I have this one black-and-white photograph of my mother and father on their honeymoon in Angkor Wat and I stare at it all the time. I wonder: who were they? My parents. Two people that met, had a child, then fought to rise out of the wreckage. But at one point, a marriage existed. She wore a ring and he held her hand. In this photograph, they look like the Kennedys. There is the allure of education, sophistication, youth and beauty. My mother sits in an upholstered armchair, on the edge of the cushion, poised to get up. My father sits on the arm of the chair, leaning forward, clasping her hand, believing in things he will later regret.

In this picture my father is younger than I am now. I look at his face. Content and gentle, but mysterious too. Where did this mild-mannered confidence come from? Even though I have only known him as someone detached from his roots, his roots are in Utica, and they have defined him.

My father, like so many people who leave their hometown, was searching for more. The city that had answered his father’s needs was a flat and unexciting place for him and he knew the pattern of the life that he would lead there would be restricted; he needed to free himself and swing his arms.

He left for college at sixteen in 1945. American troops were liberating the first of many Nazi concentration camps, and pushing the Japanese out of the Pacific. Roosevelt had died, partisans strung up Mussolini and the end of the war was close. Carousel opened on Broadway, Bing Crosby won best actor at the Oscars for Going My Way and the Utica Blue Sox were dominating their minor league division. He graduated at nineteen, and boarded a Liberty Ship to spend a year in France. After that there was Harvard Law School and then two and a half years in the Marine Corps. He never really lived in Utica after age sixteen but it was his home until he began work in Washington DC with the US Treasury Department in 1956. He moved to Hong Kong in 1962 and has remained in the Far East ever since.

These were all choices that would have seemed strange to most Uticans. In those post-war decades there were jobs for life and disposable incomes that filled driveways with chrome-winged Buicks and homes with space-age kitsch. For his parents, America was the Promised Land. Leaving Utica was unnecessary. But for my father, it was an entirely natural path.

Most of his adult life has been spent living in Southeast Asia and now, sixty-five years later, considering this question from his home in Bali, he can’t trace precisely what it was that propelled him to leave. Where did that desire come from? He believed there would be a lack of momentum if he stayed.

‘But was that Utica or was that me?’ he asks.

There is a protective tone in his voice. Though he is glad he is no longer there, a deep affection and attachment lingers.

In the 1970s, my father, divorced from my mother, was living in Thailand. As the only child, I lived with my mother, a poet, in Manhattan. Twice a year he would return to visit his mother, my grandmother Mildred, in Utica, and I would join him.

For me Utica was somewhere we visited, with little reflection other than it offered glimpses of a simpler life. We would take the train heading north and five hours later, step into a world that was instantly less intense and chaotic; as if the lights had been dimmed and the volume turned down.

The train would arrive at Union Station, a sparkling Italianate building built in 1914. It was a cavernous space with high vaulted ceilings and thick marble columns. There was a barbershop, a restaurant, rows of benches and a shoeshine stand. It was an elegant entrance into a city that, unknown to me then, had begun a steady decline.

What I knew about Utica as a child was the hardship of winter – lots of talk about wind-chill, snow tyres and icy roads. It was a place with kind people, who paid attention to each other and listened. Ambition, though limited, seemed manageable and this was a welcome relief from the frenzied pace of New York City.

Pretentiousness was non-existent. Morals were unambiguous and pure. We would stay in the spare room with my grandmother, who lived at the Holland House, an apartment block on Utica’s main thoroughfare, Genesee Street. She had silk flowers and on every flat surface there was a crystal chalice filled with individually wrapped candy. Peppermints and butterscotch and pastel coloured mints. There was a bowl of wax grapes on the dining room table, an icebox packed with food, and a plastic slipcover on the sofa so that every time someone would sit down or stand up it would crackle. In the warm weather, the back of my thighs would stick to the sofa as pores opened up from the heat.

My father’s homecoming was always an event. ‘Harvey is here from Bangkok!’ Aunt Esther would shout to Aunt Frummie, who refused to wear a hearing aid. Everything would have to be repeated. ‘BANGKOK!’

Esther and Frummie were Grandma Mildred’s older sisters. There were four sisters and a brother. Aunt Oltie who I never met, lived further north, in Auburn. Aunt Frummie was hard of hearing. Aunt Esther never married and Uncle Moses had died in the ’50s. He had a divorced wife and son that nobody knew or talked about.

