We drove too fast on a dark road; there was no other traffic. Everything had been going too fast from the moment of arrival at Panama’s airport. A bent bony little man seized my luggage and ran with it, shouting, ‘Hurry, Señora, I have no salary, I live on tips!’ Immigration and customs were only a pause. The porter dumped my stuff on the pavement. A taxi driver shouted, ‘Come, Señora, with three it costs only eight dollars to the centre!’ I was hustled into his car where two passengers waited. I thought all this rush and noise were hysterical. What was the matter with these people?

The young Costa Rican sitting next to me said he was going by bus tomorrow to buy merchandise in the Free Zone at Colón, at the Caribbean end of the Canal, and if God wills would be back in Costa Rica the next day.

The middle-aged Panamanian in the front seat said, ‘Noriega used to run the Free Zone. Now it’s a nephew of Endara.’ They all laughed. Endara is the new President of Panama, installed by the US Invasion.

Then the panic talk started. I heard a variation of it every day from everyone I met.

‘This is a very dangerous place,’ said the Costa Rican. ‘I do not like to come here. There are robbers everywhere. They have weapons. If you do not give them what they want, they kill you. You should not be travelling alone.’

The Panamanian passenger said, ‘Never be out after nine o’clock.’ It was now nearly half past nine. ‘Do not walk on the streets alone. If you take money, take only what you need and hold your purse close to your side.’

The taxi driver asked: ‘Which is your hotel?’

I said any hotel in the centre would do.

They discussed this and the driver said, ‘I will take you to the Ejecutivo; it is clean and comfortable and safe.’ Seguro was the operative word.

We turned off the wide street by a lighted petrol station. High board fences lined both sides of a narrow street. ‘Those stores were looted,’ said the front-seat passenger. ‘Everyone stole – not only the poor, the rich too.’ We stopped in the dark and waited until the Panamanian had opened his front door and gone inside. They dropped me at the Ejecutivo with renewed serious warnings to take much care.

At ten o’clock, I stood on the first-floor balcony of my very clean, very comfortable, safe room and looked at a dead city. No movement, no sound, no lights. The curfew was at midnight. Panama had been famous for its nightlife, a wide-open town. This was almost three months after the Invasion.

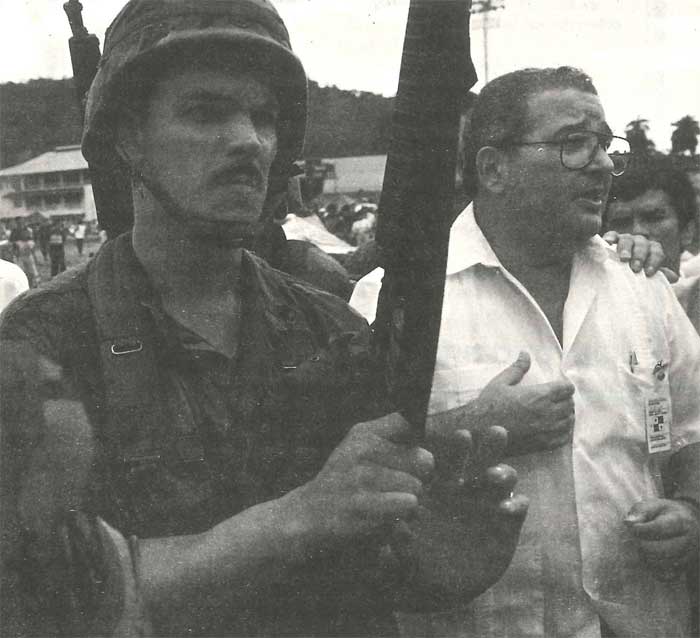

Panamanian President Guillermo Endara (right) with American troops

I had to change traveller’s cheques, and my delightful hotel nestled among banks and closed nightclubs. The banks have a Pharaoh complex; there are 140 of them. They are towers or palaces, monuments to money. A mirrored skyscraper, with swiss bank in red neon on top, gleamed nearby. Why not be brave and walk? The streets in this part of town were wide and clean, every building opulent, white, with decorative planting. No one was walking.

When I reached the air-conditioned bank foyer I was drenched in sweat, a sensible reason for not walking. To my surprise the Swiss Bank used only a few floors in the middle of the tower. To my greater surprise I found myself in a small, linoleum-floored hall, with a wood shelf and a man behind a dirty glass teller’s window. No, they didn’t do retail business; this was an international bank, engaged in shipping money around the world. He said that the Invasion had closed the commercial banks for a few days. But 24,000 armed men, attack helicopters, tanks and riotous disorder in the city had not interfered for an hour with international banking.

