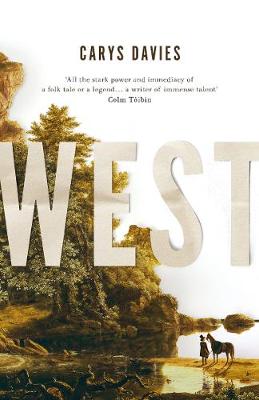

This is an excerpt from West by Carys Davies, published by Granta Books – a mesmerizing novella that depicts the uncharted wilderness beyond the Mississippi River. Order your copy here.

The whole thing had lit a spark in him.

For half a day he’d sat without moving.

He’d read it a dozen times.

When Bess came in from the yard wanting to chatter and play, he’d told her to run along, he was busy.

When darkness fell he lit the lamp and read it again. He fetched a knife and scored it around and folded it into quarters and placed it in the pocket of his shirt, next to his heart. He felt his breath come differently. He could no longer sit still. He paced about and every half hour he took the folded paper from his shirt pocket and smoothed it flat on top of the table and read it again: there were no illustrations, but in his mind they resembled a ruined church, or a shipwreck of stone – the monstrous bones, the prodigious tusks, uncovered where they lay, sunk in the salty Kentucky mud: teeth the size of pumpkins, shoulder blades a yard wide, jawbones that suggested a head as tall as a large man. A creature entirely unknown. An animal incognitum. People poking and peering at the giant remains and wondering what had happened to the vast beasts the bones had belonged to. If, perhaps, the same gigantic monsters still walked the earth in the unexplored territories of the west.

Just thinking about it had given him a kind of vertigo.

For months, he thought about nothing else. When Bess came asking if he wanted to play checkers or go for a walk outside to pet the new hinny with a white patch on its face, he said no. For several weeks he spent most of his days in bed. When he did drag himself to his feet he worked mechanically in the yard and pasture with the animals, and when the new mules and hinnies were born he went to town and sold them. When a winter storm took off half the roof, he repaired it. He cooked, and occasionally he cleaned, and made sure Bess had a pair of shoes on her feet, but he was silent the whole time and sometimes his eyes turned glassy and he would not let Bess come near him. The giant beasts drifted across his mind like the vast creature-shaped clouds he saw when he stood in the yard behind the house and tipped his head up to the sky. When he closed his eyes, they moved behind the lids in the darkness, slowly, silently, as if through water – they walked and they drifted, pictures continually blooming in his imagination and then vanishing into the blackness beyond it, where he could not grasp them, the only thing left in his head the thought of them being alive and perambulating out there in the unknown, out there in the west beyond the United States in some kind of wilderness of rivers and trees and plains and mountains and there to behold with your own two eyes if you could just get yourself out there and find them.

There were no words for the prickling feeling he had that the giant animals were important somehow, only the tingling that was almost like nausea and the knowledge that it was impossible for him, now, to stay where he was.

Before the summer was over he was standing in his sister’s house.

‘All I can say, Julie, is that they feel very real to me. All I can say is that the only thing in the world I want to do now, is to go out there, into the west, and find them.’

From Lewistown, Bellman proceeded through small towns and settlements along roads, which, though rough and broken for long stretches, brought him slowly further and further west. When he could, he bought himself a bed and dinner and sometimes a bath, but mostly he fished and hunted and picked fruit and slept out under his blanket. Arriving at the steep up-and-down of the Alleghenies, he did his best with his compass and his eye on the sun, and while he lost himself many times on the pathless slopes and along narrow tracks that led into the trees and then nowhere, here he was now, crossing from the east to the west side of the Mississippi on the ferry, which was a narrow canoe called a pirogue. His horse and his gear made the crossing on two pirogues lashed together with a wooden plank on top. The whole thing bumped twice against the landing and then it was still.

He was a little afraid.

The reason he’d decided to buy the black stovepipe hat at Carter’s in Lewistown instead of staying with his old brown felt one was that he thought he would cut a more imposing figure in front of the natives here, beyond the frontier; that they would think of him, if not as a king or some kind of god, then at least as someone powerful who was capable of doing them harm.

And as the months passed and he followed the Missouri River while it meandered north and west, and he encountered various bands of Indians, traded with them and had no trouble, he came to think that the hat had been a good choice and to consider it a kind of talisman against danger.

