The French distinguish between a rivière and a fleuve. A fleuve is a mighty river, defined specifically as one which flows into the ocean or the sea. It’s made of lots of rivers joined, and it defines its part of the world. The Severn and the Thames and the Trent may just about be fleuves, although English has seen no need of the word. But the Rhône is a fleuve, very much so. The Rhône is only just navigable. It is a great European artery, but not one you mess with. It often floods the towns along its course, a course that gradually changes anyway as the masses of gravelly sediment it carries with it settle and shift.

Historically, upstream movement was impossible in times of high flow. At best it was made by teams of forty horses pulling a load of less than a hundred tons: a month from Arles to Lyon (compared to the two–three days for the same trip downstream). In the mid-nineteenth century, an engineer called Claude Verpilleux (he was almost illiterate, but gifted for machines) designed tugs which rolled a pronged wheel along the river bottom, a bit like a funicular railway. Against general scepticism, the system worked and made a huge saving in coal. For nearly fifty years, Verpilleux tugs set the rate for upstream haulage.

Further south, the delta of the Rhône, like the delta of the Danube, is one of the great European geographic zones. It deviated the routes of travellers even before it set the routes of Roman roads. The Rhône valley as a whole defines something of France. The great wind of the valley, the Mistral, said always to blow in multiples of three days, has blown its way into the national character of the Midi, the French south. Madame de Sévigné called the Rhône: ‘Ce diantre de Rhône, si fier, si orgueilleux, si turbulent.’ (That dreadful Rhône, so headstrong, so proud, so troubled.’)

The source of this giant has been a place of great interest for a very long time. It rises from under a glacier – the Rhône Glacier is its unsurprising name – in the Valais, not far from Andermatt, in a region where a number of the highest Alpine passes radiate, and therefore where a number of routes meet. Travellers who wanted to go east or west had to duck under the snout of the glacier before climbing up the Furka pass or the Grimsel pass.

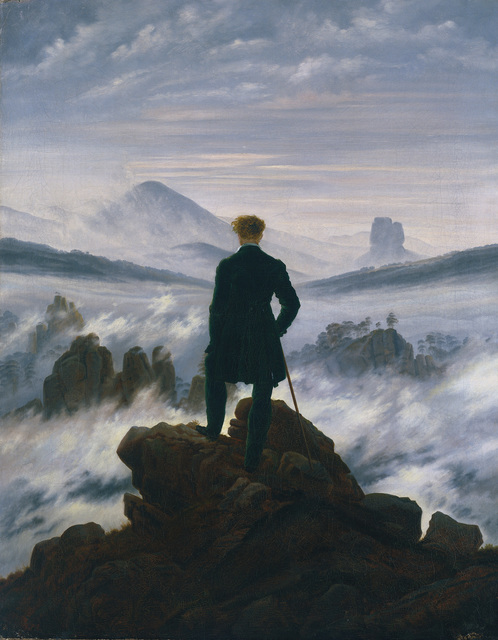

Caspar Wolf, The Rhône Glacier seen from the bottom of the valley at Gletsch, 1778

This is a continental watershed. According to a Master’s thesis on the Furka region by the architect Jan de Vylder, the ‘pass itself and the summits surrounding it, reaching an elevation of more than 3000m, form the watershed between three major European river systems: the Rhine (of which the Reuss is a tributary) which runs to the North Sea, the Rhône feeding the Mediterranean, and the river Po which connects to the Adriatic sea. A few km to the East is the origin of the river Inn, which is a tributary of the Danube and runs to the Black Sea.’By being sited so near the passes, the glacier has been curiously accessible (all such terms are relative in the high Alps, but still). For many, no doubt, it was just a dreadful obstacle. But for a few, it has been a source of wonder of a particular kind. Partly by its accessibility, the Rhône Glacier is one of the great monuments of the sublime, that peculiarly eighteenth-century sentiment cooked out of equal parts Enlightenment interest in the natural sciences, romantic laicism and the growing possibilities of travel. As Byron put it, in ‘Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage’,

I live not in myself, but I become

Portion of that around me; and to me,

High mountains are a feeling . . .