The commercial bank, very grand, had an armed private guard in front of its locked, iron-grille door. The teller gave me a wad of used dollar bills. Money in Panama is American. Due to two years of the US embargo, supplies of new dollar bills ceased. Paper which has changed hands for all this time is so worn and foul that it feels like oncoming skin disease. Now, stiff with cash, I hailed a taxi though the bank was only a few long, hot blocks from my hotel. The taxis are little beat-up cars, like fast water-beetles, with room for three passengers; they collect trade as they go. The fare is a dollar for any distance. You flag one down and if it is headed in your direction, you hop in with the others. This taxi driver said, ‘Be very careful. Many taxi drivers have been robbed and killed. It is worse than war here.’

I put my fortune in the hotel safe and set out to improve my looks. There was a beauty salon on the side street by the hotel. While her assistant washed my hair, the jolly, blowsy hairdresser said, ‘People stole anything, from viciousness not need. Twenty-five beauty salons were robbed of everything, even the washbasins. Noriega stole and he taught the people to steal. There was such corruption here; it was a sickness. They left this street alone except for the jewellery shop. Where I live was not harmed. Only the houses of the poor were destroyed.’

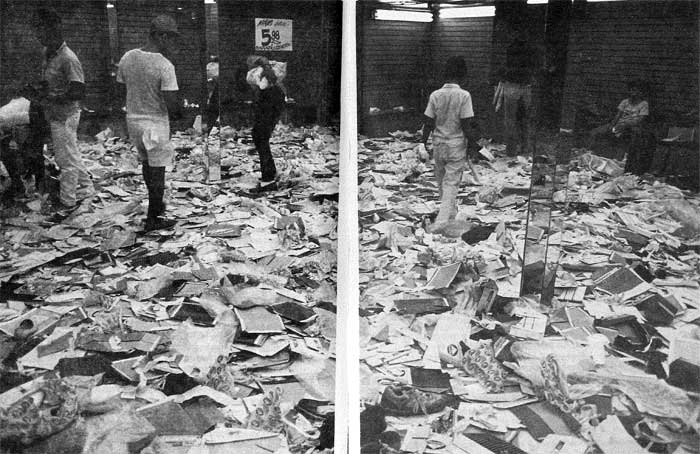

I was slow to understand the catastrophe of looting that ravaged the whole of Panama City for three days, beginning the day after the US night Invasion on 20 December. The structure of the state was wiped out in the six hours of the main attack. US Southern Command, the permanent military establishment in Panama, had created a vacuum in civil order, but did not recognize that it was obligated to patrol and protect the city. The troops had no orders to do so. The people turned into mad locusts, swarming through the streets. At the time it must have seemed like the biggest wildest happiest drunken binge ever known, courtesy of the US Army. The hangover is painful; Panama has not yet recovered. ‘I saw American soldiers sitting in a tank, watching,’ said the hairdresser.

I asked about the US embargo, which starved Nicaragua and has been a crippling burden on Cuba for thirty years. In Panama, it was meant to cause hardship and popular discontent that would drive out Noriega. She shrugged. ‘There was always plenty to eat in Panama. We lacked for nothing.’ In fact, the embargo reduced Panama’s gross national product by 20 per cent, but hurt mainly the rich, the white business community, since the United States is Panama’s major trading partner.

As I needed to buy a plane ticket and there was a travel agency a few doors away, I took my problem to a stylishly dressed, thirty-something businesswoman, who reserved a ticket quickly on her computer. She said, ‘The United States created that monster; they knew Noriega well. They even decorated him. He has been in power here for twenty-one years.’

I asked what it was like to live here in those years.

‘Nothing happened to people like me under Noriega. If you were neutral it was all right. Mostly the poor favoured Noriega.’

Her facts were not entirely correct. Panama had indeed been a military dictatorship for twenty-one years, which did not disturb the US government until two years ago. Noriega was the intelligence chief of General Torrijos, the previous military overlord. Noriega had been top man for six years, behind a president and legislature and elections, the way the United States likes things to look. But it is correct that American governments knew Noriega well during three decades. Noriega did not suddenly become a drug-dealing fiend in the last two years, after a blameless life. President Carter took him off the CIA payroll; President Reagan put him back.

I asked about the banks: why build those immense, unneeded towers?

‘They rented out their extra space for offices,’ she said. ‘There will be many empty offices now. You know this city was called “the washing machine”. Anybody could open an office and be a banker and launder money, no questions asked.’ The cowboy bankers may be gone but the useful secrecy laws remain.

The heat was heavy, a weight on your body, and the sun was blinding. I said I must buy sunglasses and shirts; I would be changing them four times a day. ‘Shop around here, on Via España. Do not go downtown. Above all don’t go near Central. They will see you’re a foreigner: you will be robbed immediately.’ Central is the main popular shopping street in Chorrillo, the district that took the worst blast of the Invasion.

