‘You must dive naked under and deeper under,

a thousand times deeper. Love flows down.’

– Rumi, ‘The Silent Articulation of a Face’

translated by Coleman Barks

1. The Line

There was a line in the lake where it went from transparent to opaque. This was where the basin suddenly dropped from twenty metres to almost 300, making this oldest of Europe’s lakes also one of its deepest.

As below, so above: this abysmal descent was perfectly echoed by the vertical peak that rose to 1,000 metres above the inlet where our little boat was moored. The peak was called Big Shadow and was part of the karstic mountain that cast its chill over the eastern side of the lake. From where I had swum out, I could see the crumbly niches in Big Shadow, where hermits had lived for a thousand years. The last resident hermit, one Kalist, had been spotted in 1937, in a cave accessible only by rope ladder. The early anchorite monks and nuns lived on roots and berries, rarely leaving their eyries or breaking their silence, the changing colours of the lake their daily contemplation.

The chalky mountain separates the lake from its higher, non-identical twin, but only overground. Underground, they are connected. Ohrid and Prespa: two lakes, one ecosystem. The water of Ohrid (hard ‘h’) is famous for its translucence. On a late summer’s morning, it appeared immaterial, unearthly – not so much water as the essence of water – and its temperature made it inseparable from your skin. You could be swimming through air. Reflected clouds hung in the water and moored boats levitated in space. On such mornings, time became illusory and the distant became present. There was a magical, almost quantum feel to this lake, and it was understandable that many believed it was inside an ‘energy vortex’.

Lake Ohrid is Europe’s largest natural reservoir of clean water, but its ethereal quality was partly the work of Lake Prespa and the mountain. The porous karst allowed underground streams to flow from the higher to the lower lake and they filtered the water like a giant sponge, so that when the underground rivers of Prespa came out at Ohrid in the form of multiple springs, the water was newly born. Further sublacustrine springs fed the lake. Swimmers who came out of the lake had a particular expression: for a short time, they took on the quality of the water. They looked completely at peace.

I knew about the sudden drop in depth, but not its exact location, and anyway it’s easy to forget everything you knew on a brilliant-blue sunny day with no separation between air, lake and mountain, when you’re floating in coastal waters off the inlet of Zaum in a state of bliss. My boat guides, two sisters, had moored for lunch here, where the medieval church of Mary of Zaum with bat-shit-encrusted but lifelike frescoes sat just metres from the water under weeping willows. Here was a depiction of a bare breast, rare in the Eastern Orthodox canon: Anna in a robe of deep red breastfeeding Mary. And the earliest-known portrait of St Naum, patron-protector of the lake and healer of the insane.

The St Naum Monastery was a quick boat ride south of here. Five centuries before, it had been established in the ninth century by the Bulgarian monk Naum – viticulturalist and ‘miracle-maker’ – on a piece of land sitting atop numerous springs. Naum’s arrival marked a long period of Slavonic cultural efflorescence on the lake. This was followed by a Byzantine efflorescence and with the later arrival of the Ottomans, a rich culture of Sufism, some of which still survives. And because the people of this intricate landscape were organically suited, and millennially devoted, to the mysteries of nature, the result is a continued syncretic approach to all worship and ritual. Nature remains the original source of the sacred, beginning and ending with water.

The lake is surrounded by healing springs and wishing wells. The largest are the St Naum Springs at the southern tip of the lake shaped like a perfect oval mirror. At the northern end is another healing spring, on top of which perch niches and painted cave churches. Their patron is the resident icon of a Black Madonna. Believed to cure infertility and blindness, like the spring, legend tells how she’d been thrown into the lake many times by ill-wishers, but each time, she’d swum back to the spring. The Black Madonna of the lake is still worshipped on special days by Macedonians and Albanians alike, including Muslims. People kiss her, leaving hundreds of lip marks on the protective glass. The lake also has another, secular protector-spirit – a fictional woman called Biljana, from the lake’s anthem ‘Biljana washed her linens in the Ohrid springs’. Biljana was washing her linens when a caravan of vintners passed. She warned them not to crush her linens. They promised to repay her in wine, but ‘I don’t want your wine,’ she said, ‘I want that lad over there!’ But the lad was betrothed, and Biljana was left in the icy springs – disappointed but at least in charge of her linens.

Not far from where I swam, an invisible line ran across the lake from the St Naum Monastery to the western shore: the Albanian-Macedonian border. Or North Macedonian, since the country changed its name in a painful trade-off with neighbouring Greece in 2019. The sisters had refused to take the boat beyond the border zone, which I couldn’t see but they could. It was a border of the mind but trespassed, it came with very real fines, and a confiscation of your boat licence. Yet the lake was open, boundless. And it had been this way for at least three million years; some scientists said five million. Either way, humans were recent arrivals in comparison.

