Nirmala Chakravarty, a young and beautiful Shakta mystic from East Bengal, known to her followers as Anandamayi, first came to the city of Benares in 1928. A ceaseless traveller, she was to make it a home of sorts (as Shiva’s city, Benares is of special importance to Shaktas, who are followers of Shiva’s female companion, Durga), and gathered a large and devoted following. In the early 1940s, a few years after her husband died, she established in the city an ashram for young girls, a kanyapeeth. It was by no means usual for a woman – still less a widow – to penetrate the maze of this most sacred Hindu city. Ashrams were a monopoly of male gurus, with strict rules of initiation and discipleship, and residents were nearly always male. Anandamayi’s kanyapeeth was – and remains – probably unique in India.

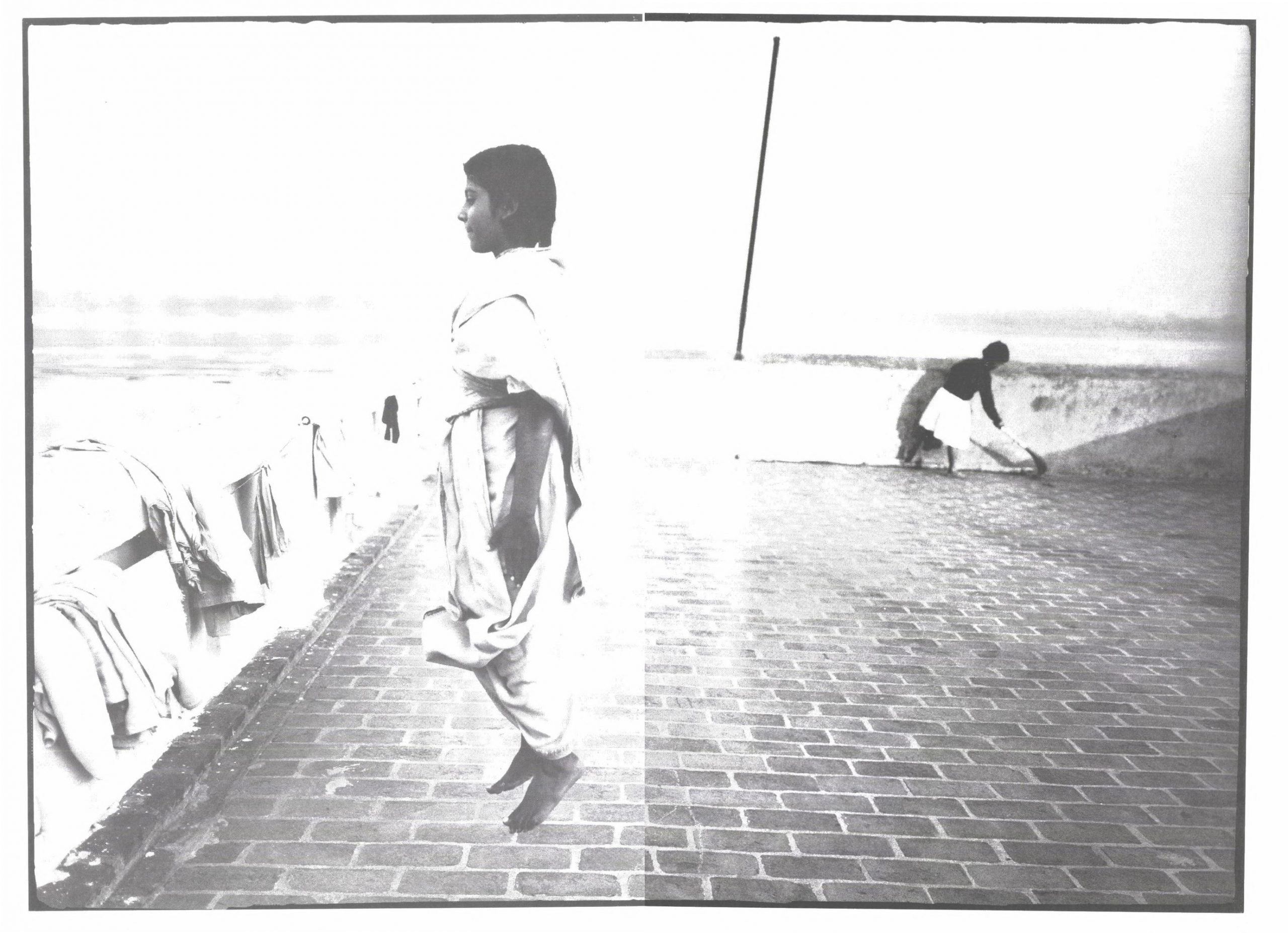

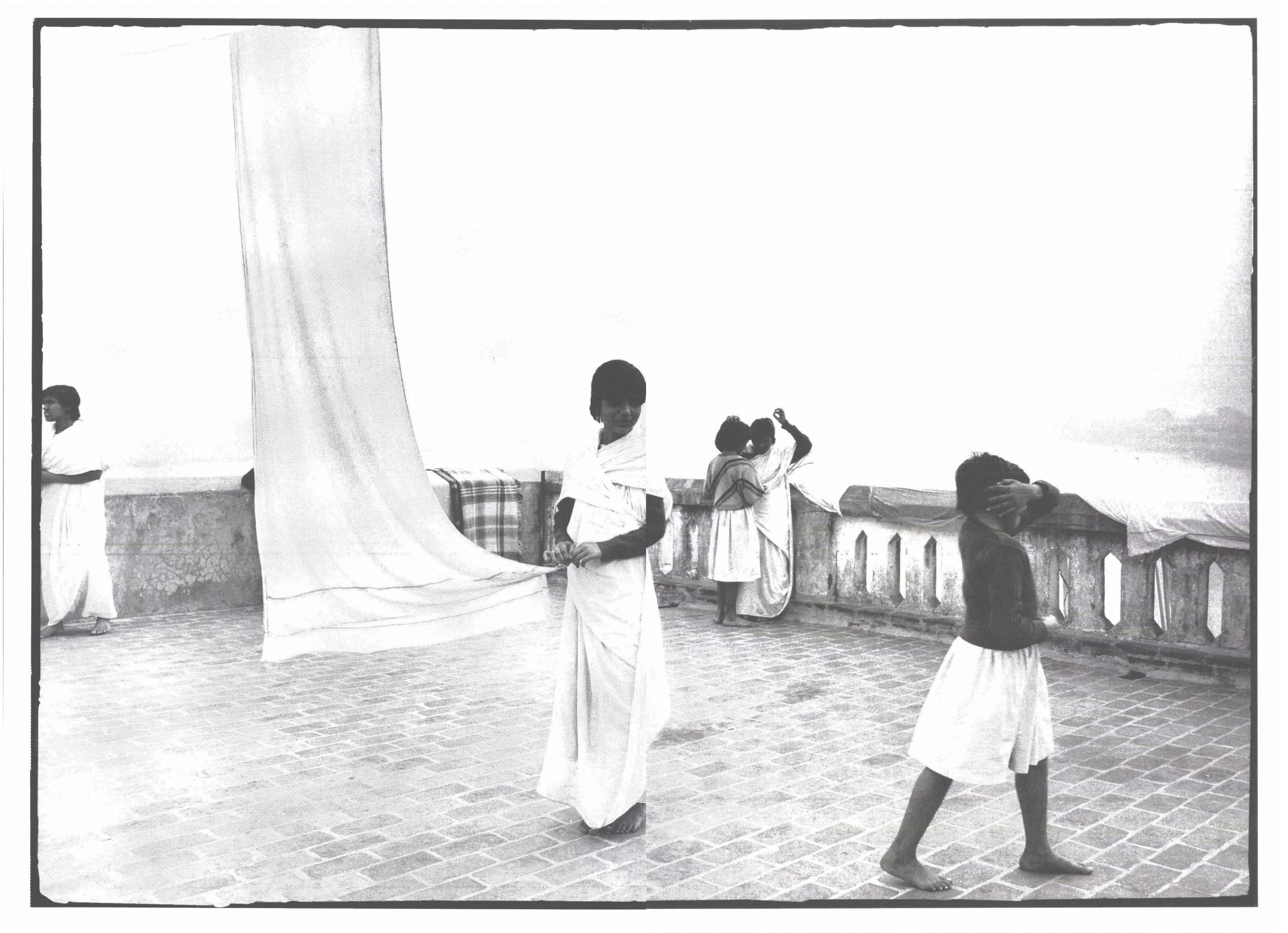

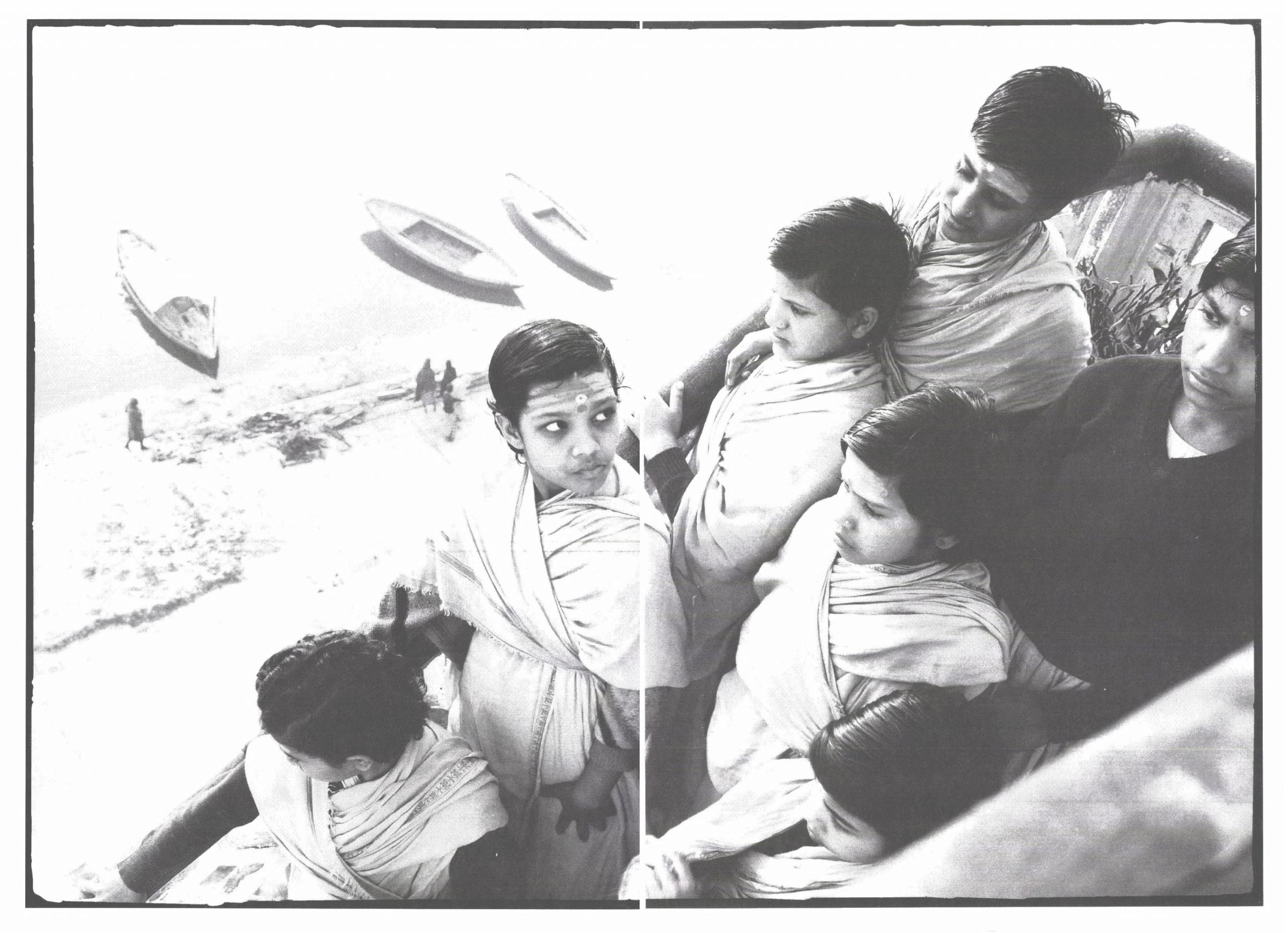

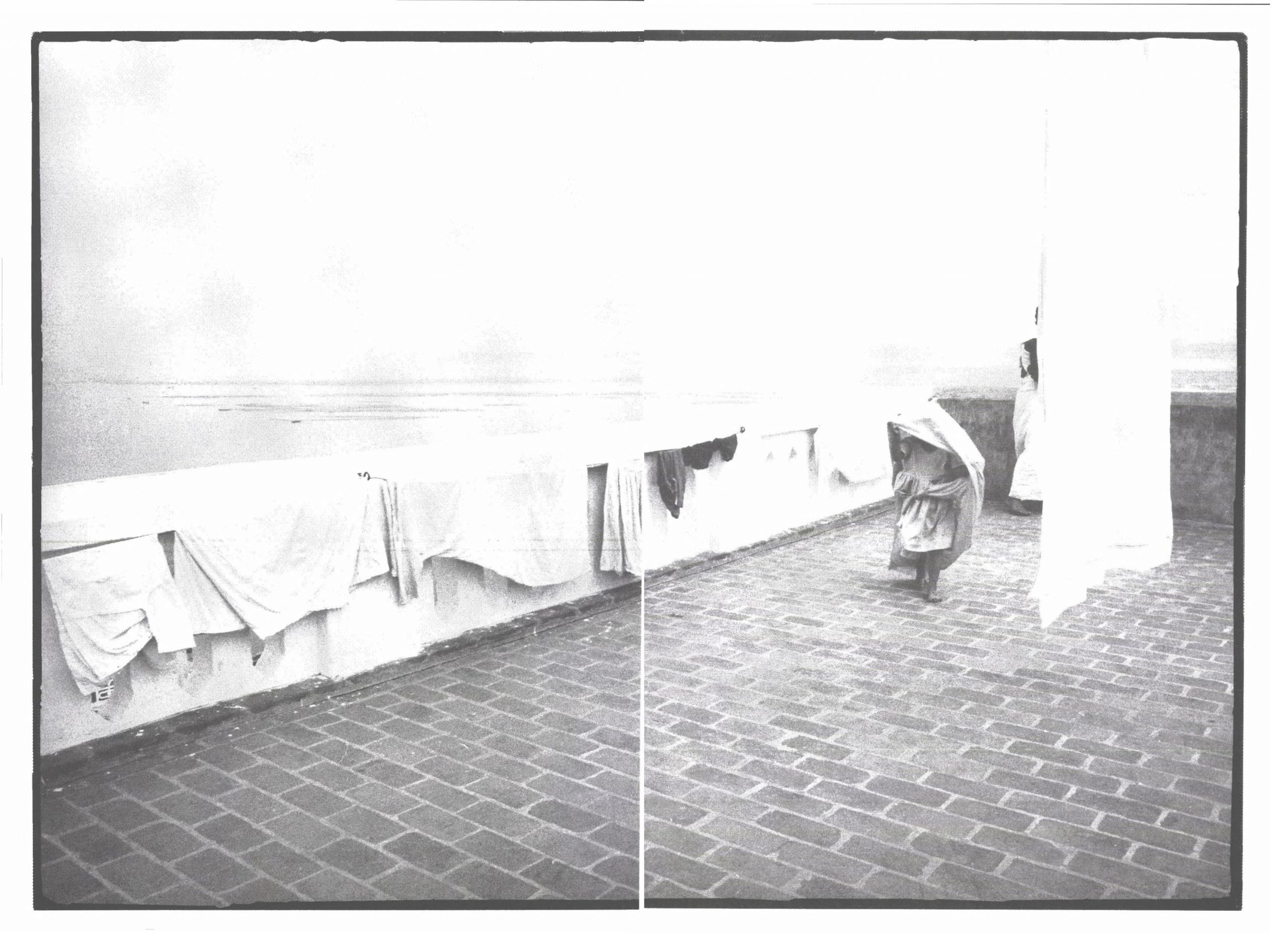

