One starless night, I was stranded. Needless to say, foreigners are often stranded. I decided to translate the stories of eight girls who survived the Sancheong-Hamyang massacre, which took place in Gyeongsangnam-do, a southern province of South Korea, in 1951. My decision to translate the girls’ stories wasn’t entirely mine alone. It can take billions of years for light to reach us through the galaxies, which is to say, History is ever arriving. So it’s most likely that the decision, seemingly all mine, was already made years ago by someone else, which is to say, language – that is to say, translation – always arises from collective consciousness. Be factual, you say? As I mentioned, foreigners simply know. I will name the surviving orphans one by one in honor of the nameless children who are still homesick, captive, in detention, in internment, in concentration camps, in seas, in deserts, on Planet Nine, and such. And let’s not forget the children who are still in school.

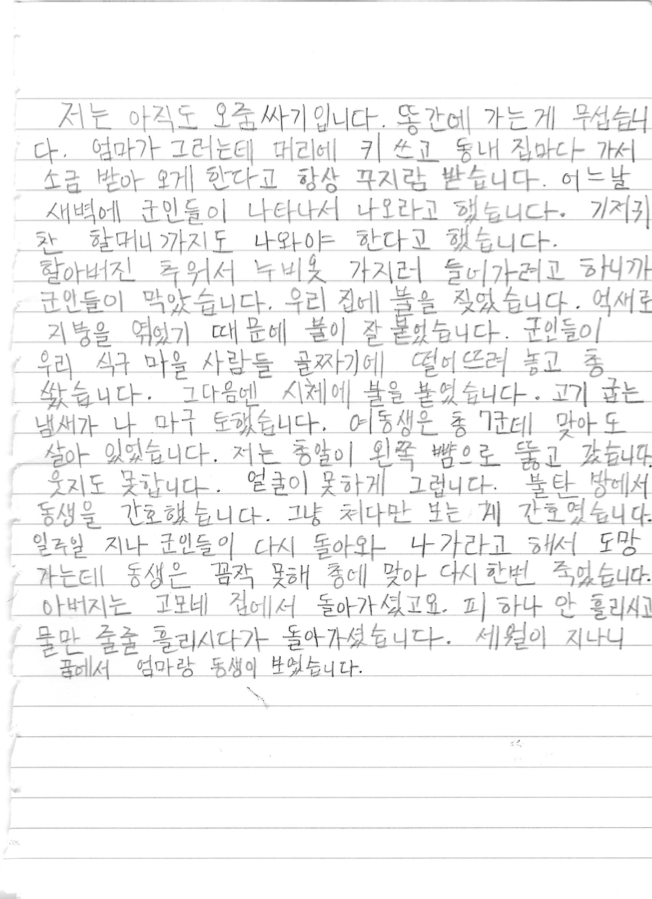

I still wet my bed. I was afraid to go to the outhouse. Mommy said she’d send me out with a winnowing shovel over my head and make me go from house to house and beg for salt. Soldiers appeared from nowhere and told us to come out, even my grandma in diapers. My grandpa wanted to go back into the house to get his quilted jacket but the soldiers stopped him. They set fire to our house. It burned fast because the roof was made of straw. The soldiers herded us into a ravine and shot us. Then they set the corpses on fire. The dead smelled like grilled meat, so I vomited. My sister was still alive after being shot seven times. As for me, a bullet went through my left cheek. I can’t smile. My face won’t let me. I nursed my sister in our burnt house. I just stared at the bullet holes on her body from morning till night. After a week the soldiers came back, and we fled. My sister couldn’t move at all, so she was shot again. She died the second time. My father died at our aunt’s house. He didn’t bleed at all. But water kept streaming out from his wound. It was as deep as the ravine. Months later I saw Mommy and my sister in a dream. Water. I couldn’t stop the water.