From the St Naum Monastery, we could hear the Italian pop music of lakeside restaurants in the nearest Albanian village. We could almost smell the grilled fish. You could swim into Albanian territorial waters from the monastery’s beach, but you’d need a passport, and you risked being arrested by either side’s border police.

Because I am a confident swimmer, I’d gone quite a long way in from Zaum. I knew that you could see through the water down to twenty-three metres, and when I dived, I saw the long plants that grew from the bottom and reached for my legs, like the hair of the mythical samovilas. Samovila: a shape-shifting Balkan female entity that acts as the custodian of forests, mountains and lakes. She is seductive but you don’t want to cross her. That’s because the human being is a trespasser in her realm. Lake Ohrid had its own samovilas which would sing their siren songs to the fishermen, seemingly from within the deepest part, and by the time a rowing boatman found himself in the middle of the lake and realised that the song was in fact howling wind from the karstic mountain, it was too late – the weather had turned, all four winds of the lake had risen, there was the deadly undertow, subject to capricious subaquatic weather, and you were a long way from the shore. The catchment area of Ohrid is 2,600 square kilometres, but it has no islands. Once out on the lake, you are without shelter.

The deepest part was here, some thirty metres in a straight swimmer’s line from Zaum, and I remembered this when I suddenly couldn’t see through the water any more. Its colour had changed and, with it, the temperature. A chilly dark abyss gaped beneath me. A tomb. My body momentarily seized with panic. No wonder the traditional Ohrid boat resembled a coffin, with its raised square sides, its design unchanged since the time of the ancient Illyrians.

In that lonely moment on the edge of the precipice, just before I turned round and swam back, swallowing water because I’d clocked what a long way I had gone and my breathing was out of sync, in that moment I glimpsed the fathomless nature of water. Of my relationship with water, perhaps all human relationships with water, and what had really led me back here to the matrix, to this lake of lakes where my maternal family line had seeded somewhere in the depths of the genetic pool, and was reaching up to me, pulling at me with deadly playfulness.

2. The Dream

Though I grew up in an inland city, water has always been with me. In a dream I’ve had for the past thirty years, an immense body of water rises on the horizon and approaches me and the world as I know it. I am on a high shore. The water may not reach me, but it will reach others. I am terrified, but can’t stop watching the water make its majestic approach. This is not personal. It’s not even about any of us. It’s about the water and how it suddenly threatens our interests, when we thought it was our friend.

Sometimes, the dream ends there, on the brink of cataclysm. The collective dread, the belated astonishment rises in me – how come we didn’t see it coming? – and in that moment of no return I grasp that I knew, we knew it was coming, but chose not to see it. Other times the waters creep in, in an anticlimax of silence, and I find myself in a submerged world. Underwater, I recognise buildings, neighbourhoods and people. Everybody’s eyes are open now. There is no sound. I swim through the wreckage, looking for familiar faces. Pylons collapse.

For a time, I thought the imprint for this dream came from a childhood summer camp on the Black Sea, when I witnessed a storm with raging black waves and its aftermath – broken concrete on the beach, a dead dog and piles of seaweed and jellyfish. But recurring dreams probably come from more than one moment in time. They are symbols seeking to communicate across psychic realms. In archetypal terms, the sea symbolises the universal unconscious, ‘the mother of all that lives’ in Carl Jung’s words, with its contents submerged yet ever present. Physically too, we are mostly water. Our bodies are made of water. The primordial ocean contains all moments in time, and we spend our prenatal life in water, absorbing our mother’s nutrients and emotional-neural vibrations. That is why, even though your mother can be free of you, you can never be entirely free of her. In every holistic cosmological system of thought – from Daoism to Jung – water is feminine, or yin.

My mother and sister are afraid of deep water, mistrustful. By contrast, my maternal grandmother Anastassia loved water. She died when I was a child. There was, I always sensed, something distinctly thalassic about her. She came from here and carried the lake within her for the rest of her life. Anastassia had a radiant, but unstable, choppy-water quality about her. She absorbed to excess the energies of people and places, and had a deep emotional memory. As if she was more than one person, a whole nation of souls. She carried some original matrix where the land masses were still moving, the fault lines stirred under the surface, the water levels rose and fell, something was out of sync and could not be reconciled.

