The conduct of the people of Sunderland was more suitable to the barbarism of the interior of Africa than to a town in a civilized country.

– Charles Greville, diarist and clerk to the Privy Council, November 1831

Dr Clanny stared down at the gaunt figure before him on the heap of straw, his professional calm masking his fears. Sunderland’s most eminent medical man, physician to the King’s younger brother and senior consultant at the local infirmary, had been called in to give a second opinion on this forty-year-old pauper woman, and he now found himself in the most delicate as well as frightening situation.

The woman’s own doctor had diagnosed typhus, but Clanny’s first glance told him that this was no case of the so-called ‘gaol fever’, common in these filthy lanes. But the doctor noted the patient’s constant vomiting and diarrhoea that had lasted for eight hours; the wracking cramps; the pinched, icy face; blue distorted fingers and toes; and the ‘corrugated’ skin of her hands – as though she had been washing linen. The signs all told a different story. And although Clanny, in over forty years of medicine, had never yet come across a case of the notorious cholera morbus, the scene before him was, he felt sure, indisputable proof of what the town, and the whole country with it, so dreaded and feared. No case of the disease had yet been confirmed on English soil, but it now seemed beyond dispute that the cholera had arrived and that Sunderland was its first port of call.

Earlier that summer, the physician had noted in his diary some strange happenings that he thought might have prefigured this disaster. First the neighbourhood had been invaded by great swarms of young toads, the likes of which had never before been seen in the town, and no sooner had they disappeared than the area was rocked by a series of powerful thunderstorms. And over the weeks to come, as the body count rose, the pragmatic Ulsterman William Reid Clanny, inventor of a safety lamp for miners, was also to ponder over the lightning strikes that followed the toads and the thunder. His deliberations were not based purely on superstition: the ancient Greek tradition of medicine in which Clanny was steeped taught that the weather was often linked to epidemics, and he was now struggling to apply his knowledge to this new and mysterious danger.

Now, though, he faced a more immediate dilemma. He was the most senior medical man on the local board of health, set up on the orders of Sir Henry Halford in London, and it was his duty to warn the government the moment the disease struck. As cholera moved steadily westwards across Germany that summer, Sunderland had known only too well that its huge trade with the Baltic ports just over the North Sea put it right in the firing line. Now that Hamburg had fallen, disaster seemed only a matter of days, perhaps even hours, away. Some of the townspeople were already whispering that the sickness among them was something quite different, something infinitely more terrible, than the usual, familiar stomach troubles that plagued them regularly in the autumn months. So far there had been only rumours, but Sunderland was at fever pitch, its population terrified not only at the prospect of the cholera itself but also at the financial hardship – destitution for many – from the quarantine on their port that would follow the appearance of a deadly foreign disease. A doctor would need more than his fair share of courage to diagnose a case of Asiatic cholera in this town; and, having done so, he had better be right.

‘I wished to avoid giving offence to any person, but at the same time I was impelled by an ardent desire to ascertain the nature of epidemic cholera in the face of every obstacle,’ Clanny later explained. ‘It is well known that more than half of our medical practitioners denied that any new disease had broken out in Sunderland. For a length of time our new epidemic was called simple diarrhoea, common cholera, congestive fever, typhus, etc.’

Sunderland sits on the bank of the river Wear, ten miles south of the great commercial port of Newcastle upon Tyne, the capital of north-east England, and twelve miles from the historic cathedralcity of Durham. In 1831, the town consisted largely of two long streets, the High Street and the Low. The High Street was a broad, cheerful place, lined with well-stocked shops and generally bustling with people, while the Low was narrow and winding, following the curves of the river, and packed with building yards, breweries and anchorsmiths. Small lanes ran off the High Street at right angles, and it was here that the great mass of the working classes lived, virtually all of them employed in the coal trade: as sailors; as keelmen, bringing coals down river to the ships in the port; as casters, hurling coals on to the waiting vessels, or in one of the countless jobs essential to keeping a huge tonnage of shipping on the seas. If the weather was fair, up to 200 ships might enter the harbour at one time, and their owners, anxious to turn them around fast, paid the labourers good wages. When the winter storms set in, however, the windows of the pawnshops in the lanes quickly filled up with any trinkets that would fetch a few shillings.

