And it wasn’t that day, or the day after, but sometime after that, you cried in your kitchen. You were alone in the house and had been for a week or so. Headphones sending sound into the silence, a tender croon stretched across drums designed to march you towards yourself. In an easy rhythm, the rapper confesses his pain, and so you stop and ask yourself, How are you feeling? Be honest, man. You’re sweeping debris across the kitchen tiles, reaching into the corners for far-flung flecks. Moving the brush in an easy rhythm, you begin to confess, your joy, your pain, your truth. You dial for your mother but she is still far away, wrestling with the grief of her mother’s passing. You want to tell her that you miss her mother, to confess that you lost your God in the days your grandma lost her body and gained her spirit, to tell her you couldn’t face your own pain until now. She would need you intact, you think. You end the call you initiated. You dial for your father, but you know he will not have the words. He will hide behind a guise, he will tell you to be a man. He will not tell you how much he hurts too, even though you can hear the shiver in the timbre of his voice. You decline the call. You dial for your brother, but he too carries the house of your father. He will not have the words.

So you’re in the kitchen, and you’re alone, but this isolation is new. Something has come undone. You are scared. You know what you want but you don’t know what to do. This pain isn’t new but it is unfamiliar, like finding a tear in a piece of fabric. You cry so hard you feel loose and limber and soft as a newborn. You want to pull and push and mould yourself back together. The headphones slip from your head as you slide to the floor, loose and limber and soft. You’re wailing like a newborn. You’re alone. You don’t feel in rhythm. There’s nothing playing. The music has stopped. A break: also known as a percussion break. A slight pause where the music falls loose from its tightly wound rhythm. You have been going and going and going and now you have decided to slow down, to a halt, and confess. You are scared. You have been fearful of this spillage. You have been worried of being torn. You have been worried that you would not repair, would not emerge intact. You lost your God so you cannot even pray, and anyway, prayer is just confessing one’s desire and it’s not that you don’t know what you want, it’s that you don’t know what to do about it. You’re on your knees, and the music has stopped and you’re wailing like a newborn. Your mother calls. You decline the call. She would need you intact and you are not so. You need to face this alone, you think. Something has come undone. Your cup has runneth over, and now it’s empty, the flow has ceased, but you’re still loose and limber and soft. You want to push and pull and mould yourself back together, so you rise from the cool kitchen tile. You stumble from kitchen to hallway, making it to your stairs. The wail has dwindled but you still feel tender. You gaze at the mirror on the wall, and though the music has stopped and the rhythm has fallen away, you confess your joy, your pain, your truth. You stop and ask yourself, how are you feeling?

The song which had been playing when the wobble became a spill was ‘Afraid of Us’ by Jonwayne, featuring a vocal sample from a group of Black women, one of whom was Whitney Houston’s mother, Cissy. In isolation, the hum of the melody raises the hairs on the arm, raises something within you. Have you ever been afraid of what lies within you, what you’re capable of? Anyway, when you mop up the spill and all that remains is a shiny kitchen tile and your delicate body, made soft by your tears, you stand in your living room, listening to ‘Junie’ by Solange. You raise your arms in casual jubilance, thankful to be alive. Such simplicity in gratitude. Simple progression too in this ode to funk singer Junie Morrison. Which is to say everything comes of something else. Which is to say from your solid ache comes a gentle joy. Which is to say, moving across your living room, affording yourself the freedom, to be, such simplicity in this, in the hazy, rhythmic bounce of the drums, intentional bassline, intentional and unthinking in your steps, approaching ecstasy, losing control of what you know, losing what you know. Born fresh, born new, born free. Bypassing something, the trauma, the shadow of yourself. This is pure expression. Ask yourself here, as you begin to move with quick, light steps, bare feet sliding across the floor, a delicate sweat forming: ask yourself here, how are you feeling?

The previous summer you asked the same question and found thin mist obscuring your form and detail. You found yourself in your room, unaware of the ache until you stood and felt a twinge in your side like a stray thorn had pierced you. You quietly got dressed and took a bus from Bellingham to Deptford, to a bar underneath the dim arches of the station, where musicians were said to gather and, channelling their voices through their various instruments, ask each other, how are you feeling?