Burke, whose 1756 essay on it is so often given as one of the places where British thinking on the sublime was first decoded, quotes Milton describing the landscape that fallen angels must cross:

O’er many a dark and dreary vale

They passed, and many a region dolorous;

O’er many a frozen, many a fiery Alp;

Rocks, caves, lakes, fens, bogs, dens, and shades of death,

A universe of death.

That is the upper Rhône valley in a nutshell to the eye of eighteenth- or nineteenth-century travellers. As you craned your neck up to the high peaks, and as the sun disappeared over the ridges and dark came early to the valleys; or as you realised that you were above the treeline, and therefore above the familiar landscapes of the lowlands, a sense of awe became the required feeling for visitors. That awe finds expression in language close to that of religion. Here’s Shelley in 1816, writing of the river Arve, which flows through Chamonix in another part of the Alps:

Thus thou, Ravine of Arve—dark, deep Ravine—

Thou many-colour’d, many-voiced vale,

Over whose pines, and crags, and caverns sail

Fast cloud-shadows and sunbeams: awful scene,

Where Power in likeness of the Arve comes down

From the ice-gulfs that gird his secret throne,

Bursting through these dark mountains like the flame

Of lightning through the tempest

That’s not so very far from the language of the Book of Revelation.

Der Wanderer über dem Nebelmeer, Caspar David Friedrich

Carlyle – essentially a Romantic, although the historian and essayist that he became easily cloaks that – translated Ludwig Tieck’s Der Runenberg (1804), a tale on the wilder shores of the sublime that is both typical and fairly mad. The protagonist, like that of The Pilgrim’s Progress, is called Christian, and his journey is a mystical quest in which lumbermen and so on help him, but the mountains themselves affect his sensibility. Perhaps that’s enough; it allows us to skip all the frankly rather over-elaborate allegorical detail of his expedition into the high mountains. Think of Caspar David Friedrich’s solitary Wanderer, a gentleman in a frock coat, monarch of all he surveyed, staring down from the moderate peak that he simply cannot have scaled hatless and in town boots, to get the simplest impression of what the high mountains came to mean in the Romantic sensibility. And think that if Wordsworth could get a bit exalted about the Golden Valley above Tintern and his beloved Lake District, how much stronger the effect of high Alps might be. Goethe himself was a keen mountaineer, I remember, and with him Faust. Here, in 1833, is the first talking in the voice of the second:

Gazing at those deep solitudes beneath my feet,

I tread the mountain brink with deliberation,

Leaving the cloud-vehicle that carried me,

Softly, through bright day, over land and ocean.

These Romantic generations looked on the Alps and started to think beyond Romance. The mountains spurred them to geology – including the movement of tectonic plates; to climate; and eventually to the impermanence of Man and the ever-longer timelines that simply had to be true if fossils could be found at altitude.

Not everyone got it right. The critic John Ruskin was adamant that the power of glaciers was exaggerated: ‘A glacier scoops out nothing;’ he lectured to the Royal Institution in 1863, ‘once let it meet with a hollow, it spreads into it, and can no more deepen its receptacle than a custard can deepen a pie-dish . . . Full in the face of this same Rhône Glacier two impertinent little rocks stood up to challenge it. Don Quixote with his herd of bulls was rational in comparison. But the glacier could make nothing of them. It had to divide, slide, split, shiver itself over them, and ages afterwards, when it had vanished like an autumn vapour from the furrow of the Rhône, the little rocks stood triumphant and the Bishops of Sion built castles on their tops, and thence defied the torrent of the Reformation coming up the valley as the rocks had done the passage of the glacier coming down it.’

Much later, in 1924, Alfred Döblin, author of Berlin Alexanderplatz, published an extraordinary book of science fiction called Berge Meere und Giganten (Mountains, Seas and Giants) prophesying catastrophic conclusions that would come from human meddling leading to the melting of all of Greenland’s ice. The pendulum had swung all the way over. Glaciers had been symbols of majesty and mystery, of optimistic advance, and then by the time Döblin wrote – damaged by his experiences in the First World War – they became symbols of disaster on a global scale.

