For ten years I’ve lived in an apartment in New York City with a balcony that sits below a roof deck. The roof deck has a trellis of wisteria that blooms every May. I can only see it if I step to the edge of my balcony and peer up, but the fragrance is one of my favorite things. As the season wears on, the petals drop, so many of them that they make drifts like snow around my flower pots. I have to sweep before a rain comes because otherwise they stick. Every year I’ve thought of taking the elevator up a flight and knocking on my neighbor’s door and telling him or her (I don’t even know!) how much I love this wisteria. I’ve imagined seeing the trellis in full, in all its glory, from a different perspective. But I never have. And now this year I can’t.

For a time in Munich, I lived in a university complex for academics and their families. Again we had a little balcony and because the shared washer and drier didn’t work very well, I often used the railing to dry some of our laundry. One day I looked down and saw that a pair of my five-year-old son’s Superman underwear had dropped onto the patio of the ground floor apartment, two floors below us. I was the only resident that year who spoke only English (a huge embarrassment), and I dreaded the idea of going down to retrieve the underwear and trying to make myself understood in terrible German. I hesitated for a day or two and then the little mound of red and blue cotton was gone—and with it, an opportunity for connection, no matter how awkward.

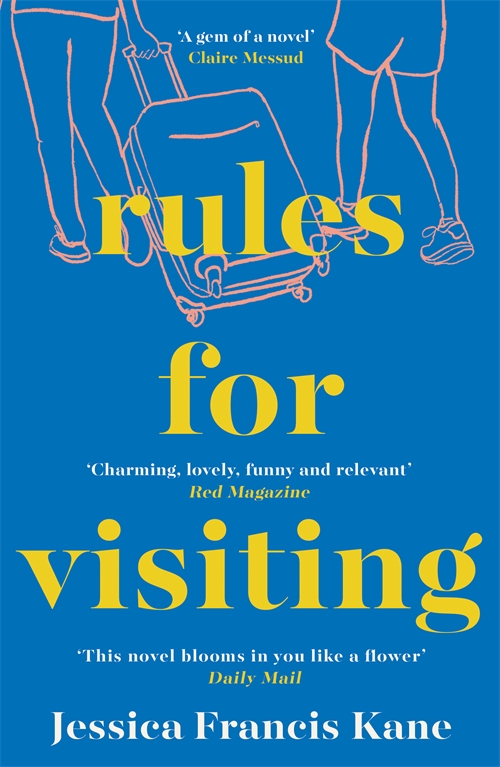

At my favorite cafe on Hudson Street there is an old pair of friends who are regulars. I suppose I am a regular in that I come to this cafe at least once or twice a week to have breakfast and write, but these two women are there every day. I always see them if I pass the place while doing other errands, and I don’t believe I have ever been there when they weren’t. One is tall, the other is short. They must be in their late seventies. We’ve shared smiles, but I’ve never said a proper hello. I put a version of them in my second novel, Rules for Visiting, and I always imagined I would tell them one day. Maybe give them copies of the book. Now this year I can’t and because of their age, I’m worried about them. Will they survive? Will the café? I don’t even know their real names.

Why have I been so ridiculous about my neighbors? Why didn’t I try harder to meet these people? Now I see videos of musicians playing for their neighbors in a building’s airshaft, or a pair of children performing a duet for their neighborhood on a front porch, or that community that is putting teddy bears in the windows for little kids to spot when they are out on a safe and socially-distanced walk, and all this neighborliness looks heavenly.

I want more. I want another chance.

I know that for every one of these heartwarming stories, there’s someone tweeting about the ‘joy’ of discovering, in the middle of a lockdown, that her neighbor is an aspiring drummer. And I share the city dweller’s deep belief that when so much space is shared, you must carve out a zone of solitude around your home to maintain sanity. This is how I explain the behavior of one of my neighbors. A few years ago, he and his sons, who had knocked with a school fundraiser, spent ten minutes walking through our apartment. He said he was curious about the floor plan, so we invited him in. He has not made eye contact with us since.

Part of the problem is the repetition, the ongoingness, of being longtime neighbors. What obligations do you have to someone you merely live near? And should that change once you’ve been invited into their space, no matter how briefly? This is something we may all wonder now that we are Zooming and FaceTiming into each other’s homes.

But my grumpy neighbor is the extreme. During Hurricane Sandy, others in my building gathered in the interior hallways during the early hours of the storm. We made a potluck of it, drank wine, let the children play far from any windows. For months afterward, we greeted each other warmly whenever we saw each other. As time wore on, those greetings got shorter and shorter. Nevertheless, we smile, note how the children have grown, catch up on bits and pieces. Eventually these snippets make up a childhood, a generation, a life. I imagine the same thing will happen with all the buildings, streets, and neighborhoods pulling together in this time. Connections are being forged, even as we keep our distance. Let’s hold onto them in the after.

To all my past neighbors, I’m sorry. To my current ones, I can’t wait to share the elevator with you again. Let’s not take out our phones before the door closes. I want to know all your dogs’ names. Let’s linger by the mailboxes (if we still have US mail) and greet each other warmly. And next May, if this pandemic is over, I’m going upstairs to knock on the wisteria gardener’s door.

Jessica Francis Kane is the author of Rules for Visiting. The paperback is published on 18 June by Granta Books and available for pre-order (UK) and out now from Penguin (US).

Cover Image © T. Kiya