The western end of the High Street ran into the district called Bishopswearmouth, home to the better-off professional classes including Dr Clanny and most of his medical colleagues. In fact, as one of the doctors remarked, scarcely anyone of any status or influence in Sunderland actually lived in the town itself. By contrast, the extreme east end of Sunderland was dominated by the great barracks, base of the 82nd reserve regiment and home to 400 men, women and children, while in front of it lay the town’s slum quarter: a maze of foul-smelling alleys and tenements.

Clanny’s latest patient belonged to that world, and her circumstances, as well as the fact that the first doctor had misdiagnosed her illness, made the consultant especially determined to do his best for her. He ordered a strong infusion of lean mutton to be squirted into the woman’s rectum and held tightly in place with a wadded ‘T’-shaped bandage: ‘I directed that if the bandage were not sufficient, a tapering cork, well oiled, should be placed within the sphincter ani after a fresh injection had been thrown up.’ Eight hours later – to his great relief because the use of a cork to retain a liquid enema was certainly not standard medical practice – Clanny found his patient ‘much relieved in every respect’.

Little Isabella Hazard was not so lucky. The twelve-year-old lived in the Low Street near Fish Quay, where her parents ran a pub popular with the shipworkers. On Sunday, 16 October 1831, after twice attending church, Isabella went to bed in perfect health, but at midnight was suddenly struck down with vomiting, torrents of watery diarrhoea and an unquenchable thirst. Her eyes were sunk in their sockets, her features unrecognisable, her legs seized with terrible spasms, her pulse scarcely perceptible and her whole body freezing. Most alarming of all, her skin turned such a terrible dark blue that her mother asked the doctor, Mr Cook: ‘What makes the child so black?’ By four in the morning, Cook knew that he was out of his depth and sent for Clanny, who ordered a warm bath, brandy and hot water, mustard plasters to the legs, and an hourly dose of opium, ammonia and peppermint. On his return three hours later, the physician found no improvement in his patient’s condition. He ordered the treatment to continue, however, and saw the little girl again at 11 a.m., by which time the case was clearly hopeless. Isabella died at four o’clock that afternoon.

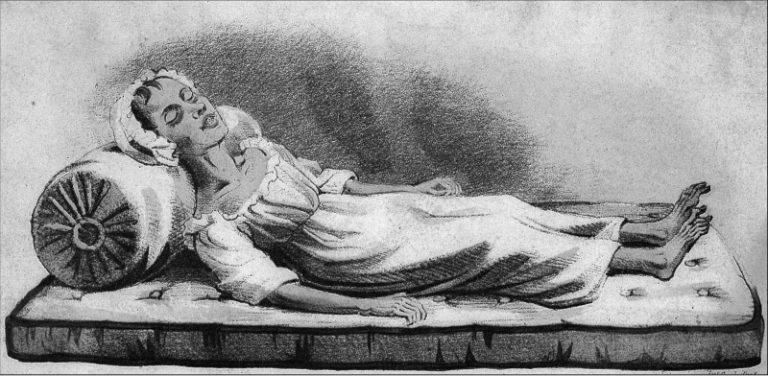

An engraving of Isabella Hazard after her death

Next to go was William Sproat, a tough sixty-year-old keelman, who had a large airy room in a house on the quayside, ‘a musketball’s throw’ in local parlance, from the Hazards’ pub. On Thursday night, three days after Isabella died, Dr Holmes was called out to treat him for a violent gastric illness and prescribed calomel and opium at bedtime and castor oil in the morning. A couple of days later Sproat seemed to be on the mend but then he had a violent relapse, which Dr Holmes blamed on the patient ignoring his advice about diet and having a mutton chop for dinner. By the morning of Wednesday, 26 October, Sproat was sinking fast and at noon he was dead. An hour later, his granddaughter, ten-year-old Margaret, collapsed by the corpse, and her father, William junior, ‘a fine athletic young man,’ according to Clanny, who had nursed his father day and night, was struck down the following day. Father and daughter were rushed to the local infirmary, where Clanny saw them both. William, he said, appeared as though he were ‘in a kind of drunken debauch’, thrashing wildly about and biting the bed clothes: ‘A vein was freely opened and about four ounces of thick black blood was extracted, which, on being left at rest, appeared like jelly.’ William died a few hours later.

The day after William and Margaret were admitted to hospital, Dr Clanny and his colleagues at the infirmary met in the boardroom to discuss the cases. They asked James Butler Kell, surgeon to the 82nd reserves and at that time the only man in town with experience of cholera morbus, to join the debate.