And that’s where they have stayed. Over the last few years, the retreat of the glaciers (and of polar ice) under global warming has been uncontestable. The subject is a staple of travel and eco-journalism, and a certain grant winner in research institutes around the world. There’s more ice tourism than our nineteenth century Romantics could have dreamt. There’s ice art as well as the more obvious ice science: the English research project Cape Farewell, for example, predicated on bringing boatloads of scientists and artists together to the North Atlantic, helped generate Rachel Whiteread’s memorable Embankment, seen in the giant Turbine Hall at the Bankside Tate, as well as chunks of pop songs, novels, film and so on. Ice is a catalogue of threat – a visible measure of the extreme climate disaster that we humans have willed upon ourselves.

As early as the 1870s, scholars were measuring glaciers as well as being awed by them. Even then it was clear that climate cycles varied, and that there might be a human element in the acceleration of global warming.

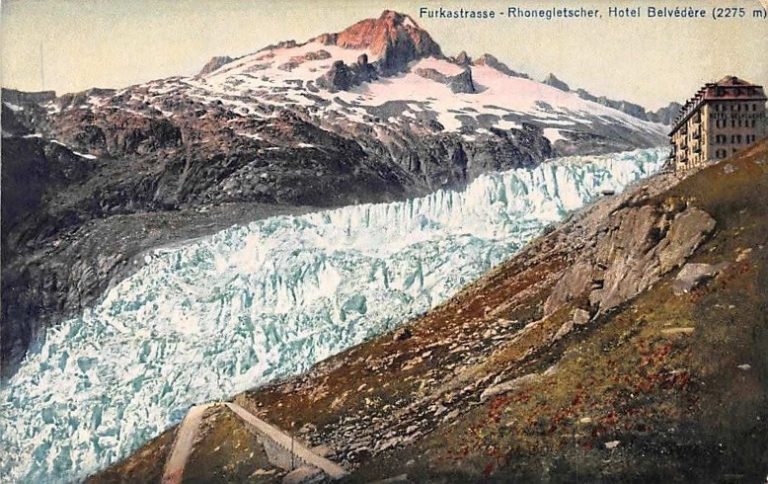

There’s a hotel high on the Furka Pass called the Belvedere, which was built specially to give access to that most touristic of glaciers. It was built by Josef Seiler and opened in 1882. Seiler knew about Alpine tourism; he was of that Seiler family which in effect built the Swiss resort town of Zermatt, catering to and profiting from the English obsession with Alpinism. Seilers didn’t just build hotels. They invested in mountain railways to get people there, bought farms to feed them once they’d arrived, lobbied furiously for membership of town and regional councils. At the Belvedere, you could lean on the balcony of your room and look out over the glacier. Josef Seiler also owned a hotel in Gletsch (the clue is in the name: it simply means Glacier) just down the road in the valley, to mop up any business from people looking up at the glacier from below. The Belvedere became famous. So famous that Sean Connery as James Bond in his Aston Martin (rather sedately) chased Tania Mallett over the pass, right past the Belvedere, in the 1964 film Goldfinger.

One of the attractions was the road itself. A perilous concatenation of hair-pin bends, it was a thrill-seeker’s delight, and the Seilers made sure the buses ran up there full of guests to fill their high-altitude beds. It still attracts large numbers of cyclists and its fair share of motor tourists. The whole marketing concept of the GT car – the Grand Tourer – is based on the seduction that a sufficiently-comfortable car could take you touring over these passes like a pre-petrol grandee on the old fashioned Grand Tour, cocooned in your elegantly-scented leather seats and watching the view scroll in front of your comfortably insulated windshield. Many car advertisements have involved smoothly driving up roads like this: it’s what you’re supposed to imagine that you could do, or will do, when you’re actually stuck on the Périphérique or the M25 breathing in the fumes of the car in front.

