A few weeks before the first cases were reported in New York, I went in for my surgery. They had to remove what they referred to as a tumor, but what I’d always known almost affectionately as ‘my bald spot’ – a naked splotch of skin the size of a silver dollar on the upper left quadrant of my skull. It was my ugly birthmark – a quirky hidden trait that only used to bother me after swimming, hair wet and oddly parted, exposing my raw epidermis to the sun, or at the start of a relationship when a man would caress my hair, otherwise voluminous, healthy, and rich with waves while watching a movie, and I’d work to move his hand elsewhere, away from that crude indicator of my imperfection.

But sometime around my thirtieth birthday, I noticed this unseemly little secret becoming more and more obvious. Instead of only being visible on rare and intimate occasions, it had begun to unveil itself at inopportune and unexpected moments for no reason at all. At events and gatherings, acquaintances had started to approach me with a sense of startling familiarity, interrupting a conversation I was having with someone else to ask what that was peeking through my hair. I struggled for hours before going out, attempting to fashion some sort of discreet combover using the underlayers of this small section of my mane before, in capitulation and frustration, throwing on a hat after fucking up the rest of my hair irreparably throughout the course of my efforts. Or, even worse, I’d be alone in bed, scrolling through photos posted after a party at which I’d thought my combover was effective, horrified to realize that someone had caught me in profile, unawares, the sore-like flesh atop my head the only part of me looking directly into the camera, tagged with my name, attaching itself to me in digital foreverhood.

I’m an adult now, I thought to myself. I have control over my body. And, feeling desperate, I paid a visit to the dermatologist to see what could be done, resolving that if the procedure were too laborious or invasive, I’d shelve the prospect of its removal yet again and figure out how to be a person who looked normal in hats, or shave my head entirely to at least make it uniform. Or so I could pretend I suffered from something that might, instead of being merely grotesque, court pity.

I’d visited my dermatologist, it seemed, at the start of every new decade. Like clockwork, my dad would start asking me about it – ‘How’s your head?’ – and once again, I’d be reminded of my pink patch as I entered into some new phase of life.

It always struck me as too inconvenient and time-consuming to remove – balloons would have to be implanted under the skin, stretching my scalp for months until they could snip the afflicted area away. As a child, I wasn’t bothered by it enough to justify undergoing such a lengthy process, and then as a young woman, I was too vain to leave it temporarily undisguised and inevitably put it off and off.

‘Why didn’t you get rid of it when I was a little baby?’ I’d ask my father, longing, as I sometimes do, for infancy, annoyed that this indisposition to my allure could have been negated in a past so distant as to precede any recollection of it, so long ago that it would have never been my problem at all.

But he’d reply, holier than thou, ‘Should I have done so without your consent? Should I have put you through a traumatic experience that you wouldn’t have been able to understand?’ Bullshit. As if that would have been the only time.

There was nothing decorating the white walls at the dermatologist’s office except for a small shelf only big enough to hold a block, a deformed wedge of plastic displaying the various layers of human skin. Epidermis, dermis, subcutaneous and connective tissues, plus all of the other skin appendages (hair, sebaceous glands, sweat glands, and nerve endings) that can be nauseating to think of as part of a human body, but are particularly unsightly when blown up into an isolated model at thirty-five times their normal size.

Bored, waiting for the doctor to join me in the room, I examined it closely. Instead of picking it up and turning it in my hands to study the details the way I would a Rubik’s Cube, I repositioned my own body around it, taking little steps to each side and leaning in seriously, as if I were at a museum, a gallery with barer walls than these. The follicles resembled tree pits, and five hairs stood straight up from them like electrocuted elms, the blood vessels below severed roots. The block reminded me of the Meat-Shaped Stone, a piece of art I’ve only seen on the internet, which I’ve also never held in my hands, or only through the phone in my hands, pinching the page to enlarge the details: the incredibly convincing pocks on the topmost layer the follicles on a pig’s hide, stained the color of soy sauce; the curvy folds of rock-hard fat; the marbled layers of succulent jasper; the gold plate it sits on like a capsized crown. One could be convinced to take a bite, only to find themselves holding their face, aghast, having chipped a tooth.

