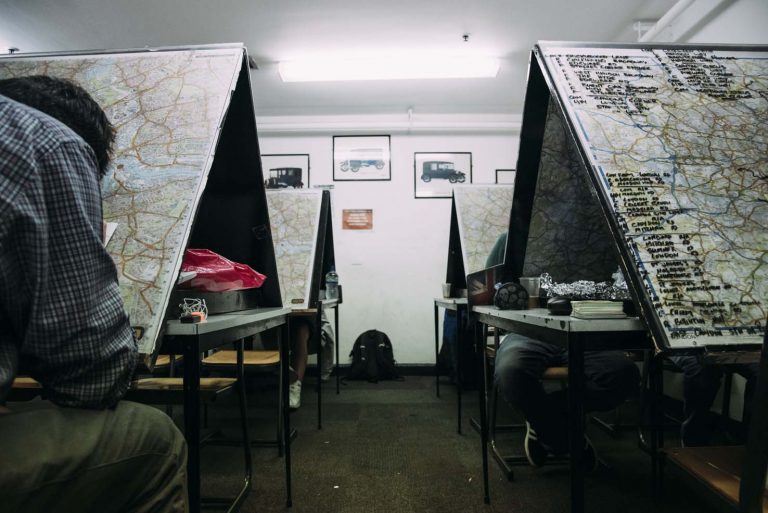

Outside the Knowledge school it was raining, the perennial light drizzle of London. Inside, groups of people huddled around giant A0 maps. The only sound was the squeaking of felt-tipped pens tracing routes along laminated surfaces of the two-dimensional city; the spindly tendrils of London curling their way around us. The atmosphere was monastic; mantras repeated in hallowed tones in a language not meant for the uninitiated.

‘Left Ifield Road, right into Old Brompton Road,’ said Kingsley Russel, his eyes looking into space, brow furrowed with concentration. ‘No, that’s Fulham Road,’ his study partner Rick quickly corrected him. Kingsley, his hair close-cropped, a diamond earring twinkling, shook his head. His eyes rolled back as he tried to reorient himself on the route he’d been calling out. ‘Left Hortensia Road, right Kings Road, left Lots Road, comply roundabout, leave by Chelsea Harbour Drive.’

Kingsley, Rick and the others were attempting, by calling out runs and scribbling lines on maps, to memorise the streets of London; their names, their restrictions (whether or not you can turn right into Old Brompton Road), and any point of interest that a potential passenger might conceivably ask for. Hotels, restaurants, embassies, theatres, cinemas, Tube stations, anything, really, that constitutes the functional city.

The Knowledge, the fabled London taxi exam, amounts to learning the minutiae of over 25,000 streets and over 120,000 points. It takes the average Knowledge boy, as they’re known, four years of intensive study to pass and be awarded the legendary green badge and with it the right to drive a hackney carriage – a black cab.

When I met him, Kingsley, a carpenter by day, had been studying the Knowledge for over three years. He was in his late thirties, and muscular. As he would point to areas on the map his shoulders would heave. On one of his biceps he had a tattoo of a large letter K. He’d recently moved and his entire house, he told me, was covered in notes – road names, restrictions, points – and in his living room he’d built himself a slanted table with the pinewood left over from doing the floors. The map perfectly fit the table. Before, he said, he’d had a sofa cushion and would kneel on the floor, the map spread out beneath him. I can see him in that position, as if in prayer.

Learning the Knowledge takes two forms: map and road. The first – map – is in schools like the Sherbet Knowledge school in Dalston, where the learning is focused on the map and recall, and Knowledge boys and girls pair off to test each other. The second is the physical experience of ‘pointing’ – being out on the streets, typically on a moped, travelling along predetermined routes found in the ‘blue book’. The first of these routes is Manor House to Gibson Square and when called out sounds like this:

Leave on left – Green Lanes

Right – Brownswood Road

Left – Blackstock Road

Forward – Highbury Park

Forward – Highbury Grove

Right – St Paul’s Road

Comply – Highbury Corner

Leave by – Upper Street

Right – Barnsbury Street

Left – Milner Square

Forward – Milner Place

Gibson Square facing

The blue book divides the city into 320 distinct runs. At the end of each run, the student takes a quarter-mile radius and notes down anything within it that could be conceivably called by an examiner. This physical process is integral to learning the Knowledge. It’s estimated that the average Knowledge boy covers at least 20,000 miles while studying for the exam. The Knowledge has a 27 per cent pass rate; lower than that for the Metropolitan Police.

