Today Madame’s stool was shaped just like a petit-croissant. Bébé flushed it down, watching the pastry-like shape come apart with the force of toilet water. She was fascinated by the different breads available in Paris. Bread for her meant something very different from rice, and Bébé made an effort to practice their pronunciations so she would not make a fool of herself at the bakery: baguettes, boules, croissants, fougasses.

For her bathroom needs, Madame insisted on a two-quart casserole dish and a hand painted Limoges pitcher. Bébé scrubbed them out with pine-fresh cleaning liquid. This she’d bought for Madame with her own money. The old cleaning liquid smelled like a hospital ward, not a home. When Bébé brought the pitcher and dish back into the room and stowed them under the bed, she turned the handles outwards for Madame’s easy access. Madame did not even seem to notice she was back with the emptied receptacles. She was busy reading the papers with a magnifying glass, stabbing at a picture of the newly unearthed remains of an Egyptian mummy. Be careful of archaeologists, Madame warned her without looking up, they are the worst. Them, murderous surgeons, and tabloid photographers! Why should a queen of the Nile be woken from her slumber, just because a few thousand years later some riffraff wants to have a poke at her face under all those bandages?

Bébé listened as she discarded last week’s lilies.

Replacing them with sprightly ones and refilling the water, she shook the blooms lightly so they would spread themselves out in the vase. She did not always know what Madame was talking about, but Bébé liked that Madame talked to her anyway. Did Madame talk aloud to herself this way when she was alone, or did Madame only do it in her company on Sunday? The oven dinged and she stepped out to retrieve the cotton towels and flannel bath blankets. She’d popped them in to warm them up on low heat. Draping them on her forearms, she approached Madame’s bedside with a basin of warm water. Madame went en garde as soon as she noticed the offending objects, pushing aside the newspapers as she wielded a tassled decanter. Fool, she called out, bathing is for people like you! People like me have perfume.

Madame spritzed the air aggressively with her bottle.

Bébé waited for the fragrant mist to settle before approaching the bed. Before she grew accustomed to Madame’s ways, she’d walked headfirst into the cloud of perfume. It stung her eyes terribly, and as she flushed them out with water, Madame could not stop laughing: Blinded by Yves Saint Laurent, serves you right! Do you know he said he would make me a perfume?

Now Bébé knew better.

Having put up her fight in principle, Madame would surrender peaceably in practice. If you started at her shoulders and worked downwards Madame would screech, but if you massaged her feet through the bath blanket, folding the bed linen back bit by bit, she would let you get through with it. Bébé slicked some moisturizing cream onto Madame’s papery skin. Although she was bedridden, Madame had no bedsores. Only itchy skin, soothed by the seasonal aloe Bébé procured from the Turkish supermarket near her guest workers’ dormitory. After moisturizing, Bébé trimmed Madame’s fingernails and toenails, and finally, she bicycled Madame’s legs forward and backward to exercise them. If Madame appeared to be in a fairly good mood, Bébé would encourage her to get up and walk across the room. Her flesh was atrophying from the bone with lack of use.

Try, Bébé said. Bed to TV.

Why should I try?

Bed to TV. Bébé hold Madame.

Stop skiving on the edge of my bed, the old woman said. Don’t come so close to me. Have you washed your hands? You’d best get on with the housework before I lodge a complaint with that uppity-tuppity lawyer lady.

*

Bébé’s Monday-through-Friday cleaning job, in one of the administrative buildings of the city’s tax department, had been arranged for by a pro bono human-rights lawyer. The lawyer’s father was an old bird in the cabinet, a minister’s aide. It wasn’t difficult to pull some strings on a topical problem, sold smoothly as a pilot program her fledgling organization was looking to implement with selected female refugees: Bébé, two Tunisian sisters, an Iranian, a Vietnamese child. A private donor had given a substantial sum through the UN, and a bite-sized trial would help them build up a prototype for meaningful refugee integration, skill training and job matching in the future on a much wider scale.

