Too Hard to Keep

Jason Lazarus & Ariana Reines

Two nights ago I dreamed I was in a tight little skiff, tight as a knife. A skiff with two jibs on the open ocean.

Four days ago I bought a stack of books about UFOs, Egyptian hieroglyphics, the east African slave trade & Keats, from a junk store on Manhattan Avenue. The man at the till had a dyed black mullet and did not appear to find me or my purchases charming. He was when I came upon him debating the merits of the different Van Halen eras with a coworker. An authentic-looking Iron Cross dangled from the dog chain around his neck.

While waiting in line to pay I tried working up the courage to haggle by visualizing my face sheathed in an aura of vaguely erotic, bleak belligerence. I felt myself glaring the glare of a French actress in of one of those monotonous, atmospheric Nineties movies in which boredom, concupiscence & loathing either leads to mirthless sex or murder. But my heart was weak. The Iron Cross on the man with the mullet made me feel unlucky.

By the time we met across his counter I was too demoralized for banter.

For those who have forgotten, because I sort of had until it loomed in my eye, the Iron Cross was an old Prussian military medal restored to use by Hitler.

I’m having a post-Twentieth Century problem here, I thought. Not so much a problem of the space between word and thing, but the Doppler way that things, that images, once detached from their worlds, must grope their way back through the mind, back out into the world of sense, the world of what can be spoken – back out into this world. The new world. By which I mean my world. By which I mean yours.

Next thought: I’m being too generous, and simultaneously: Why was I too scared even to ask the man, perhaps in a tone of conspiratorial jocularity, about his choice of jewelry. Well for one thing I thought, in another state he might shoot me. That KKK man in Kansas who’d just tried to shoot Jews in a parking lot but only succeeded in murdering a couple of regular people. Might the times be changing, I thought. Now that the archives of the world were open, it might finally be time to step up my game in what I had long thought of as the heretofore pathetic mode of genocidal consciousness.

Of all the trinkets to dangle over the disjecta of outcasts, the meek, the broke and the departed.