Completing the Knowledge requires not a single test but a series of ‘appearances’ held at the Carriage Office. There are three stages to the appearances, characterised by how far apart from each other they are; students start with appearances at fifty-six days, which is meant to give them plenty of time to flesh out their understanding of the city in-between exams. The next stage has appearances twenty-eight days apart and the final stage is twenty-one. Hopefuls are expected to turn up suited and booted and to defer to examiners politely, calling them Sir or Madam. Poor manners and unpolished shoes can lead to immediate fails.

During an appearance the examiner will ask for four routes, which the examinee must recall immediately from memory there in the room. The examinee is then given a grade for each one. They need at least four Cs to pass to the next stage, but even this is extremely hard. In any given stage, a student can only get three Ds before they fail and have to repeat the stage or drop back to the stage before.

Examiners will play games with students – when Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy in September 2008 there were reports of examiners telling students, ‘Take me from Lehman Brothers to the nearest jobcentre.’ They try to put their examinees off – they’ll whisper, or they’ll shout, or they’ll ignore the candidate altogether. The idea is to simulate the outside world; a cabbie will see the full spectrum of London through their rear-view mirror, and they have to maintain their composure whatever the city decides to throw at them.

Outside the Carriage Office, people from the Knowledge schools wait for examinees and mark down the runs that were called by each examiner. Sheets of these are then sold in the schools and people try to divine, like reading tea leaves, what might be called in the future. ‘I got a point that had never been called before,’ Kingsley told me, ‘it was a place called Satan’s Whiskers; it’s a little bar – grimy looking place on Cambridge Heath Road. It was something she may have thought I couldn’t pull, but I pulled it.’ There was obvious pride in his voice.

It is a dizzying feat of recall that makes London black cabbies renowned the world over; a coterie of navigators so impressive that their brains are scanned by neuroscientists. A team exists in the Department of Experimental Psychology at University College London that analyses people studying the Knowledge; they famously discovered that working towards the Knowledge causes an increase in grey matter volume in the posterior hippocampi and with it a noticeable improvement in their memory. People who have completed the Knowledge are at significantly less risk of developing dementia or Alzheimer’s in later life.

London’s cabs have been regulated since 1637, when King Charles I, bowing to public pressure, proclaimed that there should be a ‘small competent number’ of coaches permitted for the gentry. However, it was only after 1851 when London hosted the Great Exhibition that the foundations for the black cabs that we know today were put in place. That year, hundreds of thousands of visitors from all over the world poured into the city and utterly overwhelmed the cabmen of the day. The inherent structure of London, which is essentially a series of interconnected villages, and the fact that mass tourism was only just starting to emerge as a phenomenon, meant that horse-and-carriage men only knew their own small patch of the city. The confusion that ensued, and the numerous complaints that the newly established Carriage Office received, prompted them to create a test that all carriage men would have to pass should they wish to ply their trade. It was decided that they should have to intimately know the streets of London in a six-mile radius of Charing Cross – as far as a nag could go without food or water.

What the Knowledge represents, in essence, is an attempt to untie the Gordian knot of the least planned city in the world. London has never undergone a Haussmann-esque revamp; the closest attempt to impose a grid system on the city came from above, during the Blitz, and would have only succeeded had the entire city been flattened. Instead, ancient lanes squirrel their way around repurposed bomb craters; squares appear as if at random, streets get bisected and spawn multi-headed on the opposite side of the road. Add to this the ever-changing one-way systems, the cycle superhighways and pedestrianised zones, the Tube and Overground lines, the DLR and, to the south of the city, even a tramline.

The pressures of studying for the Knowledge today are compounded by the fact that few people can understand anymore why someone would do it. It can seem impossible to have any conversation about the Knowledge without having to, in the same breath, talk about Uber. The service has over 3.5 million registered users in London, and is especially popular among millennials. It is easy to pit black cabs against Ubers as if the two were locked in a prize fight. Commentators have pointed out that Uber’s drivers are typically first-generation immigrants, and black cabbies tend to be white working class, from areas like east London. So not only is this conflict a story of tech disruption, it can be read as a fight for the capital’s soul.