They were soon to regret their invitation. The army surgeon described what happened next:

The highly respectable practitioners stated their belief that it was the common cholera of this country, attended with aggravated symptoms, and that many cases of the disease, equally severe and some of which proved fatal, occurred in the month of August. I then explicitly gave it as my firm conviction that the disease under which Sproat and his daughter laboured was Asiatic cholera.

Kell went on to tell the gathering that he had already reported as much to the Board of Health in London, which caused something of an uproar among the highly respectable practitioners. Kell, however, who was not a man to be thrown off course by the sensibilities of a few colleagues, then explained his reasoning to the meeting, after which he ‘rested satisfied with the propriety of my proceedings’. No one else in the room was quite so happy with his conduct, however, and only Clanny agreed with his diagnosis of Asiatic cholera.

By now, on the quayside and up and down the alleys that ran between the High Street and the Low, they were dying in earnest. A fifty-six-year-old labourer named Robert Jordan who occupied a dirty basement in New Road breathed his last – like Sproat senior – on 26 October, just eleven hours after being taken ill. On Sunday, 30 October, the day before Sproat junior died, a thirty-five-year-old shoemaker called Rodenburg, who lived with his family in what his doctor described as a wretched hovel, ate a plate of pork for supper and went to bed in seemingly good health, but was then taken violently ill at about midnight. Dr Hazlewood described what happened next: ‘He was attacked with . . . violent cramps of the whole body, affecting the different fingers and toes successively; his voice was quickly reduced to a whisper, nails blue, skin livid and covered with cold sweat, pulse at the wrist imperceptible . . . At 12 o’clock, when being at his own request raised up, he instantly expired.’

The post-mortem findings on Rodenburg’s body make equally grim reading:

On opening the pericardium [membrane around the heart], the interior and superior venae cavae were observed greatly distended; these vessels and all the cavities of the heart were gorged with blood of a black colour and resembling tar; the blood was adhesive to the touch; and when the ventricles were laid open, they appeared as if treacle had been poured over them . . . The mucous membrane [of the stomach] was thickened and so soft as to be easily peeled off and torn with a nail. The prominent parts of the corrugations exhibited a black tinge, as if a paint brush dipped in Indian ink had been passed lightly over . . . On continuing our examination downwards, the fluid [in the intestine] became much whiter, precisely resembling a strong solution of soap, and where thinner, of whey, containing numerous white flocculi. In the caput caecum coli [part of the colon] the fluid had much of resemblance to pus.

The day after Rodenburg died, another keelman, fifty-one-year-old Thomas Wilson, was struck down. One of Dr Clanny’s colleagues at the infirmary, a physician called John Miller, wrote up the case notes:

Wilson was attacked on the morning of 31 October, about 4 o’clock . . . Mr Cook, surgeon, was called for at six o’clock . . . At seven o’clock I was called to him; pulse at this time not distinguishable at the wrists; skin over the surface of the body cold as death; lips blue; eyes dim and sunk in the head. Did not vomit; complained of intense pain in the epigastrium and abdomen, with cramps of the extremities . . . Extreme restlessness, moaning and sighing; speaks in a whisper . . .

The spasms ceased about nine o’clock; no vomiting or purging. There appeared a total loss of power of the nervous and circulating systems, and it appeared evident that the man must die. I left him, and saw him again at 12 o’clock; had the appearance of a living corpse. Eyes deeply sunk in their sockets; hands and fingers remarkably shrivelled, very much reduced in size, of a light blue tinge. He gradually got worse and expired at three o’clock in the afternoon.

Wilson was followed by Eliza Turnbull, a nurse at the infirmary who died just a few hours after laying out Sproat’s body. Betty Short went to her grave a week later and Robert ‘Jack’ Crawford, a forgotten hero of the 1797 naval Battle of Camperdown, the day after that.

