One day in autumn when I had been married for less than four months I saw the landlady. I saw her in Cow Lane – such a strange place to be, cobbled selfconsciously – and when I caught sight of her I turned and pretended to be distracted by the surplus of a shop door, a banal glasspanelled door, swinging and releasing people with shopping bags.

The landlady was standing on the pavement. It had been raining, all was shining, it was mild: she was pausing and reading something on her phone. In the years since I had seen her last, when she oversaw my disgrace, she hadn’t changed. Even without preparation – nothing that had taken place during the day to indicate this encounter would occur – I felt generosity rise within me, a desire to tell her so – to tell her, you look great, you always do, you have such style. She must, I thought, be fifty now at least.

I weighed my options and eventually pivoted, prevaricated, walked away. I swept off before she could see me. My footsteps clacked on the cobblestones.

Dame Street was like coming ashore, and here I halted. I began to click the fingers of my hands. This is something I do when I want to summon a decision from within or without me. Behind, the chute leading back into Temple Bar was desultory. Buses broke from the Cathedral and brayed towards College Green.

Even now, I thought. Even now this minute I feel exhilarated to think about it, all of it, although I must confess it had been crushed into a kind of pinhead, a pinprick, a punctum, something severe, a tattoo: but when released, it was a rich green wave of memories, flaming seams and flaming seals. And at that point I hadn’t seen her, nor Harry, for something like six years. I was thirty now – over six years – although nonetheless of course I remembered it all forensically.

I was going just then to meet my husband of four months – less than four months – but found my footsteps slowed, which was strange, since typically I hurried everywhere. And there was a general slowness then, after I had seen the landlady – a distension, it was almost like horror – like everything in the environment was a sign.

I wasn’t married long. Things had happened suddenly.

I was going at that moment to meet my husband.

I continued, pressed, on my way, against the crowd, as the cathedral bells erupted and the birds scattered and gulls opened, as supple as crossbows, looking for scraps from tourists on the grass. I wondered how much I had told my husband about the episode with Harry when I was twenty-three. Little, I reckoned; hardly anything. But it had happened, certainly, to me.

It seems funny to say I have never listed the facts. This is because they make me sound foolish.

When I was twenty-three, and studying in London, I met a man who was older than me – a married man, a writer – and fell in love. Things happened suddenly then as well. We left London, this man and I, and travelled to Ireland, where I am from. We had met in April, in the first bit of mild weather; we went to Ireland in August. We came to stay in a cottage at the bottom of a tubular lane, the type in Ireland called a boreen. The cottage was his; he rented it, he knew it well.

I have taken apart every panel of this, like an ornamental fan. But we stayed in the cottage for three weeks only, just three weeks, because it was cut short you see – cut short after just three weeks, when I’d left my entire life behind.

Afterwards, for years, things brought it back to me, the cottage, suddenly: dusty aubergines; a copse against a cold bloodletting sunset in Phoenix Park; the smell of burning timber, or of damp. Once in the film institute I was folding my coat under my chair and when I sat up I could smell it – the cottage – smell smoke, wood smoke, on someone’s clothes, and I was seized with strange autonomous ecstatic grief.

I think of it in certain atmospheres. A species of spacious evening, in the countryside especially; the sky stretched and pillared, wet scents of landwater, wet dog, wet dock, steeped leaves, and earth rippled up by hooves or bicycles or boots. I remember standing in the lane barefoot, bath-time, the lustful chill and coming discomfort of nightfall – the slow rich reclamation of the fields and hills by darkness, threaded starlight, night coming on like someone filling a bucket with dark sand.

I could stay here forever! I thought. I could live on here, forever! I was young back then. I was always so wound up.

But when I saw her, the landlady, in Cow Lane, when I had been married for four months and six years had passed since it all, it was not that things came flowing back to me. In fact it had been with me, close to me, sewn into decisions like signatures, for years: redrafted, redesigned, streamlined, all confusion corrected, all forgotten details simulated, supplemented, quantified.