Bébé had asked the pro bono human-rights lawyer if she could take on an extra weekend job since there was nothing to do on weekends.

You should take yourself out, the lawyer said.

Nowhere to go, Bébé said.

It’s Paris, the lawyer said encouragingly, there’s lots to do.

For you everywhere, Bébé said, for me –

She shrugged and smiled.

Sensing her class-insensitive faux pas the lawyer stammered: The parks, they are free!

Social enterprise was new to the lawyer. It was deeply invigorating every time she was asked what she did now, and she got to say ‘nonprofit’, ‘female refugees’ and ‘at risk’ in the same sentence. Having quit her high-flying corporate finance job in mergers and acquisitions, she was raring to go humanitarian and vegetarian at the same time to stave off an incipient menopausal midlife crisis. Founding Secondes Chances pour le Deuxième Sexe (SCDS) was more challenging than she’d anticipated. She was impatient to roll out her plans for PTSD counseling and art therapy, but of course the basic logistics like gainful employment and shared housing had to be put in place first. Her father advised her to cut it down to Secondes Chances when she was registering the charity, but the lawyer was unwilling to lose the Beauvoir reference.

Second Chances for The Second Sex, Papan. I thought you would get it right away.

I did, her father said dryly. Over dinner he told her about how the Ministry of Culture supported Legion of Honor awardees who had fallen into various states of disrepair, like Malraux. The lawyer rolled her eyes. Men, she said. Her father wagged a finger. Not so fast, he said, Piaf before she passed, how do you think she maintained the Riviera villa? And Dietrich now, too.

She’s French now, the lawyer said, is she?

Does it matter, when you are Marlene Dietrich? All the old fogies in the cabinet are still dying to drop their trousers for her. She even wrote a postcard addressed to Mitterand directly, asking if he could send her the new cordless telephone she had seen advertised on the TV – and a maid. I miss the General very much, she wrote, he was a personification of my code of conduct. A great man. You know we have de Gaulle’s portrait in the office. Mitterand looked up at it, and told me I’d best look into Miss Dietrich’s needs. What am I now, a personal shopper for some ancient who still knows how to milk what’s left?

An invaluable skill for any woman, the lawyer joked. Actually, she said in a serious tone now, why not use one of my refugees? They’re being trained as seamstresses, cleaners, janitors. There’ll be a fair remuneration, yes?

But my dear, can they be trusted?

Papan!

Oh, I didn’t mean it that way!

*

Bébé had been briefed by the lawyer – the woman she would be working for on Sundays was about ninety years old, and she was once a very famous actress. She was to be treated with utmost discretion and addressed as Madame at all times.

Bébé did not know who Madame was, but dusting the cabinets and shelves and looking at all the pictures, she saw that Madame was the center of the picture even when she wasn’t in the center of the picture.

The old woman had a sweet tooth.

She was always asking for dessert and pastries, and Bébé was by now familiar with the short walk from avenue Montaigne to various pâtisseries in the huitième. Bébé kept receipts for everything, although Madame considered herself above such things. Spare me the trouble, she would say, keep the damned change! What am I going to do with a pocketful of coins, go to the arcade? Once Madame had craved gelato, and Bébé, afraid it would melt, sprinted back from the ice-cream parlor an avenue away, cone in hand, tripping and twisting her ankle on a curb. Disguising her limp when she reentered the apartment, she handed the cone to Madame, who licked it and declared unhappily: This is banane. I said vanille!

It was macarons Madame wanted today.

When Madame wanted macarons, she wanted only Ladurée macarons from rue Royale, but Bébé could pick the flavors. A trip to Ladurée was a treat. The display, which changed regularly, could be counted on to mesmerize: lilac meringue, caramelized puff pastry, Morello cherries, rose petals. Looking into the shop window Bébé felt like the sort of girl for whom the world was precious and everything was possible. Back home in Taishan she encountered a cake just once. White cream frosted over sponge with white icing, it was ensconced in an icebox and transported from the city to her village for someone’s wedding, where it stood out amid steamed chicken and roasted pig, both fowl and beast with heads still on, eyes hollowed out.