The medical men did their best, putting the victims through every possible combination of torments. Betty Short, for example, whom Dr Hazlewood and a local surgeon, Mr Mordey, had discovered crouched by the fire, her knees drawn up to her chin and an overflowing bucket by her side, was subjected to what the doctors described as a very varied treatment, including brandy, laudanum, calomel, cajeput oil, rhubarb, jalap, turpentine, bleeding to eight ounces, a mustard poultice and a turpentine enema. Like Mrs Short, Robert Jordan was also dosed with brandy, laudanum, calomel and turpentine, but in addition he had to endure ammonia, sulphuric ether, scalding bricks on his feet, hands and stomach, and bladders of boiling water on his head. Rodenburg fortunately managed to escape proper medical attention for much of his illness and consequently received only brandy, laudanum and ether before he died. A visitor from London commented: ‘A Chinese mandarin, who has to swallow simultaneously the separate medicines ordered by each of the scores of his physicians, was never more copiously or heterogeneously drugged as are some of these unhappy creatures.’ And in nearly every case, it was all for nothing.

By now, in Dr Clanny’s eyes the medical evidence in favour of Asiatic cholera was beyond dispute and the time had come for Sunderland’s medical profession, and the rest of the town with it, to face up to the truth. When nurse Eliza Turnbull had virtually dropped dead in the infirmary from such a seemingly obvious source of infection as Sproat’s body, panic ran through every class of Sunderland society, and it was becoming increasingly untenable for the doctors to continue diagnosing these terrible deaths as a severe form of common cholera. Clanny decided to call his colleagues together to thrash out their differences once and for all about what, exactly, it was that they were dealing with. The medical men duly met again, fresh from a post-mortem examination on the ravaged remains of the once-athletic William Sproat junior. To the consultant’s great relief, this time they voted unanimously in favour of the motion he had put before them: ‘We have the continental cholera among us.’ It was the first such announcement on British shores.

By nightfall, Clanny’s official notification, as opposed to Kell’s informal report, was on its way to London and the response from the Privy Council, ready and waiting, was swift. Robert Daun, veteran of the cholera morbus of India, not to mention the more recent dramas of Hull and Port Glasgow, and the Board of Health’s favourite safe pair of hands, arrived post-haste from the capital with his by-now familiar brief to discover just why people were sickening and dying. This time, however, the Lords of the Privy Council appeared fairly sure that they knew the answer already, for hard on Daun’s heels came the redoubtable Lieutenant-Colonel Michael Creagh, later Sir Michael. Creagh’s orders were clear and his resolution firm. As soon as the officer set foot in town he sought out Dr Clanny and then, after crashing in on Kell and Daun while the latter was finishing his breakfast in Kell’s lodgings, announced an immediate fifteen-day quarantine on all vessels leaving the Wear for domestic ports, enforcing his proclamation by stationing a warship just offshore in case anyone was in any doubt about the matter.

Kell felt himself vindicated. His experiences of the disease in Mauritius in the 1820s had convinced him that cholera was highly contagious and could be caught from clothing and bed linen, as well as passed on by direct person-to-person contact. He had already caused a row about a river pilot called Robert Henry, who had died in September from what Kell was convinced had been Asiatic cholera, and he had long been warning about what he saw as Sunderland’s laxity over the quarantining of ships from foreign ports. He had previously called for a brig of war, or at least heavy artillery, at the entrance to the river to enforce the regulations. No one had paid much attention at the time, and even after the death of Isabella Hazard, the army surgeon had uncovered more evidence of what, to his military mind, was a severe dereliction of duty by the port authorities and a threat to ‘the safety and happiness of the population of the Empire’.

At the request of one of the local surgeons, Kell had gone to see a seventeen-year-old lad called Dodds who was close to collapse. Dodds told Kell that he had been in perfect health until the previous night when he was suddenly seized with the most appalling symptoms, and it was this violent onset, so characteristic of Asiatic cholera, that worried Kell. Dodds worked in a shipwright’s yard on the river bank at a place called Deptford, where several ships were anchored under quarantine, and the conscientious Kell lost no time in going to see the situation for himself. He was not reassured by what he found: ‘There were three or four ships in the river with the yellow flag; the tide was out, the water shallow and from the want of a marine, police or military guard, I could not discover how the intended seclusion could be carried into effect.’

But while Kell considered Creagh’s new measures to be the very least that the situation demanded, Sunderland’s merchants and shipowners were outraged over what they saw as the government’s ridiculous, not to say damaging, over-reaction. A week after Daun and Creagh’s arrival, the local newspaper was still insisting that nothing was amiss in the town. ‘That five persons expired is true, but there are doubts as to the causes of their deaths,’ said the Sunderland Herald, ‘and had it not been for the too-zealous communications of some alarmists, it is more than probable that the inhabitants of Sunderland would have been represented as having the enjoyment of more than ordinary health.’

