Christmas time. Madrid. No snow. Every five years or so snow falls over the statues on the rooftops of these buildings and over the statues of the Retiro, our city park, including one from the 1800s of the devil as a fallen angel. This statue is reported, inaccurately, to be the only public statue of the devil. Spaniards say it is the only one anyway. But this year our fallen angel has no white covering.

Lights strung up through Chueca, the gay district close to my cathedral. In Puerta de Sol, the main square of Madrid, where people often protest one thing or another, there is an enormous golden tree of lights. Not that many Christmas trees. Madrileños are not accustomed to the Christmas tree. In general, the tree in the home is a custom that has been imported from other countries, and so the trees often look forlorn or out of place here – at least to my eye, as if they are not quite speaking the language of the holiday. Los Reyes, on 6 January, is a much grander holiday here, celebrating the three kings, with parades and floats and sparkling candies thrown about to children everywhere.

Word reached me here not too long ago that the poet Mark Strand had died. This was his adopted city, too. I had only just gotten to know him; we’d met twice for coffee in New York where I’d been stalled with my visa paperwork, he’d been kind and fatherly towards me, a father and son dynamic I continue to find comfort in, well into my fifties. We got on. When a poet finds another poet they can laugh with it feels like some door has been unlocked and one is hopeful to walk through that portal when time allows for comradery – for poetry is perhaps the most solitary of the arts.

Mark told me about his experiences with Elizabeth Bishop in Brazil, how although she lived far away from the buzz of the American literary scene she remained keenly aware of the players and the prizewinners. This passing on of unique biographical vignettes of past poets is part of the glue that makes up poetry friendships, especially from one generation to the next. It is how we understand poetic genealogy, for we make up our own class in a sense, our own tribe, a tribe based on the art. In that regard it is utterly egalitarian. Who your parents were or what your skin colour happens to be or how much money you have doesn’t really count for much. It is all about the art.

I knew Mark was sick but still I imagined a lengthening friendship. He didn’t look ill at all. So I left the Upper West Side, waved goodbye, started my life in Spain and a month or so later he was dead. His death shocked me. I never seem to adjust to the finality of death: death comes and I am still not braced for it. Emails stop. Funny stories stop. ‘The joking voice’, that phrase from Bishop’s poem about loss, is utterly absent.

Mark loved the city where I am writing, where I now live and work. He knew my street for it was near here that he would buy supplies for his watercolours. He met his late love here. And he had been living here until recently. The city suited him. As it apparently does me too. It has appropriated me the way Berlin appropriated Christopher Isherwood: suddenly the far-flung place becomes us. Writers often seem to belong where they did not start: Mark in Madrid, Isherwood Berlin, Bishop Brazil, Merrill Greece. Isherwood once wrote: ‘It is strange how people seem to belong to places – especially to places where they were not born.’ As if writers need another language to understand their own better. Or is it that we need some kind of hiding place in order to see more clearly?

We pray Tuesday through Friday here at the Cathedral. I work for a little unknown branch of the Spanish Anglican church, that description itself is a conundrum – Spaniards supporting a faith with an Anglo-Saxon racial designation in its very name. My work life is entirely in Spanish. The British church across the city will have their Lessons and Carols service tonight, where all the British expats will gather and sing. It is a curious place I occupy in my work, a foreigner within a foreign church.

I had written Mark and asked his permission to place his name on the list for those wanting healing. Mark was not a religious person but he was intrigued by my choice to become one. And when he died I prayed for him then, too. His death recalled other deaths, and in particular the death of another poet I had known, James Merrill. Merrill had been an early encourager of my work long before I had ever published a poem. I have wanted for some time (twenty years to be exact) to recall that relationship, remember it as accurately as I can, which of course will be inaccurate the more the years pile on top of the past. So after I uttered Mark’s name in our Cathedral . . . Por los enfermos . . . Por los muertos . . . and after my office duties were complete, I went back up the four flights of stairs to my rooms and found my old essay on Merrill, here in Madrid. I dusted it off. Every five years or so, I seem to have returned to it. Seeking to recall the past, seeking to praise something. Perhaps I am trying to find some way of continuing my conversation with Mark or James.

Hadn’t Mark been curious about my priestly life when we were having cupcakes on the Upper West Side? Hadn’t he wanted to know more about my past? I was self-effacing as usual, delaying my response to listen to his story. I remember he was ebullient because his new pain medication had given him a boost of energy. We’d both been on the long list for the National Book Award and were cut, so we were sharing in our loss. Actually, I think we laughed about our loss; the commiseration was healing. What was more important was this: two poets talking. Thank God we did lose, otherwise we might not have had those cupcakes. I feel myself turning to Mark now and answering him a little more about my past, my choices.