In St. Louis he’d stopped for half a day and bought two kettles, one for his own use and one to trade; more handkerchiefs and cloth and buckles and beads – all these to trade too, and with each new group, he exchanged his bits and pieces for things to eat. Then he drew a picture on the ground of how he imagined the great beasts might look, trying to convey the animals’ enormous size by pointing to the tops of available trees, pine or spruce or cottonwood or whatever happened to be nearby, but always the natives pulled a face that gave him to understand, no, they had seen nothing like the things he was looking for.

Bellman nodded. It was what he’d expected: that he had not yet come far enough; that he would need to go much deeper into the unorganized territories.

Slowly he traveled overland, not so far from the river as to get lost, but far enough that he had an opportunity to scour the occasional spinney of trees or forest or look out across the open ground or wander up and along some of the smaller streams and creeks.

Sometimes, in the thickest parts of the forest, he left the horse tethered and proceeded on foot for a day at a time, clambering over rocks and up and down gullies, splashing through mud and water, and returning exhausted in the evenings.

Every few weeks he looped back to the river in the hope of hitching a ride on one of the bateaux or mackinaws the traders used, making their slow and arduous journey upstream, and once or twice, he was lucky.

*

True to his word, Bellman wrote to Bess as he rode along, dipping his pen into the pool of ink in the metal container speared through the lapel of his coat. He also wrote to her standing aboard the low, flat rivercraft on which he occasionally managed to hitch a ride, or in the evenings in front of his fire before he wrapped himself in his big brown coat and his blanket and pulled his black hat over his eyes and went to sleep.

Over the course of the first twelve hundred miles of his journey he wrote some thirty letters to his daughter and gave them, in four small packages, into the hands of people he met who were heading in the opposite direction: a soldier; a Spanish friar; a Dutch land agent and his wife; the pilot of a mackinaw he passed as it made its way downstream.

The weeks passed and he shot plover and duck and squirrel and quail.

He fished and he picked fruit and he ate quite well.

He was full of hope and high spirits, and there were times while he was going along when he couldn’t help calling out over the water or up into the trees, ‘Well this is fine!’

Then winter came, and it was harder than he’d thought possible.

Long stretches of the river froze and Bellman waited, hoping to see one of the low, flat boats heading upstream, breaking apart the ice with poles, but there were none.

He met a small party of Indians, four men and a woman and a girl, who swapped some dried fish and a bag of corn mixed with sugar for one of his small metal files, but that was all. The large bands of natives he’d come upon earlier seemed to have vanished.

The days were very dark. He was cold and wet to the skin; the freezing rain ran down inside his soaking garments. His big squelchy coat was heavy as a body and there were times when he wondered if he’d be better off without it. Every few hours he wrung it out and water gushed onto the ground as it did from the pump at home, in surges.

Snow, then, cast itself over everything in deep drifts and an icy, unbroken crust formed on top of it. Bellman pressed on like a drunk, plunging and sometimes falling, the horse doing no better, both of them trembling and weak.

He had a little jerked pork and some of the Indians’ dried fish, the bag of corn that he eked out a pinch at a time. Occasionally he trapped a bony rabbit, but mostly even the animals seemed to have disappeared. Soon his dinner was only a paste of leaves or a stew of sour grass dug out of the snow. He gnawed on frozen plant buds and bark and small twigs, and his horse did the same. His gut tightened with shooting pains, his gums were soft and bleeding. He slept in caves and hollow trees and under piled-up branches. Every day he expected his horse to die.

Once, he was sure he saw a band of figures in the distance, fifty or sixty strong, on horseback, moving through the falling snow. They seemed to be traveling quickly, at a loose, rapid trot, as if they knew some secret way of passing across the landscape that he didn’t.

‘Wait!’ he called to them, but his voice came out like a rattle, a thin rasp that died on the cold wind, and the riders went on through the dusky whiteness until it covered them like a veil and they disappeared.

For a week he lay beneath his shelter and didn’t move. Everything was frozen, and when he couldn’t get his fire going he burned the last of the fish because it seemed better to be starving than to be cold.

And then one night he heard the ice booming and cracking in the river, and in the morning bright jewels of melting snow dripped from the feathery branches of the pines onto his cracked and blistered face, his blackened nose.

Later that day he caught a small fish.

Berries began to appear on the trees and bushes.

Winter ended and spring came and he continued west.

Photograph © Sasha Vasko