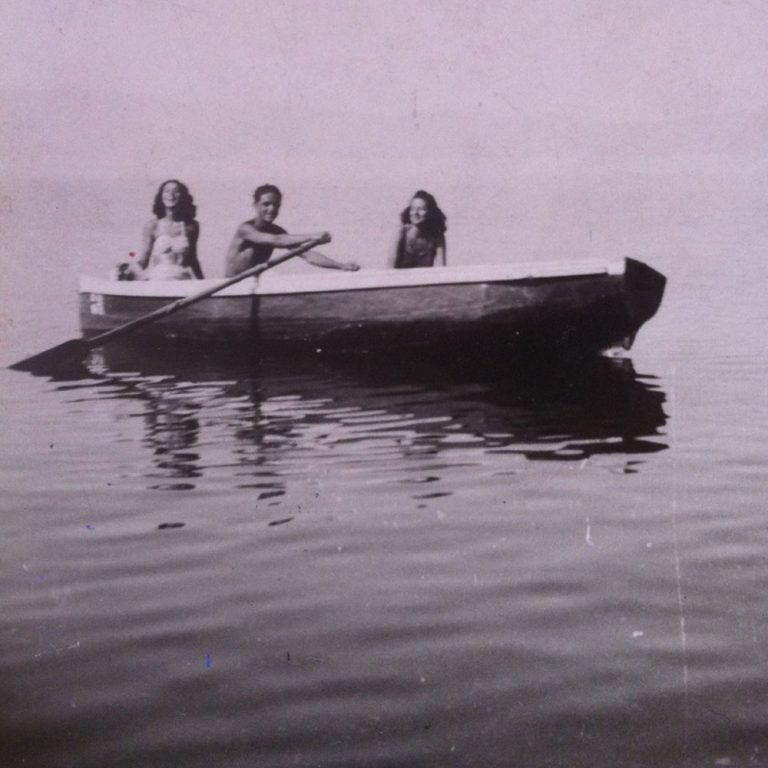

My grandmother (left) with two of her cousins on Lake Ohrid

My mother, an only child, inherited this submerged and submerging compulsion, but with more fear in the mix. Low-grade chronic anxiety, but also sudden black flashes of fear, fear of depths mixed with a yearning for depths. I was, of course, next in line, and the fear kept me very close to my mother. It kept us close, because we couldn’t tell the difference between love and fear. Until it began to drain me of my vitality, later in life. Trust was eroded by fear, and eventually an arid space opened up between us, like the basin of a prehistoric sea.

My mother was born three years after the end of the Second World War in a Sofia ravaged by British and American bombs, with fragile health that needed support and deteriorated in later life. We have been quite literally separated by oceans for years now, but our illnesses have always mirrored each other with ghostly resonance. At the time of this lake journey, I was recovering from a severe health crisis which featured fatigue, widespread pain and a black, waterlogged heaviness in my bones. I was weighed down by an impersonal dread.

In my search for healing, I found Daoism and traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). In Daoist cosmology, everything physical has a metaphysical dimension. Material phenomena, including illness, are merely localised, temporal manifestations of timeless, universal energy, or qi. The ocean of qi precedes and outlives all material reality. In the holographic universe of Daoism, the human body is a microcosm of the earth, with its cycles of death and regeneration. In the Daoist theory of correspondence, the inner and outer worlds reflect each other, and every living ecosystem, including the human body, is based on five elements and their interplay: wood, fire, earth, water and metal. Water is the strongest: it extinguishes fire, corrodes metal, rots wood and flows into the earth. Water always finds a way. Even when it evaporates, it comes back as rain.

In Daoism, the essence of vitality, or jing, with which we are endowed by our parents at birth, is contained in the kidneys. This water organ is the jewel in our inner garden, because jing carries our precious genetic imprint. It is temporally finite. When jing runs out, we die. This is why the decline of kidney meridian energy is associated with ageing in TCM – marked by greying hair or loss of hair, cold extremities, loss of fertility and a general heralding of winter. Beyond the jing, the kidneys’ purifying instincts decide what is health and what is poison, and like a hibernating bear, they store our reserves of life force, to release them in times of crisis. You can use up your jing prematurely and become burnt out.

In the elemental classification, water and the kidney are associated with the emotion of fear, the colour black and the function of conservation, protection, memory, temperance and deep knowledge. People with dominant water qualities in their constitution and personality seek depth, solitude and understanding, including of death and all subterranean mysteries that the other elements can’t face. Water is, in terms of mythos, Plutonic: it is the underworld. Water does not like being breached, and its greatest fear is not death, but extinction through invasion. When out of sorts, water is black ice: hard and unyielding, it says no. It can form stones in soft places, and make things rigid, petrified, stagnant, shut away from the sun. Like the women in my family, when we are in crisis.

The sisters were waiting for me by the boat, smiling, tanned, relaxed. They had a lot of fire in them.

‘I think I reached the deep,’ I said, water dripping from my words. I had swallowed a lot.

They laughed. They mirrored each other – just like my aunts here, who were identical twins and finished each other’s sentences. In fact, my aunts and these two girls were related through marriage. By the lake, everybody was related, and like the lake, everything had a mirror image, a double: nations, official histories, siblings and mother-daughters. My third aunt, their radiant sister Tatjana, had died as a young woman and my grandmother, who was her beloved aunt, had followed a couple of years later. Somewhere between the two world wars, the Cold War and emigration, our family had been fragmented and weakened by hard borders and the hard propaganda that goes with them. But here at the lake, all felt close. The dead and the living alike.

Sign in to Granta.com.