1990

Harvard’s Divinity Hall

Sometime in the spring of 1990, I wrote Merrill a fan letter. The fan letter was actually a veiled cry for help, now that I look back. About to graduate from Harvard Divinity School, I was growing painfully aware that I was not going to go into the religion business. Not yet, anyway. When the young experience reversal all seems lost; there’s not as much patience of what the future might hold when young. My decision to attend seminary, all my actions over the prior two or three years, felt misfired: I’d taken all the courses and somewhere along the way I had faltered. I was not in any ordination process. I had taken all the steps to muddle through college, then graduate school, and found myself not opening a door at the end of it but rather standing at the tip of a gangplank.

It was true I’d come to seminary with the idea that if I had admired the poetry of George Herbert so much I might try to be like him, only three hundred years later. But I got to the end of the coursework and I did not feel capable of being a priest: it felt too daunting, I felt immature, not up to the task. In my case, two years of coursework was not enough. I did not even know whether I should stay in my Episcopal tradition or go Catholic. Turns out, I would need twenty more years of life experience. My youthful self felt like a failure. Now, with hindsight, I can see that I would eventually arrive right on time, at the age of forty five. But in that moment I suppose it was somewhat like getting an MFA degree in poetry and realizing, degree in hand, you had nothing, actually, to say. After placing the order for my cap and gown, a nun, a very direct woman, almost militaristic, a fan of Mary Daly, asked: ‘Maybe a religious career is not for you?’ It was not a question. What was I doing? Where was I going? Behind this neurotic hand-wringing, there was something larger brewing. The Aids crisis, that distant drum in college, was now a fire alarm in my ears. The sound made it difficult for me to think.

I chose to walk away from a life in organized religion for the time, and turned, instead, to poetry. It was something I could pursue without some kind of public declaration. And the truth was I probably knew more about the biographies of poets at that point than I did about any of the characters in the Bible. Impractical as it sounded, I began thinking of writing a book of poems then and there, in Divinity Avenue, in that three storey brick dormitory where Ralph Waldo Emerson had once lived. It could be my little church of ideas. Herbert’s one book had been called The Temple. In the days after it was published in the seventeenth century, people sometimes called it ‘The Church’. I began to think of my book that way, as some kind of spiritual dwelling where I could make sense of things. If I wasn’t going to work in a church I’d make one instead.

And so, from the electric typewriter on that desk and with boxes around me, I wrote James Merrill. I was seeking counsel, some kind of conviviality, some voice in the wilderness, something to counter the nun’s voice. Curious to note, I suppose, it was the work of a lapsed Episcopalian I was seeking. I got his address from the daughter of Frederick Buechner, whom I’d known for years. Frederick Buechner and Merrill had gone to prep school together at Lawrenceville. I thought, surely this man who received direction from the upturned teacup of a Ouija board might guide me, guide me somewhere, if not into the church then into something spirit-filled. And, perhaps most unconsciously of all, although I would never have been able to voice it or put it into words until now, I was trying to figure out how I was going to make sense of being a gay man. How we spoke of being gay and how we speak of it now has changed radically in my time on the planet. In 1990, it was still a cagey business. At least for me.

To my surprise, Merrill wrote back. Quickly, as I recall. What would follow for five years was one of my last relationships forged through letters.

1991

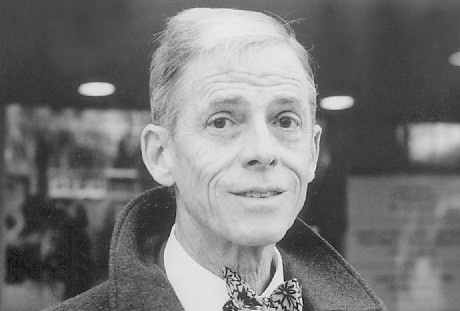

About one year into this correspondence, I met Merrill. He gave a reading in Minneapolis, where I was living at the time. Together we rode the elevator up to the rooftop cafe in the Walker Art Center. Minneapolis, with its conglomeration of skyscrapers, glittered out of the corner of my eye like a jar of fireflies. Merrill was intriguing to the general public, partially, because he was the heir to the Merrill Lynch fortune. He had been rich since he was five, ‘whether I liked it or not’, he later wrote. He was the product of the financier’s second marriage. In that glittering night, it seems to me now he was glittering too. Fate had sent me someone to offer decorating advice for my home of verse. Someone to show me how to build rooms, how to appoint them, someone who had already built mansions.