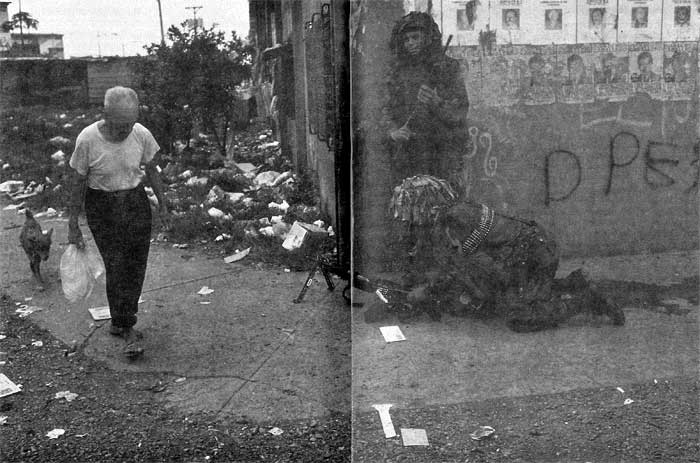

There were three giant round-ups while I was in Panama. Before dawn, 500 to 700 American soldiers and the new Panamanian paramilitary police blocked off poor sections of the city with tanks and made house-to-house searches. The first, most publicized round-up netted 726 ‘anti-socials’, largely illegal Colombian immigrants, forty-six revolvers and a minor supply of drugs, average for private use. The triumphant catch was a tall, skinny twenty-year-old black, nicknamed Half Moon, a gang leader ‘accused of four assassinations’. The papers carried no further mention of anti-socials in later round-ups and no reports of mugging, armed robbery, not even pickpockets. It was finally admitted that there was no great hidden arms cache in the city, nor any sizeable quantity of drugs. Without reason, the people are certain that Panama is overrun by cut-throat criminals, and the panic talk never stops. I think this pervasive fear was shell shock from the terror of the Invasion, something like an unconscious mass nervous breakdown.

The traffic of the capital city, which is called simply Panama, hurtles at race-track speed along the streets. There are no traffic lights. They were knocked out two years ago in a general strike, to disrupt the city. They were not replaced but Noriega had tough traffic cops, armed with .45s, and drivers dreaded fines or prison sentences. In my first days there were no traffic cops. Then a few began to appear with Day-Glo gloves and vests. These uncertain men, all blacks, belong to the new Panamanian paramilitary police. US Southern Command vetted Noriega’s former soldiers on a scale ranging from black (downright bad) to grey (neutral) to white (harmless). It selected a chosen number and gave them a new name. They are no longer the Defence Force; they are the Public Force and their barracks now bear the words Policia Nacional. They have also been given a new humiliating uniform, a loose, belted khaki shirt, baggy khaki trousers and floppy khaki hat, like a sun hat.

The people, who find this laughable, are told that this force with new commanders and new orders to be polite and helpful, are new men. But wherever authority must be imposing, there are six-foot-tall, white American soldiers, with M-16 rifles, and those somehow ominous boots and camouflage uniforms, and nobody doubts for a minute who is in charge here: US Southern Command.

My watch-strap broke; I went in search of a watch shop. Advised and directed by people on the street, I found a hole-in-the-wall store, looted clean of its stock, including watch-straps. This small businessman was bankrupt. Insurance, if he had any, does not cover acts of war. The city-wide vandalism was the sequel to an act of war. A slim, neatly dressed young man, chatting with the unemployed proprietor, offered to take me to Central on a bus to buy a strap.

The buses, like the taxis, belong to their drivers and are a treat. They have girls’ names and fanciful decorations painted on their sides: a puffing steam locomotive, a sylvan scene, a luscious blonde on the rear end. When you want to get off you shout ‘parada’, stop, pay fifteen cents and jump down. Juan, my new friend, and I got off at the lower end of Via España, a street more or less comparable to Regent Street. Opposite was the Archaeological Museum and a big Chase Manhattan Bank, both looted. Juan felt awful about the museum. ‘It is our history,’ he said. ‘Now it is gone.’

Central begins here and it looked a mess, litter, garbage, but it is a genuine Panamanian street that still has the charm of liveliness. Every building had been looted and, though some had reopened and some like McDonald’s were operating behind boards instead of window-glass, many remained empty and ruined. The effect was of a recently bombed city. Juan pointed to an untouched shop, offering Oriental wares. ‘The owners are Pakistanis; they protected their place with guns.’ We found a watch-strap.

Juan insisted on taking me to his flat in Chorrillo. We walked down narrow slum streets, stepping around garbage. The houses here were big, old, unpainted wood boxes, four storeys high, filthy, packed with people, the balconies draped in drying laundry. I heard that these structures were built in the early years of the century as boarding houses for the men who dug the Canal. Chorrillo is the poorest and most densely populated district of a long strung-out city where 600,000 people live. At this end, the poverty is stunning; at the other end, wealth is flaunted.