Bébé snuck into the compound, watched as bride and groom bowed to sky and soil. Some adults disapproved of the white cake. Untraditional, funereal, inauspicious! Freely they dispensed negative comments, though that did not stop them from clamoring for a piece or two when the cake was cut. Bébé received a slice. How the cream tasted: like it was from a better, faraway place. She let it melt slowly on her tongue. On her next birthday, as she sat with her parents over the longevity flour noodles her mother had prepared, the same as she did every year, Bébé said: I would so like a cake next year.

She received from her father a little slap.

Though it did not hurt, she flinched as soon as she recognized the condescension in its lightness. She sat outside the house in disgrace. Her mother came to her. Without asking, she began combing and braiding Bébé’s hair, affixing a big red ribbon to the end of her plaits. For luck, her mother said tenderly, make a wish.

I wish I were someplace else, Bébé said.

Taken aback, her mother looked at her vacantly.

With an uncertain smile her mother wanted to know: Where?

Bébé ran to the creek on the edge of the village. Upon catching her murky reflection, she pulled off the hair ribbon and threw it into the water. Then she was afraid it would be spotted by her mother, so she squatted to retrieve it with a broken branch. Digging a hole with her hands, she buried the ribbon. As she washed the mud off, she pressed her palms together and whispered: Better off dead than to remain here. With the end of a twig she traced the characters in the sand:给我留在这 我死了算了. Before she left she dribbled river water over them, so nobody but the earth could know.

Now standing in line at Ladurée, sunlight streaming through tall windows under the champagne glow of crystal chandeliers, pointing out rose, lychee, and pistachio bonbons to fill a celadon-green gift box finished with a powder-pink ribbon, nodding while saying to the shopgirl, Une boîte de douze: it all made her feel so – fine. You could let yourself go in an ugly little town. A beautiful place made silent demands on your person in no uncertain terms, even as it gave nothing of itself back to you. What Bébé was enthralled by wasn’t Paris. It was only the person she liked to think she could have been here.

*

Numerologically, 1988 had been an outstanding year for Bébé to undertake a new venture in a foreign land. It was imperative to set out before the year was over. She was eighteen in a double-prosperity year, eighty-eight, falling under the sign of the dragon, and she had been guaranteed a job in a Nike factory in Marseilles.

For the job matching, Bébé paid a hefty brokerage commission to a subsidiary agent of the Corsican-Chinese Friendship & Trade Association in Shanghai. She’d been out of the village for three years, saving up the scant wage she made in one of the city’s new textile export factories.

When she wrote her mother in Taishan to say she was leaving Shanghai for Paris, her mother asked where that was. Bébé enclosed in her reply a world map most rudimentary, hewn from hearsay and her imagination. Her mother wrote back: Shanghai is far enough. Her mother wrote back: Explain to your long-suffering parents. What is the difference between working at a factory in China and a factory in France? Her mother wrote back: Why does our daughter have a comet for a heart? The restrained and impersonal calligraphy of her mother’s letters belonged to the village scribe (three yuan a page), who also read to her the letters she received in a reedy tenor (free of charge). How embarrassing for her mother to have dictated to the man, likely wringing her thick knuckles on those scraps of fabric she had the gall to call handkerchiefs: 为何咱家的女儿有颗流浪的心?

