I can’t remember the precise moment Degas came into my life, but it was in my early years in London. For my brother and I, who had arrived in the UK as unaccompanied underage refugees and were struggling to acquire a new language, paintings spoke more than a thousand words. And that made us feel less lonely.

It was in those days that my brother bought a book on impressionism. I loved Degas instantly. The works that I got to know first were of dancers. And I danced all the time then, as if beyond merely existing, I was rooting myself through my dancing body in my new adopted country. Dancing made me feel free.

I felt so again when, years later, I visited Paris soon after my first novel The Consequences of Love was published in 2008.

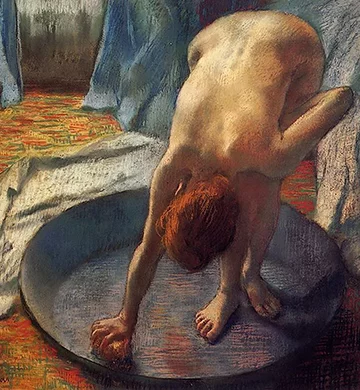

After a trip to a museum near the Seine, I bought another book on Degas. As I leafed through it sitting in a cafe, I saw his painting of a woman bathing in a bucket. I probably had encountered this image before, but what made it stand out to me this time was that I had the vague idea that my second novel would be set in a refugee camp, and I wanted art to be at the heart of the book. And here right before my eyes was an image that sparked my imagination: a naked woman taking a bath in a bucket.

The more I studied Degas’s woman bathing, the more I became enthralled by the power of nudity. When someone is nude, their history, background and surroundings all become secondary. Nude art represented the closest possible introspection of humanity, I thought.

It wasn’t that I was averse to exploring war, colonialism or other politically relevant themes in my work, but that I yearned for a more intimate study of the life of my lead character in the camp. I wanted an Eritrean–Ethiopian woman, and her mind, dreams, body, desires and inner world, to be the prime focus. I wanted Saba, which is what I called her, to live outside her country’s history. I wanted her to lead, not to be led by her country’s upheavals.

At that moment, I visualized Saba in that bucket instead of the French woman. The painting took me back to my childhood. This was how we bathed when we lived in the camp. As a child, I found being in that tiny, dark hut with my naked skin in a bucket full of water an exhilarating experience. And I could imagine my character enjoying it too.

I felt I needed a muse, to follow an Eritrean or Ethiopian woman as she went on about her day. Be there to see her wake up, observe how she showered. Study her as she did her hair and makeup, had her morning coffee, brushed her teeth. Follow her to work, spend the day with her as she negotiated the traffic of life and gain unfiltered access to her thoughts. I wanted to stay by her bedside at night, hoping to catch the details of how she slept. I truly believed that as a writer I could transcend myself, be a shadow in the life of this woman so that I could accurately capture her moods, loves, rages and hungers in their purest, uncensored details. I would paint her world on my pages as precisely as Degas did with his muse.

I mustered the courage and asked an Eritrean woman I knew in London. She told me she’d think about it. But then I had to leave for Brussels. As I surrounded myself with books more than people, something changed about my creative process. It dawned on me that I was, as Frida Khalo had said, the subject I knew best. I didn’t need anyone else, I thought. I could be my own muse.

I remember the day I stood in front of a mirror naked after a dance. I opened my body to my own inquisitive stare. I wasn’t looking at the massacre I had survived as a two-year old boy, the years I spent in a remote camp, and those that followed in Saudi Arabia. My image of myself now wasn’t disturbed by the challenges I had faced in London. I was looking at this half-Eritrean, half-Ethiopian man still standing, still dancing. Nudity enabled me to see me and not all that surrounded me. As I looked at the pictures I had taken of myself in different poses, unclothed by fabric or history, I began to discover things buried deep inside me: the woman in me as well as the man, the immigrant, the wanderer, the silent boy, the stubborn, flawed human being that I am. I was more than a refugee. I was one hundred other things too.

Taking these nude self-portraits inspired me to look beyond the obvious. So when the Ethiopian painter in my novel, who had studied art in Paris, complains that he can’t find a model to paint, his mind opens up when he finds himself standing in front of Hagos, my male character. The painter realises that a muse isn’t necessarily a woman. So he asks Hagos if he could pose naked for him. A male body can be a paragon of beauty too.

Today my novel is finally finished, ten years after I encountered Degas’s painting in Paris. Silence is My Mother Tongue is first of all a portrait of us, Eritreans–Ethiopians, of our intimate world, and the things we see when we dare to undress ourselves of our history. That even in the middle of ruins and tragedies, there are many beautiful things we hold inside us that we come to see once bathing naked in the glorious details of our own humanity.

Sulaiman Addonia’s Silence Is My Mother Tongue will be published by The Indigo Press on October 25, 2018.