Mildred and her siblings were all born in Utica. Her father was from the Old Country, as they called it, and they were Litvaks (Lithuanian Jews), as were my grandfather’s parents. They immigrated in the 1890s to America. Having no idea what it would be like, they just knew it had to be better, a new beginning, a new life.

Jacob Winnick, my grandmother’s father, died when she was three months old in 1903, leaving a widow and five young children. He had been a great success in what would be known in Britain as a ‘rag and bone man’, but in America: a junk dealer. He bequeathed his mule to a man named Abie Nathan who took over the business.

My grandmother finished high school, worked as a salesgirl in a department store on Genesee Street, before she married. After that, she raised the children and perfected her brisket.

I never knew my father’s father, William Leve. He died before I was born. He was fifteen years old when he arrived at Ellis Island as Leib Piletovsky from Lithuania. He had no formal education and went to work in his teens, when his father died and there was his mother and younger children to support.

The Utica they came to found its first footings in 1817, when a man called Thomas Squire built a log cabin above the Clinton River where two Indian trails crossed. A railroad built to carry scrap iron to Detroit grew the town, but it wasn’t until the turn of the last century, when every year Ellis Island was disgorging a million of the huddled masses of ‘the tired and the poor’ that the small community founded by Squire, boomed with the influx of Italian, Irish, Jewish and Polish immigrants. William Leve was among them and Utica became a beacon of ethnic diversity, peaceful and prosperous co-existence across national and religious divides.

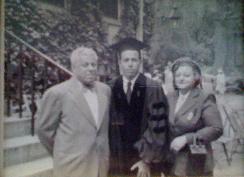

There is a photograph of my father at his law school graduation in 1952. His mother Mildred is on one side, his father, William, on the other. I can imagine the pride he must have felt – for an immigrant from the shtetl to have a son graduate from Harvard Law School.

My grandfather had two brothers – Uncle Myron was spoken about frequently because he married a Catholic. He lived in nearby Syracuse with his wife and son, and was an accomplished violinist, first violin in the Syracuse Symphony. My father remembers watching him play the fiddle. The other brother, Uncle Bob, lived in Oneonta further south.

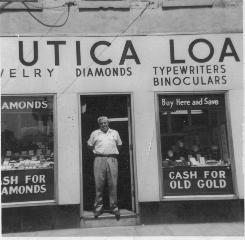

William Leve owned a small jewellery store called Judson’s & Harvey’s – named after his sons, but when the depression hit he closed it and established the Utica Loan Office. During the depression he could not afford to heat the room and on occasion he would stand by the windows and warm his hands on the light bulbs.

The Utica Loan Office (‘We Buy and Sell Everything’) was both a pawnshop and a jewellery store. He sold watches, diamonds and rings and he was a watchmaker. He would use a loupe with a magnifying glass in the closed end that would fit into the eye socket so that he had both hands free to open up watches and repair them. My father describes this tool with meticulous detail; a salient memory of his father at work.

Every watch in the store had to be wound up every single day and every fountain pen had to be replenished with ink. My grandfather, Bill, as he was known, was an excellent athlete; a handball star and he could beat the neighbourhood kids half his age. His other passion was checkers, and he was a champion at that too. There was often a checker game in the back of the store and when a customer came in, my father would run back and interrupt the game. Bill would play with Abe Marmelstein, a tall lanky man who always wore a hat. No one knew what Abe did for a living but he was always hanging around the store, chain smoking.

Later my father suspected that his father’s lung cancer, from which he died, might have been caused by Abe’s exhalations. Whenever I would hear that my grandfather died from lung cancer it would immediately be followed with, ‘and he never smoked a day in his life’.

During the Depression, a pawnshop was, for my young father, the place to learn about suffering and how unfair life could be. Everyone who came in had a story – ordinary folks down on their luck, temporarily they always said. The police used to hang out there too – on the lookout for those coming in with stolen goods. My grandfather was on good terms with all of them, right up to the Chief of Police, who later went to jail himself in the ‘Rockefeller Sin City-Mafia’ investigations in the 1950s.