Merrill had once said to Edmund White about a poetry enthusiast, ‘Why does he want to meet us in the flesh? Doesn’t he realize the best part of us is on the page and all he’ll be meeting is an empty hive?’ I did not find that to be true. I found the poems came to life even more by meeting Merrill. So much so that when I read them now, two decades later, I still hear his voice – that cultured upper East side New York accent, coloured by four years at Amherst, years living abroad and a mother from Jacksonville, Florida: his tone was a combination of tony barbed zingers delivered with arched eyebrows and softened by a Southern chivalry.

That night he read from his poem ‘The Broken Home’. I had read this poem several times and was pleased he’d told me beforehand he would read it in public: I felt like an insider. On the table were candles to match the glittering Minneapolis night. It was a full house. The poem contained these lines:

Tonight they have stepped out onto the gravel.

The party is over. It’s the fall

Of 1931. They love each other still.

She: Charlie, I can’t stand the pace.

He: Come on, honey – why, you’ll bury us all.

The soft half-rhymes of ‘gravel’, ‘fall’, ‘still’ and ‘all’, evoked the melancholy that was in the Minneapolis fall air that night, and in the fall air of the poem. Half-rhymes rather than true rhymes denote things being yoked together with some force. Or at least some sense of unlikely elements being set together for the first time, mirroring the parents’ relationship. Then we hear those Waspy voices familiar to anyone who has been to those old yacht clubs on Cape Cod: there is the comfy chiding of parents, and the child witnessing the grand mysterious drama of parents, the romance that is as big as a movie screen for each child, yet as we know from the previous stanza, this ‘marriage [is] on the rocks’. The film does not have a happy ending. Merrill never was one to resist a double entendre, embodied here in the slang of ‘marriage on the rocks’ with the literal image of the mother and father stepping on the gravel.

In person, Merrill made every attempt to blend in, it seemed to me. He wore a second-hand green blazer and Birkenstocks. He wasn’t showy: on the whole he wanted to camouflage his American aristocracy. This made him more approachable to people, I imagine. Maybe his deference in manner and dress was partially a result of a life devoted to poetry: what shrives one of excess like poetry, the most money-repellant and fame-discouraging writing life of all? And wasn’t it astonishing, some must have thought, that a man with so much capital on his hands devoted his life to poetry when he clearly could have done many other things? But then, as I would come to feel in my life, if indeed the muse of poetry laid claim on you, there was not much room for anything else. You were charged.

He had the subtle guardedness, he once said, of someone who ‘never had to make a living’. Because his living had already been made by his father, he courted a certain paranoia of one who needed to be on the watch for those who might hope to make their living off of him. At least that was my sense of him, as I recall him now, as I try to remember how I read him. That’s what I would say to Mark, if I had managed to linger longer after our cupcakes.

Memory is the most unreliable of narrators, but a need to recall his kindness towards me pushes me forward. Let that go down in the poetry record: his kindness. I liken his attentive hospitality towards me, if you’ll allow me a priestly fancy now, to Christ’s message, spreading love through attentive listening. The Benedictine monks stress this sort of hospitality in their monasteries: every guest is treated as if they were Christ. There was something Benedictine about Merrill’s embrace of the stranger who wanted to know more about poetry. Later I would learn that there was a veritable crowd of novices such as myself that Merrill regularly welcomed without complaint.

No one particular person or thing wholly contributed to my life in poetry, but I have no doubt meeting Merrill and his encouragement played a part. Rich, eccentric, acerbic, flirty, childlike, Cary Grant-suave, talented, winner of all the poetry prizes one could think of, indifferent to religion – he was my poetry evangelist. I was very young then, and although I had grown up in some privilege my parents would eventually go bankrupt and live out a nightmare of houses being sold at auction and embarrassing foreclosures. But what Merrill could and did give me had nothing to do with money.

I admired his talent and his achievement. I was grateful for his warm welcome. And behind the gratitude probably a tumble of other emotions. Envy. I did not yet have my own life. It would come. But when you are trying to figure out what that is, the temptation can sometimes be to want someone else’s life without having the vaguest idea of all the difficulties that life would entail. Since poetry produced little or no money, having a life that had sufficient money in it sounded agreeable. The envy left me as time passed. My twelve years at Brooks Brothers, after being unable to land any engaging work in prep schools or newspapers, would actually be a great tutelage for me in the ways of the world. But I see that now that I am fifty and Merrill is dead. I did not see that then. Merrill’s grand background appealed to me. I wouldn’t mind, I thought, moving in his circles. I didn’t know that no matter where you stand in this world with money there are problems. Then, in that cafe, I knew little, other than that I had an undying desire to be close to poetry.