And so the sight of the landlady in a marvellous moss-green coat – the kind woven in Donegal and treasured for a lifetime – looking no older, looking more beautiful really, the sight of this was a source of grace or abrupt unasked-for glee. Like I had been waiting all this time to be rediscovered.

Really they are always with me, always near to hand, these memories. Image and gist maybe. Distilled.

A morning in the cottage, say. Outside the cottage: there, in the steeping lane. On this morning – I cannot capture it intact – the landlady came upon me peeing in a copse with a woollen rug on my shoulders. When I saw her I cried out to excuse myself and stood up straight. Harry was back in the bedroom, asleep.

She said, Oh dear, oh dear, the dog has run off, and I answered, I’m sure he’ll come back, and she paused at a slant as if hanging from something, her face a halfrictus of pain, so that I imagined her to be judging me, although now on reflection I think she was only distraught.

Very early. And here she was running about after the dog. As I gathered myself up I felt the sensational field of my body, and especially my fingers, expand, spreading like filaments to the broken grin of the tree trunks and growing things, the liquorsmelling richness of decay, the path churned to peaks and troughs. I felt she had brought other people with her and they were watching me. But there was nobody around.

I went back to the bedroom of the cottage then. I don’t understand how a man can sleep like that. Don’t they worry what you will do, unsupervised?

I have watched my husband, asleep, similarly: so vulnerable, so trusting, or unthinking. You could be a Judith sawing the head from Holofernes; this could be Molly’s Chamber, a girl filling a pistol up with water and inviting the magistrate in. All of these being idle thoughts of course. Freeflowing from below.

Later that same day, when Harry was once again elsewhere – working, of course – I sat on the steps as the evening fell and anxiously tried to absorb it, the lane of trees, the sounds of the breeze sifting dryly through the trees, the spokes of rowan with red berries, or to find meaning in it, to compose a deathless sentence that would explain it all to me.

I remember now that I’d felt helpless in the face of this task because I did not, for the most part, know the names of the trees.

I remember the giddiness that was a kind of declawed trauma when Harry told me, You are a complicated girl.

This is how I picture myself: as a girl, awaiting instructions, her knees drawn to her chest. A sense of aggravated static or of glittering anticipation, blackly glittering anticipation, and in such imaginings I was painfully alone. Much, much harder was the task of conjuring the man – Harry – from a distance, on mature recollection, and trying to wonder what he was thinking, if he thought about it at all, if he whipped my interest and discarded me accidentally, or without malice, without sufficient empathy – or if, really, I’d wounded him with what I’d said on that final day.

What I had said: I will not join your – chaste harem! You won’t put me back in a box like a toy.

Snottily, it must be said. Insubordinately.

On Dame Street, after I had come ashore, I turned, I walked; I watched for the landlady from the corner of my eye. My gaze alighted on the faces of people coming towards me in case I saw someone else or something else significant, in case the day was about to become a theatre of synchronicity, as days can become at times I think when fate is accelerated. I even paused and gave the street time to unfold or loosen something – I walked slowly, I thought slowly – but there were no more disclosures.

I thought, then, that I had been waiting, I had been waiting to be rediscovered – I had been waiting for him to return – for a long time, that this had been an unspoken hope and a wishful vigilance but that, since I’d met my husband, it had receded. So much so that I saw the impulse abstracted before me and felt sorry for the person who had waited, and I thought with some pleasant condescension, how does a person waste her twenties like that? The answer of course being easily indeed. As easy as can be.

Passing Essex Street I also thought of how boring life could be and of how boring people were, how inhibited, and that it was natural to conceive of wild aspirations to cope with this.

