My life began in February 1930. I got ready in the summer of 1929, by leaving college at the end of my junior year, against my father’s will, and running through two jobs, proof that I could make my way and pay for it if I didn’t mind a diet of doughnuts and pawning my typewriter to tide me over weekends. 1930 was the real thing. I persuaded the Holland America Line to give me free passage in steerage, then described as Student Third Class, in return for a glowing article to use in their trade magazine. Aged twenty-one, with a suitcase and about seventy-five dollars, I set off for Paris, where I knew nobody – a joyful confident grain of sand in a vast rising sandstorm. I had visited Paris twice before and it was not my dream city, but I intended to become a foreign correspondent within a few weeks, and Paris was the obvious place to launch my career.

The launch lacked a certain savoir-faire. The flower stalls at the Place de la Madeleine suited my liking for a pretty neighbourhood. On a nearby side street I found a hotel, no more than a doorway, a desk and dark stairs, and was gratified by the price of the room. The room was smelly and squalid and I thought it impractical to have a mirror on the ceiling but perhaps that was a French custom. There was an amazing amount of noise in the corridors and other rooms but perhaps the French did a lot of roaming in hotels. I could not understand why the man at the desk grew more unfriendly each time he saw me, when I was probably the friendliest person in Paris.

Having checked the telephone directory, I presented myself at the office of the New York Times and informed the bureau chief, a lovely elderly Englishman aged maybe forty, that I was prepared to start work as a foreign correspondent on his staff. He had been smiling hugely at my opening remarks and mopped up tears of laughter when he learned where I lived. He took me to lunch – my enthusiasm for free meals was unbounded – and explained that I was staying in a maison de passe, where rooms were rented by the hour to erotic couples. My new English friend insisted that I change my address, and bribed me with an invitation to report next week again at lunch. He suggested the Left Bank; I would be safer in the students’ milieu.

The private life of the French was their own business and no inconvenience to me, but I was offended by the unfriendliness of the man at the hotel desk. I got off the Métro at Saint Germain des Prés, thinking it would be nice to live in fields if not near flowers, and was sorry to find no fields but did find a charming little hotel on the rue de l’Université, which no doubt meant a street for students. This hotel was also cheap, and a grand piano, with a big vase of flowers on it, filled the tiny foyer. My windowless room had a glass door opening onto an iron runway. The bath, at extra cost, was four flights down in the courtyard. I thought it remarkable that young men, the other residents, cried so much and quarrelled in such screeching voices, but I liked the way they played Chopin on the grand piano and kept fresh flowers in the big vase.

An ex-Princetonian, studying at the Beaux Arts, a throwback to my college days, came to collect me for dinner one night and was ardently approached by a Chopin pianist, and scandalized. He explained homosexuality, since I had never heard of it. I pointed out that I could hardly be safer than in a homosexual hotel and, besides, I was sick of people butting in on my living arrangements. I won and lost jobs without surprise and saved up, from my nothing earnings, so that I could eat the least expensive dish at a Russian restaurant where I mooned with silent love for a glorious White Russian balalaika player.

The years in France and adjacent countries were never easy, never dull and an education at last. Unlike the gifted Americans and British who settled in Paris in the twenties and lived among each other in what seems to me a cosy literary world, I soon lived entirely among the French, not a cosy world. The men were politicians and political journalists; the students of my generation were just as fervently political. Money depended on age; the old had it, some of them had lashings of it; the young did not.

