The Hand’s Breadth Murders

Adam Nicolson & Gus Palmer

In the poor and remote province of Maramureş in the northern Carpathians, cut off by bad mountain roads from the rest of Romania to the south, the ancient body measures persist. Anything approaching six feet long – a plank of wood or a table – is a râf, the span of a man’s arms; a cot is a cubit, from elbow to fingertip; a țol – about an inch – is the length of the last joint of the thumb; and a palmă is a hand’s breadth, the distance between the outstretched tips of the thumb and fingers of one hand.

Sitting in a cafe or in people’s kitchens over a cup of coffee or a glass of palincă, the same palmă gesture recurs: the fingers held out over the table, tensed, overstretched, the most that a hand can cover. The palmă isn’t much, but it isn’t nothing, something you can imagine mattering more in a moment of passion or fear than it would before or after.

The word can turn metaphorical, so that a palmă de pământ, a hand’s breadth of land, can stand for those little patches, the slim border zones between holdings, pieces of land whose ownership is uncertain, which are also sometimes called ‘battlegrounds’, luptă terenuri, literally ‘fighting lands’. Every year in Maramureş neighbours kill each other for these contested slips of territory. At times in this mountain province there have been forty such violent attacks in twelve months, and week after week, much as road accidents are described in other parts of the world, the local press reports another man – always a man – ucis pentru o palmă de pământ: killed for a hand’s breadth of land.

After the act, the murderers usually give themselves up, shocked at what they have done, going back into their kitchens to wait for the police to arrive and, when the case comes to trial, pleading guilty, as if something had burst up within them for which they were not responsible.

I have wondered if this is a glimpse into antiquity, beyond the agreements of modernity; an archetype of the failure of human relations, or at least an eruption of the underlying facts of rivalry, loathing, violence and hatred? It is certainly behaviour as old as any record of human life. In the Iliad, Homer compared the Greeks and Trojans fighting across a blood-spattered wall to ‘two men, with measuring-rods in hand, tussling over the landmark stones in a common field’, and Patrick Kavanagh, remembering an incident at home in Ireland in 1938, when the neighbours were suddenly at war over ‘half a rood of rock, a no-man’s land’:

heard the Duffeys shouting ‘Damn your soul’

And old McCabe stripped to the waist, seen

Step the plot defying blue cast-steel –

‘Here is the march along these iron stones.’

Kavanagh called his little fourteen-line poem, in which the rhymes never quite rhyme, ‘Epic’ because:

Homer’s ghost came whispering to my mind.

He said: I made the Iliad from such

A local row.

We – I – now live almost entirely insulated from these competitive realities. Our rivalries are expressed in remarks at home, after a party when the guests have gone, or in non-replies to emails or phone messages. In that way our relationships are made and unmade almost at will. Physical neighbourhood – the ever-present neighbour-touch of poor farming life – is not like that, and seems older and more elemental. In Maramureş it is, for example, the practice to bury large stones along your boundary, only parts of which appear at the surface. They are difficult to move and it would be even more difficult to conceal the marks of their having been moved, but they also work as a kind of psychic fact. Their dark and buried bulk, powerfully present in their hiddenness, known but unseen, have threat crouched within them, the silent but implicitly violent distinction between what is yours and what is mine.

This is an old practice but there is something slightly more complicated in play than the survival of ancient behaviour into modern life. The hand’s breadth murders in modern Maramureş are something more disturbing than that, signs of modern dysfunction and dispossession, of traditional systems failing, of the modern substitutes proving inadequate, of naked, unregulated behaviour leaving in its wake decades of pain and grief, widowed women and orphaned children.

I was in Maramureş with the photographer Gus Palmer and Romanian journalist Teofil (or ‘Teo’) Ivanciuc.We went looking together for the stories behind these murders. The first piece of land we found for which a man had died was a palmă of 1,800 square metres, or 0.44 acres.

It is about fifteen yards wide and about one hundred yards deep, next to the long fast road that runs through the village of Săcălăşeni in north-western Maramureş. The village is now a dormitory suburb for the provincial capital Baia Mare just to the north, with fewer than thirty cows where even ten years ago there used to be seven hundred. An air of lifelessness hangs over it, with no one about in the daytime. On the patch of murder-land, which has been uncared for since the killing, you have to push through a thick pelt of buttercups and foxtail grasses to reach the willows that are now springing up along the boundary fences.

Just along the road, the dead man’s brother, Ciprian Radu, is living in a small house at the side of an unused yard – no animals, no muck. This is the house where his brother was killed three years ago. It is a weekday mid-morning. Ciprian is welcoming but he has been drinking and his handsome, high-cheekboned face is flushed and puffy. There is a smell of drink in the air and both maleness and poverty seep from the walls. A soft-porn calendar hangs in one corner of the living room, a tapestry of da Vinci’s The Last Supper is up behind the sofa, there is a crumpled paper icon of Christ pinned by the door and, on the television, people in traditional Maramureş costumes perform songs for a bare-shouldered hostess while colours flicker on the set.