The ashram, a massive abutment of stone walls, white stucco courtyards, rooms, canopies and terraces, with sweeping views across the city and river, was built high above the Ganges just beyond Asi Ghat, where the river begins its long, slow bend northwards. The land was given to Anandamayi by the Maharaja of Benares – he and his sister had become devotees – and the big stone steps that lead down from the ashram to the river were named Anandamayi Ghat. In this most clamorous of cities, busy with the traffic of migrant souls and the display of every aspect of life and death, the ashram became a very private, secluded world.

Anandamayi died in 1982. Over the course of her long life, she counted devotees among the poorest as well as among India’s elites. One of her most famous followers was Kamala Nehru – wife of the agnostic Jawaharlal Nehru, and mother of Indira Gandhi. Indira Gandhi herself, from time to time, would turn to Anandamayi for talismans and spiritual relief: indeed, when Mrs Gandhi was sworn in as Prime Minister for the first time in 1966, she made it a point to wear a rudrakshamala – a necklace of special wooden beads – given to her by Anandamayi.

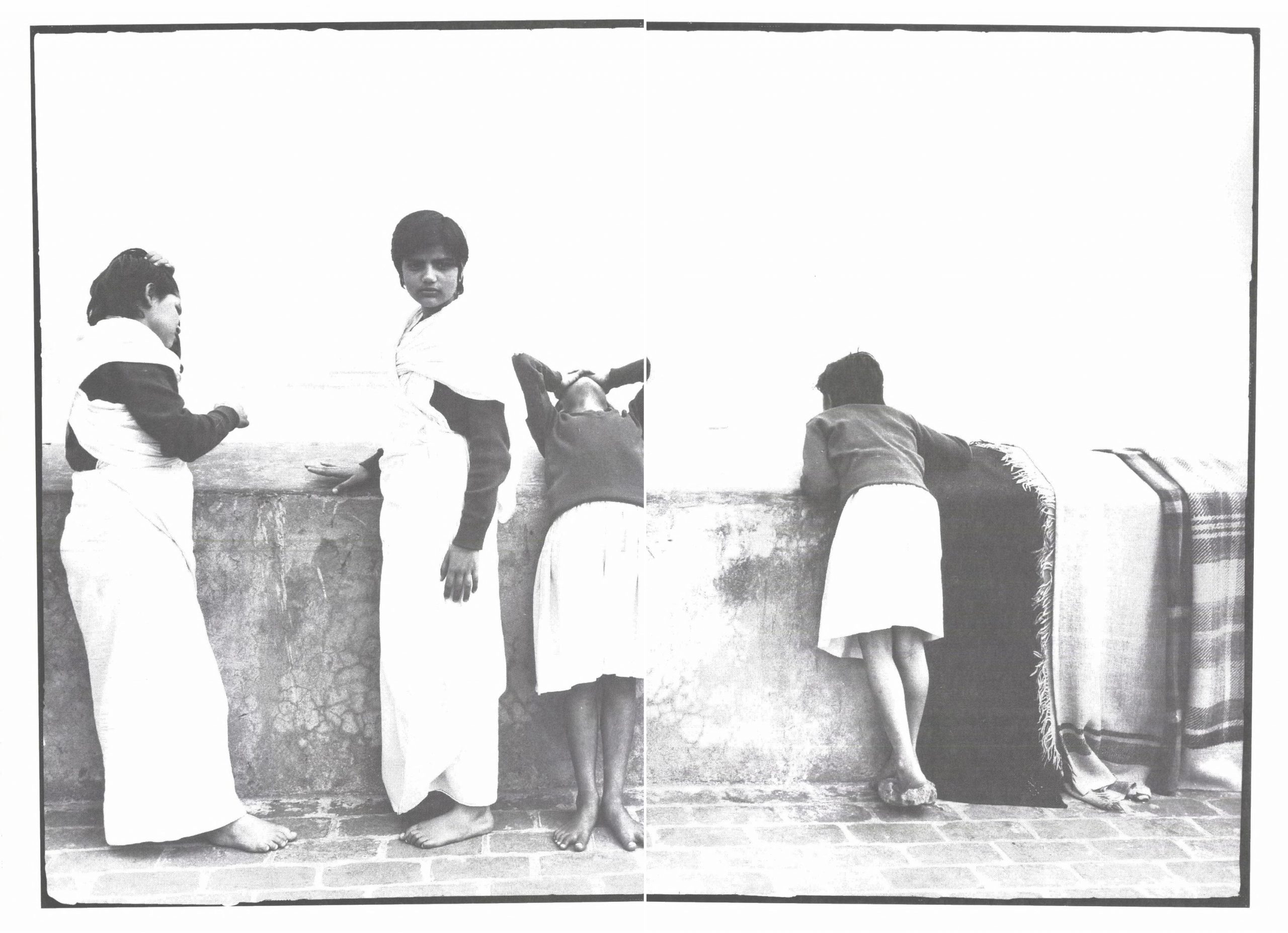

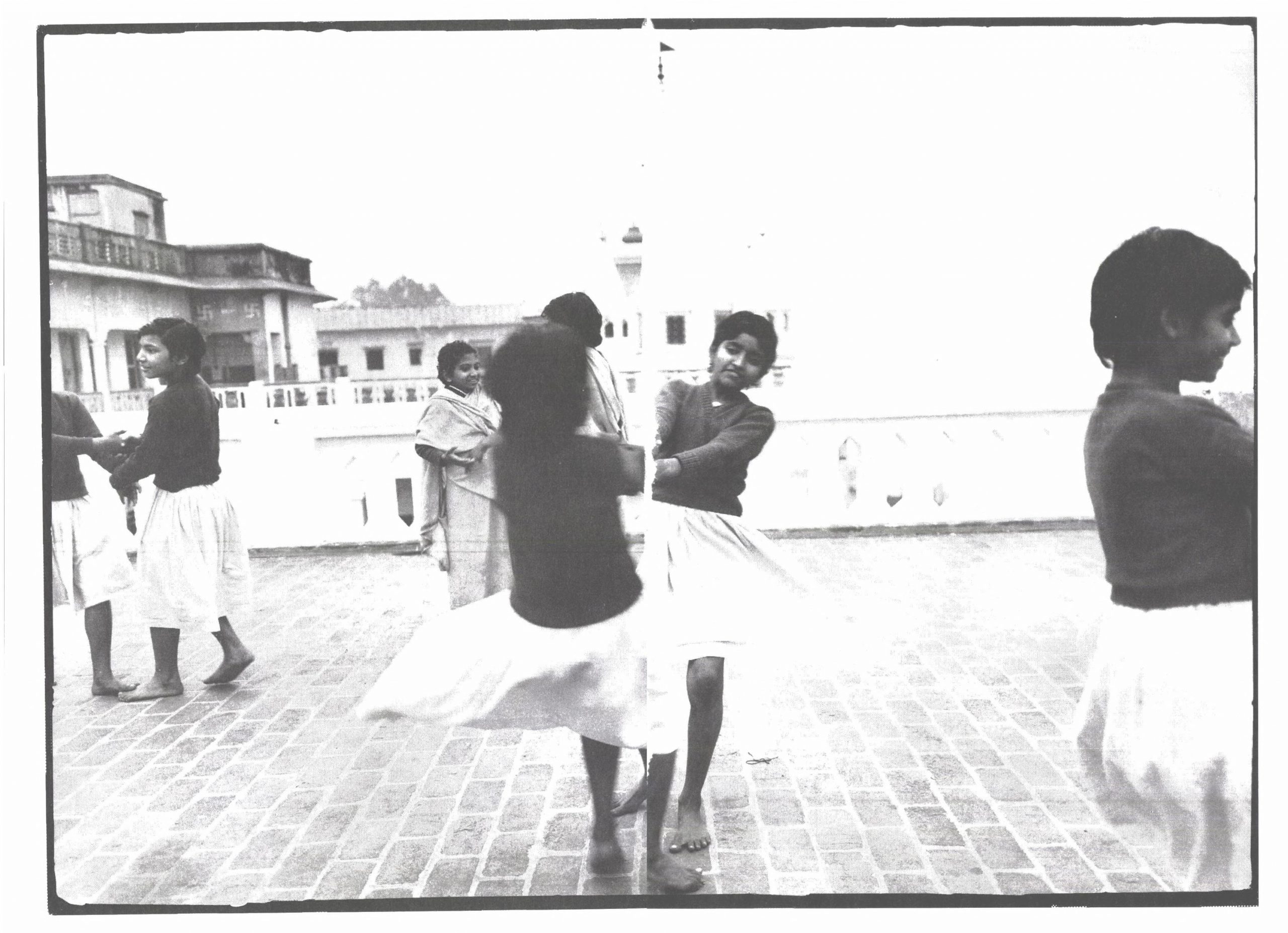

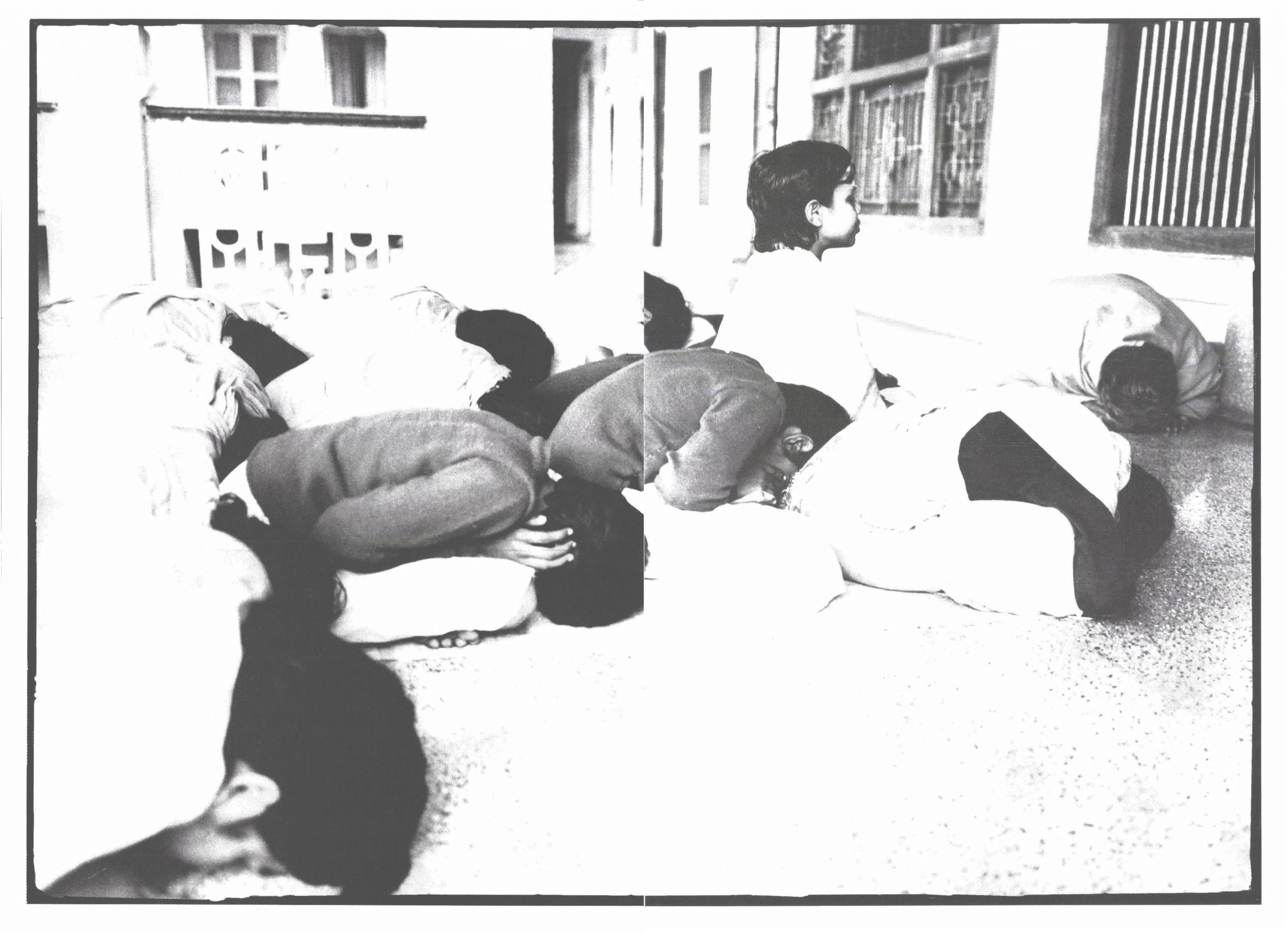

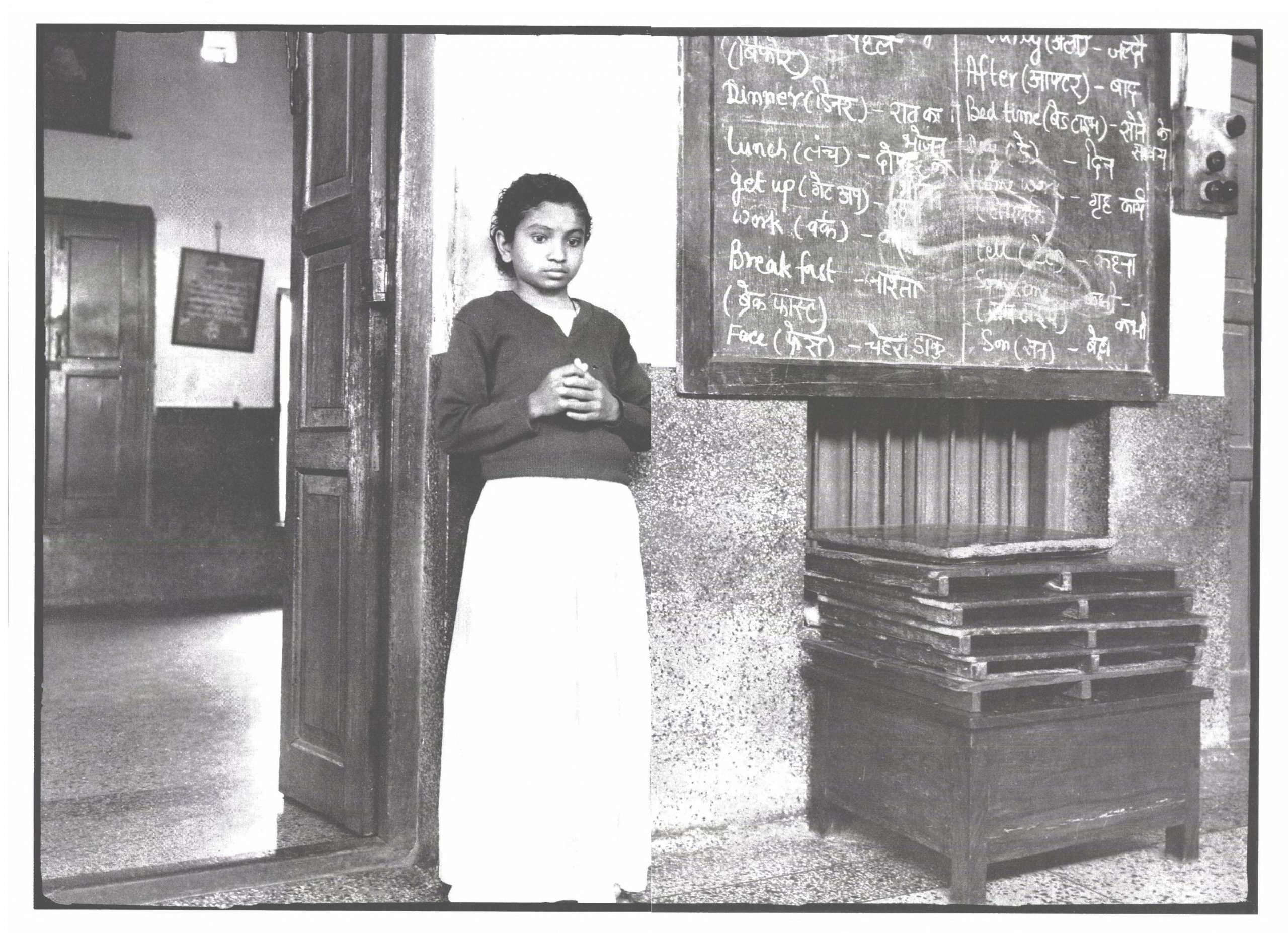

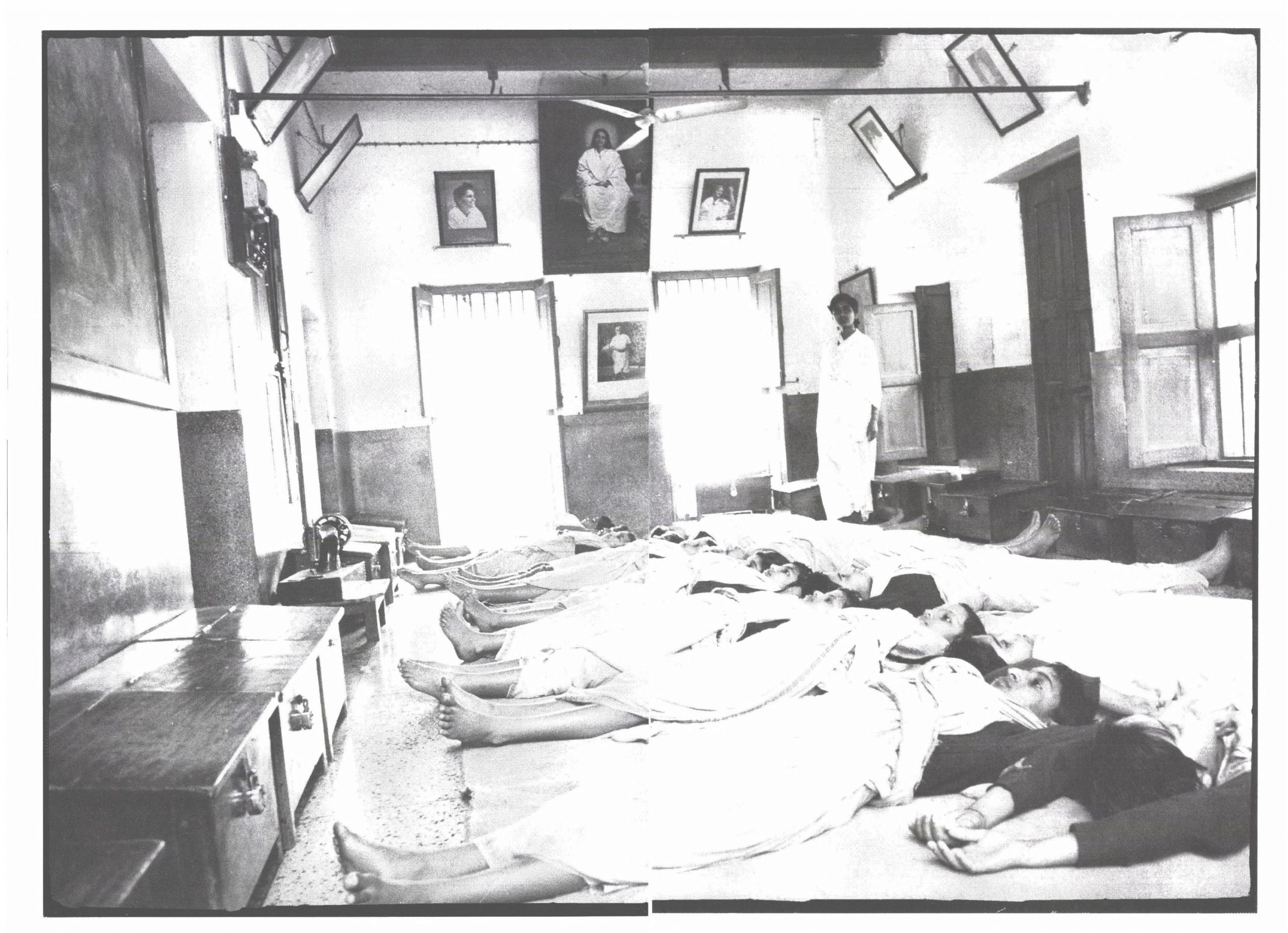

The ashram Anandamayi founded has survived her death. Today it houses around forty girls, many of them sent there by their parents in Bengal, and half a dozen senior disciples who instruct and teach them. The girls, who know Anandamayi as Ma, can enter the ashram from the age