Juan, an accountant, lives on the twelfth floor of a tower-block, one of several rising above the ancient grey wood warrens. The entry was dark and miserable, but once out on the open walkway that led to the flats, you saw how proudly these people took care of their homes. Juan’s spotless, cramped flat was blissfully cool, wind blowing through from the back door to the front balcony. It has beautiful views: behind to green Ancon Hill, HQ for Southern Command; in front to the Pacific and the beginning of the Canal. Juan shares the meagre space with his wife and three infant sons, the fourth well on the way. Here his family, and everyone else in the building, was wakened shortly after midnight on 20 December by the inconceivable noise of bombardment.

‘We all ran to the basement,’ Juan said. ‘We lay on the floor for six hours. We were terrified. The children have traumas.’ (Trauma, misused, has now entered the Spanish language in Panama.) When the noise died down they went back to their flats. A machine-gun bullet slashed across one wall of Juan’s balcony; the windows were broken. For three days this area was without electricity, for five days without water.

Almost opposite Juan’s building, three streets away, Noriega had established his main Cuartel, a compound of headquarters and barracks, set in the midst of the slums. Perhaps Noriega felt most comfortable here because this is what he came from, an illegitimate abandoned slum kid. That Cuartel was the focus for the US Invasion. Noriega was not there and never had been. But the poor were sleeping in their overcrowded tenements all around, and there they died, unless they managed to escape. Juan took photos from his balcony right after the attack. It looked the way any city looks, subjected to modern warfare; like a wilderness of jagged teeth. Juan was most impressed by his photos of crumpled burned private cars.

‘What did that?’ he asked.

‘I’d guess machine-gun fire from helicopters.’

‘Do you see the bodies inside?’

American army engineers bulldozed the area, as much as they could, and now it is a grey stony wasteland, about six city blocks in size. Apparently to shift the blame for the death and destruction in Chorrillo, the story was put about that it was the work of Noriega’s Dignity Brigade, his special thug bodyguard. While pinned down in the Cuartel by helicopter gunships, rockets, tanks and US infantry, men of the Dignity Brigade are supposed to have crept out and set fire to the surrounding slums.

The magazine Army, in its account of Operation Just Cause, prints a photo of a sky-high black cloud which it describes as a fire in a Cuartel building, ‘the result of heavy damage inflicted by air support and Sheridan light tanks’. The Cuartel buildings were cement and would not have burned like that, but the dry old wood tenements burned to the ground. Again as reported by Army, some of Noriega’s troops escaped from the Cuartel and sniped at American soldiers from the upper floors of the tenements. Since when are snipers silenced by erasing whole city blocks crammed with civilians?

After the Invasion, we read in our newspapers first that there were 300, then later 600 dead in Panama. The consensus on the streets of Panama is 7,000 dead. Chorrillo was a death trap. There was also heavy fighting in San Miguelito, north-east of the airport where another Noriega Cuartel is encircled by slums. ‘You cannot see that,’ I was told. ‘They have their Cuartel there now.’ ‘They’ are always Americans. ‘It is closed off by barbed wire. But you could smell the dead, a horrible smell, two days later.’ Juan also spoke of smelling the dead in Chorrillo, three days after the Invasion. It is a smell you know at once though you never knew it before; and you never forget it.

You are not allowed to see San Miguelito, but any taxi driver will take you to the Garden of Peace, a large, private cemetery near there. The cemetery is an expanse of perfectly tended lawn with identical small, flat marble gravestones. A trench of chocolate-coloured earth runs across the rear width of the cemetery. A mass grave. This mass grave is common knowledge. Rumour says there is another mass grave at Fort Amador, now occupied by US Southern Command. Rumour says that there are several more.

In early January, a group of well-known Americans – lawyers, clergy, civil rights activists, students, trade union leaders – formed the Independent Commission of Inquiry on the US Invasion of Panama. Ramsey Clark, former US attorney general, the Commission’s principal spokesman, made several trips to Panama. On 25 January, the Commission sent out a press release: ‘Having spoken to hospital personnel, cemetery and morgue workers and others with first-hand accounts, we believe that as many as 4,000 to 7,000 people may have been killed during the Invasion.’ No one knows the number of the wounded – hundreds? thousands? – and they are unseen. The Panamanian authorities admit that 15,000 families were made homeless, in one night.

I went out to dinner once, hoping for a good meal, but it was too spooky, only five other people in the restaurant and nerves about finding a taxi to get back to the hotel by nine o’clock. The empty streets suggested that everyone had nine o’clock nerves. At night I read the Panama papers. The news was mostly bland waffle. Every day, the ‘fast’ of President Endara made the front pages. In these chaotic times, the President had withdrawn to the Cathedral, where he ‘fasted’, ‘out of compassion for the humble people who are suffering hunger’ and to gain ‘a more spiritual outlook’.