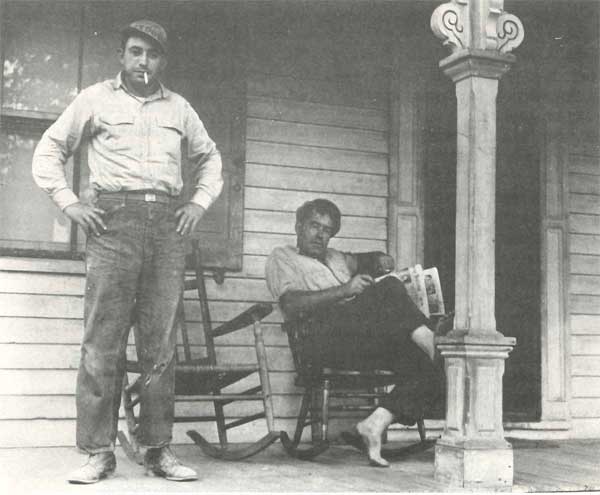

I was astonished, a few years later in England, to meet young men who neither worked nor intended to work and were apparently rich. A combination of the English eldest son syndrome and the time-honoured method of living on debts, charm and hospitality. They were much more fun than the French, but I thought them half-witted; they knew nothing about real life. Real life was the terrible English mill towns, the terrible mining towns in northern France, slums, strikes, protest marches broken up by the mounted Garde Républicaine, frantic underpaid workers and the frantic half-starved unemployed. Real life was the Have-nots.

The Haves were sometimes enjoyable, generally ornamental and a valuable source of free meals and country visits. I did not recognize the power of the Haves. Because of my own poverty, fretting over centimes, make-do or do-without, keeping up my appearance on half a shoestring, I absorbed a sense of what true poverty means, the kind you never choose and cannot escape, the prison of it. Maybe that was the most useful part of my education. It was a very high-class education, all in all, standing room at ground level to watch history as it happened.

During the French years, I returned to America once in 1931. This period is lost in the mists of time. I know that I travelled a lot and began the stumbling, interminable work on my first novel. (When it finally appeared, in 1934, my father read it and said, rightly, that he could not understand why anyone had published it. I have, also rightly, obliterated it ever since.) With a French companion in the autumn of 1931, I made a long hardship journey across the continent from the east to the west coast. It was all new and exotic to him, not to me, and I remember very little.

Suddenly, one sunny morning in London in 1936, I was to remember a lynching in Mississippi, and ‘Justice at Night’ wrote itself as if by Ouija board. I was cadging bed and breakfast from H.G. Wells; cadging room from those who had it was a major occupation of the moneyless young in those days. Wells nagged steadily about my writing habits; a professional writer had to work every morning for a fixed number of hours, as he did. Not me. I dug in solitude like a feverish mole until I had dug through to the end, then emerged into daylight, carefree, ready for anything except my typewriter; until the next time. I had just finished my book on the unemployed, The Trouble I’ve Seen, and spent the London nights dancing with young gentlemen of my acquaintance and was not about to adopt Wells’s 9.30 a.m. to 12.30 p.m. regime. Not then or ever. That morning, to show him I could write if I felt like it, I sat in his garden and let ‘Justice at Night’ produce itself. Wells sent it to the Spectator. I had already moved on to Germany where I ceased being a pacifist and became an ardent anti-fascist.

Late in 1934, in Paris, it dawned on me that my own country was in trouble. I thought that trouble was a European speciality. America was safe, rich and quiet, separate from the life around me. Upon finally realizing my mistake, I decided to return and offer my services to the nation. Which I did on a miserable little tub of the Bernstein Line, price of passage eighty-five dollars; arriving in New York on 10 October. By 16 October I was enrolled in the service of the nation.

I wore the only clothes I had, a Schiaparelli suit in nubbly brown tweed fastened up to its Chinese collar with large brown leather clips, and Schiap’s version of an Anzac hat in brown crochet-work adorned by a spike of cock-pheasant feathers. I could not afford to buy clothes in the ordinary way and dressed myself in soldes, the bargain discarded outfits that the models of the great couturiers had worn in their last collections. Also I painted my face like the Parisian ladies, lots of eyeshadow, mascara and lipstick, which was not at all the style for American ladies then, and certainly not for social workers in federal employment. Mr Hopkins may have been entertaining himself. He could sack me at any moment and was not delving deep into the public purse, though to me the job meant untold riches: seventy-five dollars a week, train vouchers and five dollars per diem travel allowance for food and hotels.