In April 2012 the three Radus – Ciprian, his elder brother Calin, a big man aged thirty-five, and their younger brother Petru, twenty-eight, anxious and flighty – were here in their grandmother’s house. It was a holiday, one week after Easter, in the middle of the day and they were drinking: palincă, the plum brandy which features in most of these stories. Calin, over eighteen stone, had just been left by his wife. He was unhappy as she had kept the children. Petru was getting overwrought. ‘He had a nervous disease,’ Ciprian says. And so Calin rang for an ambulance to take him to hospital. ‘But Petru could be aggressive when he was drunk.’

An argument started about the land. Calin had been working for many years in England, as a builder and in a car park. He had also had some money from their mother. Petru suggested they sell the land down the road – it had belonged to their father – but insisted that the proceeds should be shared only between him and Ciprian. Calin surely had enough money already. ‘I was trying to separate them,’ Ciprian says, ‘but I couldn’t stop them arguing so I left.’ It was a familiar situation: they had been arguing for years and Ciprian was away from the house for about forty minutes, to visit his aunt, but more than anything to escape a scene he hated.

When he was away, Petru, who was only eight or nine stone, took a knife that happened to be lying on the table, simply to threaten and scare Calin. ‘He just touched him with the knife on the right shoulder, not a deep one. He had no plan to kill him but he just touched the artery and the blood started to flow. Just there.’ Ciprian pointed to the corner by the door, the brown carpet below the paper Christ.

Ciprian is anxious with the memory. ‘When I came back, the knife was outside, covered in blood. Calin was lying down here on the bench still alive. The room was bloody and he was pale and bloody. Petru was lying on the other bed here.’

By the time the police and ambulance arrived Calin was dead. ‘I thought when I went away the fight was just with fists, but when I came back I saw the knife and I understood what had happened. How easy it is for someone to die. It was almost an accident. How easily someone can die. A little stab and someone dies. It was that, a little stab.’

Ciprian seemed still to be suffering a form of shock. Something was inexplicably missing, the dead brother removed from life as if by a force that had arrived momentarily in this house, leaving him pale and gasping on the bench, and then killing him.

Petru tried to plead in court that he had acted in self-defence, that Calin had come for him, but there were no witnesses and the magistrate did not accept the plea. The crime was thought particularly severe because it was brother murdering brother, a breaking of bonds within the family. Petru was sentenced to pay one hundred euros a month (about a quarter of an average monthly wage) to the dead man’s little daughters, and the judge recommended that Calin’s widow should have the equivalent of €20,000 from the murderer. She refused to ask for it ‘because she understood it was an accident. And knew that Petru did not have this money.’ Or so Ciprian says. Petru is in Gherla Prison now, a place for serious criminals, sentenced to ten years, as severe as any hand’s breadth murder sentence because, as Ciprian says, ‘They were brothers. The accidental nature of the crime was not taken into account.’ He will probably be out in five years. Calin’s widow now lives in England. And the family goes on as if catastrophe were part of the weave of life.

Every piece of land is important here. People in Maramureş, with an inheritance of poverty and crowdedness, are what they are because of the land they have. Land is a constituent of the person. To enter another man’s land, particularly the yard around his house, is as intimate a penetration as putting your fingers in his mouth. A sophisticated, multilingual journalist in Baia Mare, who did not want to be named, told me that if someone came ‘into his land’ – that was his expression, as if the land were an entirely enclosed space – he would kill him. ‘It is a border he has crossed. And when he sees my eyes he would understand. It has happened to me, men coming onto the land with guns. I told them they had to leave within ten seconds. “If you enter again, I don’t give you the chance.” ’

One evening in the main street of Săliștea de Sus, a big raw-boned village in the valley of the River Iza, we talked to an old lady called Ileana Vlad. She was sitting and knitting on one of the ‘gossip benches’ that line the street outside every farm gate. Things were not going well, she said quietly.

‘My husband died on the fifteenth of December. Now I cannot find a little pig in the market. And you can’t live without a pig and some chickens. It’s only women left now. All the men are in the cemetery. A life without a man is not worth living. Why not? Because there is no one left to do the repairs! What can we do?’

