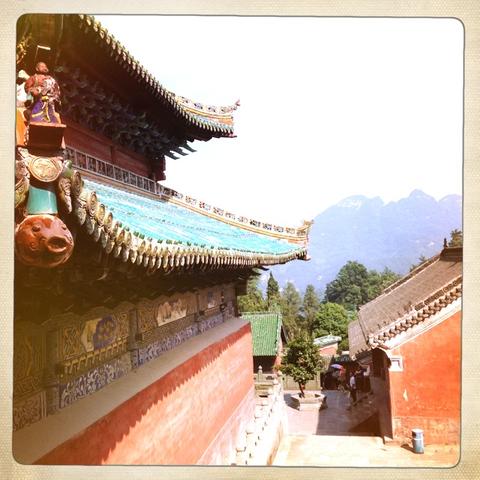

My first glimpse of Wudangshan is from my seat, wedged against my suitcase, on a bus winding up a road through rain and fog. With its red-walled, green-roofed ancient temples, it looks like the landscape of my childhood dreams, and it is here I’ve enrolled in a kung fu school for a month with one of my friends. Wudangshan is a UNESCO Heritage site, famous for its kung fu history, inspiration for the Wu Tang Clan, and the setting of many martial arts movies. The teachers at our school are in their twenties, and have long, thick hair that they wear sometimes in ponytails, and sometimes on top of their heads in topknots. They smile and joke all day long, except when they teach or do kung fu, and then they move with a stillness that seems to come from somewhere so deep it may be the mountain itself. Their grace is like nothing I have ever seen before in my life.

The danger with chasing fantasies is that the reality is often so different than the imagination. In the case of Wudang, there is the unexpected heat, and the swarms of mosquitos and small biting flies, and the teacher who has absolutely no pity for my weak and tired and jetlagged body. There is also the near-constant gastro-intestinal distress, and – oh my god – the toilets, which reduce me to near hysteria, but which, as I will later discover, are quite clean for rural China. There is the language barrier not entirely solved by the translation software the teachers run on their phones. But the harshest unforeseen reality is that of my own body, which I have not exercised for years, and which is not at all ready for the kind of training it must suddenly endure.

They drive the two serious, year-round students, boys aged nine and sixteen, much harder. They are merciless, swinging a bamboo rod above their heads and under their legs to make them kick higher, faster, and sometimes as punishment, swinging the rod against their thighs or hands. It makes a noise like a giant wind. One day they leave the nine-year-old in a corner, weeping in a squat position, with bricks on his head, his hands, his arms, and his knees. Another day they set padded blocks on the ground and stretch the boys into oversplits as they groan and cry. The teachers make them eat sour peepaws as punishment, but my friend and I are never punished: for us, they swing up into the trees and pick the ripe golden fruit to give to us as treats. Some days they make the boys do frog leaps across the courtyard, and other days they are made to do them up endless flights of high stone stairs. The boys suffer valiantly, and it looks terribly cruel and impossible until one of the teachers goes up himself: hop hop hop, so beautifully, so gracefully and effortlessly that I see why the boys persevere.

Meanwhile, I learn to stand still. I learn to walk slowly, while the teachers say, ‘No,’ and ‘No good,’ and ‘Cathy, you no good!’ with varying degrees of disgust or amusement. They begin to teach us the opening moves of the t’aichi forms. They adjust my posture, the tilt of my head, the way I hold my stomach, the way I hold my shoulders. Sometimes they double over laughing, just watching me stand. If I look up to watch them laugh, they correct the position of my eyes, which should gaze downward, at my nose. One day my teacher jumps onto the wall beside us as we do our stretches. One moment he is standing next to me, and the next he is on the wall, standing five feet above me. What’s incredible is that there’s almost no discernible movement: the jump itself so effortless it is almost invisible. Another day one of the teachers flies up a stone wall twenty feet high. He runs straight at it and then leaps, touches it once with one foot, touches it again with another, and there he is, looking down at us and laughing.

I know why the legends exist. I spend two evenings trying to push the master over with both my hands and all my strength, and he sways with each blow, but does not fall. He fills a plastic bag up with water and shows me that this is how you must be: relaxed and moving with the force, but keeping your balance and returning always to your center. Another evening I watch the year-long students do flips while in a corner of the courtyard the teachers dance with their swords, twirling, airborne. It is like ballet. We nickname one of them the magician king, because when he walks he moves his hands casually, beautifully, and the trees rustle around him, and it looks like he is summoning the wind.

I learn to love the morning runs. I begin to miss everything before it’s over. I sit in the kitchen every day to watch the teachers cook in the giant cast iron wok over a fire they build for each meal. I cherish the quiet at sunrise, and the sense of space as we run up that mountain road. I count the calls of the monkeys, and every day I eat the hot, steaming breakfast noodles, and wonder how many times they’ll make my favourite dish of eggs and tomatoes before I leave. One day my teacher tells me to close my eyes, because they are too distracted, looking at too many things. And I stand on the side of the road with my eyes closed, the cars driving by, and I see the shadows the teacher makes with his hands, and I stand still. Blind, I can feel him standing next to me, can sense where he is. I can feel the mountains, and the air. I can hear the birds calling, and the monkeys rustling in the trees. I can feel everything around me, alive, and then the teacher is fixing the tilt of my head and pushing my shoulders down, and then I am alone, he has left me, and I am standing in the right position, looking at nothing, totally still. And the teacher leaves me there for a long time, and I stand, quiet, at peace. I sense him come and go. Afterward, I cannot talk, I have gone so still, and we walk back to the school, quietly, single file. It is my one enduring moment of grace.

I do not want to leave the mountain. In the fantasy I came in search of, I stay. I grow strong. I learn to fight with a sword, I learn to leap like a frog, fly up walls and twirl sideways through the air. I learn to jump from mountaintop to mountaintop, to absorb punches like a bag of water. I learn to be relaxed in my body, I learn that stillness the teachers seem to hold so deep in their hearts. I learn Chinese. I learn to cook in their giant wok. I age in reverse and become a girl-warrior. I grow my hair long. I acquire that effortless grace that propels me into the air, twirling – sword in hand. When I swing my sword it swooshes in the air, and I feel all the time how they look: effortless, graceful and free.

But in real life, I leave. I say goodbye to the beautiful mountain, the teachers, the boys. I depart from Wudangshan just a few days shy of 4 weeks, scarred with mosquito bites and almost as clumsy as I arrived, but a little stronger, a little looser in the limbs. I came here chasing a fantasy, but what I’ll miss is the reality – the slow pleasure of daily life, of time spent in the companionship and tutelage of others sharing in the same pursuit, and of learning what the body can do. For the last month my body has stretched and jumped for me, pushed itself and carried me, and is beginning – at last – to relax. I can feel the difference in how I hold myself, in the quiet that has entered my mind. I want to keep going. I want to learn more. On the bus ride out, I want to stretch, to kick, to move slowly through the t’aichi forms. And for the next week, when I wake up in other cities, I wake early, and then I put on my shoes and run.

Featured photograph by liuzr99

In-text images by Cathy Chung