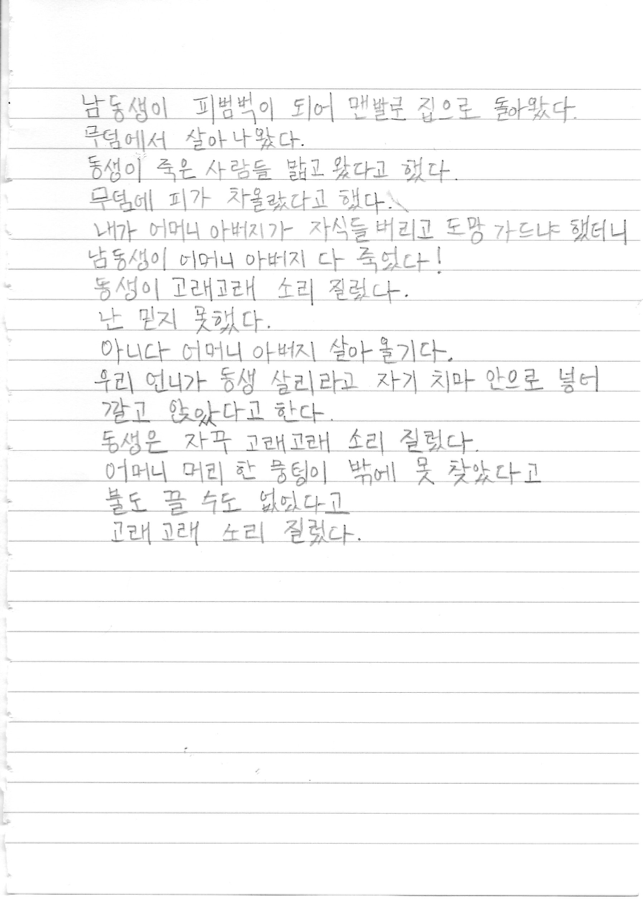

My little brother came home barefoot covered in blood.

He got out alive from the mass grave.

He said, I stepped on dead bodies.

The grave filled with blood.

I asked, Did our parents run away without us?

No they are all dead.

He screamed and screamed.

I didn’t believe him.

No they’ll come back alive.

Our big sister hid my brother under her skirt and sat on him to keep him alive.

He screamed and screamed.

I could only grab a clump of Mother’s hair.

I couldn’t put out the flames.

Father sizzled and crackled.

My brother screamed and screamed.

In a dream I chew and chew Mother’s hair.