Alongside three other girls from Shanghai, in the cargo hold of a ship, Bébé subsisted for two weeks on a stash of flour buns filled with preserved vegetables, and tangerine peel to stave off the seasickness. It was so hot and stuffy one of the girls fainted. They stripped her down to her underwear to cool her body, not realizing the floor had traces of ship diesel, leaving her with faint chemical burns on the backs of her calves when she woke. Upon docking, Bébé thought they’d reached Marseilles, but a tall African man appeared below deck and told them, in perfect Mandarin, that they were in Nairobi. Knocked out by his language skills, the girls dissolved into nervous giggles. They had to switch ships to avoid detection, he explained. The transit could take two hours, two days, or two weeks, depending. Depending on what, they asked. Your fortune, he said, as he brought them their first hot meal in a long time, a simple but delicious cornmeal paste with green peas. When he stretched over to refill their drinking water he smiled kindly. The salty-sour edge of his perspiration reminded Bébé of five-spice powder, and she wanted to touch the kinks in his hair.

All Bébé saw of Nairobi was a crane moving a container.

They were given clearance to depart in a few hours.

Safe travels and smooth winds, the tall man said, as he chirruped like a starling and locked the hatch.

*

As soon as they reached Marseilles, the girls were transferred from a container in a shipyard to the back of a van with tinted windows. Welcome to the Corsican-Chinese Friendship & Trade Association, a middle-aged Chinese woman said in Cantonese-inflected Mandarin. She had a bad perm and was flanked by two stocky white men who had collected their passports upon arrival. I am gravely sorry to inform you that the Nike factory has been shut down, the woman continued. Fortunately we have for you options. There was a management fee for the business contacts, transactional logistics, round-the-clock protection, communal housing, but not to worry, automatic installments would allow for ongoing repayment. Things don’t always go according to plan, it’s hard to be on one’s own in a foreign land. Ahyi understands – she referred to herself in the familiar form – Ahyi’s been through it all.

The girl with the chemical burns asked: What business contacts?

Don’t be stupid, another girl said, already crying. She’s talking about prostitution!

What an uncivilized word, Ahyi said. We much prefer to call our girls imported goods.

We could report you to the police, the girl with the chemical burns said. She was beginning to hyperventilate. You’re illegal immigrants now, Ahyi said serenely as she held a plastic bag over the wheezing girl’s nose and mouth. Breathe, she instructed. To the rest of them she said: I can assure you life with us will be more worthwhile than life in jail.

When the van came to a stop and the side door slid open, Bébé dove out of it, vaulting directly into the thickset arms of an older white man they would come to know only know as the Corsican. He pulled Bébé toward him by her hair. Pity to scalp such a pretty face, Ahyi shrugged, but it’s no problem to put a wig on you. As she stepped around to the back of the van, she pushed her quilted floral jacket back to reveal a holstered handgun. Please, Ahyi said, for your own sake, don’t do something like that again. What do you take us for, amateurs?

The Corsican-Chinese Friendship & Trade Association was cordially established when Ahyi and the Corsican were wed almost a decade ago, having merged their hearts to consecrate their criminal potential. Ahyi’s homespun syndicate ran a job agency in Shanghai that was a front for human trafficking, specializing in a Shanghai-Nairobi-Marseilles route and a Nanjing-Belize-Los Angeles route. The Corsican’s crew ran a prostitution ring. Under the Corsican’s aegis an assortment of third-world women – Bulgarian, Turkish, Russian, Chinese, Kazakh – catered to businessmen passing through Marseilles.

Mostly the clientele was French and Corsican, occasionally Spanish and Italian. Nationality regardless, they were curiously the self-same species of man: middling, middle-aged, and married, potbellied or pinched in polyester suits they filled out too much or too little. The transactional logistics took place in little motels around the edge of the city center furnished with fusty beds that felt used even when they were freshly made, to and from which the girls were heavily escorted. Ahyi, who spoke a fluent if sharply nasal French with a strong Nanjing twang that made it sound more Cantonese than French, gave all of them new names.

Fresh beginnings, Ahyi said. Bébé found hers a letdown in this regard.

