In India the pursuit of romantic love can be a dangerous thing. Contemporary lore is crammed with the bodies of men and women who refused to be fitted into socially expedient ‘arranged’ marriages. Young women have been doused in petrol and set alight.Young men, bones broken, have been thrown into suitcases. Reporting from the northern state of Uttar Pradesh recently, I interviewed a fifteen-year- old sitting patiently on her haunches as a relative rubbed a home- made whitening paste on her skin to prepare her for her wedding. She was three years below the legal age for marriage, but she was to be married the following day. Her parents said it was safest. Lustful men might kidnap her, they whispered. Or, she might fall in love.

I didn’t meet a single person who had a ‘love marriage’ on my last trip to India, and whenever I have in the past, the fact is shared like a secret. It is loaded with melancholy, or fear, or defiance that begs to be unpacked. On an island in the Sundarbans archipelago, I once spent hours interviewing a vivacious schoolteacher named Toma Das. The only time a cloud fell over her face was when she spoke of her parents’ attitude towards her husband, a factory worker. They disrespected him, she said. They implied she chose poorly because she chose for herself.

Still, the experience of falling in love is an anxiously desired state. Bollywood encourages this impulse. Before love, say our films, there is nothing, and to fall in love is to be born.

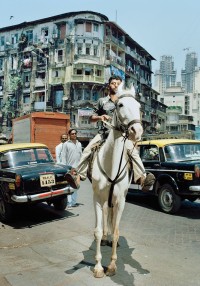

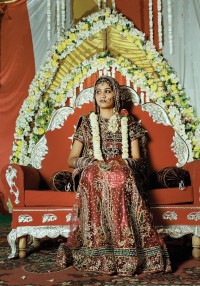

Max Pinckers deftly traps couples inside these two expressions of love: arranged love and film love. His brooding photographs show the hopelessness of some of these relationships, although they also display the rewards – expensive clothes, glinting jewellery, a white horse – because the ultimate reward of love for some isn’t reciprocity but a wedding, and the security it represents.

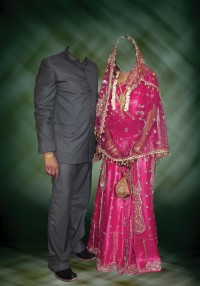

In Pinckers’s images the wedding clothes look stifling, as they often are in real life, and he has done well to pick up on this and to highlight the burden they may come to embody, with staging that resembles old-time Bollywood stills. Where some might see glamour in the artifice he has created, others will observe, perhaps from experience, drama and deceit.

The sense of suffocation goes beyond weddings, permeating the experience of Indians trying to express themselves romantically in a society where sexuality is feared. Love is little spoken of, and public expressions of love are taboo, so the idea of romantic love for young people is a constructed one. How one expresses love is not organic; rather, it is picked up in bits here and there – from films mostly, but also books, social media and porn – and pieced together to create a functional thing.

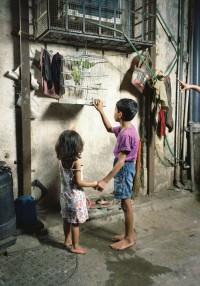

Since behaviour is also circumscribed by the smallness of shared living spaces, this piecing together, ironically, often takes place in public, and so Pinckers’s lens transports us to an isolated seafront and what appear to be abandoned mills, capturing secretive smiles and dreamy glances. He enters claustrophobic living spaces as well, to show how a relationship between two typically ends up accommodating the needs of as many as a dozen – fathers, mothers, sisters, brothers. In one set of four images, a couple whispers intimacies on a narrow bed set against a paper-thin wall behind which people bustle about their day.

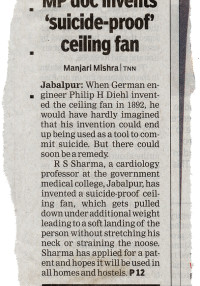

The hushed confidence, rather than laughter, or even an embrace, is a particular giveaway of a romantic relationship in India. The love here is furtive, quick and tense, and because of this it may appear comical to the outside gaze. But this is no comedy: the concealment of sexual love is a necessary skill, and it transcends class. To hide one’s love – from embarrassment or from the truth – is a matter of survival for some. Love can be a chokehold, acknowledge a few of Pinckers’s images – flames climb up a gauzy wedding dress in an allusion to dowry deaths; a noose fashioned out of a salwar kameez dupatta drops down from a ceiling fan. A newly-wed couple is shown with their faces rubbed out. But then the tightly entwined hands of another couple, clothes splashed with water, appear as though to say, No! Films are right. Love is a breathless, happy game.

As a reporter I’m naturally drawn to true stories, and in India love makes the news every day. It isn’t spoken of as love, though; it is camouflaged in euphemisms. In April, as I sat at a restaurant in a small town in northern India leafing through a newspaper, I read about a young couple who ran off to marry, only to be caught by the police. The woman, eighteen, was engaged to another man – theirs was an arranged marriage – and fifteen days after she was made to return home she could have been the woman in Pinckers’s photograph, dressed up in her finery amid a crowd of wedding guests. Her boyfriend was so desperate to break up the wedding that he wriggled into a skirt, stuck on a wig, slipped on some bangles and gatecrashed the wedding. The ‘body language of the youth’ gave away that he wasn’t a woman, reported the Times of India, which went on to say that the young man was quickly arrested and jailed. The newspaper led their front-page story with the headline boy dresses up as woman, but of course the real story was that two people in love were torn apart by tradition.

Pinckers shares this fascination for true stories, and the photographs he has plucked out of newspapers and the Internet illuminate most clearly how hard it can be to be young and full of wanting in modern India. A set of screen grabs reveals emails between a young woman on behalf of her friend and the Love Commandos, an organisation that claims to assist lovers under threat from family and social leaders. The woman’s tone dials up from urgent to frantic:

‘Its all bull shit!’ [sic] she writes, in what appears to be her last email to the Commandos. ‘She kept asking for help . . . But no one helped her. At last she finally killed herself today.’ The woman’s words collapse into an exhausted prayer. ‘May her soul rest in peace.’

All photographs © Max Pinckers / Neutral Grey