For the rest of the way I slipped into the notion that my husband might have gotten to the bus stop before me, might be waiting for me, but judged myself at the top of Parliament Street to be idiotic because he was never waiting for me. As I walked the sheer rain began to fall again, lightly, so I pulled up the hood of my coat, the coat with the tartan pattern like a picnic blanket that I became sick of suddenly and which made me feel plain. My husband was always late. He proposed to me, really, to get out of being held accountable, one evening, for being late – to get out of being held accountable for this and other things.

On the quays rain ruffled the river as the evening came on. When a bus pulled in I let it come and go, watching it lurch off and join the stalled traffic, and wondered if, one day, I would jump on a bus anyway, without my husband: if, one day, I would lose patience entirely. I saw him coming in the dark blue coat, the satchel swinging by his side, and smiling ruefully. His complexion was weathered from working, for many years, in hot weather – from living in Spain. The effect of his heavy lids was a languid expression I found restful to observe. When I saw him my irritation lifted.

Little kit, he greeted. This was the nickname he had given me. Because I am slight and I bite. Seven minutes, he said, looking at the LED screen, that’s not bad, is it?

There is power in a past, I thought, and liability too.

How was work? I asked.

My kid, he grinned, is going to win the chess tournament. He referred to the boy he had been coaching at the school where he taught history.

Oh my, I teased, you will be so fulfilled.

He can even beat me now, he said.

The grin was real; the excitement was real. He was like a child about teaching, about guiding and being seen as a guide. I always slightly disdained this since I taught third level and didn’t give a rat’s ass about it. I see now this was obvious and unhelpful.

You should come to the tournament, my husband said.

I don’t understand the rules, I retorted, because I went to state school. But then I laughed: Yes, I’ll go, I said, I’ll watch. It would be nice to see the place.

You might need to get garda vetted.

They’d want to vet me all right, state school and all of that.

I knew that he wouldn’t ask me again. I’d have to ask, and by then it would be too late to arrange anything. Because we hardly knew each other, our interdependence sometimes took the form of wary bluff and games of chicken; challenges, withholdings. But we didn’t talk much about our marriage, about the decision we’d made. We behaved as though it had always existed.

Are you all right? was something he asked me a lot. He would say this and watch me from the side of his eye. And I would pretend I did not know I was being watched.

Harry watched me, similarly, from the side of his eye.

Harry was in my mind now and weaving between my thoughts disruptively.

I remembered, standing at the bus stop I recalled, our first meal together – our first meal, Harry and I – and that it was famine food, it was cockles and mussels in broth; there were candles burning on pale pine tables, and he watched everything that I ate – tracked it, it seemed, from bowl to lips – and looked stiffly at the wineglass every time I lifted it. We were in Borough Market on a summer night. I was reading Little Dorrit at the time and I talked about how boring I was finding it. I was aware that my petulance made me look childish and guileless and attractive.

These tactics, I thought: you are tactical. The thought made me ashamed.

Standing at the bus stop, my husband placed an idle hand on the small of my back. Always this hardly calculated gesture of proprietorship has felt authentically, absorbingly, erotic to me.

I remembered Harry, spontaneously, grabbing my calf. Before me on the motorbike. Geyser of gratitude and passion at the grabbing of my calf. I knew absolutely nothing about men then, at twenty-three, but I’d learned a little since.

These two men, as I placed them alongside each other now, were not the same. My husband you see was wild with love for me, or not love for me, but a dependence that predated me and had no doubt attached itself to other women, earlier women, with a tenacity so burning it eventually burned out. Harry on the other hand had never needed me, but for in fitsandstops of anger orchestrated by my body and the way I used my body, leaving bits of it lying about, such as a leg cast out under a table outside a restaurant in Borough Market, heedless and scantily furred at the thigh where the razor had stopped. A leg thrown wide denoting hipbones open as a jaw in shock.

Harry had been a figure of awe to me. My husband, increasingly, was not: his love was a gauche and floundering type – or seemed so – full of hunger and puppyish need. To this end, the end of preserving things, my husband was also dishonest, or could be. Harry was never dishonest with me. He was smooth and contained – an image of him: the door to his office locked against me – and a canvas for huge projections, at the time, on my behalf. But I can’t, I thought then, at the bus stop, blame him for that, really.