There were no more patients than usual in the infirmary or on the local doctors’ books, the paper’s editor maintained. He then went on, in the best journalistic tradition, to overstate his case: ‘In fact, the general appearance and gaiety of the inhabitants of these towns were never more apparent. No one hides or shuts himself up as if inhaling an atmosphere charged with deadly contagion; they assemble in groups and are as busy . . . as at any former period; and the theatre continues open.’ Any sickness that did exist was clearly no more than the usual maladies that affected the poor. He believed they had only themselves to blame, for he had it on good authority that that part of town where the so-called ‘destructive malady’ was most prevalent was ‘inhabited by persons steeped in poverty through dissipation and idleness’.

Despite the strident views of the Sunderland Herald, clearly something of a Daily Mail of its time, on 8 November Colonel Creagh informed London that Daun was convinced beyond all doubt that the disease killing people in Sunderland was ‘the epidemic, malignant cholera’, adding that he was sorry to say that it was now spreading fast. The Herald was certainly right in one respect, however: the slum streets were definitely being hit hardest, a fact that Creagh, for one, found encouraging. If cholera flourished in dirt and decay, he reasoned, then controlling its spread should be an easy matter. Almost at once, the energetic colonel had the fire engines out washing down the streets, backed up by an army of men with brooms, scrubbing years of accumulated filth from the gutters and gullies. At the same time, he procured a pipe (114 gallons) of brandy and laudenam, and piles of blankets for distribution to the poor.

Both he and Daun, neither of them squeamish men, were appalled at the conditions they found tucked away behind the prosperous bustle of the High Street. ‘I believe that in no other town of the Empire is there to be found a pauper population so dense as there is in some parts of Sunderland,’ Daun wrote to his friend Sir Edward Seymour. ‘In the lanes and narrow alleys, every room, from the cellar to the garret, contains a family averaging from four to five persons in the most abject state of poverty.’ He was particularly moved by Rodenburg’s pitiful home, which he visited after the shoemaker’s death: ‘The room of Rodenburg measured eight feet by ten and had served the poor man as a kitchen, boot shop and bedroom for himself, his wife and four children.’

Despite their determination, the two emissaries from London soon found that organising a clean-up and supplying the poor with a few creature comforts were the easier parts of their task. Blankets and clean streets posed no threat to anyone. Obtaining accurate medical reports and opening a designated cholera hospital, as the Privy Council had instructed, were different matters, however, and here the pair met with a wall of obstruction. Daun designed a form for recording all cases of cholera morbus, common cholera and simple diarrhoea. The doctors were asked to list each patient’s age, sex, symptoms, circumstances, occupation, alcohol consumption, and whether he or she was currently sick, recovering, cured or dead. Daun announced he would send an orderly to every doctor’s home each morning between 10 and 11 a.m. to collect the newly completed forms for the previous day and would then use this information to compile his own daily report for the government.

It seemed a good plan. The drawback was that the only man in town prepared to fill in his forms with any attempt at accuracy was Dr Clanny. And while Daun, like Creagh, was convinced that vested commercial interests lay behind this lack of co-operation, a few days’ acquaintance with his Sunderland colleagues had him wondering whether some of them were intellectually or medically capable of complying with his request. He was particularly withering about the parish surgeon Mr Embleton, who, to Daun’s disgust, turned out not to be a surgeon at all but a mere apothecary. ‘He is evidently that sort of half-educated practitioner with whom I would find it very unpleasant, as well as difficult, to act,’ Daun complained.

By 15 November, a full month after Isabella Hazard had died, Daun and Creagh finally had a cholera hospital open for business, thanks largely to the efforts of the Reverend Robert Grey, Rector of Sunderland, who, Daun said, had been ‘indefatigable in doing good’. Ironically, Grey was to die a few years later of another nineteenth-century killer, typhus, that he caught while ministering to the poor in the back alleys. Daun moved into new lodgings close by the hospital so that he could keep a constant watch on what was going on there. His next difficulty lay in persuading the sick to enter its doors. With echoes of Berlin and St Petersburg, a rumour spread around town that the body of a woman who died in the hospital was so horribly mangled during a post-mortem that when her coffin was opened at the graveside, the appalled mourners found practically nothing of the corpse was left.