But that picture is reductive. It’s too simple to put Uber on one side and the black cab on the other. For one thing, the current crop of Knowledge boys is more diverse than ever before. Kingsley is black British and his family is of Jamaican descent. There are also more women taking the Knowledge, though they are still a minority. Uber is just one challenge of many in a city that is always changing. The legalisation of private-hire minicabs in the late 90s, the rise of Uber and other ride-sharing apps, satnavs, Google Maps, the night Tube, the promotion of cycling and the looming spectre of self-driving cars; all of these have served to undermine the Knowledge. Today the average age of a black cabbie is fifty-two years old. According to Transport for London, only 5 per cent of working taxi drivers are under the age of 35. Despite these threats, Kingsley remains optimistic. ‘I don’t worry about Uber too much,’ he told me, ‘London’s a big city. There’s plenty for all of us.’

‘A lot of people ask me why I don’t just become an Uber driver,’ said Terry, another Knowledge boy I interviewed, ‘but they just don’t get it.’ Unlike most Knowledge boys, Terry had a university degree and a high paying career before, but he had burnt out and decided to pursue the freedom that driving a taxi would afford – ‘I’ve been in an office on a sunny day and felt like, you know what, it would be great to go out today.’

Knowledge schools are full of builders, postmen, bus drivers, plumbers and other vocational labourers who see the black cab as a vehicle for social mobility. Ask them why they subject themselves to the Knowledge and they’ll repeat a similar set of reasons: flexibility, no boss and good pay. When I first met Kingsley I told him that I was doing a PhD. He raised an eyebrow. ‘So, you’re studying three to four years, just like I am,’ he said, ‘but yet at the end of it all you get to put Dr at the start of your name, and what, I’m just a taxi driver? Is that fair?’ I was suddenly aware of how much bigger than me he was. Then he laughed and patted me on the shoulder gently. ‘It’s fine. You can be Dr Barclay. I know how much academics make, and I’d rather have the money.’

Figures are hard to come by, but most agree that even today, with the undercutting of ride-sharing apps and private-hire minicabs, a relatively hard-working cabbie should be making somewhere in the region of £1,000 a week, and the enterprising can make a lot more than that.

Still, this reality doesn’t shake the perception that Knowledge boys aren’t making a sound investment. Terry told me that ten years ago everyone would have known a cabbie. ‘They’d have said, “Well done mate cabbies make a good living don’t they, work four days a week, spend three days a week on the golf course, sounds like a great life.”’ Today, people take more convincing, especially when we all have Google Maps in our pockets.

Most of the arguments that the Knowledge boys offer in response are a little weak. They argue that Ubers pulled over on the side of the road while tapping in addresses cause congestion; that satnavs can fail and that they’re not updated fast enough so they don’t reflect the reality of the ever-changing city. While it’s possible that Google Maps could unexpectedly fail tomorrow and that all the geo-spatial satellites could fall out of the sky it’s unlikely. Waze crowdsources instant updates on the conditions of roads. It even marks dangerous potholes and badly parked vehicles. It’s difficult to see how a single person in possession of the Knowledge could keep up as accurately with all of the happenings across the entire city on any given day.

One day at Sherbet I had parked my bike up outside. I don’t have much of a sense of direction. Despite living in London most of my life and having grown up in the city, I still can’t get around it without a satnav. When I cycle, I have a small pouch on the front of my bike that I can put my phone in so I can use Google Maps. One of the guys noticed me fumbling with it one day and soon I had a group of Knowledge boys all quizzing me on where I was going. ‘Don’t know how to get there do you?’ they laughed.

But I did know where I was going – or at least, with Google Maps installed I knew that I could follow the blue dot and would find the restaurant I was headed to without too much hassle. If I can do what they can do – get from the school in Dalston over to Islington, albeit aided by my phone – then what is the point of the four years of trudging about the city on a moped?

When I open Google Maps I know that I can follow the blue dot and I will arrive at my destination, but this is only one kind of knowing. What the Knowledge provides, through months and years in front of maps and scurrying to-and-fro throughout the city, is another very different kind of knowing.

Perhaps the argument that the Knowledge boys are making is a deeper one, less about the practical differences between using Google Maps versus drawing on recall, and more about knowledge itself. Philosophers make a distinction between declarative and procedural knowledge. The former is knowledge that and the latter is knowledge how. English as a language does not differentiate between types of knowledge very well. In French, to know or understand a fact is savoir, but to be familiar with someone or something through experience is connaitre; in Spanish saber, and conocer; in German wissen and kennen. The Knowledge as a technology for understanding the city is a constant marriage of the savoir of map learning, of seeing Vauxhall south of the river, and the connaisance created by physically traversing the river, feeling the breeze hit your face on your bike as you mount the bridge and then seeing the green behemoth of MI6 before dropping down to the arches.

