grandmother and says she was not just a person but a whole kind of person. The ones who crossed seas heaped with entire villages on their backs, a journey the young find difficult to imagine. I agree with the rabbi. For you, grand voyages no longer exist. For my parents, your grandparents, having left so much of themselves behind, travelling to the Mother Country must have felt like oblivion.

It’ll be a while before you realise your grandparents are two of the most fascinating people you’ll ever likely meet. Your grandad rode nationalised rail when he first arrived. He stood amazed at the NHS back when it was properly funded, and the floors were still new. He used to smoke cigars, and his shoulders still shake when he laughs. Your grandmother, having arrived much later, can’t tell you about the Grunwick strikes, or the Bradford 12, or the Bhuttos. She can tell you about Ravi Shankar live in London, after the Concert for Bangladesh. She can tell you about raising two boys while working shifts at a supermarket in Willesden Green. She can tell you about making do with what little she had, and how so much of her life seems a miracle.

Do you remember when the Queen died, and everyone went on about the history she witnessed simply by living? My mum’s stories are like that except from the other side.

Of course, you’ll never ask her. Neither did I at your age. I was all limbs and acne at seventeen, all Church of England schooling, stripey ties and busy sexuality. The point of life was to bunn parental opinion. I also had a sense that another form of inheritance could be gotten elsewhere. In books, cinema, music – Woolf, Beckett, the Wu-Tang Clan, Bresson and Scorsese. Anything my parents offered seemed overcast with conservatism. Perhaps all that tradition and religion felt worth holding on to for them. For me, it only meant everything needed to be fought over, defied, and then dramatically renounced. I kept pushing away, and my parents feared I’d forget them. Why you have to be so different to other boys? It forced a distance that threatened to become irreparable.

I am astonished to find that I’ve weathered parenthood okay so far. You haven’t been easy. It’s just that you haven’t been as aggravating as I imagine I must have been. Much is due to the fact that we’ve spent our childhoods in the same city. I can recognise myself in how you navigate the place. How you code-switch the same way. Mad how it just come out with the mandem, alie? All those invented words inflected with heritages that are not your own. It sounds beautiful to me. It reminds me that a cacophony to some is harmony to others. Even the names of your friends are stuffed with syllables. We can both grieve the murals under Kilburn Bridge. When I mention Grenfell, you know what to say, and why it matters.

As we share our feelings of attachment, so too our estrangements. I notice the roll of the eyes whenever your aunties hand you a sequinned sari. Or when an Uber Eats driver, misplacing kinship in a recognised name, says: okay brother, god bless, take care, only to receive a stiff upward nod and a tight smile. I don’t fault your indifference. I only worry about your incuriosity. I wonder what catastrophe you think might occur if you drop the pose. Same way my parents must have wondered about me.