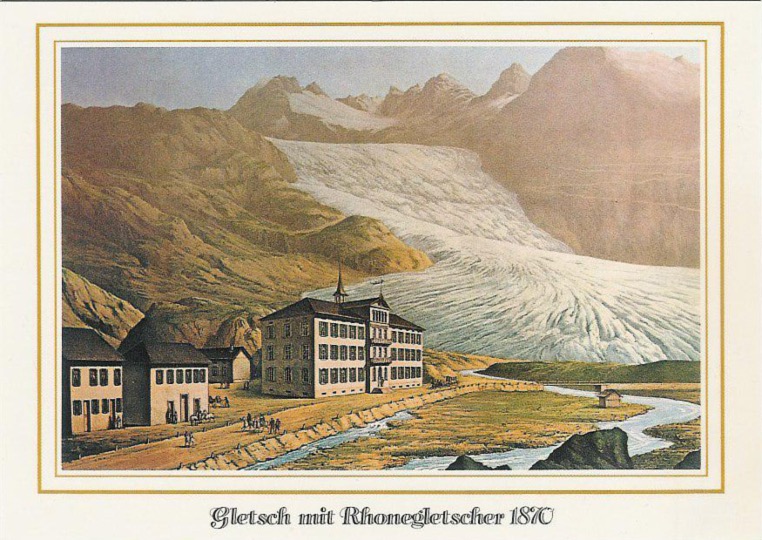

But the fame began to wane. Some say that as cars became more powerful, people could race through the Furka pass in a day rather than lingering two or three. Others note that exoticism moved elsewhere, and that Switzerland, even high-Alpine Switzerland, was simply left behind as travellers moved further afield. And the main attraction was plainly not what it was. Year by year, the Rhône Glacier melted. It used to reach right down to the valley floor at Gletsch, but it retreated. Now it doesn’t even reach past the Belvedere, perched on the shoulder of the pass, and the glacier has become an icy lake in its own collecting bowl high above the steeper sides of the valley. The hotel is closed, its future uncertain. Who wants to see a glacier that was once majestic?

But you can’t stop a process like global warming with a few blankets, even very expensive and high-tech blankets.