The way that the internet privileges declarative knowledge turns our brains into library card systems: we know where knowledge is, and how to access it, but the knowledge itself is stored elsewhere, and we tacitly trust its veracity.

In the context of Google Maps, this doesn’t seem so problematic. There are strong commercial incentives for Google to keep their maps up to date. But in the broader context of the internet, there are countless examples of how difficult it is to trust what we are presented with: Russian hackers, bot farms, the opacity of algorithms and AI neural networks, fake news, etc. A litany of tech-based interventions have corroded our capacity for a shared social reality. By embracing the limitless potential of the cloud, we have changed the way we access knowledge, but we haven’t yet developed a strong enough system to help us decide whether what we’re accessing has any real value.

Theoretically, a Knowledge boy can learn the whole map of London by sitting in a Knowledge school and reciting lines; but they’ll all tell you that in reality they need to be out on their bike if they want to really know it. They are intimately feeling it out; dutifully marking down the roadworks, construction sites, engineering projects and the new restaurants and hotels. This is how they can claim to know it. I think that’s what they mean when they tell me that Google Maps might fail. It’s not that the app might one day glitch; it’s that they are making a conscious choice to not rely on some ephemeral source that skuds in the atmosphere – they know there are roadworks today, they saw it with their own eyes.

Perhaps it is analogous to what a medical student goes through. Seeing the Knowledge boys with their maps spread before them is to see them pour over the cardiovascular city; its beating heart and the network of arteries and veins that connect it. The river is carotid; it is around this that everything else is oriented. In much the same way as med students spend inordinate hours with their nose in books writing out flashcards with the names of body parts and viscera and chemical receptors, Knowledge boys trace the map. We’d never trust a surgeon who hadn’t wielded a scalpel – it is to the morgue that med students go to hone their skills, their connaissance of the body, before they finally practice on the living. On their bikes, the Knowledge boys dissect the city, trace its connective tissue and try to unravel its mysteries. Only then can they definitely say they know how to get around the city.

When I described the process of learning the Knowledge, map and road, to Professor Eric T. Meyer of the University of Oxford’s Internet Institute he offered me an analogy from his past. As a child growing up in middle America, he had a teacher who would set his students random offbeat questions that weren’t in any of their textbooks. An example was when he asked the class who was on a $100 bill. This was not the kind of town where these were commonly seen. So, Meyer went to the local bank and asked the manager if he’d open the vault and show him one. Dutifully, he noted down that Benjamin Franklin topped the bill. ‘The point,’ Dr Meyer said, ‘was not who was on the bill, but how we would go about finding out.’

When I ride my bicycle, all I need to know is how to open Google Maps (or Apple maps, or Waze, or Baidu maps in China), type in a postcode and then I know how to get to my destination. At a recent talk that Meyer had attended in Sheffield, a researcher pointed out that a seventeen-year-old, when asked how he knew if something was true or not, responded that as long as it was the first result on Google then it was true. ‘The point is that we know where knowledge is stored – the internet; and we largely know how to access it – Google. But are we able to differentiate it, and evaluate whether it is worth anything?’ Meyer asked.

This is not to say that the Knowledge is a purer or better form of knowing the city. Once Google has put out a free digital map then the economic value of the Knowledge is severely undercut. Why carve the map of London into your hippocampus, or pay for the privilege of riding with someone who has?

The Knowledge is brutal. Appearances break people; pointing is isolating. Norman Patterson, who has been a black cabbie for a few decades, said the Knowledge nearly cost him his marriage. He remembered going on dates and spending the entire meal going over the route to and from the restaurant; walking to the car and jotting down the name of every shop. ‘Sometimes I’d watch old episodes of The Bill or Casualty, just to see how the roads had changed,’ Patterson told me. Terry, keeps a list of the friends that he’s seen. ‘And once I’ve seen them, I tick it off, like “seen them”. And that’s it for a year,’ he said, a twinge in his voice. ‘I imagine the divorce rate is very high for us . . .’ he said, letting his words hang for a few moments. ‘I mean how can you have a girlfriend when you need to be out at night on the bike and when Sunday is your best day to be pointing because the roads are less congested?’