There was a seventeenth century Italian courtier named Baldassare Castiglione, who wrote: ‘practice in all things a certain nonchalance which conceals all artistry and makes whatever one says or does seem uncontrived and effortless.’ Merrill had developed this nonchalance to a fine art and that gave him a Christopher Isherwood-like boyishness in his mid-sixties. Nowhere was this nonchalance more in evidence then when the conversations turned to poetry. Perhaps he had picked up this habit from his first meeting with Elizabeth Bishop? When they first met in New York, he had hoped to talk about her poems. He wrote of the experience, in his memoir, A Different Person: ‘I naively thought I could spend most of the lunch telling her how wonderful I thought [a particular poem] was. It only took a couple of minutes, and whatever we talked about from then on, we were on our own. Elizabeth wasn’t affected at all. I think she knew how much she had put into her poems. She must have known they were wonderful. Maybe out of a kind of superstition she didn’t want to make too much of them in talking about them.’ Merrill wanted to subtly instruct me in this art of conversation. He was one of the earliest champions of Bishop, and he wanted to pass on to me what he knew of her, not to show off that he knew her, but to help me. It was an altruistic gesture and I have never forgotten it.

The day after that reading, I drove him to the farm where I was living at the time (owned by my family, about to be sold). The humble Minnesota landscape delighted Merrill. The Midwest hooted and shifted with unseen creatures: foreboding, ominous, capable of sudden, blinding darkness, the elms big as opera stage sets. We lunched and sat out on a small screened-in porch attached to the front of the one hundred year old house and ate stromboli and drank Orangina. He spoke of the New York City Ballet, his old friend, Frederick Buechner, and the virtues of contact lenses. Dutifully and ceremoniously he signed all the books by him I owned. Before we left, Merrill wanted to walk some of the property. We had not crested the first knoll when he said he was out of breath. ‘Can we go back?’ he asked. I dropped him back in the city, and when I returned to the farmhouse I realized he had left his rainbow-coloured wool scarf behind, a gift from the poet Mona Van Duyn. When I called him to tell him he said, ‘This is good luck; it means we will see each other again.’

Aids, the plague decimating gay men, was much in the news by the time I met Merrill. This was causing Americans to speak of their sexualities in ways they had not done before. Merrill wrote that the closet dissolved around him. Yet I remember him talking that first time we met, in the car, leaving the farm, on I-35W back to Minneapolis, about how he was still deciding whether or not to let his poems be in a ‘gay anthology.’ The Midwest blurred by us: a suburb, a farm, a cow, an elm, another cow, another farm. In the same breath, he was thinking about the memoir he was to write and pondering the frankness that prose brings. He worried his mother might disapprove. These were daring gestures then.

Today it is a challenge for younger gay people to understand the kind of atmosphere that was whirling around us. The worst TV evangelists proclaimed God was punishing gays for their sins. I had five classmates in college who were gay and I do not think we ever said the word between us: one blew his head off, and the other four died from the virus. Everything was whispered and superstitions abounded: people were not sure if you could catch the virus from a toilet seat or from the Communion chalice.

Poetry made all the more sense to me as something to turn to for spiritual solace. I knew my gay classmates were more complicated than proofs from obscure Biblical passages in Romans or Levitcus that damned homosexuals. It would take me until my forties to learn these texts were taken out of context and the Bible was far more porous than I thought. One of my classmates that died had wanted to be a poet and a priest and by thirty he was dead, just after graduating from Harvard Divinity School. When I called to ask how he had died, the mother would not give me a straight answer. Only when I persisted and called the college did the dean whisper into the phone: ‘Aids.’

Perhaps, reading this, you may begin to understand, why Merrill chose to tell hardly anyone he had tested positive for HIV. He was probably already quite ill when I met him. He was guarding the secret even as he was extending his generosity to me. I remained completely ignorant of his illness until long after his death.

1992

I began to show him my feeble, awkward attempts at poems. He cordially welcomed them, although I have often wondered if he did not care for them so much. If that was the case, it seems now to me all the more endearing that he kept encouraging me.

Merrill was a formalist, what was being called a ‘neo-formalist’ in those days, resurrecting sestinas, villanelles, pantoums and hundreds of other metrical patterns. This approach all sounded natural in his voice and came to him as fluidly as tying his shoes. Many were following in his wake. I, too, would learn from form, and from him about form: but in my own case, I would end up breaking most of the moulds I poured my thoughts into. From his example, I went and purchased several books on how to write forms, little do-it-yourself kits, and like Czerny scales I regularly worked on those forms for years.

In between bites of cupcake Mark told me he’d done much the same thing. He was irritated by some of his Columbia students because they hadn’t taught themselves all the forms. We both agreed this was just part of what one did. Crazy poets.

As if to encourage my industry, Merrill sent me a Smithsonian engagement calendar that year, inscribed with the rhymed couplet:

What does the new year hold for Spencer Reece?