Cotton swabs and Q-tips neatly filled two jars to their very tops – the physician’s assistant must have been taking the task of refilling the jars every morning very seriously – alongside bottles of sanitizer and hydrogen peroxide. Next to those, settled within a clear vase, the elegant flowers and foliage of a two-foot orchid loped over the aluminum case dispensing nitrile gloves, which prevented the dermatologist from ever having to actually make contact with any of his patients’ skin.

Our visit was brief, and this time, he didn’t coddle me. My spot wasn’t cute anymore. It wasn’t a ‘strawberry patch’. It was a disgusting and seemingly expanding flaw I could get rid of, and it was even more disgusting to be so lazy or nervous as to do nothing. He didn’t say this, of course, but appeared satisfied as he insisted that it looked cancerous and should be biopsied and removed as soon as possible. I stood to walk out of the office, perversely excited about this no-way-out circumstance. It was only then, upon touching one of the orchid’s petals between my fingers, that I realized it was artificial, purely decorative. Of course, it had to be – there were no windows in the room.

‘Finally,’ I said, already halfway through the door. ‘Let’s get it over with.’

TOTAL CONFIRMED GLOBAL CASES: 3,068

I was connected to a semi-famous plastic surgeon at the tip of the city – uptown, ‘where the best hospitals in the world are,’ my husband told me with pride, a little overly enthusiastic.

To my surprise and relief, Dr. Taub said no balloon would be necessary. They would instead cut other areas of my scalp around the tumor and along my head to make up for the scalp’s lack of elasticity so as to be able to remove it in one go. He and his team would stretch the torn skin and stitch my scalp back together again.

‘Like Frankenstein,’ I joked, and booked an appointment for the following week.

TOTAL CONFIRMED GLOBAL CASES: 3,314

In the hospital waiting room, I signed paper after paper, none of which I read. Glancing up between pages, I studied the signs. telephone for emergency use only. no smoking. no open flame. no exit. please do not leave women unattended.

I did a double-take. please do not leave children unattended.

They handed me a gown to change into and those horrible blue socks, which sagged unfortunately at my ankles as I shuffled to the OR. I passed spaced out, drooling women on stretchers, who struck me as only half there. It wasn’t clear to me if their lobotomized states were what they were being treated for or with. But I knew I’d look like that too. Maybe later, maybe next year, one day.

‘We’re going to take good care of you,’ the young man said as he assisted me onto the operating table, looking at me sensitively with eyes bluer than my own. He was hot. Not handsome but model hot, and if the circumstances were different, I would have said something flirtatious and charming, asked him questions, but instead I bit into my tongue. I felt like a little girl in slippers, an old lady in an unflattering nightdress, too embarrassed to speak.

A slightly shorter, only marginally less attractive brunette pricked my veins with needles and connected me to a herd of grunting machines. He warned, ‘We’re giving you some relaxing medication now.’

‘Oh . . .’ I replied as the ceiling undulated in newly formed waves. I smiled and tried to hold it for a little longer. The lights on the ceiling were becoming less abrasive, and I felt less like I was on a UFO under the penetrating examination of an alien cohort and more like I was the glowing centerpiece of a Dan Flavin installation. I was a rock fluorescing under their touch, I was the earth itself, and I could feel but not feel them chipping into my crust, sending seismic vibrations down through each layer, all the way into the center, hot and dense as the sun. And then I was reversing, melting, and moving back up through the surface. A volcano was erupting, a rocket was gaining speed, exiting through the troposphere, stratosphere, mesosphere, thermosphere before popping through it like a pimple, debris finally released from deep within an infected pore, into the exosphere, and then I was gone.