In Plato’s Phaedrus, Socrates worried about the consequences following the development of writing – that committing things to paper and not storing them inside one’s skull would cause people to ‘cease to exercise their memory and become forgetful’. Worse, because knowledge could now be passed without proper instruction and the intense work of memorising it, people would inevitably become ‘filled with the conceit of wisdom instead of real wisdom.’ Every tech advance comes with its critics.

When I was working on this piece, I gave a talk about some of the ideas to a group of anthropologists in China. One of them commented that this example was emblematic of the difference between individualistic Western societies and communitarian societies like China. ‘It is inconceivable to me,’ he said, ‘that you would make a single person learn all of this just to drive a taxi.’

In China, before the advent of Baidu maps (Google is banned in China), taxi drivers would have short wave radios. Two hundred or more would be in a group together and each would know the part of the city where they grew up in or were most familiar with. When someone didn’t know how to get somewhere, he’d radio into the group and the hive mind would respond with how to get there.

This worked especially well in post-Mao China, where economic development was so fast that entire city districts could change completely within a few months. It also created a strong community for the drivers, who would feel intense loyalty to their radio teams. But it came with risks; if you didn’t socialise properly with the group you could be kicked out. Suddenly you’d find yourself painfully alone in the city, without being able to know where to go.

There are pros and cons to all our ways of knowing. The internet is untrustworthy; your short wave radio team might turn on you; the Knowledge might break you. But these ways of knowing aren’t exclusive; progress doesn’t have to come at the expense of one over the other. It is possible to use Google Maps every day, like I do, and to still see the value in the kind of knowing that defines the Knowledge.

The Sherbet school is named after the cockney rhyming slang for riding a cab (sherbet dab/riding a cab). It is the brainchild of Asher Moses. Moses got into the taxi leasing business in the early 1990s, ending up with a fleet of over 200 taxis. He built his fortune turning these cabs into a highly efficient flotilla of mobile adverts. It’s a misnomer to call the fleet of cabs in the backlot at Sherbet black cabs; they span the entire rainbow – some are bright pink, emblazoned with adverts for Sure, a women’s deodorant. Others are entirely yellow, decked out with adverts for a travel group.

Moses has long partnered with charities and tourist boards. He introduced ‘ambassador drivers’ who have knowledge about the product they are advertising, which means that if his client were the Texas tourist board, he’d send the driver to Texas on an orientation trip to get a feel for it. When someone says, ‘terrible weather,’ the driver might respond, ‘just got back from Texas, great weather . . . stayed here, stayed there, did this, did that.’ As Moses noted, it is a great way to open conversations. At one point, his biggest client was the Visit USA Association. ‘We had fifty taxis covered in the Stars and Stripes,’ he told me, pride underlining every word, ‘I sent a driver to each state.’

Moses has recently reinvested millions of pounds into the taxi industry, growing Sherbet to a fleet of over 660 vehicles, many of which are electric, all fitted with credit card machines and telematics which allows him to track his fleet and operate his business more efficiently – he says the business is generating in the region of £17 million a year. ‘If taxis had lost, I wouldn’t be investing in them,’ he said plainly.

For Moses what is killing the black cab isn’t the onslaught of Uber and private hire, it’s that the industry lacks efficiency. ‘When people came back from the north on a Sunday in the evening, and the stations are packed and heaving, how many of my taxis are working?’ he asked me, answering before I could respond that that the telematics he had installed gave him the answer – 12 per cent. He also noted that taxis used to be used for small jobs in the city, the £5–10 jobs, and were never really intended for the long-haul journeys to the suburbs for which Uber is significantly cheaper. ‘If we were there when the customers were there, then we’d be laughing,’ he argued.

In September 2017, it seemed as if the Knowledge might have been saved, at least from its most obvious threat. Transport for London (TfL) announced that it was revoking Uber’s license in the city after mass allegations of sexual assault by drivers, and the fact that Uber’s managers had done nothing in response. The mood in the Knowledge schools was jubilant but short-lived. Uber has kept operating. The response among the public was decidedly mixed; those in difficult-to-reach pockets of the city wondered aloud how they’d be expected to get home late at night; others claimed this was an example of a socialist London Mayor trying to undercut the free market; women came forward to argue they felt safer in Ubers where they could get the information of the driver direct to their phone, (despite the fact that TfL data shows that in 2016, 31 Uber drivers were charged with 34 sexual offences in London, while in the same period there were no offences by black cab drivers).