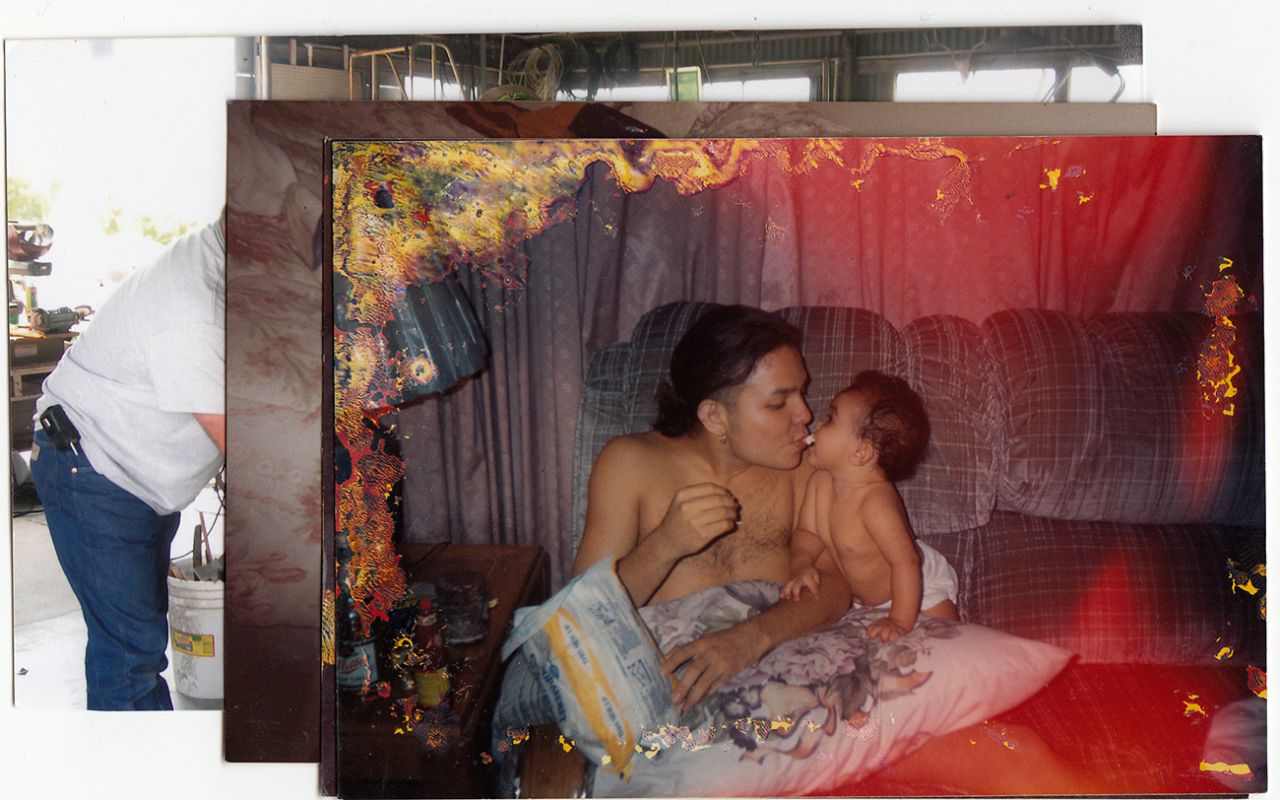

In high school I had a recurring nightmare. All the photographs in the world were swirling in a kind of chemical whirlpool. It was like they were being washed. They no longer belonged to anyone. They were full of faces I didn’t know. As is often the way with nightmares it was and still remains difficult to describe the terror this dream put in me. Now that it’s been years it’s come to me that my old dream might have had something to do with a museological approach to the commemoration of mass death, which I’d first glimpsed in a coffee table book I used to pore over in my grandmother’s house, a book about the Holocaust Museum in Washington DC. In that book I saw cathedralic shafts, somber and stately and lined with a seeming infinity of photographs showing other people’s dead wives and husbands, fathers and mothers, brothers and uncles and children and friends. They were not my family but they had died like mine. So somehow they must all belong to me, these dead with their searching eyes. My grandmother tended to handle her memories the way whatever was done in public taught her to. She was a lady. And always very submissive about the smallness of what she felt she knew. She could take no for an answer. She kept her shame at having survived at all largely to herself. When they heard her accent, when they learned where she had come from and what she had survived, Americans paid her a strange respect, almost as though she possessed something like fame. It seemed Americans respected anyone who’d been part of something big.

My Nineties: public monuments to memory, not memory itself.

By the time flickr became a thing I knew the dread with which my old dream used to fill me had now become a public fact, the kind of public fact so stupefying, so omnipresent & so occasionally entrancing it can hardly be spoken of.

Sooner or later you have to make a choice, I thought, feeling whipped as I walked away from the junk shop. Make the choice to act as though other people are consciously choosing.

Then I thought: that I should have at last become so weak as to feel brutalized by a junk seller’s Nazi jewelry while purchasing from him used books of the kind the losers of the world find comfort in – the colonized, the genocided & those deprived of myth & culture, among whom I clearly count myself – is one ringing irony in the total truth of capitalism: to discover profit pawning even secondhand dreams & banalities surely has something very ugly in it.

But what exactly, I thought, I’m not sure I’ll ever be able to say.

Four years ago the same store bought the contents of a storage unit I had accidentally on purpose no longer been able to pay for. I lost everything, which wasn’t much. I lost a few dozen notebooks and a few hundred love letters, some old clothes & sticks & antlers. I lost a dried dead bat in a jewelry box and a suitcase full of old sweaters full of the fragrance of my grandmother and her Oil of Olay.

There are days I can’t even remember the things I want to know. There are times I can’t see the faces of the ones I love. Sometimes I look at a picture on the computer and it seems to have gone a little grainy, as though one or two of its pixels have rotted. There are days my mind is a bowl of shit through which I can only barely glimpse the names of the ones I’ve lost, even I’ve only lost them for a few days, a few hours, names which in my drying mind increasingly become terms, and even the very thought of them hardens in me like a stone, a stone that has absolutely nothing to say except ‘the very thought of you’.

If it were among the duties of a new priesthood to do the remembering for us, even do the mere keeping for those of us who can no longer bear such work, then we’d be talking about a misery, a kind of science fiction priesthood, one forged in times very much like these.