How was the library? My husband asked me now.

Oh, fine, I said. Still on the lesser Gombrichs. I was reading, then, about illusion. I have always been interested in that.

The bus drew up. As we travelled through the city the rain began to weaken and a surprising final show of sunlight swept across the evening, leaving a red residue, so I said, we need to walk this evening – straight away, when we get home. We need to just drop all our stuff and go straight out. Before it starts raining again.

There were no free seats on the bus, only standing room swinging from poles as it dawdled north.

The old trees of the suburbs were copper and abundant. The trees at the Bishop’s palace spilled over the walls and littered the pavement with gemcoloured mulch. The landlady and her sudden exact apparition was everywhere, though nowhere substantial, and I started to wonder with application what, in fact, she might be doing now, and did she still live in the old Georgian farmhouse, and did she still rent to Harry, and did she remember me. And where he might be. I’d assumed he had gone, was in London, or somewhere else. I’d never before thought of Dublin as somewhere that Harry would manifest. I’d considered it a planet apart.

My husband sent messages from his phone, onehanded, fluently and with concentration. I looked at him. He was goodlooking. His eyes were extraordinary; his hair was still blonde, floppy if it wasn’t cut, even though he was forty now, and it all made me breathless sometimes, his body, its largeness, its mindlessly entitled occupation of space; his lips, which were full for a man, like a matinee idol, and his skin that was so weatherbeaten it betrayed, after everything, his age. A large part of my marrying him was, I reflected familiarly, for sex. He made love without skill, rutting and frank and violent, as if he’d gone without it a lot in his life, something which didn’t make sense to me. As if he hadn’t used his looks to get by or seduce. As if he hadn’t noticed them.

I first met my husband on the platform at Connolly Station, on a dry morning, at nine o’clock. I was returning from staying with my friends in Monkstown; it was a still day, the steam from the sea and the slobland at Booterstown heady. The hulk of Howth like a slab of beef. I wore the long woollen coat like a picnic blanket – the very same coat I was wearing now – and my green fingerless gloves. I sat barefaced and indifferent to the action of the morning until my train began to creep in, with a series of short faint screeches like the scraping of a plate, and at this point, abruptly, with a movement that seemed both sudden and utterly natural, a man with large pale eyes sat into the bucketseat next to me and said, this will sound weird, but can I have your number?

I was charmed, and I was rather charming at the time. You could tell from a distance that I was somewhat underoccupied. I smiled as if I had expected him to swoop into my life like that and wrote my number on a ticket with my name, Alannah, and I said, Here’s my train, I have to run!

I swept into my carriage like a girl in a film. I didn’t turn to watch him wave or read the number and my name as it drew off because I felt bashful; I went into the bathroom, allowing the slow suckerdoor to seal behind me, and looked at myself in the mirror instead. He didn’t call until the following day, and in the interim I became concerned that he had forgotten me, when I had already begun to grow fond of the origin story – of the station, the train, the great icy frightening eyes – which sounds even now like something I made up.

When he did call I rode my bike to Botanic Avenue to meet him from work, cockily apprehensive, and for a few minutes we couldn’t speak. After two more coffee dates in quiet rhapsody the ceiling began to recede.

I loved. It is simple. There was nothing to stop me. I really didn’t have anything else on.

When I was in London, years before – when I met Harry – I was a little similarly idle, bored – I had lots to do, but I felt disconnected from these obligations – and this is probably not a coincidence. There was no one to stop me falling in either case because no one was watching me. Because I was quite typically and ardently alone most of the time. As I have always been.

The man from the platform and I walked, on our third date, to the botanical gardens. We strolled through the palm house, by the blue fins of succulents, the cacti like torture implements. We were careful and cool and witty with one another. Or I was. At length I said, Well now, what is it that you have to say to me? Why weren’t you free on Friday night?