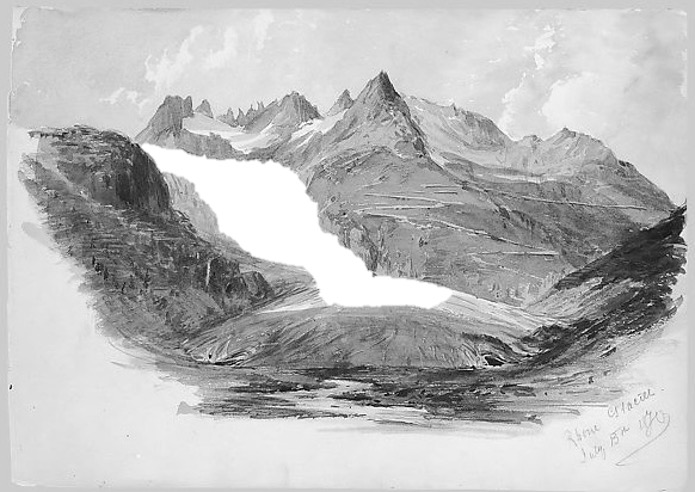

A sketch of the glacier by John Singer Sargent

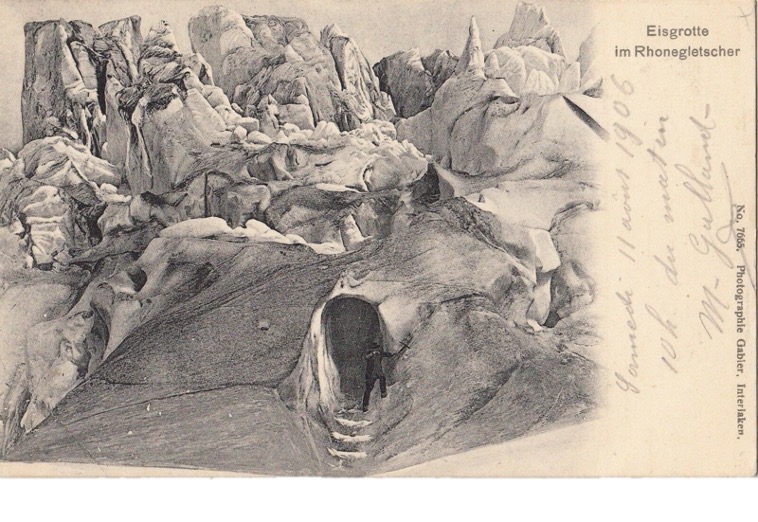

That’s the long story that Simon Norfolk and Klaus Thymann walked into when they became interested in the retreat of the Rhône Glacier, and began making the photos of their ‘Shroud’ series. The original invitation, I think, was Thymann’s – his Project Pressure has ‘Visualizing Climate Change’ as its strapline. They were by no means alone in finding it a powerful story to photograph. A number of agency photographers had worked there. Thymann himself had invited other artists. Nearly a generation before there had been an art festival centred on the Furkablick hotel, even higher than the Belvedere, and already in the mid 1980s some of the artists in that had been actively concerned with climate change, too. All of them work in the shadow of long lines of artists who have processed to the Rhône Glacier to marvel. Caspar Wolff painted the glacier in 1778 as a vast Sphinx claw, narrow on the descent and then spreading down the valley. Through the nineteenth century there are watercolours, engravings, lithographs. John Singer Sargent came as a teenager, on the itinerant holidays of his American expatriate family, up from the heat of Florence in the summer of 1870. Later, the postcard came to the glacier, along with the tourists, first by diligence and then by charabanc.

‘I’ve always found being in the presence of a glacier most haunting,’ Norfolk said, when interviewed for the Unseen Festival in Amsterdam recently. ‘Silent, withering, accusing. I’m fifty-five years old: my generation’s lifestyle burned away this ice. On a glacier, I always feel in some sense, guilty . . . The glacier seemed to be being wrapped in preparation for its own funeral. This life / death state-change interests me enormously. We photographed the shroud to resemble Carrara marble, which traditionally in western art has been used by the greatest artists to turn a lifeless stone block into the flowing liveliness of Sculpture. The ice of a glacier is made of water but looks and feels like hard stone. With time and the power of the ice, the strongest rocks on earth are plastic, as carve-able as butter. This glacier, which has existed for millennia, will die within the lifetime of children born today. None of the physics of my little, suburban life seem to be quite reliable when we get up there at high altitude, at greater pressure and at much, much longer timespans.’

Norfolk had worked with glaciers before, notably in an earlier partnership with Thymann, chronicling – by lines of fire – the erosion of the Lewis Glacier high on Mount Kenya. In that context, Norfolk had written

‘To be next to the ice is to feel privileged: like you are beside a colossal, sleeping giant. I imagine being close to a darted bull-elephant feels the same, and I’m reminded of seventeenth-century Dutch paintings of awestruck, bewildered Burghers contemplating a stranded whalefish. Close up one senses the glacier’s bulk, its coiled, dormant energy or its colossal longevity. And, of course, its cold, resigned indifference. One is hit by an overwhelming feeling of one’s own smallness and transience. Englishmen have been feeling this way about mountains for 300 years, since Romantic, Grand Tour travellers first astonished Swiss inn-keepers with the request for help in climbing to the heights. Nobody had done that before; for the fun of it, because it made you feel whole, because it feeds the soul. But this is the opposite – to think that in ten or twelve years this elegant, magnificent glacier will exist only in photographs is unbearable. The feeling I have for the losing of the Lewis can only be called grief.’

Norfolk’s work on Lewis is extraordinarily moving, and it won prizes. There are reasons for that. He knows grief and has thought deeply about it. He has been his whole career a photographer of the landscapes of grief. An early series was on the concentration camp at Auschwitz. Then Bosnia, Afghanistan, the Middle East. He made a project on the landscapes of genocide. He recently made a film on the nationalisation of death during and after the Great War, about the enormous cemeteries which made such a spectacle of public grief, but prevented individual families from bringing home their own loved ones. Norfolk is, in other words, an artist practised in tracking the elusive aura of places where death and dying have occurred on a huge scale. Planetary death – an emotive expression, and one that is bandied around much more than it used to be – is maybe the natural extension of that earlier work.

Thymann too was well prepared for the glacier. An environmental photographer of great experience, he is an experienced caver, mountaineer, diver. He learned many of those skills specifically to take groups of pictures, when those skills were what it would take to get them. Thymann is an explorer and expedition leader, who has worked on the underground rivers of the Yucatan, in Tonga, in Greenland, and he is also an investigative reporter. Those shrouds high on a mountain in the Valais were waiting for Thymann and Norfolk.