The humble people jeered. They said that the President was a fat man of fifty-three dieting to lose weight for his June wedding to Ana Mae, aged twenty-four. In a brilliantly lit side chapel, whose altar was adorned with a truly hideous plaster statue of the dead Christ in Mary’s arms and big vases of artificial flowers, President Endara received diplomats and delegations and starved on mustard-coloured varnished wood pews. He slept there on a cot. The Presidential piety was much appreciated by the Church. The President fasted for thirteen days, lost seventeen pounds and returned to his offices in the presidential palace, a handsome white building that faces the sea. Here a small group of protesters, bearing handprinted placards, camps silently on the cobbles across from the guarded entrance. One placard stated: ‘No one talks of fasting who knows hunger.’ Another announced: ‘Noriega robbed us, Endara locks us up’.

Everyone asks where you come from. I said Inglaterra which is true. Now I intended to present myself as a ‘periodista inglesa’, an English journalist, at the Casa de Periodistas, the modest compound of meeting rooms, courtyard, tatty bar and union offices of Panamanian journalists. I wanted people to talk to me, and I refused to take any responsibility for the Invasion.

The Casa de Periodistas buzzed with arguing, sloppily dressed men; journalism cannot be a road to riches here. The first protest demo, called by the National Council of Workers’ Organizations, was due that afternoon outside Parliament. I had been gripped by the human misery and the wreckage of the Invasion; I had no idea of its political effect until I met the press.

Upstairs in the union office, a man said, ‘American troops went to people’s homes; they arrested all union officials within three days. They took them to Clayton [Fort Clayton, the main US Southern Command base] for interrogation. They took our pictures. I was held for three days. Some colleagues for weeks, some we still don’t know about. US soldiers moved in here and occupied the place. They only gave it back on 18 January [nearly a month after the Invasion]. About 150 journalists in the private and public sector have been sacked. Not Noriegistans, by God, but anti-gringo. I expect to be picked up any day.’

‘There are American advisors in every department of the government, telling Endara’s people what to do,’ another journalist said. ‘It is against the Panamanian Constitution to have foreigners in our government.’

An angry man said, ‘They sacked 2,000 civil servants, including all the union officials, without any kind of legality. There are 30,000 more unemployed since the Invasion. The worst is that the real hacks, people who took part in the corruption of the Noriega regime, are now part of this new government and saying who should be fired, protecting their own people. If you are against the Invasion, they say you are Noriegista. Soon they will say we are Communists. We are nationalists.’

This journalist spoke with bitterness. ‘Radio Nacional stayed on the air after the Invasion, telling people what was happening. A day later, a helicopter circled their building three times until it got into position, then it fired a rocket into the seventh floor. That took care of Radio Nacional. Then they arrested its director Ruben Dario. The newspaper La Republica came out with reports of the dead, after the Invasion. The next day American soldiers went in and smashed up the offices and closed the paper. They kept Calvo, the editor, in Fort Clayton for about six weeks; now he’s in the Model Prison. We haven’t heard of any charge against him. Southern Command closed two other newspapers and they’ve taken over TV channels 2 and 4 [Panama channels]. To move freely in our own country we need a press card from Southern Command. We haven’t the right to know how many people died because General Cisneros [of Southern Command] took the list. Information is the property of Southern Command, not the Panamanian press. This isn’t a democracy; it’s a US military dictatorship, instead of a Noriega dictatorship.’

‘Noriega is nothing, an excuse,’ an older journalist said. ‘They can’t even bring him to trial. First they said March; now they say January 1991. They’ll hide him away and in five years he’ll be free to enjoy his millions. This Invasion is about the Canal Treaty. The United States has put in a docile government, the oligarchy, the same class we had in 1968. It has the same interests as the United States. There must be an election in 1994, according to the constitution – though we should have an election now to get a legitimate government – and then again an election in 1997 when the Canal is due to revert to Panama. But the United States will make sure there is still a docile government here. That government can abrogate the treaty, say it’s too difficult for us little people to manage, please stay. The Canal isn’t the important thing; it’s the Canal Zone, the bases, the airfields. The United States dominates all Central America now and geographically Panama is the ideal control point.’

The Canal Zone is a strip of land north of Panama City ten miles wide by fifty miles long, between the Pacific and the Caribbean. It contains the Canal, the extensive civilian administration of the Canal, and a major US military installation, plus all their dependants and recreational facilities. By the terms of the 1977 Panama Canal treaty, this will be ceded back to Panama in 1999 and the treaty forbids the presence of foreign troops on Panamanian soil.

The Invasion was obviously long-planned, waiting for a ‘Just Cause’, and Noriega, crazy with hubris, obliged. President Carter had forced through the Panama Canal Treaty; it had never suited the military or the Republicans and no doubt they would like to cancel it if they can. Still, nothing explains the preposterous size of the Invasion, the most copious display of force since Vietnam. Unless Operation Just Cause was intended as a very special PR job: to remind every country from the Caribbean basin to the Strait of Magellan that the United States is the last superpower.