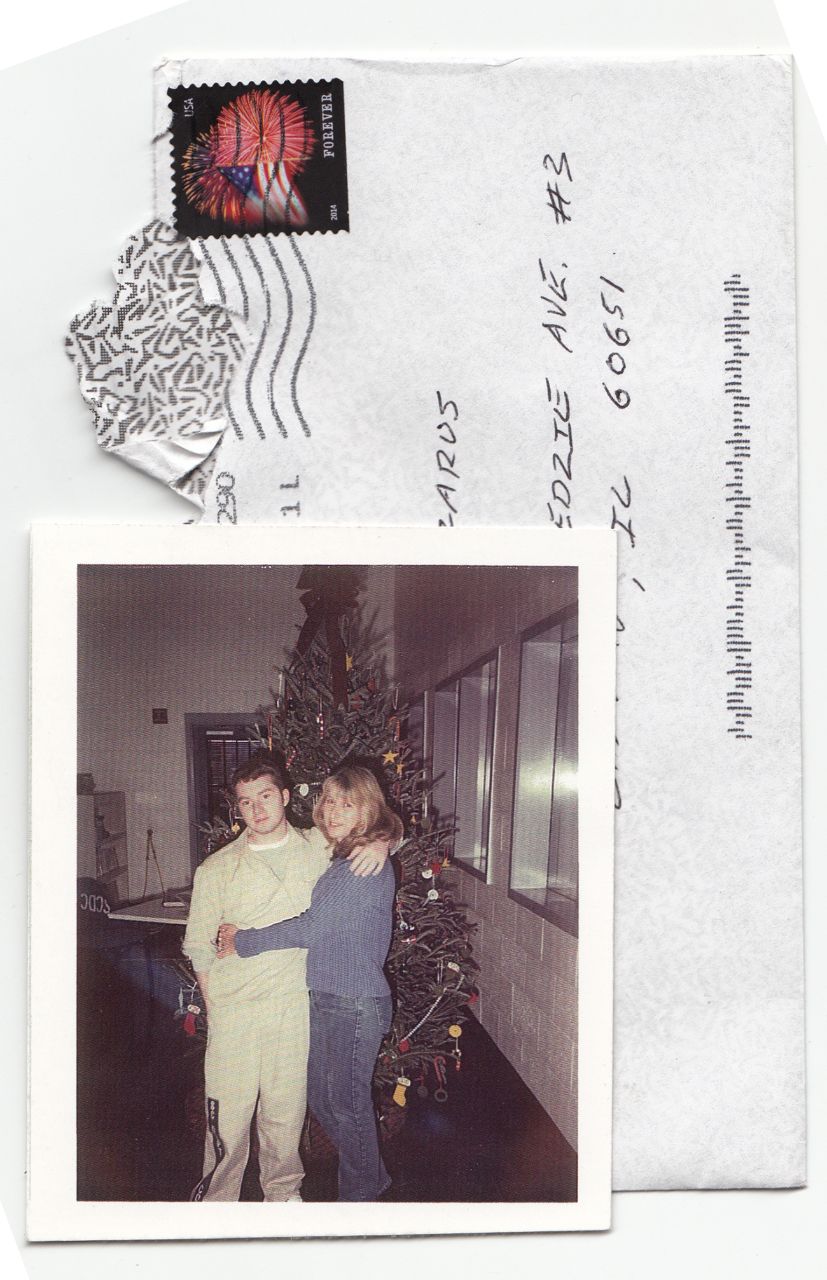

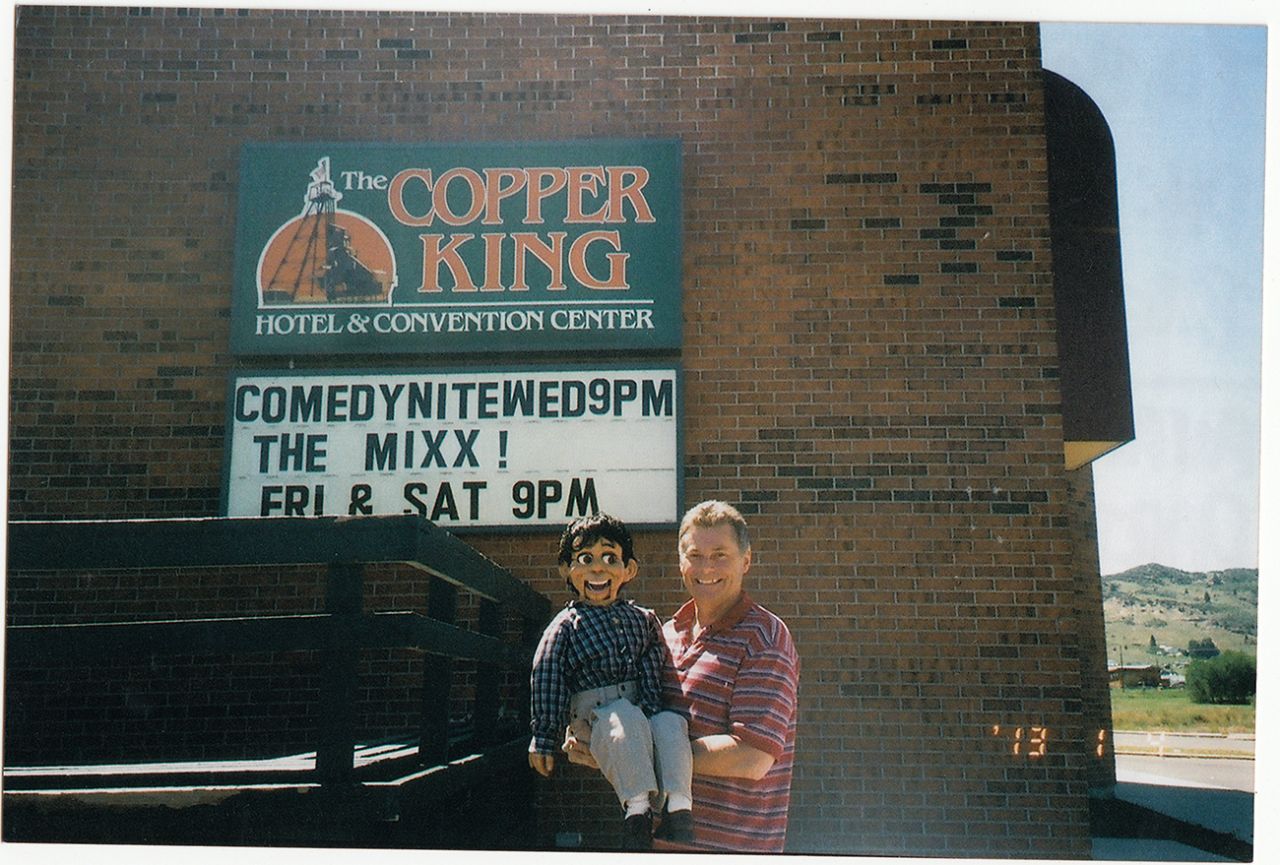

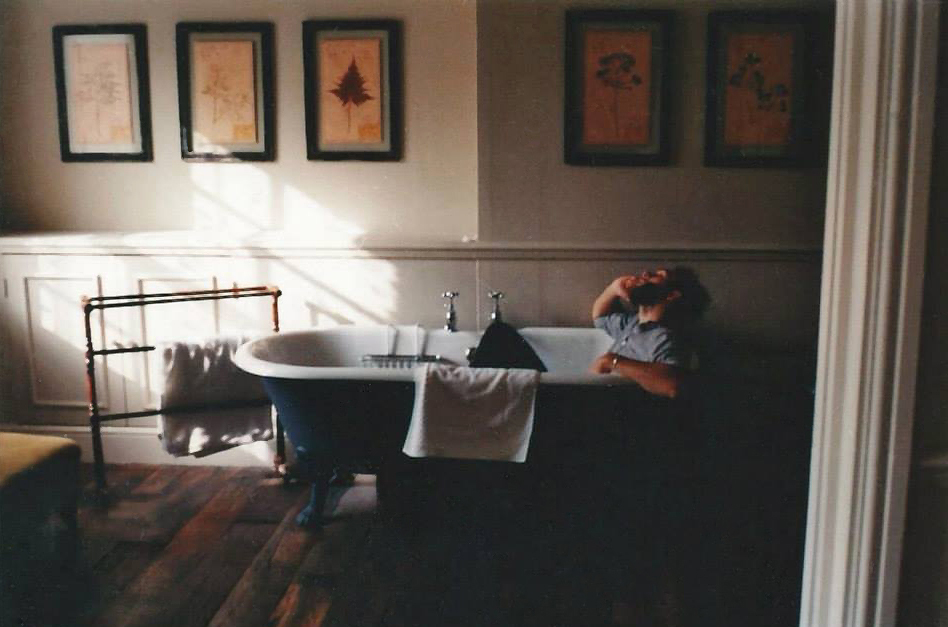

T.H.T.K. (2010 – Present) is a live archive of photographs deemed by public participants as ‘too hard to keep’. See more selections from Lazarus’s project here.