TOTAL CONFIRMED GLOBAL CASES: 4,145

When I woke up, my breasts were semi-exposed by my gown. The nurses assisted me, one on each side, into a wheelchair, and I, for the first time in my life, affected modesty and adjusted my frock with great effort to make sure my nipples weren’t even partially visible. They rolled me into another area of the hospital, where yet another nurse took my arm and sat me in yet another seat, big and brown, stained and cushioned. It seemed to be swallowing me up. He connected me to some monitors and tossed a blanket over my lap. I knew my mouth hung open, slack. I was the women I’d seen earlier. ‘It hurts,’ I muttered. It didn’t really hurt yet, I was still enjoying the doped-up feeling from the anesthesia, but I knew it would soon.

The nurse looked into my eyes. ‘What did you say, sweetheart?’

‘It hurts,’ I slurred again.

‘Do you want some Tylenol?’ I didn’t respond, and he paused only briefly before offering – ‘Oxycontin?’

TOTAL CONFIRMED GLOBAL CASES: 4,366

Eventually, I woke again, now with my husband in a chair near my side. He kissed my cheek, and I insisted on leaving. I desperately wanted to wash my hands. How filthy I felt in a place so sterile.

Soon enough, they unhooked me, and I was able to stand and walk downstairs and crawl into the passenger seat. He asked me how I felt, and I felt nothing at all other than, perhaps, a mild irritation I couldn’t find a justification for or the words with which to express it. If I had to compare it to something, it was most akin to that feeling you get after being out all night, having the time of your life, and then all of a sudden, a deep urgency to get home bubbles up in your chest like trapped air, and you need to leave that second, you can’t wait any longer, you peace out without saying goodbye, the journey to your bed impossibly far. Or when you take a day trip to somewhere outside the city, and you’re looking at the woods passing monotonously through your window and you can’t stand to be in the car, you feel imprisoned in your seat, every moment a moment wasted, though you’re not sure what you would have preferred to be doing instead.

At home, I fell asleep for six hours, woke up, had a sip of apple juice, fell asleep for another six. Then eight, nine, ten, and so on. Days passed.

TOTAL CONFIRMED GLOBAL CASES: 5,634

By the time I emerged from my semi-coma, thousands had already been affected across the West Coast, Asia, Europe, and Canada, but it hadn’t really reached NYC yet, or at least no one was acknowledging it. I had missed the first big wave of cases to hit the South, deep in slumber, experiencing a series of near-nightly dreams that always began with the same scene of me digging, nervous habit, for something in my own body. If no one was watching, I’d then bring my finger to my nose. In the dream, the smell of my finger smudged with fungus conjured memories of baking with my grandmother in her kitchen, watching the yeast wake, activate, go from something dead to living, something nothing to breathing. The wet center of the undercooked banana bread I could never seem to get quite right, no matter to what degree I adjusted the temperature, the baking time, the size of the pan. But the scent also pushed me down into her basement. Forgotten, moldy, unfinished. In the dream I’d place my finger into my belly button, then scrape out flakes of skin from under my nails, and it was satisfying the way cleaning one’s ears is satisfying, or tweezing one’s eyebrows into a perfect arch, trimming one’s nails. Removing all the excess bits. Getting down to the bare minimum, the thinnest layer of oneself.

I’d never had a dream that was so clearly progressive before, picking up where the last one left off. I have a few places I regularly visit in my dreams, but what happens there each time is never the same, the events exist independently of one another, the locations are familiar, and maybe similar things happen, but there isn’t a developing storyline, the narrative isn’t a continuous thread across nights and weeks. But in each dream, the hole in my stomach grew larger because no matter how often I touched it, there was always some gunk to scrape off, an edge to even out. I’d entertained the compulsion so thoroughly and mindlessly, so naturally, in other words, that when I’d wake up with a throbbing head for those few minutes between each period of sleep in the quiet solitude of my room, I’d sit on the edge of my bed and hunch over myself, the lamplight from the side table shining yellow on my skin but hardly offering a view into the hollow at the center of my abdomen. It was so realistic, I needed to make sure the wound that dream-me was maturing, growing, tending to like a garden, wasn’t becoming a pit I might actually fall down. I had never realized how deep my belly button was before; it was unnerving. And the funny part about it all was that I realized I did seem to have a tiny little hole in the deep heart of it, a cut – as if my umbilical cord hadn’t ever properly healed. But nothing was leaking or would leak out, and in the end, everything was more or less as it should have been and as it always was.