My Panamanian journalist colleagues also gave me a sheaf of documents, press releases from various unions and the American Independent Commission of Inquiry on the US Invasion of Panama. The unions accuse the Endara government of denying their rights, won during twenty-one years of dictatorship. The Independent Commission accuses the US government of ‘police state tactics’, citing cases. The arrest by American soldiers of Dr Romulo Escobar Betancourt, chief negotiator of the Panama Canal Treaty, formerly Chancellor of Panama University and delegate to the UN, who was held incommunicado for five days at Fort Clayton, then turned over to the Panamanian police. The ongoing searches, harassments and interrogation of Panamanian civilians by US military. The arrest order for seventy-four prominent Panamanians, known as lifelong supporters of Panamanian independence, to be charged with ‘impeding the renewal of the Powers of the State.’ The penalty is five to twenty years in prison and prohibition from holding public office. The Independent Commission concludes that there is ‘a clear and continuing effort by the United States government to intimidate and crush any democratic opposition.’

The Spanish word for totally destitute is damnificado. The people who ran from their burning collapsing houses in Chorrillo, with the clothes on their backs, saving their lives and nothing else, were los damnificados de Chorrillo. I wanted to hear their stories, exactly what happened on the night of the Invasion and what was happening to them now. The Panamanian journalists said they were not allowed to see them; maybe I could get in.

Three thousand damnificados are housed at an unused US airfield. The US army built windowless plywood cubicles for most of them in an unused hangar. The cubicles are three metres by three metres. The high, shadowed building is at least cool; the overflow suffocates in army tents. Another 500 damnificados camp in two city schools.

I got to the hangar entrance and was stopped. As I had no press credentials of any kind, I made a bullying scene, saying that if I could not speak to these refugees the authorities must have something to hide. The camp director, from the Panamanian Red Cross, conceded that he would let me in if the ‘Señora’, the government representative, gave me a letter. I returned to Panama. After infuriating telephone calls, trying to find this lady, she appeared at my hotel, a nice oligarchy aristocrat. She wrote a note and telephoned the Red Cross director to expect me.

I went back. This time I got no farther than the guard post. The camp director came to meet me, all welcoming smiles, and took the note. But the American lieutenant on duty, eight feet tall, white, swathed in bandoliers, hefting his M-16 (a seriously threatening weapon) said, No. I did not have a ‘seal’ (a press card from Southern Command?); my name was not on his roster.

I observed that the Panamanian authority and the camp director gave me permission to talk to Panamanian citizens and I did not see what the US Army had to do with it.

‘Anybody can write a letter,’ said the lieutenant, holding the note. ‘I have my orders.’ The camp director, who of course knew the handwriting and knew his superior had agreed to my visit, stood beside the lieutenant, looking at the ground. It was a public humiliation, delivered with indifference. US Southern Command rules, OK.

I said to the camp director, in Spanish, ‘You live under an army of occupation.’

He closed his eyes for a second and said softly, ‘What can we do?’

I said, ‘You have my full sympathy.’

He said, ‘Thank you, Señora,’ and we shook hands.

I walked back to the warehouses where traffic was stopped and found a taxi that had just deposited a passenger, which spared me the long, hot trudge to the main road and a bus. A very young woman, very pregnant, asked for a lift to town. We sat in the back with her five-year-old son between us. The boy was much too thin, pale, dressed in a clean, pressed white shirt and cotton trousers. By chance, I learned from this tired, helpless girl what I had wanted to know. Her story was brief.

‘I grabbed the child and we ran through the bullets. We ran and ran until we came to the sea. Now something is bad with baby,’ she touched her stomach. ‘I must go to the hospital every day. My father gives me two dollars for the taxis. He is a taxi driver. I have no money or anything. Many people were burned up, many, many, old ones and children who could not get out. At the camp they give us coffee and dry bread for breakfast and at five in the afternoon one plate of food.’ She sighed and looked at the boy. He sat on the edge of the seat, rigid and silent. ‘He is very nervous. If there is the smallest noise, he trembles and cries.’

She had been there in one of those big wood boxes when suddenly her home, her neighbourhood, blazed with fire, and the people tried to escape ‘through the bullets’. Her testimony was the reason why Southern Command prevented journalists from meeting the damnificados. She cannot have been a special case. All the uprooted survivors of Chorrillo lived through the same fearful night.

We dropped her at the hospital. I wished her luck, wondering what that might be. Not to die in childbirth? Not to produce a deformed or deranged baby?

I went to my room, showered, and drank duty-free whisky, raging against the Divine Right of US Presidents to do anything they like to poor people in Central America. This arrogance derives from the Monroe Doctrine of 1823, which is no more than a presidential fiat warning the European powers not to meddle in the Americas. The United States would then refrain from meddling in Europe. Ever since, US presidents have meddled ceaselessly in the affairs of sovereign states, south of the US border.

South American states, though tightly entangled in debt to North America, are by now very prickly. After the CIA orchestration of the demise of President Allende of Chile, US presidents are not apt to interfere flagrantly in South America. But Central America could be described as a free fire zone. Anything goes.