The mayor wavered, reinstated Uber’s license, then in November 2019, TfL once again revoked the license due to lack of safety. As of writing, Uber is appealing the decision. Uber is shedding money globally. In the US Lyft, its biggest competitor, now takes more customers daily. In China, Uber was eaten whole by domestic rival Didi Chuxing after bleeding billions of dollars competing for the world’s largest ride-sharing market. Uber founder Travis Kalanick was ousted in 2017 because of his complicity in creating a toxic work culture at the company. Maybe Uber won’t be around in a few years; but the industry it helped foster is here to stay. Every time I come back to London from China there seems to be a new ride sharing app; Bolt, Ola, Kapten, ViaVan. There are always new ways to get around the city.

Can the Knowledge survive? For all its tortured beauty, the Knowledge is suffering at the hands of its own inherent paradox. What distinguishes London’s black cabbies and makes them rightfully the pride of London is the maddening exam which is also threatening to make them extinct. In 2015 the Conservative Greater London Authority (GLA) published a report on the state of the black cab entitled Saving an Icon, which suggested scrapping the Knowledge for a simpler test – ‘in New York the examination process lasts 80 hours, which can be completed in two weeks by astute students’ the report states, ignoring that New York is a grid system.

Where the GLA sees shackles holding the profession back, the cabbies themselves see a gold standard that sets them apart. The Knowledge is far more than a professional qualification; it is the existential raison d’être that defines them. Black cabs without the Knowledge are just vehicles with good turning circles, goes the argument.

But that argument is circular. The Knowledge anchors the black cab in time and makes it the icon it is, but like any good anchor it also firmly circumscribes the range of movement available to compete in a digital marketplace. The issue of self-driving cars, looming on the horizon, complicates this even further.

One day, after a few months of not hearing from him, I sent Kingsley a text and asked how he was getting along. I asked if I could take a photo of his living room; the pinewood table and the sticky notes on every surface. He responded that they were all gone – his final appearance was the next day.

He passed. He called his first run a little wide, but then he pulled it back in the following three. ‘And that Sir,’ the examiner said, ‘that there means today you have finished.’

A few days later Kingsley picked me up at Manor House in the brand-new cab he was leasing and we drove along the first run in the blue book. We passed Castle Climbing Centre, an odd crenellated building that looms large from the street. In twenty-seven years in the city I’d never seen it before. We travelled along Brownswood Road; up to Highbury park where the old Arsenal stadium had been converted into flats. Kingsley pointed out the Hen and Chicken bar, which is a favourite of examiners, who like to call it in the same breath as the Egg nightclub (it’s unclear which comes first). Kingsley pointed out the Union Chapel and cut into Milner Square which lead us finally to Gibson Square. The whole route was a little over three miles.

When we arrived, we chatted a bit about the future. ‘Maybe, once I’m comfortable with this I’ll train to be a chef,’ he said, showing me plans he had for a new kitchen he was building in his house. Other Knowledge boys I know had also gone on to study other things. Many qualified taxi drivers go on to take the Blue Badge exam to become accredited tour guides considering they already know so much about the city.

The Knowledge is a reflection of the Enlightenment ideal of learning as an end in itself – by following the map the Knowledge Boys undertake a journey that changes them. For some, this is just the beginning. Google Maps is frictionless, a flat plane of blue dots that saves us from ever getting lost. But what of the cliché that you have to be lost to be found? Perhaps that is the fatal flaw of digital convenience; all destinations, but no journey.

‘I don’t know,’ Kingsley said, pausing for a moment, ‘this is a good job, this is. Like today, I’m taking you around and it doesn’t matter. My time is mine. I can go earn money later.’ I noticed that he’d added to the tattoo on his arm, so the large letter K no longer stood alone; it now reads Knowledge is Power.

He had also started teaching at a friend’s Knowledge School that runs out of a rec centre near Elephant & Castle. They assemble in a massive hall; Kingsley calls students to sit directly before him, a large A0 map propped on a chair separating them, the cardiovascular city not visible to the student. They call routes and he dutifully draws the line. Then he calls them over, a string of best fit laid between the points, and shows them where they’ve gone wrong.

‘What I’ve learnt about London is that it’s a small place,’ he told me. ‘I didn’t know that before the Knowledge. So, let’s say something like Leveridge Road, or Stamford Hill, it seemed far from where I lived in Camberwell – it’s literally just up the road. When you know where you’re going, nowhere is far.’