There was another dream in which I found myself in my grandmother’s room and, picking up from the dresser a small picture frame playing a video, I watched myself sucking the dick of a man whose face was cut off by the frame. Watching the video, I was struck by the hunch in my back – I looked like a snake tangled in a circle of itself, swallowing its tail, or an old lady. Atop the comforter, I noticed a strand of hair, recognizable as my own, not my grandmother’s, because it was red, for now, as opposed to gray. The strand of hair reminded me of a necklace from yet another dream, which had also been strewn on my grandparents’ bed as carelessly as a strand of hair. I could hear the shower running – my grandmother was cleansing herself in the room over. I turned the frame face down on the dresser.

My dreams that week were so vivid that sleeping didn’t feel restful; they were as active as daily life. And in the interim between each session of my sleep, looking out at the damp street through my window, the way the falling drizzle might have mingled with the shadows on the wet concrete or the way the steam emanated and hissed off the heater like an apparition, or the way I could see green and purple inside the flames in the fireplace instead of just orange and red as before, it all felt like a movie I lived inside. A certain innate distance became accessible to me in a way I had never experienced. Life was a picture frame on a desk I picked up sometimes, cocking my head to the side as I tried to recognize myself in all my strange postures.

I’d wake up between cycles with an aching in my neck worse than anything I’d ever felt before. Not only was my neck deeply sore, but behind my eyes was, too, and both my neck and eyes would occasionally twitch involuntarily. I knew it was from the way they contorted my body during the surgery, and it hurt to think of them twisting my head as if I were an inanimate object, a doll whose skull could be turned all the way around on its body, so they could get the necessary angle. I shuddered to think of how far beyond or deep inside myself I must have been to not even protest.

TOTAL CONFIRMED GLOBAL CASES: 7,385

The scope of the syndrome and the rumors circulating all around were still kind of difficult to believe, but we knew it was creeping closer and closer to the city every day. The news was cryptic and unsure of itself, and I, like so many of the women I knew, found everything to be blatantly unbelievable. The bars were packed, and the air tripped over itself with excitement. It was the first teasing days of spring, the scent in the air a cross between death and cum. I was almost horny again, though still insecure because of my unhealed wound and the mess the surgery had made of my hair, which distressingly had begun to fall out in clumps.

It didn’t make sense – why would I be losing hair? Why did my spot only seem to be growing when that was precisely what the surgery was intended to correct? I tried contacting my doctor, but his office had stopped answering calls and wasn’t responding to my emails. It had been so easy to book the initial appointment and procedure, but it seemed likely that hospitals were beginning to feel the effects of the city’s panic. I told myself to be patient. I Googled things. I concluded that it was shock loss, an affliction that apparently most often befalls a small percentage of men after they resort to hair transplants in a despairing attempt to combat baldness. This didn’t make me feel particularly attractive, but it was comforting to know what I was experiencing was a somewhat normal event following trauma to the scalp. Injuries heal, hair grows back. It made no difference anyway. The news said the syndrome wasn’t contagious, but I wouldn’t risk possible infection by going to the hospital any time soon unless it were absolutely necessary.

TOTAL CONFIRMED GLOBAL CASES: 10,885

I met up with a couple of friends for happy hour at a bar with open windows. The buzz of the syndrome was all around us, and it wasn’t clear what tomorrow or next week would hold. But for the moment, we had martinis, gossip, and the terrible thrill of knowing we were on the cusp of something of historical magnitude, something none of us could grasp yet soon enough would be unable to forget. The only anesthetic for whatever global ordeal we were about to confront would be the passing of much time – decades probably, the length of our lives – or death itself, or drugs. We called our guy. I put my hand to my head and fixed my hat, felt for the fabric underneath covering my stitches. Because of the surgery, I’d been off booze for a few weeks. The vodka warmed my throat while the cool air grazed the back of my neck, a perfect alchemy.