of six; when they reach eighteen they are free to decide whether to remain there and renounce the world or return to it – as most in fact do. The days begin early, at 4 a.m., with Arati ceremonies – the lighting of oil lamps and singing (the singing carries on throughout the day; that, and the laughter of the girls, is a regular sound), and some formal lessons – in recent years they have started to learn English. The girls attend to everything themselves: cleaning, laundry, cooking (good Bengali vegetarian food without passion-stimulating onions or garlic, all cooked on coal fires). There is no radio, television or newspapers and the girls rarely leave the ashram. One occasion when they do is an annual journey by boat to the Maharaja’s palace in Ramnagar. But every day, from their terraces, they can watch the world: burning pyres, marriage ceremonies, children playing, the sunrise across the river. Most visitors to Benares know nothing of the girls’ existence. Only from a boat on the river can you sometimes see their hands waving, small and excited, from the terrace.

Outsiders do come to the ashram – but they are confined to the public courtyard and are not given access to the interior where the girls live, learn and play. Until now, the only photographs taken at the ashram have been of its public areas – most notably by that great observer of Benares, Richard Lannoy. Looking at the photographs taken by him, fifty years ago, and those taken by Dayanita Singh in 1998, the constancy of the girls is remarkable: the same cropped hair, bright eyes, a scampish grace.