She was knitting a black winter waistcoat with sparkly red and green threads in the wool. I asked her about land murders in the village. Not pausing from her needles, she said, ‘Oh yes, a man killed a shepherd two years ago up there’ – she pointed to the meadows on the valley side high above us, below the forest edge, where the cherries were in blossom and the beech trees were coming into new leaf. ‘He killed him with a fence post; he shoved it into his mouth’ – she gesticulated – ‘because the shepherd walked over his land with his sheep. One eye of the shepherd jumped out onto the ground when the stick went in. He was from Moldavia.’ This unlikely phenomenon appears in the Iliad too, when Patroclus smashes a stone into the forehead of a Trojan prince Cebriones ‘and both his eyes jumped out into the dust at his feet’.

Ileana’s lack of surprise, the click of her needles, her acceptance of extreme violence as part of how things are, the making of the winter waistcoat in the warmth of the spring sunshine, the need for a pig – all of it is part of a phlegmatic attitude to life, a lack of fuss at how difficult existence can be.

In the outdoor ethnographic museum in Sighetu Marmaţiei – a project of the passionately nationalistic Ceaușescu years – where the most beautiful examples of Maramureş wooden architecture were gathered before they disappeared from the villages, there is one house from Vadu Izei, a few miles up the road from Săliștea de Sus. It had belonged in the late nineteenth century to the two Arba brothers. When their parents died, they could not agree on how to divide their inheritance. Rather than kill each other, they decided, in effect, to kill the house and together sawed it in half. One half remained in the old farmyard with one brother while the other took his timbers and rebuilt his half in another part of the village. Only in 1970 did the museum in Sighetu buy both halves where they are now reconnected as a single house.

Walk through any of these valleys in the springtime and nothing is more impressive than this all-embracing physicality – the intimate connection of body with place and mind, the ways in which the physical elements of existence are dense with social and emotional meaning. One morning early last May, Gus, Teo and I were walking along the lanes of a little side valley above the River Iza, near the big village of Ieud. It was the moment at the end of winter when the land has to be ‘arranged’, as they say; cleaned and cleared for the growing year. People – mostly the old; not the young men and women away earning euros – were out on the roads. Farms are tiny – half of all the nine million farms in the EU are in Romania – and made up of even tinier strips scattered across the parishes. Almost no one has a car and so this is a walking world. No motor noise, no jet sound. Cuckoos and woodpeckers in the woods, skylarks above us, cocks crowing in the farmyards. The whole valley was filled with people ploughing, hoeing, axing out the dead wood, levelling molehills, cutting bean sticks, planting potatoes, raking old leaves, putting out dung. Women walked at the heads of the horses, the men behind at the wooden ploughs. Pastures were being scoured with ox-drawn dredges, ploughlands broken up with horse-drawn harrows. The last cartloads of hay were being taken back to the winter barns before the cattle were let out onto the spring grazing. The only sound on the road was the oiled creak of the cart axles as they passed.

It is easy enough to feel bewitched by the charm of this landscape, of people living in an animated, Bruegelian, pre-mechanised world, as if the experiences of Coleridge in Germany in 1799 or of Goethe in the Roman Campagna were still available to us now. The whole of Maramureş is like the Arba house in the Sighetu Museum: if you didn’t know better, you might think it perfect – that no damage had ever been done. But then, in another light, you see the tools of violence being carried into the fields: the steel crowbar, the ranga, for making holes in the earth, the axe with its bright and burnished edge, the cleft oak posts, the hoes, the hedge slashers – all the instruments with which control and management can be imposed. Cutting, controlling, slicing, hacking, killing: these are aspects of everyday existence.

Vasile and Ioana Sas were walking along the road, an axe and hazel-handled rake in his hand, a checked work bag and hoe in hers. They were off to arrange some of their land. She walked on but Vasile stayed to talk.

He has twenty pieces of land and walks to all of them ‘because I like walking!’ He grows potatoes and beans and hay for his two cows. As we talked you could hear people having conversations half a mile away on the far side of the valley and the crackle of their fires as they burned the dead branches that the winter snows had brought down. Some of Vasile’s pieces of land are miles away. How far? I asked. ‘Oh, over there.’ He pointed to a horizon where the snow was still lying in the forest. ‘The other side of that, twelve miles from the village, each way.’

Land matters in Maramureş and ownership is a form of emotion here. A cluster of Romanian terms, all with the root mos, emerge in words meaning ‘giving birth’, ‘inheritance’ and ‘land’. Land is memory and family, a form of manhood and womanhood, a way of being in the world, a mooring and fixity, a tangible identity beyond the fluidities and threats of life. ‘Without land I always felt anxious,’ one Transylvanian farmer told the anthropologist Katherine Verdery. Earth is flesh here.