Poems at dawn and nights of stellar peace.

1993

Merrill’s home in Key West

In the winter of 1993, after an exchange of several letters and postcards, I saw Merrill once more. It would be our last encounter. He was wintering on Elizabeth Street in Key West, near a black spiritualist church. I had flown down to spend the spring holiday with my parents in a home that would also soon be sold. With a penchant for acquisition and then depletion, we lived in a house of cards.

The house where James stayed was owned by his companion of thirty years, David Jackson. The house was a Bahamian ‘shot-gun house’ with a long corridor from the front to the back and various rooms off the sides. The term ‘shot-gun house’ came from the idea that you could shoot a gun straight through it. Palm fronds brushed against the screens, painting their green blurs. Neighbours were flush with one another. Propellers zoomed overhead, interrupting conversations. In the background, the sound of neighbours loving or fighting or both, and behind that sound the spirituals that would sometimes vibrate in through the floorboards, making them like tuning forks beneath our feet. He had just finished reading Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited and I remember we talked about how it was almost more of a poem than a novel.

Merrill wrote a poem called ‘Clearing The Title’ about that house. The poem, shot through with the ambivalence connected to his relationship with David Jackson, begins:

Because the wind has changed, because I guess

My poem (what to call it though?) is finished,

Because the golden genie chafes within

His smudged-glass bottle, and, God help us, you

Have chosen, sight unseen, this tropic rendezvous

Where tourist, outcast and in-groupie gather

Island by island, linked together,

Causeways bridging the vast shallowness

This poem describes a gay marriage before that term could be said casually. The title itself puns: is this a real estate title he is after or is there an allusion to the title-change that occurs with a marriage licence? Is that not the title that needs to be ‘cleared’ up? I have often wondered. Merrill’s epic poem, The Changing Light at Sandover, channels spirits through his Ouija board, and the marriage of Jackson and Merrill is writ large as they are the two men following the upturned cup on the board. Thom Gunn says the poem is ‘the most convincing description I know of a gay marriage.’ This poem is its prelude.

Much of gay life then was anything but clear. I think I must have, unconsciously, been looking to Merrill as some kind of pioneer, a man who had cleared some of the way ahead, and that I must have been wondering where my own place might be on that landscape. And there I was in the house built by a gay marriage. Would I ever have such a thing?

Merrill often liked to remind me that the word stanza in Italian meant ‘room’. A poem then, was like a house. He himself had built a small housing development of his life, using all his forms, with such grace, that much of his life went into his rooms. ‘Clearing The Title’ is a big house of thoughts and sentiment: nineteen stanzas of eight lines each; the first line rhymes with the eighth which gives the read the impression of the material being bookended. If this poem had an interior decorator the style would be a chic clutter. Merrill is barely able to include all the things he would like to put into these rooms; they are packed with artifacts, no wall space is left available, much like the actual decor of his home. The rhyming words in this poem – ‘behaving’, ‘waving’, ‘matter’, ‘patter’ – verge on the comical. Later in the poem the rhyming words will be ‘dead’, ‘past’ and ‘oblivion’: tragic words registering another emotional spectrum.

Emily Dickinson once described her thoughts as running around like squirrels, which could apply to this poem too: Merrill, here, discusses interior decoration, alchemy, stray cats, the hippie festival dedicated to the setting sun in Key West, the practice of burying the dead above ground due to the coral rock and the Greek mathematical invention of the Archimedian screw that twists and raises water. But surrounding all the objects and discussion, are the two men. Two gay men who have become more roommates than lovers. Langdon Hammer, Merrill’s biographer, wrote: ‘Sexually he was more than a little promiscuous – from say the late 1960s to the late 1970s.’

In his Essays, Montaigne writes: ‘The ceaseless labour of your life is to build the house of death.’ At the time I met Merrill he must have been thinking along such lines. I hear this solemn note now in the poem as he goes from his chummy humorous welcome, then lightly refers to something more troubling, as if the poem were anticipating his diagnosis and death.

Merrill and Jackson, I saw, lived on opposite sides of their house. Merrill had a new boyfriend, Peter Hooten. Yet here, in the poem, Jackson is solidly placed in the poetic concrete. It is as if the poem itself, with its accretion of stanzas and details, is shoring up something to last, something to stand. Chain-smoking Jackson, as I found him there, had all yellow fingertips, watched cartoons all day and was rumored to have a penchant for calling in rough trade prostitutes. I was also told Jackson had been an accomplished concert pianist. In the poem Merrill writes of ‘the all-night talk shows of the dead’, perhaps referring to the sounds coming across the hall. The rhymes towards the poem’s end recall Jackson’s shocking Miss Havisham-like appearance: ‘skeleton’, ‘scene’, ‘dead’, ‘past’, ‘oblivion’. In contrast, there is the vim of Merrill’s pleasure in the making of verbal architecture.