Not a word of this was true, according to Daun. ‘Another story, equally current, is that the woman was not dead when the surgeons began to open the body and that she even called out to them to spare her,’ related the doctor, at the end of his tether. ‘What can one do in such a case? No more dissections shall be made but I fear the mischief is already done . . . There are several families in Mill Street of the poorest class afflicted with this melancholy complaint, but they evince the greatest aversion to being moved to the hospital . . . and prefer dying in the midst of poverty.’

In the meantime, the local businessmen had not been idle in defending their town and their livelihoods from the outrageous slur that they had a foreign killer disease in their midst. On 11 November, a mob of furious merchants and ship owners packed the Commission Room of Sunderland’s grand Exchange building, roaring their anger and denouncing the reports of Asiatic cholera as a ‘malicious and wicked falsehood’. They went on to pass a series of resolutions to be sent to the Privy Council. John Spence proposed:

That . . . the town is now in a more healthy state that it has usually been at the present season of the year and . . . as to the nature of the disorder which has created unnecessarily so great an excitement in the public mind throughout the kingdom, the same is not Indian cholera, nor of a foreign origin, but that the few cases of sickness and death which have taken place in the town . . . have in fact been less in number than generally occur and have arisen from the description hitherto known as common bowel complaints which visit every town in the kingdom in the autumn, aggravated by want and uncleanliness.

John Kidson followed this with the motion: ‘That the measures adopted by His Majesty’s Government in requiring the shipping sailing from Sunderland to perform quarantine and more especially in preventing . . . by a ship of war, all ships and other craft from leaving or entering the port is perfectly unnecessary and uncalled for, and more especially when it is considered that the transit of goods and merchandise of every description and unlimited communication by coaches and other means by land is permitted [from the town] to every other part of the Kingdom.’ On this last point about travel by land, Mr Kidson had some logic on his side.

Then in a thrust at poor Kell, who was by now fast becoming a local hate figure, the meeting deeply regretted ‘that any individual, although actuated by proper and honest motives, should have given information to His Majesty’s Government of the existence of Indian cholera in Sunderland without having first clearly ascertained the fact, and without the knowledge and sanction of the principal inhabitants, and hopes that the opinion of this meeting will prevent in future a conduct calculated to bring such disastrous consequences, not only to this town but the country at large.’

Kell had decided not to go to the meeting, and when he learnt about the crowd’s ugly mood, he welcomed his lucky escape from ‘the unpleasant consequences which might have resulted towards me in that tumultuous assembly’. By this time, the army surgeon had had enough. As he saw it, he had tried to do his duty for the sake of the town, but from now on he would confine himself to the job he was paid for: worrying about the health of his troops. He withdrew behind the walls of the great barracks.

The civilian doctors also felt the wrath of the meeting. In a clear threat to their pockets, the businessmen voted to publish the names of those medical gentlemen who had supported the idea of informing London that the cholera was among them. The meaning was not lost on the doctors: anyone on the blacklist would suddenly find himself very short indeed of wealthy private patients. Consequently, an even more extraordinary event was to follow. That evening the meeting reconvened, and sixteen of the town’s doctors stood up before it, one after the other, to deny the information that they had sent to London just days before. Their words read like recantations at a show trial:

Mr Dixon: ‘The continental cholera has not been imported into Sunderland and the cases of sickness which have taken place in Sunderland are aggravated English cholera.’

Dr Browne: ‘The cases of cholera which have occurred in Sunderland arise from the product of our own soil and entirely among ourselves and has not been imported and is not contagious.’

Mr Croudace: concurs with Dr Brown.

Mr Watson: ‘English cholera only has prevailed here.’

Mr White: ‘Has not seen a case of Asiatic cholera in Sunderland’. Mr Ward: ‘The disease in Sunderland is not a contagious disease and not more aggravated than the epidemics of the four previous autumns.’

Mr Smithson: ‘The Asiatic cholera has not taken place in Sunderland.’

Mr Greene: ‘The cholera which has appeared in Sunderland has no foreign origin.’

Mr Ferguson: Dissented from the report forwarded to government by the medical board of this town and does not think we have any Asiatic cholera in this town; and believes we are in a more healthy state with the exception of an epidemic of English cholera than we are generally in this season of the year.