Both geography and climate reinforce the idea of defensiveness as the core relationship to land. Maramureş is almost entirely mountain, high, hard and forested. Wolves and bears still live here. The only valuable land, from which bread can actually be derived, is down in the narrow valleys, where people cluster, where villages are almost continuous ribbons of buildings along the valley roads, and the strips of land are as treasured as any family heirloom. ‘We are Maramureş,’ Teo said only half ironically. ‘We are very aggressive, very nervous. Everyone here will always reach for the knife in his pocket.’

The ethnic mix of the country also plays its part. A large majority is Romanian but scattered in among them are villages of Hungarians, Germans, Ukrainians, Gypsies and even Armenians. Your own land has its boundaries, but your language community is limited too. Even within the Romanian valleys, every village tells contemptuous stories of every other: the people of Bogdan Vodă have no forest left because they burned all their wood in the distant past, trying to boil a boulder which they thought was the egg of a dinosaur; the inhabitants of Săliștea de Sus are ‘bumblebees’ because a half-deaf old lady once heard the noise of a bee trying to get out of a window, thought the Tatars were coming to kill and rape them all, rushed to ring the bells of the church and the whole village ran away into the mountains and the woods; those in the very poor village of Strâmtura are called ‘the ones who put the bull on the church roof’ because in a drought they ran out of grass but decided they had to save the village bull. The men of the village hauled the bull up on the roof of the church, but by the time they got it up there it had died from the strain.

This is high and late country. The growing season was always thought to be one hundred days at best (that has lengthened with global warming), limited by frosts in May at one end and heavy rains in September at the other. Life had to be squeezed out of that growing year and most families were unable to survive without the wages earned by men labouring elsewhere in Romania and Austro-Hungary. ‘People here have always been fighting for their life,’ Dr József Béres of the Sighetu Museum says. ‘The land is mine, it is my family’s, it came from the past. The word peasant might mean “a man in love with the land”, but there is not enough land. Big land was always occupied by the nobility and so the peasants were always short of it. It is a form of devotion but also of unending anxiety and desperation, a predicament shared with every neighbour you have.’

In 1848, the Transylvanian serfs were liberated and a large land-owning peasantry developed. From the 1860s onwards, each fragmented, multi-strip holding was carefully mapped and described in a meticulous Austro-Hungarian cadastral system. There were many local ways of policing this complex pattern of land ownership. Villages employed field wardens, gornici, to mediate in arguments between neighbours: where the boundaries lay, where cattle could or could not graze, whose hay grew in which meadow. The gornici were organised by a birau, a ‘mayor of the fields’, paid by the village, either through a local tax or by receiving the fines raised from malefactors.

But little was stable here. After the defeat of Austro-Hungary in the First World War, 3.9 million hectares were distributed to Romanian peasants; in 1945 a further 1.4 million hectares were expropriated from the German peasants and one million hectares redistributed. Communism and the collectivisation of most farmland in the decade after 1949 was only the most radical link in this necklace of disruptions. Along with the local authority of the priest, the council of elders in each village was done away with. Most land and all tools were gathered up, even the yokes of the cows, the ploughs, the wheelbarrows. The agents of the party, the New Men, usually the landless, the poorest in the village, became the agents of confiscation. People talking of that time can become speechless with the pain of it. The richest and most influential villagers, who employed others or had wide networks of cousins and supporters, were given impossible quotas or tasks – to plough, for example, their entire ten-hectare holding in one day – and could be imprisoned if they failed.

The New Men began to impose collective solutions and in the 1950s violent neighbour-hatred ballooned. Administrative change can scarcely address the loyalties of the heart and, needless to say, ancient memories of possession and belonging persisted under the new collectivised regimes. Those ghost memories of ownership – with the pain of dispossession rising up into the surface of everyday life – lie behind the murder of a farmer called Todor Lumei in the autumn of 1972.

His daughter Viorica, now fifty-seven, lives next door to her sister Maria, five years younger, in the house they were both born in. It is on the western edge of Sighetu Marmației, tucked up in a little valley, the whole of which once belonged to their family, above the River Tisza. From their land they can look out over the gantries and towers of the salt mine at Solotvyno across the border in Ukraine and to the dark, cloudy forests beyond it. The sisters have divided the small wooden house in two and each has raised a family in their own inherited half. Cherry and apple trees blossom around their yards and gardens where the onions are already set. Dogs are kept in wooden runs, swallows sit on the telephone wires and chickens peck among the fallen blossom petals on the grass.

The worn air of loss fills Viorica’s hot yellow kitchen. She tells the story, twisting her hands, folding and unfolding her fingers, while Maria listens, playing with the buttons on her phone.

‘We were poor because our father died very early,’ Viorica says. ‘The whole hill here was once owned by our grandfather. But during Communism many others were settled here. The road is still our property but . . .’ A shrug and half a smile.