In French the vowels rose and in Mandarin they descended, but ‘Bébé’ was to all intents and purposes a phonetic facsimile of ‘蓓蓓’. For weeks she was repulsed that all things considered, there was room yet in her for so dainty a variety of disappointment. Even so, Ahyi hadn’t explained to her that Bébé wasn’t really a French girl’s name the way Estelle or Margaux was. One hot day months and months later in Paris, when Bébé learned in the course of the volunteer-run beginner French lessons at the immigrant activity center that her name was the French equivalent of baby, as in infant, as in a term of romantic endearment, as in 宝贝, she put her hand up to go to the bathroom. How do we ask politely to use the bathroom, the teacher cooed, if you please? Bébé kept her eyes on the daisy charms of the teacher’s spectacle chain as she recited, pronouncing the puis-je and the de bain too emphatically: May I please go to the bathroom?

In the bathroom Bébé thought she would throw up, but there was nothing inside. She ran the tap on high, washing her face with brisk, exaggerated motions. Smoothing back her damp hair in the mirror, she gargled her mouth.

Pas de baisers, Monsieur, j’ai dit pas de baisers!

*

Was it a month or a year into her stay with the Corsican-Chinese Friendship & Trade Association that Bébé asked for a diary? She was given a half-used spiral notebook with blue lines. It had a laminated lenticular photograph of a sleeping tiger on its cover. Viewed askance, the tiger opened its eyes and jaws. The thin pages she filled with nothing but tally marks. For all the time that had gone by undocumented in Marseilles, Bébé rounded it up or down to a perfunctory fifty. Her fifty-first client, on a midsummer’s afternoon, was Chinese. That was a first. Other than that, he was reliably that median of man: middle-aged, potbellied, polyester-suited. He stepped into the room, kicked off his shoes, and declared in Northern-accented Mandarin: Best blow my load before shit hits the fan!

Won’t you have a shower first? Bébé said.

Chop-chop, the client said as he stepped out of his trousers. He removed everything but his beige socks, sour smelling in the windowless room, as he squatted on his haunches, fishing a cigarette out of a rumpled pack. He tried to light it, but his hands were shaking. Bébé took the lighter from him and curled her palm around the flame. Surprised by her gesture, he leaned in to catch the fire all the same. Upon finishing the cigarette, he grunted and went to take a quick shower.

When he came he gave a long and strangled shout.

The octave of his cry made Bébé think he was in fact not Northern, but Fujianese. With great solemnity he told her that her 口交 technique was 顶尖. Completely against her will she burst out laughing. He lit another cigarette and offered her one. It was unusual for clients to remain in the room unless they wanted to try to go at it again, for which there were certainly additional charges. As a courtesy, Bébé informed him that her fee was tabulated by time, not activity.

That’s fine, he said, waving a hand. Whereabouts on the old road are you from?

Shanghai, she said, although the answer should have been Taishan.

Ah, he said. A good city.

Yourself?

Fujian, he said. Quanzhou, to be precise.

Biting back a savage smile, Bébé accepted the cigarette. Before she lit up, she asked if it would be all right for her to put her clothes back on. Yes, he said defensively, of course. He remained unclothed as she dressed, but after a moment, saw fit to throw the scratchy blanket over his lower body. No offense, he shrugged, looking down at his loose paunch and the will-o’-the-wisps of salt-and-pepper engirding his nipples, as if noticing them for the first time.

Fully dressed, she turned and brought the cigarette to her lips.

With a steadier hand now he lit her up. He told her he was a small-press publisher and that he had just got off the last plane out of Beijing. The other small-press publishers were small because they had specific aesthetic interests. They were too niche. That, or they were politically inclined, and needed to operate on the fly. He was small because he was essentially interested in publishing translations of European literature.

He was doing nicely enough.