Why have the leaders, the media, the citizens of the Great Western Democracies cared long and ardently for the people of Central Europe, but cared nothing for the people of Central America? Between 27 and 28 million people live in the seven states of Central America. Most of them are bone poor, and most of them do not have white skin. Their lives and their deaths have not touched the conscience of the world. I can testify that it was far better and safer to be a peasant in Communist Poland than it is to be a peasant in capitalist El Salvador.

US presidents, who formulate US foreign policy, never worried about social justice in Central America. The White House tolerates any Central American government if it is loyal to the ideology of capitalism and knows its place, subservience to the national interests of the United States as defined in Washington. Washington likes dictators because they are easier to deal with. US presidents regularly clamp down on popular rebellions. The demand of cruelly deprived people for a decent life is seen as dangerous to US interests; quite simply, the poor are dangerous. They are capable of saying: Yank Go Home.

No US president ever deposed a dictatorship in Central America or South America either. On the contrary. Noriega is unique. Noriega would still be there if he had not fancied he could be an independent dictator; the fool got above himself. The drug business will continue; North Americans want drugs; drug money will be laundered discreetly. But everything is in order now; the US has taken over Panama in its usual style, with a friendly native government. ‘Democracy’, which has the sound of silver bells in Central Europe, is a mean joke in Central America.

On the western arm of the Bay of Panama, a forest of condominium skyscrapers rises from untended land. No trees, bushes, flowers, just these massive vulgar buildings. Nearby, luxurious houses are screened by large delightful gardens. This neighbourhood is the golden ghetto of Paitilla, the habitat of the class that the people call la oligarquía, the winners of the Invasion.

That night there was a lecture, with three speakers, at the Marriott Caesar Park Hotel, the biggest, gaudiest, most expensive hotel in Panama. It was an oligarchy event. The audience sat in a grandiose salon and listened with rapt attention to two lectures, read by important Panamanians. The subject was: ‘Democracy, Sovereignty and Invasion’. The audience, perhaps a hundred people, was mostly men, mostly overweight, wearing good dark suits. Noriega, like Torrijos before him, never touched their money or their lifestyle. But for twenty-one years, they were shelved: they had no active role in government. And they were shamed; it was shaming to be citizens of a state ruled by a squalid crook from the gutter. Upper-class Panamanians were the dissidents here. Overnight, literally, Operation Just Cause solved their problems.

The tone of the lectures was creamy satisfaction. To stay awake, I made notes among which I find the well-turned phrase ‘pseudo-intellectual bullshit’. Neither speaker mentioned the dead, the homeless, the bankrupted small businesses. I wondered if any of them had looked at the wasteland of Chorrillo. The general sense was clear enough: the Endara government was just fine; the United States was just fine; all was again right with their world.

After two long lectures, the audience needed a rest. They moved to the hall and the meeting became a cocktail party, with drinks from a bar set up for the occasion. The women, now on view, were very chic, in traditional smart little black dresses and appropriate jewellery. Everyone knew everyone else and everyone was white, the flower of Panamanian society.

After the intermission the last speaker was introduced, to applause, as ‘the next President of Cuba’. He told his reverent audience that democracy was fragile; Noriegismo was not dead; they must be vigilant to protect their regained freedom. Then he said that Latin America would not have objected to the Invasion if it hadn’t been done by the United States. Very odd. Who else would have done it? He ended with an impassioned plea for the liberty of Cuba. Was he urging a US Invasion there? A bloodbath for his countrymen? They gave the next President of Cuba a standing ovation. Some of those here tonight had been in exile in the United States for eight months, from last May – when Noriega violently broke up the election that was going against him – until the December Invasion. But this Cuban had lived in exile in Spain for thirty years; he was their hero.

The University of Panama made a pleasing contrast to the Marriott Park Caesar. It is a sprawl of grimily white cement buildings, inside and out a basic factory for learning. But the buildings, planted in a lovely jungle of trees and flowering shrubs, are linked by colonnaded shady walkways and the kids look bright and shabby and it is a good place. Ten thousand young men and women study here in three daily shifts which start at 7 a.m. and end at midnight. Tuition ranges from thirty to forty-five dollars a semester; law and medicine cost the most.

Each faculty has a students’ association, with elected officers. I was looking for Literature and found Psychology. The three officers of their students’ association sat with me in an enlarged cubbyhole off the small study room; they closed the door. They took turns talking, in low voices as if we were conspirators.

The tall, pale blond said, ‘We can say things here we would not say in public. People are afraid to talk. Some professors are in favour of this government. It is bourgeois; all of them born rich; there is no new young blood. When the United States hit us with the embargo we managed anyway; it didn’t crush us. The idea of needing identity papers signed by a norteamericano general is repugnant.’

The small plump dark one said, ‘We are all anti-Noriega but Noriega brought up working-class men and gave them positions of power. That was good. This government will keep its own class in the top jobs. We don’t think this is democracy. We are nationalists, we want to govern our country in our own way.’