‘I was fifteen in 1972. It was in the autumn. And I was grazing the sheep with my younger brother. He was fourteen. We were looking after the lambs in the field up here’ – she points to the hill behind the house – ‘and the lambs went off into another piece of land, part of the collective farm then, and they ate some hay from the collective farm haystack.’

Next to that haystack was the little wooden house and yard of the man who had made the hay for the collective. It was not his hay, but he had done the work and built the stack. ‘His wife started to shout and scream at us from her yard. “What are you doing? Your lambs are eating our hay!” ’

Just then, by chance, her father came up the hill. He heard the woman shouting at his children. ‘So he said to her, “Why are you making that noise? Why are you arguing with the children? If you have something to say, say it to me. I am here.” He went into their farmyard to deal with it. “If I did something against you, just tell me, we can sort it out.” ’

Then the neighbour’s small dog tried to bite Viorica’s father. All his attention was given to keeping it away. And while he was concentrating on the little dog, the woman came up behind him and stabbed him with a little knife in the back. ‘He was not deadly wounded,’ Viorica says. ‘It was just a small wound. He didn’t pay attention to it, because he was still fighting the dog. Then the woman shouted, “Come and kill him! If you don’t come and kill him, I will kill you!” Her husband came out of the house with an enormous knife and stabbed my father with it in the back and he fell down dead in one second.’ With her hands she measures out the length of the blade on the plastic of the tablecloth, about two feet apart, each hand slightly cupped.

Viorica shouted for her brother and when he got to her and saw what had happened, they both started to scream so loudly that they could be heard in the town of Sighetu. Her brother ran down the hill to call for help. The murderer ran down after him, trying to stab him too, but he escaped. Then, quite suddenly, the murderer came to his senses and went into his house, with his wife, to wait for the police. Viorica stayed in the farmyard by the body of her father on the stones and the muck from the animals.

The neighbour was arrested. At court his family arranged things so that the wife was not accused and the murderer was sentenced to eight years, so little because he was already sixty-eight. During Communism, many general amnesties were issued and after one year and two months he was released. ‘For such a murder,’ Viorica says, half under her breath.

Compensation was set by the court. The neighbour was employed by the collective farm and sold his animals to pay the lawyers, so there was nothing left to give the children in compensation for their father’s life. The murderer had no goods, so they received only his small wooden house: ‘Seven by four metres, a room and a porch.’ It was valued at 17,000 lei, fifteen monthly wages at that time, but that figure draws sceptical laughs from the women. ‘It was worth much less but we took it,’ Maria says. ‘It was rotten, very rotten and so we didn’t have much timber from it. We built a barn with it.’ The man’s wife died when he was in prison and afterwards he moved away. ‘And can you believe,’ Viorica asks, ‘he lived until he was over ninety?’

What explains this? Why the rage of the murderer’s wife? There had been no trouble before. But the ghosts of history were in play. The murder site had never been part of Maria and Viorica’s grandfather’s property, but memories of class distinctions hung on. They had been rich peasants; the murderer was the poorest of the poor. The land on which the haystack stood and on which he had made the hay had been his before collectivisation. And so rage and resentment and the grief of loss found its outlet in this. Had their father somehow, even inadvertently, been acting the richer peasant? Had the murderer’s wife thought he was coming for a fight, and so attacked him first?

These questions drift around the kitchen, as they have these last forty years. After the murder Viorica went to work in a restaurant and then a hospital to help her family. She has been sick ever since. ‘I was so deeply affected that I have had several strokes. Of course you can never get away from it. It is always in your mind. It is always in my memory.’ Their mother fell sick. The family borrowed money from relations for the funeral and to cover the fees of the priests, working for years to pay them off. Grief took up residence beside them.

We went up the hill to see where the killing had happened. The meadow has been planted since then with a new plum orchard, the trunks painted white, the trees coming into leaf, the blossom already falling like spring snow onto the grass. A neighbour saw us walking up there. ‘Look,’ Viorica shouted. ‘We have found some boyfriends so we are going out into the woods!’ But it was no weather for picnics.

The revolution of 1989 released a surging demand for restitution of the lands that had been collectivised during the years of Communism. Over 1.5 million Romanian farmers started court cases against their neighbours for land claims in the 1990s. Those who had been using the land during Communism thought they had as good a claim to it as the descendants of those who had owned it before. Many of the descendants had moved away and were now in the cities. How did they have more of a right to land than those who had been working it for decades? Corruption and complexity swamped the process. Village land commissions, run by the mayors and deputy mayors, became the means of rewarding friends and punishing rivals. Land which had been built on entered an ambivalent state: who did it belong to, the original owners or the owners of the houses? It was decided in the 1991 legislation that those who once owned the land on which others had built now lost the right to one thousand square metres of it – the area occupied by a house and a small garden – but could claim the rest of it, plus an equivalent of the one thousand square metres in another part of the village. But this meant that land had to be invented.