Allan Gurganus, introducing Merrill at the 92nd Street Y in 1993, said, ‘he admits without confessing’. ‘Clearing The Title’ emphasizes landscape and interior, but barely, just detectable, perhaps only felt by someone who had actually been in that house, is a pentimento of surrendering, passion lost, sorrow without conclusion: the poem is sadder than it first seemed to me. Hard not to hear Bishop’s rallying cry, here, that many situations tend to be ‘awful but cheerful.’

‘Clearing The Title’ ends:

(Think of the dead here, sleeping above ground –

– Simpler than to hack a tomb from coral –

In whitewashed hope chests under the palm fronds.

Or think of waking, whether to the quarrel

Of white cat and black crow, those unchanged friends,

Or to dazzle from below:

Earth visible through floor cracks, miles – or inches – down,

And spun by a gold key chain round and round . . .)

Whereupon on high, where all is bright

Day still, blue turning to key lime, to steel

A clear flame-dusted crimson bars,

Sky puts on the face of the young clown

As the balloons, mere hueless dots now, stars

Or periods – although tonight we trust no real

Conclusions will be reached – float higher yet,

Juggled slowly by the changing light.

Vatic-voiced, the last words of the poem ever so lightly reference his greater, longer work. The speaker observes the clarity of the setting sun and it reminds him of a young clown juggling. The sky wears a mask: a curious metaphor, a clown juggling the whole universe. Merrill’s poem is personal until the personal burns off: life’s tragedies are greeted by a red-nosed clown; the camera focused on the small drama in the little Bahamian house pans out. What it reveals, by the poem’s end, is a long-term gay union, ambivalent in its triumphs. Life, the poem seems to say, is absurd. This is the message shot through the hallway of the poem.

That last visit, when I was in Key West, he had been busy with a seminar wholly devoted to Elizabeth Bishop, the first of its kind. Bishop’s star was starting to rise in the literary firmament, eclipsing Anne Sexton, her friend Robert Lowell and many others. Bishop was making her entrance and Merrill was bringing that word to the congregation of writers that would gather there.

Mary Jo Salter spoke the first afternoon of the conference about how Bishop had been her teacher at Harvard. She had always called her ‘Miss Salter’. A wistful chuckle went through the audience, acknowledging how this proper address was fading from the culture. Bishop had written on Salter’s last assignment, ‘I hope Miss Salter will continue to write.’ That brief human contact and encouragement again, like some kind of bidding.

Later, Merrill gave a speech at the dedication of a plaque on Bishop’s home at 624 White Street: ‘it is Elizabeth Bishop’s human, domestic presence we need to feel this morning. We who loved and revered her, miss her keenly still. And now even the stranger passing through Key West may feel pride to find a great poet’s residence so lightly yet so decisively commemorated.’ After the commemoration, I went back to Merrill’s house with him, where we had tea and biscuits and he made me practice iambic pentameter by reciting Bishop’s poem ‘One Art,’ emphasizing that the accent fell on ‘to be lost.’ He was fond of the poem and had just recited it at a funeral. Out the window the daylight broke across the water like confetti. Florence Nightingale believed light was second only to fresh air for healing and there was something healing in that light.

Night fell and the island shimmered like a tin ornament. In the auditorium that night, Merrill was surrounded by a large crowd. His bemused head was tilted back. His eyes were filled with joy at the celebration of Bishop: ‘Of all the splendid and curious work belonging to my time, these are the poems (the earliest appeared when I was a year old) that I love best and tire of least. And there will be no others.’ Joyful, then. The joy was stirring in the barn. It was contagious, like one of those revival tents that could be heard from Emily Dickinson’s bedroom window. I looked forward to writing Merrill more about this sense of joy, joy, a word Merrill wrote was ‘rusty with disuse / deserved and pure’. From the darkened balcony that evening I looked on.

Gurganus, eulogizing Merrill, wrote: ‘There was, in James’ work, a Dante-esque sense of a parallel universe; there was a breeze always blowing through Jimmy from somewhere else.’ His HIV positive diagnosis, in 1986, following ‘Clearing the Title’, began to stirr up those breezes. By the time I met him, six years into his illness, he was guarding his secret with the deftness of an expert host. The breezes were clocking gale force winds.