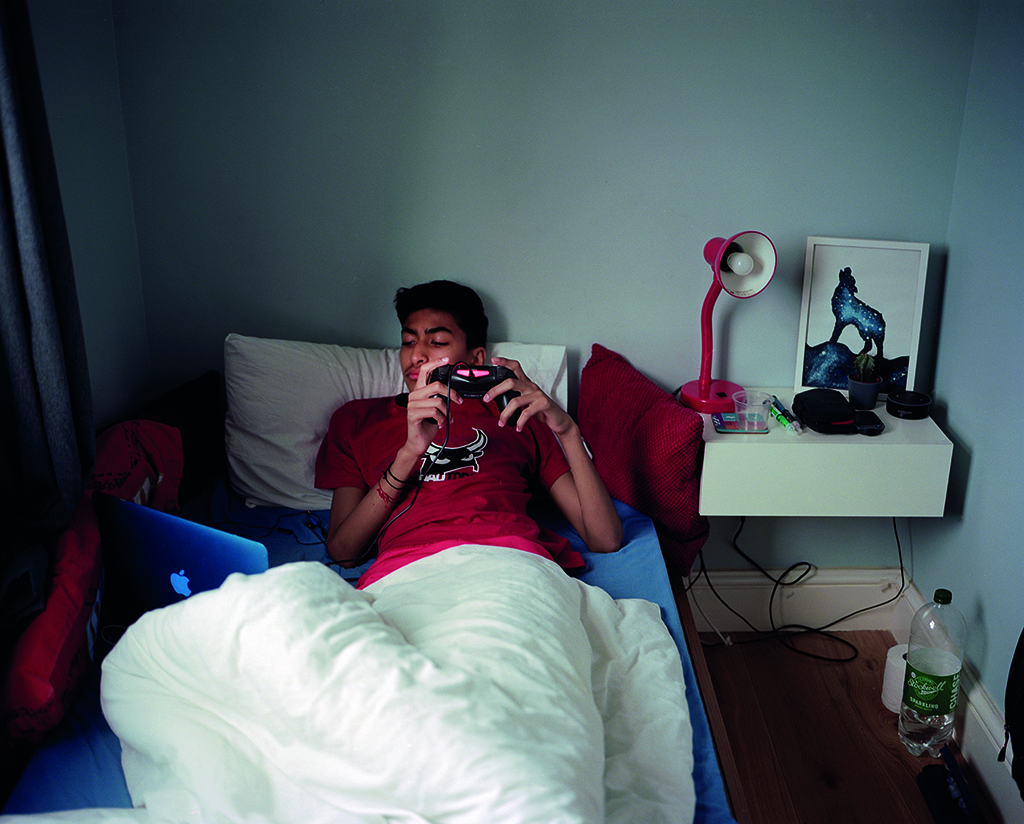

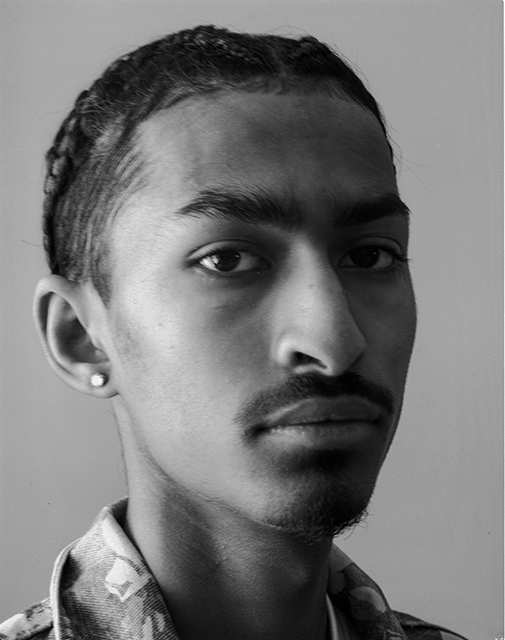

I sense it’s because you’re so used to cameras being pointed at you. Having grown up at a time when your image is misapprehended as authentic, and your artifice mistaken as true. You always know exactly what to do with your hands, and it terrifies me. You never let yourself shrug, slouch or tremble. You never allow yourself a moment’s spasm or blur. It bothers me because it was a blurring of identities that allowed for my own errantry. My generation was not as concerned with being seen or having our every posture interpreted. For you, an image makes sight sacrosanct. It wasn’t always like that. We were allowed to corrupt our own images. We risked a certain blindness in exchange for reckless recreation. I remember one summer when everybody played Apache Indian in excess. We styled ourselves as rude boys and magpies, as cultural gluttons. Brown boys wore canerows. The Black girls wore bindis. We blundered. But then again, ours was a far more forgiving generation.

There was a photographer who took my picture for the New York Times once. I must have come off a little shy because he asked me to think of somebody that made me feel mighty. It was a prompt to get me to loosen up. My eyes must have softened after I thought of you. I was remembering a moment when I’d held you at the hospital. You were wailing away, and I was trying to soothe you, but I was exhausted. I was holding you in my arms, and perhaps out of desperation, I whispered the words: duwa . . . duwa . . . shhhhh . . . That word duwa meaning daughter. I’d never uttered the word in my life before that moment. Duwa . . . darling go to sleep . . . It was as if my mother had lifted my chin having known what to say, and had offered it up in a whisper. It made me feel strong.

Now it’s duwa this, duwa that, duwa, come give me a hug . . .

When I was seven years old, my mother took me to temple in Croydon. I remember pointing at a carving of a worshipper on the wall, and I’d asked why the bodhisattvas sit like that. My mother told me it wasn’t as simple as saying a bodhisattva sits like the Buddha in order to imitate him. It is because each one, in sitting cross-legged, recreating the Buddha’s pose, his gestures and sayings, is bringing the Buddha back to life. That’s all a person is according to our Buddhism. A collection of gestures, mannerisms, good and bad habits, repeated expressions. A person is a set of patterns embodied for a moment. It’s all we remember after a person is gone. It’s all a photograph sees. And sometimes, without noticing, those old patterns get folded into us.

A good photograph can reveal so much about those patterns. It can see more than that thing you do with your hands. More than the lines that trace your nose that is your mother’s nose. It gets you laughing. Gets the way your shoulders shake when you laugh. I can see how easily you carry your contradictions. Your ambiguities. You never seem to doubt your self-worth. That assuredness, which might also be a pose, still lets you meet this city, this country.

Yours is a generation unashamed and appropriately electrified because you know instinctively what mine needed a lifetime to learn: to imagine yourselves into rooms that have never imagined you. That’s why you’ll embody the promise we expected for ourselves: to be a British citizen both exemplary and subversive, unrooted and unmoored, yet unburdened. How I envy your ambivalence toward belonging.

Those rooms change when you’re older. Of course, I hope you get the grades and graduate into the schools we dreamed of for you. But I hope by then you will have realised the value of your complicated patterning. The strength of walking into an austere Cambridge chamber holding the knowledge in your head of both T.S. Eliot and El Saadawi. Shakespeare as well as Wannous. Having already stitched together Iqbal, Gopal, Said and Roy, Rimbaud, Jay-Z as well as Kano. All of it falling out your mouth in atypical flood.

Remember, however, that yours is not the only story. And woe unto you, descendants of first voyagers, with your English first names and surnames of many syllables if you allow your histories to follow you around like mere rumour. There was an entire generation before you who chose to fly away and return, but we did return. We missed them. We wanted to know how to cook the dhal with buttered chillies. And now, at least we know the food. Can tell a good bhuna from the pretend in the City. But I wish I knew my mother’s words for don’t forget me, my duwa.

Don’t forget to ask us. Don’t forget to ask me what it was like to turn the century. Ask me what it was like to watch Desmond’s with my father, the way we watch Top Boy together today. Ask me what it was like to see Arsenal win the double. Ask me and your mother what it was like to march against the invasion of Iraq. Ask why it meant everything to stand next to you two decades later, in Parliament Square on Armistice Day, with a banner you made for yourself.

You’re a Londoner. Be a Londoner in every room.