People had forgotten where their land was meant to be. The cadastral maps, which were ignored by the Communists and recorded nothing that had happened since 1948, were rejected in favour of hazy witness statements. As Verdery has described:

Fields have drifted from their original moorings in space. Even reference to the roads or ditches was not certain, for these too had changed in the meantime.

Earlier she had written:

Whole fields seemed to stretch and shrink; a rigid surface was becoming pliable, more like a canvas. It was as if the earth heaved and sank, expanding and diminishing . . . How can bits of the earth’s surface migrate, expand, disappear, shrink and otherwise behave as anything but firmly fixed in place?

Verdery has said that decollectivisation ‘became a war between competing social memories’ – between those who thought a pre-Communist system was restorable and those who treasured their own immediate pasts in places they had come to think of as home. It was a war fought, she says, ‘on shifting sands, for the surface was now wholly relativised.’

By mid-1994, 6,236,507 claims had been filed for the return of land. 4,897,573 were accepted, for a total of 9.2 million hectares, two thirds of Romania’s farmland. Just less than half of all holdings were under one hectare, 82 per cent under five hectares. But fog still hangs over the whole process. It remains unclear whether there are twenty-three million or forty-five million separately owned parcels of land in Romania. Poverty governed the territory; the price and number of horses both rose in 1990s Romania as few could afford any other form of farm equipment. What now looks like traditional peasant agriculture is in many cases not the persistence of ancient patterns but a symptom of the collapse of what had been a relatively advanced form of collective agriculture. In some ways, Romanian farmers were demodernised in the 1990s.

In this last great twentieth-century dissolution of the known order, hand’s breadth murders peaked again and on into the new century, just as they had in the 1950s.

It is Saturday and Marisca Orha, the seventy-five-year-old widow of Ioan Orha, is in the kitchen of her house in Tămăşeşti, a village out in the rich, open country in the west of Maramureş. Her daughter Rodica, who lives in Baia Mare where she runs a tyre business with her husband, is visiting her mother as she usually does at weekends. Together they are brushing up the feathers on the earth floor from the chicken they have just plucked. Its naked body is lying on the table, with a stump where the head once was. A pot of something is stewing on the stove.

‘He wasn’t guilty,’ Marisca says when we ask about her husband. There is another hen and thirteen little chicks in a small enclosure by the stove, and while Marisca talks, the hen clucks quietly over them and they cheep in reply. ‘He died for nothing. The piece of land, it is just along there. You can go and look at it if you like. Go later. Have some wine. Nobody enters my house without receiving something.’ She brings a plastic bottle of her delicious fruity wine, the smell of grapes still in it, and Rodica fetches a big hank of paprika-stained lard which we eat in little rectangles with bread and peppers. Her kitchen is filled with an enveloping warmth.

Her husband’s great-grandfather had taken care of the land during the war. Originally it was 1.5 hectares, although now it is only a third of that, 4,600 square metres, just over an acre. At the time, under the fascist Hungarian regime then governing Transylvania, he had also taken care of the Jews who owned it. Until May 1944, there were about 40,000 Jews in Maramureş working in the villages as farmers, shepherds and foresters. Some five thousand of them survived Auschwitz, and after the war the Jewish family that owned the land gave it to Orha to thank him for the trouble he had taken over them. ‘All officially done,’ Marisca says, with a rising urgency in her voice. ‘All with papers.’