TOTAL CONFIRMED GLOBAL CASES: 11,109

When we got to Mira’s we huddled around her glass table, broke out lines, and passed a twenty-dollar bill between the three of us while Jess pulled up videos on YouTube. Making fun of our apocalyptic moods, we watched a series in which a pair of two hairy hands unwrapped and displayed Meals, Ready-to-Eat, preparing and reviewing the contents of the army rations as if they were hosting a show on the Food Network. We traded conspiracy theories about the syndrome and joked about cocaine’s antidotal potential. We tried not to get too paranoid and switched to watching videos about primitive technologies, in which two men worked in silence to find groundwater, build furnaces and boats, catch fish, and construct habitats in some place that seemed impossibly far from us. ‘Do you think . . .’ Jess started to speak but was interrupted by Mira’s phone. Mira looked at us with lowered eyebrows and mouthed ‘Virginia,’ even though there was no one but us to hide her voice from in the room. Jess and I squinted in surprise and incredulity as she picked up and put Virginia on speaker.

‘Heyyy,’ the three of us said.

Then Mira, on behalf of the group, asked, ‘How are you? What are you doing? Come over?’ Her invitation betrayed only the slightest hint of confusion in its undertone.

Virginia had been immersed in the honeymoon phase of her not-quite-one-year-old relationship. For the first couple of months we remained unfazed and unoffended by the rarity of her appearances at gatherings, the bar, dinners, etcetera. But when eight months had passed and she still hadn’t reemerged, and only seemed to be slipping further and further away into an enviable haze of love, after missing birthdays and openings, solo performances and weekend excursions, we mournfully began to acknowledge that her reprieve from the friend group might be permanent. Nevertheless, Mira weathered the evasions and continued to text her whenever we were together.’ We need to keep the door open,’ she reminded me one evening a few months back, when the gin and tonics were making me particularly acrimonious.’ Don’t you remember when you went through this phase?’ I didn’t, but I shut up. ‘Aren’t you glad we were here to receive you when you woke up from your stupor?’

Virginia’s voice was small on the other side. ‘I can’t.

I’m sick. I’ve been sick for like a week.’

‘Oh no, with what? How are you feeling?’ Mira asked, straining a bit in her attempt to sound casual.

‘I definitely have the thing . . .’ Virginia told us. ‘I’m nauseous, my head feels super heavy, and I can’t remember . . .’ She trailed off.

We heard some rustling on the other end of the line as Virginia adjusted her position. ‘Are you in bed?’

‘Mmm,’ she replied distantly, disinterestedly, and I tried to suppress the annoyance I could feel spreading visibly across my face. She was the one who called us. We heard the metal chain of the necklace her boyfriend had bought for her a few months prior clink against the glass of the phone’s screen as she shifted. He was the type to surprise her with gifts midweek, no reason or special occasion, just because. He loved to spoil her, and she loved that about him, his generosity, his thoughtfulness. That’s what she told us, anyway. And I could see how smart he was to realize how easy it was to be exceptional; all he had to do was keep his wallet open, her vase full of flowers.

Virginia was saying something, but it was muffled under her bodily movements. I could imagine her long, delicate fingers wandering like spiders over the nameplate resting on her breastbone, dancing around the curving letters of her pet name.

g i n n y.

‘V? You’re like, laying on your phone, we can hardly hear you.’

‘I’m so nauseous . . .’ she repeated, now breathing heavily, without seeming to realize she’d been in the middle of a sentence. She paused again before finally adding, ‘I’ve been having really really bad nightmares too, but all I can do is sleep. I thought I had a cold earlier in the week, but it got really bad yesterday. Honestly, I’m kind of . . . I’m kind of scared.’

Jess and I looked at each other again, lowering our eyebrows, communicating telepathically.

‘What are your nightmares about?’ I asked, but Mira gave me a glowering look.

Regretful about my last question, I asked another without giving her time to answer, an attempt to erase what came before. ‘Where’s Greg?’