1994

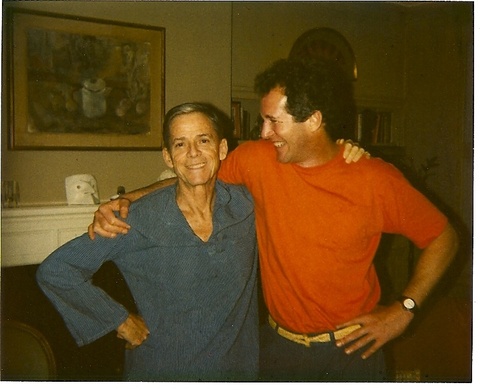

Merrill with Peter Hooten

Before Merrill died, at the age of 68, J.D. McClatchy wrote in his diary of the response to a frantic call from the poet: ‘When I arrived, near midnight, the apartment was in ruin. Furniture upended, pictures thrown from the wall, J’s bedroom door smashed in, glass and broken lamps all over the place. [Peter Hooten] was red in the face, frothing at the mouth, ranting about how ungrateful and slave-masterish J is, how he’ll commit suicide, etc.’ Hooten had developed a drug and alcohol problem. McClatchy was Merrill’s literary executor and the only person he confided in about his diagnosis. At the kitchen table at the farm, Merrill offhandedly said, regarding Hooten, ‘There have been a few scenes.’ Now, reflecting back on that time in Key West, it makes sense why after he showed me his collection of OEDs he’d inherited from Auden, he boxed them up to send to McClatchy. He was signing things away, tidying up so as not to leave things unattended. Years later I met Hooten by accident in Del Ray Beach. At the mention of Merrill his face turned wistful. Was it regret? He had said he missed Merrill’s wit. I said, ‘Yes, I miss it too.’

Late 1994, before he died, Merrill wrote a masterpiece, to my mind and ear, entitled ‘Christmas Tree’. He once said he had had a bad experience with nature and felt guilty he’d written so little about it. So, perhaps, it is no coincidence this last poem he wrote is about nature, albeit nature contained, screwed into a stand, decorated and indoors. A concrete poem in the shape of a tree and in the voice of a tree – given these strictures, the odds of a failed poem might be great. But in Merrill’s hands the poem flourishes. Herbert’s poem, ‘The Altar’, in the shape of an altar is one of the only other poems in this vein I consider successful. Perhaps now more than ever order and structure kept personal chaos at bay.

The spirit of the tree coalesces with the spirit of James – ‘the stripping, the cold street, my chemicals / Plowed back into the Earth for lives to come’ – all this could be James. A Christmas tree and a family tree all ending on the page. Of course, behind all the commercialization, the Christmas tree is referencing Christ, and that spirit might loom here too for a reader if they wanted: a triptych of three solitary non-fertile speakers.

In the 1995 Poetry magazine version, the poem is centered and there is a whimsical asterisk on the top. In his Collected Poems, the poem is left-justified minus the asterisk. Printed in this way, it shows you half the tree, as if you were peering at if from another room, rather than head-on. The other half of the story, then, becomes something unprintable, something withheld. Either way the poem holds its own.

Subtle, stoic, Merrill was not going to talk to people about his hidden diagnosis, because it did not ‘bear / Now or ever, dwelling upon’. The tree displays Merrill in a way he never showed when I knew him, thinly and artfully disguised as Bishop in her poem, ‘Crusoe in England.’ Merrill often said how sad he found that Bishop poem, a dramatic monologue about Crusoe, musing on a life spent exploring but now at its end. Merrill’s poem carries a similar sadness, hidden behind the artifice of another voice. Merrill belongs nowhere in this poem: the tree’s identity is disappearing as we ‘read’ it from top to bottom. We enter with greens and lights and a star on top. We end with the stump. Despite Merrill’s abhorrence of the overly emotional or sentimental, the last lines on the base of this tree get to the heart of the matter: ‘today’ breaking into ‘dusk’, ‘time’ ending a line, ‘love-lit’ breaking into ‘gifts’, ‘so’ breaking into ‘receptive’. The words are simple, one or two syllables, the grammar truncated, consisting of ten incomplete sentence fragments, mimicking shallow breathing – the sound has a staccato, Morse code kind of urgency. The ‘to be’ verb which greeted us at the top of the tree punctuates the poem’s end through its absence: ‘the end beginning. Today’s / Dusk room aglow / For the last time / With candlelight. / Faces love-lit, / Gifts underfoot.’ Four missing ‘to be’ verbs; the basic verb of existence becomes a ghost.