For three weeks short of a year, I crossed the country, south, north, east, midwest, far west, wrote innumerable reports and kept no copies, the chronic bad habit of my professional life. A few years ago, someone found six of my early reports in Mrs Roosevelt’s papers at the Hyde Park Roosevelt Library. I have cut and stuck three together below because I think they are a small but vital record of a period in American history. They were not written for publication, they can hardly be called written; banged out in haste as information.

After a few months, I was so outraged by the wretched treatment of the unemployed that I stormed back to Washington and announced to Mr Hopkins that I was resigning to write a bitter exposé of the misery I had seen. I did not pause to reflect that I had no newspaper or magazine contacts and was unlikely to create a nationwide outcry of moral indignation. Instead of telling me not to waste his time, Mr Hopkins urged me to talk to Mrs Roosevelt before resigning; he had sent her my reports. I walked over to the White House, feeling grumpy and grudging. Mrs Roosevelt, who listened to everyone with care, listened to my tirade and said, ‘You should talk to Franklin.’

That night I was invited to dinner at the White House, seated next to the President in my black sweater and skirt (by then I was rich enough to buy ordinary clothes), and observed in glum silence the white-and-gold china and the copious though not gourmet food, hating this table full of cheerful well-fed guests in evening clothes. Didn’t they know that better people were barefoot and in rags and half-starved; didn’t they know anything about America?

Mrs Roosevelt, being somewhat deaf, had a high sharp voice when talking loudly. She rose at the far end of the table and shouted, ‘Franklin, talk to that girl. She says all the unemployed have pellagra and syphilis.’ This silenced the table for an instant, followed by an explosion of laughter; I was ready to get up and go. The President hid his amusement, listened to the little I was willing to say – not much, suffocated by anger – and asked me to come and see him again. In that quaint way, my friendship with the Roosevelts began and lasted the rest of their lives. Mrs Roosevelt persuaded me that I could help the unemployed more by sticking to the job, so I went back to work until I was fired, courtesy of the FBI.

I think I know what happened now, though I had a more grandiose explanation at the time. In a little town on a lake in Idaho called Coeur d’Alene, pronounced Cur Daleen, I found the unemployed victimized as often before by a crooked contractor. These men, who had all been small farmers or ranchers on their own land, shovelled dirt from here to there until the contractor collected the shovels, threw them in the lake and pocketed a tidy commission on an order for new shovels. Meantime the men were idle, unpaid and had to endure a humiliating means test for direct dole money to see them through.

I had never understood the frequent queries from Washington about ‘protest groups’. I thought Washington was idiotic – they didn’t realize that these people suffered from despair, not anger. But I was angry. By buying them beer and haranguing them, I convinced a few hesitant men to break the windows of the FERA office at night. Afterwards someone would surely come and look into their grievances. Then I moved on to the next stop, Seattle, while the FBI showed up at speed in Coeur d’Alene, alarmed by that first puny act of violence. Naturally the men told the FBI that the Relief lady had suggested this good idea; the contractor was arrested for fraud, they got their shovels for keeps, and I was recalled to Washington.

I wrote to my parents jubilantly and conceitedly: ‘I’m out of this man’s government because I’m a “dangerous Communist” and the Department of Justice believes me to be subversive and a menace. Isn’t it flattering? I shrieked with laughter when Aubrey [Williams, Mr Hopkins’s deputy] told me; seems the unemployed go about quoting me and refuse – after my visits – to take things lying down.’

While I was collecting bits and pieces from my seldom-used desk in the Washington FERA office, the President’s secretary rang with a message from the President. He and Mrs Roosevelt, who was out of town, had heard that I was dismissed and were worried about my finances because I would not find another government job with the FBI scowling, so they felt it would be best if I lived at the White House until I sorted myself out. I thought this was kind and helpful but did not see it as extraordinary – a cameo example of the way the Roosevelts serenely made their own choices and judgements.