A little longer, he replied.

Outside the sun was bright, the trees in high relief. As we walked under an avenue of trees, past grandparents with prams and toddlers, he put his arms around me for the first time, drawing me close to him with emphasis, gripping my hip.

Tell me, I commanded. Are you married? On the run from the law? OK, it isn’t funny now.

He pushed his face into my hair. For a moment or two we hung there, before he asked if we could sit, and we found a bench overlooking a slant of silver birches spaced apart.

I think that when I tell you this, he said, you will get up and run. He was clinging to me and looking ahead.

Jesus. I tried to lighten him. What are you, an assassin?

He said nothing but planted a kiss on my temple. We had not gone to bed yet and this was the closest, physically, we’d been. He was pressing fingers softly on the bars and hollows of my ribs – pressing ribs, glaring bleakly ahead – and I thought with a spike of surprise about Harry’s hands, pressing and counting the very same bars and hollows of my ribs. This thought, like a ghost in daylight, faded out. Faded out of sight only, that is; remained, otherwise, in a kind of waiting way.

Tell me, I commanded, because I am starting to think that you are married. I thought, oh God. There is nothing new under the sun.

I’m not married, he said. Then quietly, shutting his eyes, I am father to a little girl. She is less than a year old.

Are you living with her mother? I asked at once.

No.

But you know each other?

We’ve been involved, on and off, for years.

But not now.

We hardly speak without arguing. But. He looked around. If one of her brothers came by and saw me now, he would break out the hurley, if you know what I mean.

She is not, he added, my only child. When I was at college, he said, my girlfriend got pregnant. I have another daughter, she’s a teenager, and she grew up abroad.

Well you’re older than me, I said slowly, in shock. I suppose history is inevitable. I have history, I said. I thought, privately, that my history just then looked less substantial, less fleshy, than partners, children, and duties; than the exotic word abroad. My history was, rather, an emotional undulation without a name. I found this thought unpleasantly humbling.

Close to us a rideon mower was grinding and blowing shards of grass to the air; the birches trembled delicately; the sky was clear. He was holding fast to me now and asking, do you want to run? Do you want to leave now?

But of course I did not want to run because I was intrigued. I saw myself even then as the very flower of generosity, petals aching open in reception, affection, and grace; we had passed through the palm house, clammy and airtight and safe; I saw complexity and delicacy under a bell jar. Also I thought, well, none of this is really my problem, is it?

Well I’ll have to think, I said. Do you want to walk me to my bike?

At this, the man laughed with relief, shaking his head and looking at me; repeating, Walk you to your bike, saying, But won’t you stay a bit longer?

I’ve got to go, I told him. It’s late enough. I rode into town as the evening approached. Spring was coming, and it would be a beautiful one.

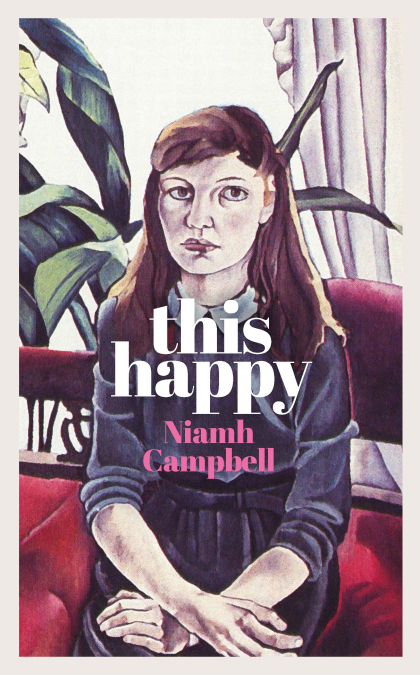

Photograph © A Ryan

Niamh Campbell’s debut novel This Happy is available now.