Merrill’s eminent death breathed life into a hackneyed talisman that decorates a religious holiday. Merrill always expressed hope in his ornament. Here, however, the surface jars with the reality sharply. ‘The point from the start was to keep my spirits up,’ the tree says. Merrill always did that, I can attest to that. He was, to my mind, heroic. By the time he sent me the last postcard I received from him from Tucson, there must have been ‘a primitive IV / To keep the show going . . .’ – ‘Holding up wonderfully!’ says the mother in the poem, which of course, resonates with his own mother, who would remain unaware of Merrill’s diagnosis. She would live six more years after Merrill died. As ‘The Broken Home’ eerily predicted: she buried her son. Off and on, Merrill had alluded to the guilt he felt in not having produced grandchildren for his mother, and here in the Christmas tree, that sense of a tree cut down emphasizes that.

Five months before Merrill died, he wrote me a letter. I was just leaving the beloved farm where he’d met me and would be moving on to my job at Brooks Brothers:

Your good long letter – ‘awful but cheerful’ – is here and I grab the opportunity to send you a shorter one in return. Speaking of awful but cheerful, you must know that is what Elizabeth Bishop wanted on her gravestone. Now a young friend of mine made a pilgrimage to the Worcester, Massachusetts cemetery, found the family plot in which he was assured Elizabeth had been laid to rest but no trace of her name on the handful of stones that occupy it. At this point just like that Christopher Robin poem about the King and the Queen who asked the Dairy Maid for butter, my friend telephoned me, I telephoned Frank Bidart, Frank telephoned Alice (Elizabeth’s relict) in San Francisco, Alice gave a shamefaced laugh and said, ‘O, I’ve been meaning to do something about that’ – ‘meaning’ for fifteen years! – so now it seems that the engraver will have to approach the polished backside of Elizabeth’s parents’ stone which is probably all to the good, since ‘awful but cheerful’ can now appear without any reflection upon them.

Of course, behind this letter, Merrill must have been thinking about his own funeral plans.

1995

More time passes. I am back in Minnesota and I open the New York Times to find Merrill’s obituary. February. Valentine’s Day is around the corner. I see teenagers shimmy up ladders to Scotch-tape streamers in gymnasiums for school dances. Lovers are placing boxes of chocolates onto double beds. The facts and newsprint tidily summarize his life. Paul Monette, poet, Aids chronicler and activist, dies four days later. I had read his book, Becoming a Man, in one sitting. A frankness about being gay was coming into the culture as never before. I thought back over my five years with Merrill: the letters, the visits, the convivial apprenticeship to the invisible art of poetry. Merrill had shown me, to use a churchy phrase, ‘radical hospitality.’

He ends ‘Christmas Tree’ with a sentence fragment: ‘Still to recall, to praise.’ Those two verbs: ‘recall’ and ‘praise’, especially at Christmas, have an Episcopal ring for me. They are familiar Episcopal words from the doxology and the Eucharist, where we ‘Praise God, from whom all blessings flow’ and ‘Recall his death, resurrection and ascension.’ Of Merrill’s sense of religion, Langdon Hammer writes: ‘there is something grand and high-stakes about Merrill’s spiritualism – he founds his own religion after all.’ That reminds me of Dickinson, the Queen Recluse, another self-made founder of her own religion. Merrill, however, made room for others, whereas Dickinson’s brand of mysticism allowed for no other living member. Merrill had made room for me. Dickinson and Merrill had found their way into the spirit world as I suppose I am doing now in my old-fashioned return to the sacristy.

2015

The sun has set on my street in Madrid where the cathedral sits. The sky is salmon-coloured and I imagine myself telling Mark about it – ‘Salmon-coloured, Mark!’ What remains curious about the dead is that they do not die. The dead surprise me, year after year now, appearing regularly, waiting for me, growing more real each time I conjure them – like on a Ouija board.

Merrill has been dead twenty years now. Hard to believe. I did become a priest. What would Merrill have thought of that? I went back to seminary. My book of poems came into the world, shockingly, after countless rejections, when I was forty-one. The call that the book would be published led, in turn, to my unlikely larger call.

I knew Merrill and his life only a little, just at the end, but I hope this sketch, this etching, adds something to our understanding of him. He was . . . I say, over and again, to those that ask after him . . . kind, generous . . . encouraging . . . loving . . . In Spanish the verb ‘amar’, for ‘to love’, is not used with the casualness it is in English. Actually, I can’t think of the last time I used it here. The verb ‘to like’, or ‘querer’, is what everyone uses in Madrid for ‘love’. In that regard the Spanish language is formal, a little detached. This was the kind of love Merrill gave to me, a little formal and detached, like I suppose the love my Spanish colleagues offer me here to keep me going with my work as the bishop’s secretary, operating in a language that is not as strong as my English. I’m talking about the kind patient smile when I have said the Spanish word incorrectly after one hundred times of saying it. I am talking about encouraging the beginner. This is love.

Featured image by Derick Leony

In-text images courtesy of Andover-Harvard Theological Library and Judith Moffett