Everyone in the FERA office was outdone by the stupid interfering FBI; I treated the whole thing as a joke. Naturally the Roosevelts, the most intelligent people in the country, knew it was all nonsense, though, being the older generation, they considered the practical side. I had saved enough money for time to write a book, but had not planned where to work and the White House would be a good quiet place to start. It was, too, but I needed the complete mole existence for writing and departed from the White House with thanks and kisses as soon as a friend offered me his empty remote house in Connecticut. Being fired was an honourable discharge in my view, not like quitting; and I was very happy to work on fiction again. When I finished the book, I went back to Europe, having done my duty by my country.

That was the time when I really loved my compatriots, ‘the insulted and injured’, Americans I had never known before. It was the only time that I have fully trusted and respected the American Presidency and its influence on the government and the people. Now it is accepted that Franklin Roosevelt was one of the rare great Presidents. While he was in office, until America entered the war, both the Roosevelts were daily vilified and mocked in the Republican press, and both were indifferent to these attacks. Mrs Roosevelt was in herself a moral true north. I think the President’s own affliction – he was crippled by polio at the age of thirty-nine – taught him sympathy for misfortune. They were wise. They had natural dignity and no need or liking for the panoply of power. I miss above all their private and public fearlessness.

Born to every privilege that America can offer, they were neither impressed by privilege nor interested in placating it. The New Deal, the Roosevelt regime, was truly geared to concern for the majority of the citizens. I am very glad that I grew up in America when I did and glad that I knew it when the Roosevelts lived in the White House. Superpower America is another country.

I went to Spain in March 1937 and became a war correspondent by accident. From then on, until 1947, I wrote no journalism except war reports, apart from four articles in 1938. Collier’s, my employer, cabled me in Barcelona asking me to go to Prague. In war, I never knew anything beyond what I could see and hear, a full-time occupation. The Big Picture always exists, and I seem to have spent my life observing how desperately the Big Picture affects the little people who did not devise it and have no control over it. I didn’t know what was happening around Madrid and certainly not what was happening in Czechoslovakia, but now I had suddenly at long last become a foreign correspondent.

I went to Czechoslovakia when the Czechs were mobilized and determined to fight for their country against Hitler; I went the second time after the Munich Pact. In between, at Collier’s request, I went to England, because my editor wanted some idea of the English reaction to oncoming war. I had already done a similar article about France. I found the mental climate in England intolerable; sodden imagination, no distress for others beyond the sceptr’d isle.

Three days before he flew to Berchtesgaden to sign away the life of Czechoslovakia, the Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, a stick figure with a fossil mind, addressed the nation by radio, speaking to and for the meanest stupidity of his people: ‘How horrible, fantastic, incredible it is that we should be digging trenches and trying on gas masks because of a quarrel in a faraway country between people of whom we know nothing.’ Then he came back from Germany, waving that shameful piece of paper and proclaiming ‘peace with honour’ to the cheering crowds. This same government had starved the Republic of Spain through its nefarious Non-intervention Treaty, while Hitler and Mussolini were free to aid Franco. I thought the only good British were in the International Brigade in Spain; I was finished with England, would never set foot again in the miserable self-centred country. Instead of which, since 1943, London has been the one fixed point in my nomadic life.

At the end of the decade, in December 1939, I was again in Paris on my way home to Cuba from the Russo-Finnish War. Czechoslovakia and Spain were lost and I knew I was saying goodbye to Europe. I did not think it was a phoney war; I thought it would be a hell-on-earth war and a long one. Having started off in this city, so merry and so ignorant almost ten years before, here I was despairing for Europe and broken-hearted for Spain. The powers of evil and money ruled the world.

Now brave men and women, anti-fascists all over Europe, would be prey for the Gestapo. I had not then taken in the destiny planned for the Jews. Perhaps this was because in Germany in the summer of 1936 there were no startling signs of persecution, not when Nazi Germany was host to the Olympic Games, and on its best behaviour. I was obsessed by what Hitler was doing outside his country, not inside Germany. To me, Jews and anti-fascists were the same, caught in the same trap, equally condemned. Passports were the only escape. None of the people I knew and cared for had passports, or anywhere to run. I saw them all as waiting for a sure death sentence, unsure of the date of execution.