You were annoyed at your own haze, at your lack of form and detail. But you made a choice, to be there, to want to shift, to want to move, and there was power in reaching towards yourself in this way. You thought about the intention of being, and how that could be a protest. How you were all here, protesting; gathered together, living easy. Spilling drinks on pavements. Two for £10. You’re all drinking now, but you weren’t allowed earlier, no, that table was reserved, all night, you just wanted a drink before the party next door, but no, your business was no good for them. You swallowed this and gathered together, easy living. Spill a drink on the pavement, the foam washing over blacktop like ocean spray.

The music drew you all inside. There’s a way to play the drums that makes hips move and feet jump. When one friend – first-timer – asked another – veteran – what it was like, she said, ‘The ancestors visit us and we let them take over.’ Maybe the ancestors are always within and you let them emerge. You saw it in the head rising above a curly mane of hair. You saw it in the hopping shoulders, the delicate curve of the spine. You saw it in the sweat pooling in the tiny waves of baby curls, at the bottom of a bunch of braids, nestled in the oiled frizz of natural hair; the rise and the fall of the Black body, no, the Black personhood, moving of its own accord, the beauty in her stamp, the nonchalant cheek on his playful features, the glint of a trumpet cradled by a dark hand in the light, an MC’s lips grazing the microphone; you were losing something, it’s not yourselves, no, but you were losing something, or perhaps it was like plunging into an ocean, the sticky tar of trauma washed away by the waves.

Dance, you said. Dance, sing, please, do what you must; look at your neighbour and understand they are in the same position. Turn to your neighbour and take one step forward as they take another step back, switch positions, move, move, move, become overwhelmed by the water, let it wash over you, let the trauma rise up like vomit, spill it, go on, let it spill on the ground, let go of that pain, let go of that fear, let go. You are safe here, you said. You are seen here. You can live here. We are all hurting, you said. We are all trying to live, to breathe, and find ourselves stopped by that which is out of our control. We find ourselves unseen. We find ourselves unheard. We find ourselves mislabelled. We who are loud and angry, we who are bold and brash. We who are Black. We find ourselves not saying it how it is. We find ourselves scared. We find ourselves suppressed, you said. But do not worry about what has come before, or what will come; move. Do not resist the call of a drum. Do not resist the thud of a kick, the tap of a snare, the rattle of a hi-hat. Do not hold your body stiff but flow like easy water. Be here, please, you said, as the young man took a cowbell, moving it in a way which makes you ask, which came first, he or the music? The ratata is perfect, offbeat, sneaking through brass and percussion. Can you hear the horns? Your time has come. Revel in glory for it is yours to do so. You worked twice as hard today, but that isn’t important, not here, not now. All that matters is that you are here, that you are present, can’t you hear? What does it sound like? Freedom?

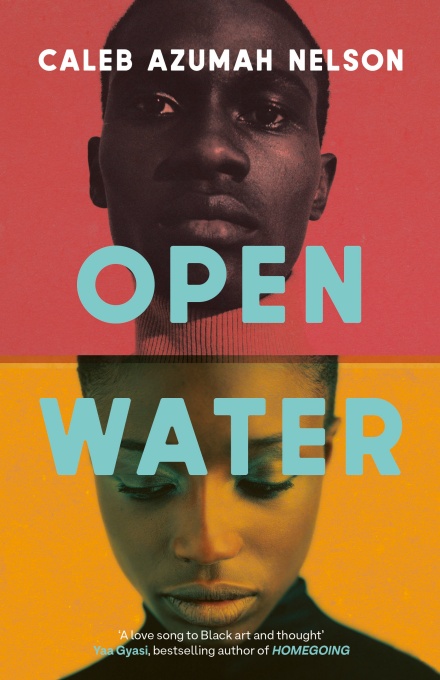

This is an excerpt from Caleb Azumah Nelson’s Open Water, out with Viking. Shortlisted for the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award 2021.

Image © Mark Chadwick