The Leves lived in a house on Steuben Street when my father, Harvey, was born in 1928. They later moved to a house on St. Vincent’s Street, in a genteel area known as Corn Hill. My grandfather used to give my father and his older brother, Judson, twenty-five cents each on Saturday and they would go to The James Street Theatre to watch the cartoons, a serial, and a double feature – the talkies had arrived to populate their imaginations.

Later when I speak with their cousin Helen, she will tell me that my father never wanted to go, preferring instead to stay home and read, and I’ll be filled with pride upon hearing this, comforted by how different he always was.

The house on St. Vincent’s Street was a two-storey and they had the upper floor. The bottom half was occupied by the Dupre family, and my father recalls thinking the Dupres were very exotic because they came from French-Canadian stock. The children in the neighbourhood were mainly Jews, Poles and Italians. When my father was almost thirteen they moved to Oneida Street and this is memorable, he says, because it was close to his bar mitzvah and the move was a major distraction from his studies.

Whereas my father was the scholar, his older brother, Judson, was the practical one. He became a businessman who worked hard and flourished. Judson went to the University of Wisconsin for a year and decided he was not going to be a college student and started work with my grandfather before owning his own jewellery store. For a while he was also a partner in a restaurant. He dabbled in other things, and found his calling as an entrepreneur in developing shopping centres, which was an emerging market in the 1950s and 1960s. He developed them in other upstate New York towns in the region like Gloversville and Amsterdam, and built a business: American Shopping Centers, Inc.

Uncle Jud’s success was conspicuous. He wore beautiful suits, diamond cufflinks, travelled to Europe and tipped generously with hundred dollar bills. His objectives in life were never oblique. My father would take me to a Buddhist temple in Thailand but my uncle would take me to Saks Fifth Avenue. He bought me a camel hair coat once that I never wore but that he said made me look like a ‘polite young lady’.

My father valued the importance of balance and moderation; my uncle re-enforced the value of a dollar. My father deliberated, his brother acted. He would come to Manhattan, stay at the Regency Hotel on Park Avenue where the doorman greeted him by name, take me out for a filet mignon dinner and quiz me on my multiplication tables. It was only the best of the best. He loved thick ripe beefsteak tomatoes and women in short skirts. When I was seven years old he married Aunt Renee who looked like Raquel Welch.

She was, as everyone was, impressed with his bravado. Renee was Italian, from a large family, and in 1974 when they met she was twenty-seven. My uncle was thirty years older. After a four-month courtship they eloped and my grandmother Mildred adored her, passed on her recipes, and personally taught her how to make noodle pudding. Renee once asked my uncle, a reformed ladies man, why he chose her and he said because she was unspoiled. He would teasingly call her a ‘metziah’ which means a bargain in Yiddish. They were divorced, got back to together, remarried and had two sons, before divorcing again.

My time in Utica, like all time with my father, was episodic. There was a sense of escapism being there – no one was trying too hard to prove themselves to be worthy. And the city itself was brimming with character, snowed under and plagued, but resolute.

I would spend summers with my father in Southeast Asia where his life was unusual and tropical and he always seemed slightly out of context on our visits upstate in the gray tones of Utica. He would go outside in the frigid winter, walking briskly to the synagogue in a wool sweater and scarf, suntanned and looking like a movie star past snowdrifts five feet high.

This was an ongoing discussion among his aunts. Why wouldn’t Harvey wear an overcoat? It’s not just that he wouldn’t wear one, it’s that he refused to own one. To this day, my father does not own a coat and maybe it is his quiet unintentional rebellion against the blustery winters and conventional surroundings from his past. A sweater is temporary. An overcoat has permanence. Not needing one is a choice, a commitment to return only fleetingly.

At this point in my father’s life he is judicious and tender with his assessments of Utica. Perhaps it is the passage of years but he remembers it fondly as a decent place to work or bring up children and many of the people he grew up with have done just that and found the challenge and opportunity in Utica that was not in his nature to accept.

The residents of Utica have had full lives, just as he has, and though his adventures have been more expansive, his allegiance to Utica is uncompromised by his worldly experiences; it is where it all began and he respects and honours that. He once playfully said, ‘Happiness is Utica in the rearview mirror’, but no matter how far away he has driven, Utica has remained with him, in his stories and his essence. It has remained a part of his history. And therefore mine too.

Featured photograph by David Wilson

In-text photographs courtesy of the author