Paris was beautiful and peaceful in the snow, peacefully empty. Men I had known in the early thirties, now important people, ate in grand restaurants and told me not to be so sad and foreboding. Cheer up, we have the Maginot Line. I owned an invaluable green American passport. I was perfectly safe; I even had some money in the bank because Collier’s paid generously. I felt like a profiteer, ashamed and useless. By geographical chance, the piece of the map where I was born, I could walk away. I had the great unfair advantage of choice.

I think I learned the last lesson of those educational years unconsciously. I had witnessed every kind of bravery in lives condemned by poverty and condemned by war; I had seen how others died. I got a measure for my own life; whatever its trials and tribulations, they would always be petty, insignificant stuff by comparison.

Martha Gellhorn’s Letters to the Federal Emergency Relief Administration

Washington, DC

11 November 1934

My Dear Mr Hopkins,

I came in today from Gastonia, North Carolina, and was as flat and grim as is to be expected. I got a notice from your office asking about ‘protest groups’. All during this trip in both Carolinas I have been thinking to myself about that curious phrase ‘red menace’, and wondering where said menace hid itself. Every house I visited – mill worker or unemployed – had a picture of the President. These ranged from newspaper clippings (in destitute homes) to large coloured prints, framed in gilt cardboard. The portrait holds the place of honour over the mantel; I can only compare this to the Italian peasant’s Madonna. I have seen people who, according to any standard, have practically nothing in life and practically nothing to look forward to or hope for. But there is hope, confidence, something intangible and real: ‘The President isn’t going to forget us.’

I went to see a woman with five children who was living on relief ($3.40 a week). Her picture of the President was a small one. Her children have no shoes and the woman is terrified of the coming cold. There is almost no furniture left in the home, and you can imagine what and how they eat. But she said, suddenly brightening, ‘I’d give my heart to see the President. I know he means to do everything he can for us, but they make it hard for him; they won’t let him.’

In many mill villages, evictions have been served; more threatened. These men are in a terrible fix. (Lord, how barren the language seems: these men are faced by the prospect of hunger and cold and homelessness and of becoming dependent beggars – in their own eyes. What more a man can face, I don’t know.) You would expect to find them maddened with fear, with hostility. I expected and waited for ‘lawless’ talk, threats, or at least blank despair. And I didn’t find it. I found a kind of contained and quiet misery; fear for their families and fear that their children wouldn’t be able to go to school. What is keeping them sane, keeping them going on and hoping, is their belief in the President.

Boston, Massachusetts

26 November 1934

My Dear Mr Hopkins,

It seems that our [relief] administrators are frequently hired on the recommendations of the Mayor and the Board of Aldermen. The administrator is a nice inefficient guy who is being rewarded for being somebody’s cousin. The direct relief is handled by the Public Welfare which is a municipal biz and purely political in personnel. I can’t very well let myself go about the quality of these administrators; they are criminally incompetent.

In one town the [relief] investigators (who are supposed to be doing some social work) are members of the Vice Squad who have been loaned for the job. Usually there is only one investigation at the office (followed by a perfunctory home visit) to establish the eligibility of the client for relief. I can’t see that these questions do anything except hurt and offend the unemployed, destroy his pride, make him feel that he has sunk into a pauperized substrata.

I think this is a wretched job; wretched in every way. Politics is bad enough in any shape; but it shouldn’t get around to manhandling the destitute.

I could go on and on. It is hard to believe that these conditions exist in a civilized country. I have been going into homes at mealtimes and seeing what they eat. It isn’t possible; it isn’t enough to begin with and then every article of food is calculated to destroy health. But how can they help that; if you’re hungry you eat ‘to fill up—but the kids ain’t getting what’s right for them; they’re pale and thin. I can’t do anything about it and sometimes I just wish we were all dead.’

I’m not thrilled with Massachusetts.

*

Camden, New Jersey

25 April 1935

My Dear Mr Hopkins,

I have spent a week in Camden. It surprises me to find how radically attitudes can change within four or five months. Times were of course lousy, but you had faith in the President and the New Deal and things would surely pick up. This, as I wrote you then, hung on an almost mystic belief in Mr Roosevelt, a combination of wishful thinking and great personal loyalty.