The educated class was hungry for foreign culture after all those years of pastoral proselytism, he said. Let a hundred flowers kiss my ass! Things were stable. Deng Xiaoping is a clincher, my kind of man. An all-out capitalist, mark my words, you’ll see, if he holds on to the hot seat China will be the most consumerist country in thirty, nah, twenty years. It was a good time for business. Place your bets. Balzac flew off the shelves. Not so much Chekhov or Tolstoy. Nobody bought Proust, ha-ha. Zola did pretty well, for some reason.

Some were reputable reprints of translations that had gone out of print. Others I hired the best translators I could. I paid them better than most. So I was breaking even, generally content, until last month, when some kid bought a copy of a translation of Madame Bovary I’d published. He was a handsome lad, a university senior. That all seems fairly innocent, am I right? How soon fortunes turn, you better believe it! This kid took Madame Bovary around to the villages, preaching it to peasant girls before proceeding to make love to them in the hay.

Why Madame Bovary, you might ask? Why not Sentimental Education?

In his fine hands he had turned Madame Bovary into a cautionary tale against the rural petite bourgeoisie. He whispered to them sweet nothings of their right to individual freedom. He sang to them ditties about anarcho-feminism and anti-statist Marxism.

As if they could tell an elbow from an arse!

But their hearts were kindled when with great restraint each time he stopped thrusting his hips against their flailing bodies during the climactic instant of copulation to demand: Do you want to go the way of Emma Bovary?

Only when they had formed the following sentence would he resume his pelvic locomotion: I do not want to go the way of Emma Bovary!

Kid was making a killing.

Having amassed some fifteen to twenty girls with my paperback edition he brought them to Beijing. Now they were affiliated with the university’s anarchist student group. In the day, his bevy of besotted rustics were coached in maxims of libertarian socialism. By night: rice wine orgies and folk punk sing-alongs. When the sit-in at Tiananmen Square began, they descended on the promenade with much ado. Even if you don’t understand the principles, you can still chant democratic slogans, am I right?

Now that things have turned ugly, now that the Party has fired on student protestors in the streets, now that those still alive have been taken into interrogation – these peasant girls, when asked what they were doing there, what do you think their answer was?

Madame Bovary.

So the Party got ahold of a copy of the book and traced Madame Bovary to my publishing press. With some digging they find out that I helped produce Cui Jian’s Rock ‘n’ Roll on the New Long March album, but hey, give me a break, this was before they’d banned the guy’s music. How the hell should I have known that ‘Nothing to My Name’ would catch on as the youth movement’s anthem? I was pally with his Hungarian bassist, that’s all. We were drinking buddies at foreign embassy parties.

That does it for them. I get called in for questioning.

When I see what they’ve written on my file – ‘The Sole Purveyor of Madame Bovary in Beijing’ – I start to laugh. But I shut up real quick when I see their faces.

Heaven is blind. So is the Party. Don’t quote me on that.

I wasn’t protesting at the square or in the streets. Never even popped by out of curiosity. But what do they care? They tell me I’m in cahoots with what’s transpired. They show me a copy of the book. And I realize that dog turd had photocopied my Madame Bovary – a terrible copy at that, pages misaligned – so I hadn’t even earned the royalties off these dissident wannabes. Naturally, all these student activists are silk purses born after the famines, the purges, the sending-downs that we old-timers ploughed through like farm pigs just a generation ago.

In the blink of an eye trouble is nigh.

I’m blacklisted. I’m denounced, in turn, as a Western-loving imperialist, a revisionist, an anarchist, for translating, printing, and distributing Madame Bovary in China!

*

Excuse me sir, Bébé interrupted. What has happened at Tiananmen Square?

He gawped at her.

Are you living under a rock, baby sister? He was sweating from relating his travails with such force. Marseilles is far, but still. He wiped his forehead with the back of his hand. It’s a bad time, he went on, a snake year. If you don’t know anything, it’s better this way. The long line of ash from his cigarette broke off, dusting the motel pillow. She relit it for him.

Could you write it down for me?

Write what down?

The name of the author and the book you mentioned.

What do you want it for?