An anesthesiologist at New York-Presbyterian, I figured maybe he’d know something we didn’t, or at least be able to put her in touch with a physician who did.

‘He’s been working a ton of overtime. I don’t know. I don’t know. He says it’s all in my head.’

‘I’m sure you’re fine,’ Mira said.

‘Maybe it’s allergies,’ Jess said unpersuasively. Then, trying to be considerate, she added, ‘Do you want us to bring you some soup?’

Back when we were all single and hungover, our Sunday tradition was brunch at an old diner in the East Village where waitresses with cat fur on their pants and smoker’s coughs filled and refilled our coffees as we rehashed the details of the previous night.

‘Yeah,’ Mira said, ‘we could bring you matzo balls from our spot.’ We waited for an answer, but none came. Mira looked at her phone, the call’s timer still running, the line still connected. ‘Hello?’

We couldn’t hear Virginia’s breath anymore, but we could hear doors or cabinets begin to open and close and then, in the distance, a faucet running.

‘V? Are you still there?’

TOTAL CONFIRMED GLOBAL CASES: 11,320

Back home, I wasn’t feeling so great either. Sweating, I got in the shower, where the water from our luxury showerhead promised to cascade over me like rain but instead fell out in weak driblets. It was ironic, spending extra money for the mimicry of something that flowed outside in abundance and which, inside, didn’t make me feel any wealthier but rather cold, lost, and poor. The embarrassing water pressure filled me with a sense of lack and looking at the mold and grime growing slimy in the grout, I was overwhelmed with the pressure of obligation, reminded of every annoying little thing I was expected to do but so rarely did. Tomorrow . . .

I opened my mouth and let the warm water pool in the back of my burning throat. I told myself to stay calm. It could be psychosomatic, it’s probably just the cocaine, why were we so stupid? Why were we still out? What the fuck was going on? I lathered shampoo between my palms and began to wash my scabbed scalp. Compulsively, anxiously, I scrubbed at my wound too vigorously and felt the silken sutures begin to loosen. Despite the pain, I started to pull them out, unpeel the skin. I couldn’t stop. I went deeper. When I finally took my hand away there was a piece of plastic between my fingers, a mere drop of blood clinging to it like an ornament. The material reminded me somehow of a feather, or a small bird’s hollow bone, so delicate despite its artificiality. Holding the plastic up to the bathroom light, it became translucent. I brought it closer to my face, squinting as if looking directly into the sun. Through it, I could see two nearly microscopic strings of digits intersecting in the middle, spiraling into the shape of a double helix, a twisted ladder. And that was when I knew.

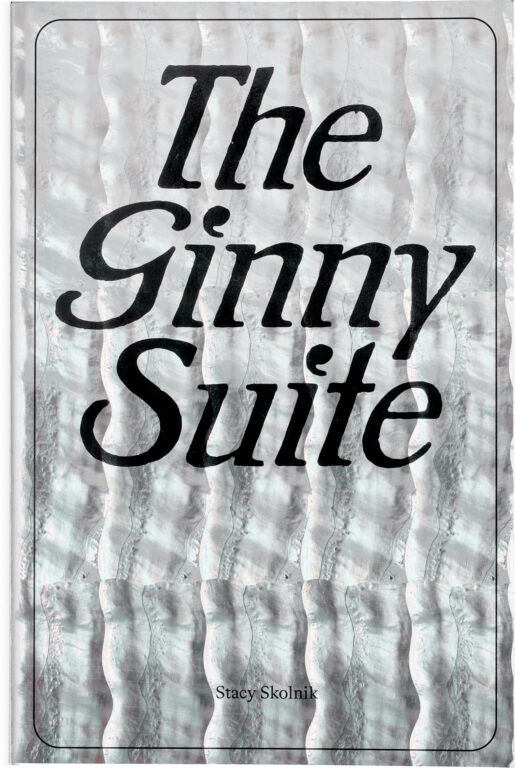

Image © Umberto Salvagnin