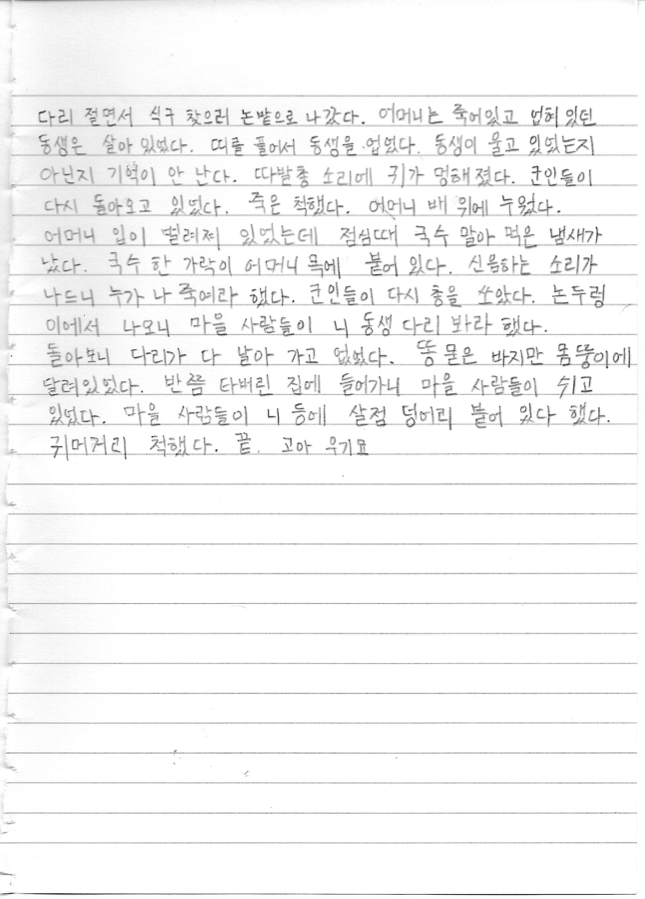

I limped out to the rice paddy to look for my family. Mother was dead but my baby brother on her back was still alive. He’d shat his pants. I untied him and wrapped him around my back. I don’t remember whether he was crying or not. My ears went numb after the machine guns went off. The soldiers came back to check. I pretended I was dead. I was on top of Mother’s stomach. From her open mouth I could still smell the noodle soup she had for lunch. A strand of noodle around her neck looked like a necklace. Someone moaned and said, Finish me off. So the soldiers started shooting again. When I came out of the trench, village people said, Look at your brother’s legs! I glanced over my shoulder. His legs were gone. I could only see his soiled, tattered pants. When I arrived home village people were huddled inside because their houses had burned down. They said, Look at the lump of flesh stuck to your back! I pretended I was deaf. The end.

I went on a tour of Ilya Kabakov’s School No. 6. It’s an imaginary school, abandoned in the desert just like an orphan. One famous critic said that the schoolhouse and the children represent the future, a utopia! No, this is not speech. I may be the only one who thinks this but representation can be magical. Cruelty and beauty – how do they coexist? I wish the eight orphans could have attended this school. They could have shown the Russian children how to make green noodles from camellia leaves. And the Russian children could have read to them their favorite fairy tale, ‘Snow White’. The guide told us that a big snake lives alone in the school courtyard among overgrown grass and dead trees no birds will perch on. What a void! But the music room was enchanting. There were many stories written by schoolchildren. They wrote about their class events, how they repaired their school, how they behaved on a trip to the museum and so on. Their notebooks strewn on the dusty wooden floors were not that different from mine – ‘discarded notebooks that no one needs’, according to the artist. I wish the orphan girls could have written their school stories too. I was thinking that the floors could use a good rubbing with sesame oil, the way children polished the floors at my old school, when I noticed a faded butterfly postcard on the floor. Another card next to it had pink roses. How perfect! The artist had thought of everything, as a child does. The roses looked like camellia blossoms, so I made a quick sketch for my mother. My mother always looked for camellia blossoms in our flight. I wish the orphan girls could have sketched the roses for their mothers too. I didn’t know Snow White also flew with snow geese. But that’s what the artist painted, pretending to be one of the schoolchildren: Illustration for the fairy tale by Ostrovsky, ‘Snow White’. In fact, he pretends to be all the children at the imaginary school while I pretend to be deaf. I may be the only one who thinks this but his translation of ‘The Snow Maiden’ as ‘Snow White’ is sublime. As I said, representation can be magical. Anyway, Snow White is displayed in the glass case of the school announcement board. I wish paintings of orphan girls could be on display, too, behind the glass. Then they could live forever inside a utopia! I wish and wish! It looks as if Snow White can touch the Milky Way! I wish and wish!

notes on the poems: The poems are imagined accounts based on what Dr Ahn-Kim Jeong-Ae, a former lead researcher in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Korea, had told me when I met with her in 2016. She also gave me a copy of the conference proceedings, Sancheong-Hamyang Massacres of Civilians (2011), which contain findings and analysis by Ahn-Kim as well as transcribed oral testimonies of the survivors. The year 2011 was the sixtieth anniversary of the massacre. ‘Orphan Nine’: I am referring to Boris Groys’ lecture, ‘Kabakov as Illustrator’ given on 12 October, 2002 at the opening of Ilya Kabakov’s exhibition, ‘Children’s Books and Related Drawings’, at the Chinati Foundation in Marfa, Texas.

Photograph courtesy of the author

These poems are excerpted from DMZ Colony by Don Mee Choi, published by Wave Books next month.