But Bébé did not want it for anything, so to that she had no answer. She’d never before read a classical Chinese novel in full, much less a European novel in translation. He studied her face. She did not look away. Slinging his hairy behind over the bed, he bent to retrieve a pen from his jacket. His ass cleft was the color of unhulled beansprouts. He turned back, depressing the end of the ballpoint pen against his chin.

福楼拜, he wrote on the back of the cigarette pack, 包法利夫人.

He tossed it to her. As he released the pen again on his chin with a satisfying click he said: We even republished this edition of Madame Bovary with a note from the translator, to say that Flaubert is not a capitalist. Well, he is a rentier, but his sympathies lie with the people. But did they see my effort with that? Of course not. Listen to me, girl. People only want to see the worst in other people.

What will you do now? Bébé asked.

I’ve got old friends littered all over the place. I studied literature in Paris when I was your age. Such a beautiful place, you can’t imagine! The old government paid for us to go. Of course now that’s all gone out the window. Zhou Enlai was my senior in the exchange program. Paris, Berlin, Munich, Lyon, London. It was so hard to travel then. Impossible unless you were born into money or you were a stowaway. Chairman Mao applied for the same work-study program and was rejected. I made it to Paris and he didn’t, ha! Where did that get the both of us?

He stopped to blow some air through his lips like a horse.

With a bit of grit and grease our kind can always start over, he continued. A noodle stand, or a hand laundry – stomachs are hungry and clothes will be dirty. A good coat can be made from gathering up enough poor scraps, yeah yeah. Something always comes up if you keep your eyes open. Hey, it’s good to see a homeland chicken so far from the old road. Nothing like a Chinese woman’s skin, you know?

*

Summer in Marseilles was turning to fall when the Corsican-Chinese Friendship & Trade Association took a pre-dinner aperitif with a prospective turf alliance: a Yéniche hashish gang.

The Corsican brought a multiracial selection of the bordello’s best to trick out the entourage – a Russian; an Algerian; Bébé. The meeting took place at an air-conditioned Italian restaurant on neutral ground. Bébé was in the bathroom when the Corsican made an off-the-cuff remark that greatly offended the Yéniche. She was pulling up her stockings when the shooting began. She kicked off her heels and headed for the kitchen. A sous-chef and kitchen boy were squatting, hands over heads, under the stovetop. She bolted through the service entrance.

Bébé did not know where she was running.

She did not stop until she hit a dirty canal. Her stockings were torn. She pulled them off and held on tight to the safety rails, trying to still the dry fire in her lungs. Throwing her balled-up stockings into the water, she startled a family of mallard ducks cruising in a V formation. She followed the ducks and the canal into town, sighted the main train station, and stole onto a train to Paris.

When she – Chinese, shoeless, in a skintight dress – got off at the Gare de Lyon, a patrolling officer asked to see her papers.

She shook her head. He clapped a hand on her shoulder.

Bébé began to cry. What she most wanted to tell the officer was that this was the first time she’d let herself cry in France, but she couldn’t, and he wouldn’t have understood anyway. Non parler français, she said. Parler chinois.

She was detained at a metropolitan police station.

The next morning, a police vehicle came for her. The rear windows were reinforced with wire mesh, and the height of the hard plastic seats had been specially designed such that detainees would have to cower to fit in the back.

Bébé was brought to a building with spotless floors and shown to a fluorescent-lit room. An immigrations officer, a pro bono human-rights lawyer, and a translator were waiting to take her statement. The lawyer shot up at once. She shook Bébé’s hand, and the translator followed suit. Bébé was served an inert bun and a small paper cup of scalding-hot vending machine coffee. She took the food quickly, burning her tongue on the drink. The heat of the coffee spread through her as she closed her eyes, pressing her fingers against them, and opened them again.