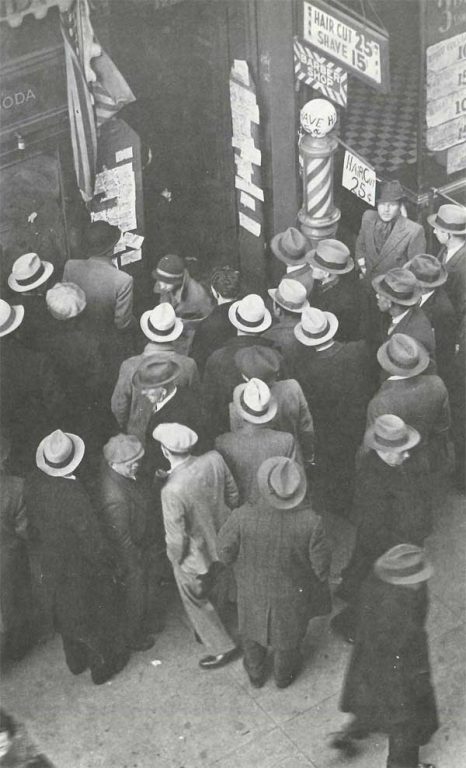

In this town, and I believe it is a typical eastern industrial city, the unemployed are as despairing a crew as I have ever seen. Young men say, ‘We’ll never find work.’ Men over forty say, ‘Even if there was any work we wouldn’t get it; we’re too old.’ They have been on relief too long; this is like the third year of the war when everything peters out into grey resignation. Moreover they are no longer sustained by confidence in the President.

At one big meeting I attended the high point of the evening was a prize drawing: chances were a penny apiece and the prizes were food: a chicken, a duck, four cans of something, and a bushel of potatoes. At the risk of seeming slobbery, I must say it was one of the most forlorn and pitiful things I have ever seen in my life. These people had somehow collected a few pennies. They waited with passionate eagerness while the chances were read out, to see if they were going to be able to take some food home to the family. The man who won the duck said, ‘No, we won’t eat it, my little girl has been asking for a bunny for Easter and maybe she can make a pet of the duck. She hasn’t got anything else to play with.’

I had a revealing talk with the local president of the Union, an American (most of the labour here is Italian, Polish or very illiterate Negro). He is a superior kind of man, intelligent, cynical, calm. He has of course been laid off. He says that the speed with which workers become demoralized is amazing. He expects that his own Union cohorts will stay in the Union for a few months and then drift into unemployed Councils or Leagues. He says also that it’s terrible to see how quickly they let everything slide; it takes about three months for a man to get dirty, to stop caring about how his home looks, to get lazy and demoralized and (he suspects) unable to work.

This matter – the demoralization point – has interested me; I didn’t originally bring it up, but found the unemployed themselves talking about it, either with fear or resignation. For instance: I went to see a man aged twenty-eight. He had been out of steady work for six years. He lived on a houseboat and did odd jobs of salvaging and selling wood and iron. He told me that it took from three to six months for a man to stop going around looking for work. ‘What’s the use, you only wear out your only pair of shoes and then you get so disgusted.’ That phrase, ‘I get so disgusted . . .’ is the one I most frequently hear to describe how they feel. You can understand what it means: it’s a final admission of defeat or failure or both. Then the man began talking about the new works program and he said, ‘How many of them would work if they had the chance? How many of them even could work?’

Sometimes the unemployed themselves say: ‘I don’t know if I could do a real job right away, but I think I’d get used to it.’

The young are as disheartening as any group, more so, really. They are apathetic, sinking into a resigned bitterness. Their schooling, such as it is, is a joke; and they have never had the opportunity to learn a trade. They have no resources within or without; and they are waiting for nothing. They don’t believe in man or God, let alone private industry; the only thing that keeps them from suicide is this amazing loss of vitality: they exist. ‘I generally go to bed around seven at night, because that way you get the day over with quicker.’

Photographs © BBC Hulton Picture Library