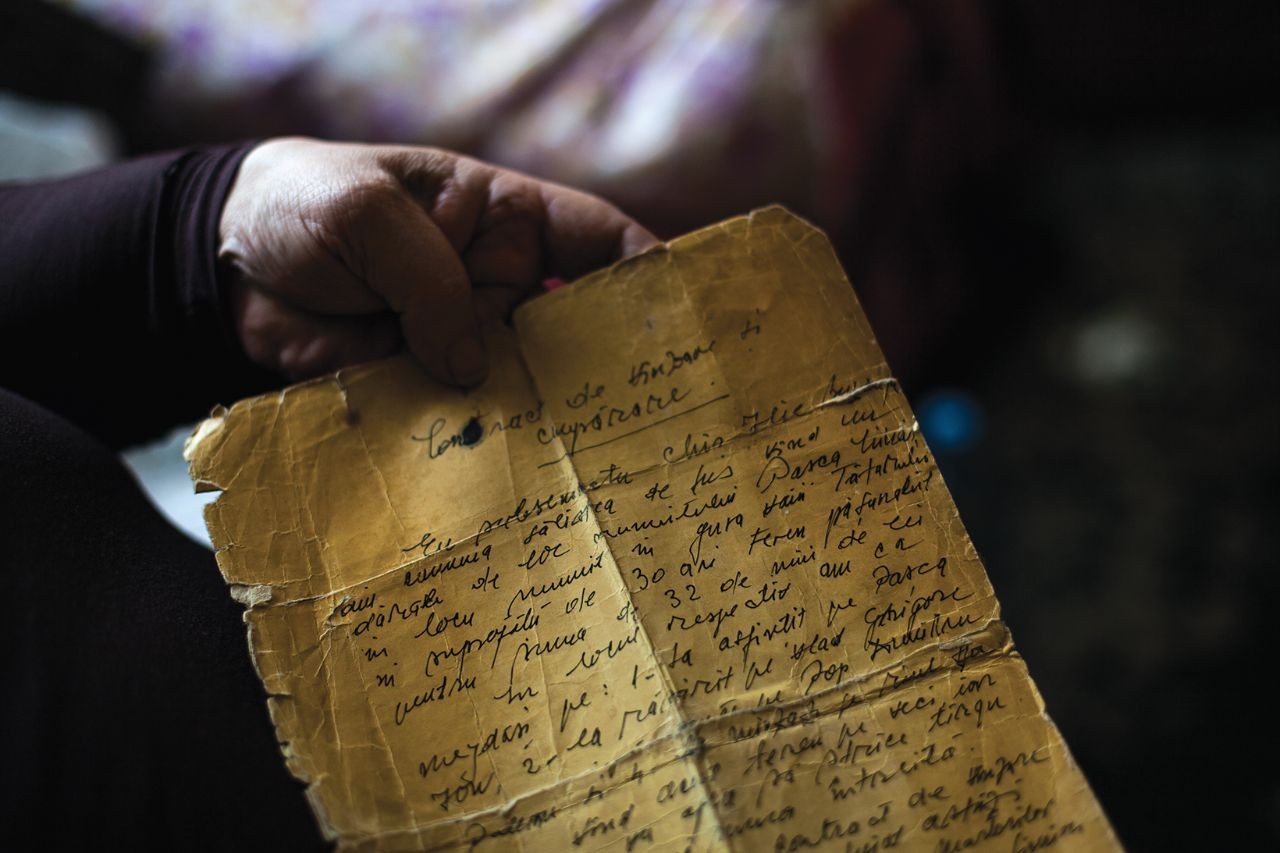

During collectivisation the Communists took the land and made parcels of it, distributing it to different families to use. ‘And after the revolution each farmer moved back to his old field that was previously his own. But with this piece of land – it is called Ograda Jiga from the Jews who had it before – one family said that it was theirs. They had been working it for as long as anyone could remember. Even though Ioan had all the papers proving his right of ownership.’

The other family was called Sabou, and in 1997 the case went to trial in Baia Mare. ‘Father was very busy with his work here,’ Rodica says, ‘and so he did not go to the trial.’

‘We had no money to pay a lawyer,’ Marisca says. ‘We thought if we had the papers it was enough and we didn’t need a lawyer.’

‘But he lost because he was not there. We made an appeal but we lost that too and so we abandoned the field.’

Nobody used it for fifteen years. The land lay neglected, a weed-filled strip, ‘unarranged’, between pieces of land that the Orhas farmed carefully, planting them with maize. In March 2012 a young man from Baia Mare called Marinel Daniel Sabou, the thirty-year-old nephew of the Sabou who had won the case, needed it to graze some sheep he had just bought. ‘Sabou came here to see the boundary with his friend Petru Pocol. They came into the courtyard to ask Ioan to show him exactly where the field boundaries were, just to check they weren’t trespassing on another man’s field. So he went with them.

‘When he arrived back he was bleeding. He said,“I am dying.” He said that here at this door. “I was heavily beaten by them.” ’

Why?

‘Because when they arrived at the land, they said, “Let’s measure it with our feet.” “No,” he said, “bring a tape. Doing it with your feet is not good enough. You can get it wrong so easily with your feet.” ’

Now, with the memory, Marisca begins to shout in her kitchen. ‘They were so angry. They kicked him here’ – she put her hands to her ribs and stomach – ‘until they broke his organs inside. He came back in such a bad state, so we called the ambulance and police.’

Why did they do it?

‘They were just angry and they turned to violence.’

‘It was a Saturday,’ Rodica said, ‘and the police told my mother: “We don’t come out for such a small case.” ’

‘He was lying there on the bed then,’ Marisca went on. ‘They said: “You, Marisca, you must come to the police station on Monday to report it.” ’

An hour later the ambulance came but while she was waiting Marisca took a hay fork and went herself to the field and found the two men there.