I was involved in what happened at Tiananmen Square, Bébé said. I took the last ship out of Beijing. I am a village girl from Taishan. I did not know much. I do not know much. A young man came to my village with an overnight bag. He was very handsome. In his overnight bag was a translation of foreign literature. He stayed a fortnight. In the day he read us Flaubert. In the evening he sang us songs, lay with us in the fields as the sun went down.

When he left the village, we wanted to leave with him. He took us to Beijing. At his university, they told us about freedom. They brought us to the sit-in. We chanted slogans in the streets. When the soldiers opened fire, some of my new friends died. The rest of us were dispersed. Someone said we’d be blacklisted for life if we were caught by the wrong people. We should leave while we could. So I left on a boat. From the boat we got onto a ship. The ship sailed to Marseilles. But I wanted to come to Paris.

In other words, the lawyer said, you have come to Paris as a refugee?

Bébé was unfamiliar with the word. The translator explained, in brief, the term to her. Bébé did not dare answer. She was trying to look for cues in the body language of the lawyer, to see if yes or no was the appropriate response.

I did not think it was possible that they read Flaubert in China, the lawyer whispered, close to tears. Tell us, what of Flaubert did you read?

Madame Bovary, Bébé said.

And how do you find the novel?

Bébé hesitated, lowering her eyes. The lawyer leaned over the metal table to touch Bébé’s hand encouragingly. She gave it a little squeeze.

I do not want to go the way of Emma Bovary, Bébé said.

Oh, the lawyer said, a tear falling down her cheek, bless!

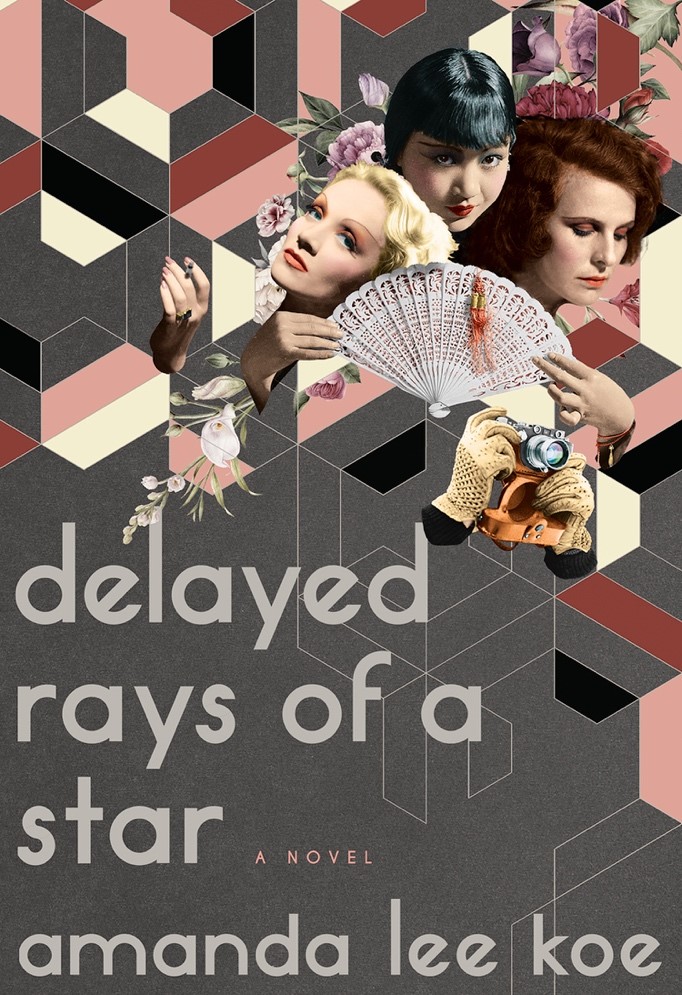

The above is an excerpt from Amanda Lee Koe’s debut novel Delayed Rays of A Star, available from Nan A. Talese/Doubleday in the US, and Bloomsbury in the UK.

Image © Rescued by Rover