Mr Gregory: Dissented from the proceedings of the medical board of this town from their first commencement. We have no disease in this town which he considers Asiatic cholera or any contagious cholera whatever.

By now the rest of the country was looking on aghast. Worried by the damage being done to the reputation of Sunderland’s medical profession, an exhausted Dr Clanny called his colleagues back together for a third time within days and between them they concocted a fudge of a statement, aimed at restoring some of their credibility while at the same time keeping the businessmen sweet. They declared that a disease with every symptom of epidemic cholera was in the town, but there was no reason to suppose it had been imported or was contagious. Rather, it seemed to have arisen from something in the atmosphere that had affected people already weakened by lack of proper food and clothing, or from breathing bad air, or from drunkenness or pre-existing disease. And for good measure, they added, stopping trade would do more harm than good by depriving the poor of their livelihoods and putting families in distress.

This was a statement that Clanny at least could sign with a clear conscience for, unlike Kell, he had never believed cholera to be contagious. He was convinced that the disease – which he called hyperanthraxis because he thought the colour of the patient’s skin resembled coal or anthracite – stemmed from an excess of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, and he slept with his bedroom door ajar to avoid a build-up of the gas.

The medical gentlemen then went on to express their hope that their latest pronouncement would ‘remove any misconstructions and false reports which have arisen out of this unpleasant affair’ and for good measure, they ended by congratulating their fellow citizens on the otherwise good health of the town.

The Privy Council, completely out of patience with these antics and bombarded almost daily with complaints from Daun and Creagh, responded by drafting in another big gun. Dr David Barry, fresh from the devastation of St Petersburg, was ordered to Sunderland. ‘You will immediately institute a careful inquiry for the purpose of removing all doubts as to the nature of the disease existing in that town,’ his instructions from the Privy Council ran.

You will communicate with all the medical profession and obtain from them all the information they may be able to afford you. You will state to them that you have been dispatched by His Majesty’s Government for the express purpose of making these enquiries, and you will require to be furnished with an accurate statement of all the cases which they may have seen of diarrhoea, common and malignant cholera, with a statement of every new case, and you will require to be personally summoned to such as are of an alarming nature.

The very night that Barry arrived he stumbled upon a case that disturbed him. A mother and two children were lying sick and helpless in a ‘miserable habitation’ with no food, with one single blanket that they had only just been given, and with a third child lying dead in the room. Such was Barry’s influence by now that the Privy Council at once dashed off letters to the Chief Magistrate and the Bishop of Durham demanding an inquiry. On 27 November, Barry wrote again to London, but this time the Privy Council was unable to put the matter he raised so quickly to rights. Barry confirmed that the disease now killing people in Sunderland was identical in every respect to that which had so haunted him in St Petersburg.

By now the town’s leading physician, Dr William Reid Clanny, was worn out with work and worry. The sixty-one-year-old consultant had not spared himself – Kell referred admiringly to his ‘devoted zeal and anxiety’ – yet for his pains he was finding himself almost as vilified as the army surgeon. But while Kell was condemned for irresponsible scaremongering, Clanny was accused of the opposite crime of organising a cover-up. He later wrote about the events, trying to vindicate both the town and himself: ‘We met the shock with manly firmness,’ he insisted, ‘. . . though, from unavoidable causes, our success was not what it ought to have been,’ adding sadly: ‘How far I have deserved the calumnies which in certain quarters have been so lavishly heaped upon me, an enlightened and liberal community will now be enabled to judge.’

By 3 December, seven weeks after cholera first struck, the number of cases in Sunderland stood at over 300, and fourteen new patients were being diagnosed each day. Not one of the soldiers under Kell’s care, or their wives or children, was among the casualties, however; the surgeon, acting on his conviction that cholera was contagious, had ordered the barrack gates locked as soon as the disease began to spread and had forbidden the families any contact with the town. But for the rest of the country, the prognosis was grim. The day after Barry identified cholera morbus in Sunderland, he and Daun were on their way to Newcastle, ten miles distant, where the mayor had just reported what was believed to be a case of Asiatic cholera, the victim dying in nine hours. On Christmas Day the disease struck at Gateshead, just south of the Tyne, where ‘the malignity of the pestilence was truly appalling,’ according to the Lancet. While Sunderland’s businessmen threatened and blustered and its doctors vacillated and lied, the killer had broken loose.