The other dark boy said, ‘In this university it doesn’t matter if you are the son of a taxi driver or a cabinet minister’s son. I think the Invasion was wrong and we ought to have a free election, not this government. The curfew is spoiling our lives. We always went to each other’s houses and listened to music and talked or we went to cafés or danced. Now we can’t be out after nine o’clock for fear of running into anti-socials or gringo military patrols.’

I asked about drugs; after all, the Invasion was supposed to be about drugs. According to President Bush, drugs are America’s number one enemy, threatening its youth, its future, and drugs are not unknown in American universities. They agreed that there were no drugs on the campus and never had been. ‘People are motivated to study,’ the blond said, ‘or they wouldn’t be here.’

I went to the Law faculty next day, thinking that these future lawyers were most apt to be future politicians. A small, thin young man, elected representative of the law students’ association, spoke in a guarded voice. Strangely cautious, like the psychology students, ‘All of us here are against the Invasion. The vote last May was against Noriega but not for Endara. We should have had an election now; this is not a legal government. We are not hopeful of the future. We do not think the law will be independent and honest with this government. Already they are appointing judges, magistrates, in the same manner as Noriega, their friends, their relatives. Not on merit. I doubt if there will be an honourable system of justice in Panama for a long time.’

Pedro was the most interesting of the many interesting taxi drivers. I always sat in front, for leg room and conversation. On my last day in Panama, Pedro agreed to drive me around Chorrillo for an hour; many would not, due to the robbery syndrome. Pedro was a little, undernourished, monkeyish mulatto aged twenty-five or thirty-five. He wore a fixed dazzling smile, as if his face had frozen into this hilarity. Driving down Via España, he said, ‘At ten thirty that night I was stopped by soldiers back there.’

‘What soldiers?’ The Invasion started after midnight.

‘Panamanians. They were stopping cars to carry munitions from their Cuartel to the Cuartel in Chorrillo. but my taxi was too small. One of them fired a shot in the air and said, “Get out!” I tell you the truth, my heart was in my hands! I drove home as fast as possible. I was so full of fear that I stayed there for three days.’

‘They knew about the Invasion then?’

‘Clearly. But the people did not believe it until they heard the bombs.’ We were now in the area of devastation. ‘That was the gymnasium for Noriega’s officers.’ A big building, parts of the walls still standing; inside you could see what had been a basketball court. An old woman sat in the doorway. We drove slowly through the grey wasteland. It had been possible to raze only the stumps of the wood tenements. They must have dynamited the remains of Noriega’s Cuartel headquarters.

Pedro stopped before another large building. ‘It was three storeys high.’

From what I have seen in war, this building took a direct heavy bomb hit. Nothing else would scoop it out, leaving only jagged sections of wall. Army, which gives the most detailed record of Operation Just Cause, states that Stealth fighter planes, used here for the first time, dropped ‘concussion bombs’. So we know that planes were in action, and ‘concussion bombs’ sounds like a cover-up.

‘It was a reform school,’ Pedro said. ‘Boys and girls from five to seventeen. The Cuartel was over there, behind it.’

‘They were sleeping here?’

‘They were sleeping here.’

I do not see how any of the children could have survived.

‘Sad,’ Pedro said, his smile brilliant, his voice grieving.

‘Let’s go,’ I said. ‘It makes me sick.’

We passed empty yellow tower blocks, like Juan’s, and studied a huge hole near ground-level in a blank side of one building. The burn marks on upper floors were understandable: rockets. I could not guess the purpose of the hole, about five feet in diameter, nor what made it; perhaps some new super-bazooka. ‘This is the Model Prison,’ Pedro said. ‘Look at the wall.’ A high solid steel wall surrounds the prison; it too was pierced by a huge hole. ‘All the prisoners escaped,’ Pedro said, ‘now there are other prisoners.’

On a street below the prison, Pedro said, ‘This is the School of the Saviour. More than 300 people who lost their homes in Chorrillo live here.’ The school had been painted dark red with yellow trim long ago. On the cement front yard, half-naked unwashed kids played and shrieked. Women leaned from the windows shouting at their children and each other. It was very hot. Pedro wiped his face again with a wet grey rag. You could imagine the smell of the place. Being an old slum school, it would have a few old toilets and washbasins. Across the street the little looted shops were boarded up, except for a reopened corner grocery store.

‘Sad, sad,’ Pedro said.

‘Yes, but at least they aren’t guarded by American soldiers. They can make all the noise they want,’ for suddenly I remembered the unnatural stillness in the hangar. ‘They can walk to the centre of town; they’re in their own neighbourhood.’

‘It takes much time for poor people to gain possessions. Then everything they possessed is gone, like that, in a minute. And, who knows, relatives too. Where their houses were they see there is nothing.’ He turned his frantic smile and his sorrowful eyes to me, making sure I understood. ‘Nothing like this ever happened in Panama. Never.’

Photographs © James Nachtwey