‘Your husband was lucky,’ they said to her. ‘He was not young enough. If he had been young enough to fight we were going to kill him, but we decided not, so we just left him lying there because he was so old.’

She pushed the hay fork at them. ‘ “You bitch,” they said to me. “You thief.” ’

His spleen, the doctors said, was not broken. It was ‘exploded’. He lost 2.5 litres of blood to internal bleeding. They operated on him as soon as he arrived in hospital, but they could not do much, and after five days in intensive care he died.

Two weeks after the funeral one of the Sabou cousins came up to Rodica in the street in Baia Mare and proposed to make peace. ‘It is a shame that such a young man should go to prison and your father was old and not far from dying anyway.’ She told him that she had nothing to say and justice must follow its course.

The next time the Orhas saw the young men who had killed their father and husband was at the trial. As Marisca caught sight of them she had a heart attack. Since then, she has had two strokes. ‘The worst part for me is that he died for nothing. He wasn’t guilty and for that I suffer, still today.’

The men were both given eight years in prison, of which they will probably serve four, contemptible sentences which are the surest sign that the process was corrupt. Even today the land is empty. No one goes on it. Rodica took us there in the light spring rain, smoking with the anxieties of memory. ‘They never came back to graze it. It is all for nothing. My mother is suffering a lot but she is a fighter. She never stops.’

Goldcrests chirred in the hazel clumps beside us. Did Rodica have any photographs of her father? ‘No. I have taken them all to Baia Mare. It is not good for her to see him now.’

Back in the house, Marisca looks up at me, a golden tooth in her smile, her flowery, black-and-white apron like something a girl would wear, her black scarf on her head. ‘They came in March, that heavy day, just to measure the border. “Come with us,” they said. And so he went.’

Can one see any of this from the other side? Is it really possible to regard murder, as the laughable sentences handed out to the killers imply, as a normal part of everyday life? Of how things are? Of what men do to each other – as unfortunate spontaneous eruptions of anger which do not need to disrupt the flow of life? Could I see how these land murders looked from the point of view not of the victim’s family but the killer’s?

There had been one particularly horrible murder on the edge of Săliștea de Sus, where the victim, Ianoș Pașca – a big, violent and angry ex-miner from a family of famous anti-Communist partisans – ended up lying dead in the shallows of the River Iza. The local press had been able to photograph him one long afternoon in May 2009, his shirt up over his hips and the back of his head bloody.

He had been sitting on the riverbank across from his house, just at the spot where a favourite cousin of his had been killed years before, accidentally electrocuted when illegally electrofishing in the river. Pașca had bought the land a few years previously – good valley land but only 1,800 square metres, or just less than half an acre, a palmă de pământ, something and nothing – because it was ancestral ground. His grandfather used it but his father had actually bought it and then given it as a dowry for one of Pașca’s sisters. Pașca then ‘paid good money for it’ – 30 million old lei or about €750 – to his sister. His wife, Ileana, had urged him not to buy it because, as she said to me, ‘Everyone wanted it. It was fighting land. There were many other things he could have bought but he bought that land. His mind was fixed.’

The person who wanted it more than anyone was Pașca’s cousin Mărtin Grad, a small man, known as Mărtinuc or Little Martin, who lived in the same village. His father and Pașca’s were brothers, and Mărtinuc and all the Grads thought that in some way, despite the documents to the contrary, the slip of land, just at the point where the side valley called Tătarului comes down to the Iza, should belong to them. Pașca and Mărtinuc had been at each other’s throats for years. Pașca had complained more than twenty times to the police that Mărtinuc was threatening him. And he had said to Ileana, ‘I am going to kill him.’ She had said, ‘Don’t touch him. You only have to hit him and he will die.’

The palmă de pământ is a sweet spot: the green sward in May is covered in dandelions and daisies. Pear trees run along the public road, loaded and thickened with blossom. Willows have been pollarded on the riverbank itself, and there is a woodyard to one side, tangy with newly cut oak.

On 21 May 2009, the feast day of saints Constantine and Helen, Mărtinuc had been drinking with a friend. It was a holiday and just before four o’clock in the afternoon he stood up and told his friends, ‘Now I am going to kill someone.’ Pașca was sitting on the river- bank with Mimi, his treasured three-year-old granddaughter, in his arms. Mărtinuc crept up behind him and hit him in the back of the head – it is generally thought with an axe, or perhaps with a split-oak fence post. He tried to kill Mimi too, to get rid of a witness, but he was drunk and she ran away. She remembers her bag dropping into the river.

Mărtinuc went home, said, ‘I killed him,’ and waited for the police. He was given twelve years, will serve six and is due out this year. Pașca’s widow Ileana was awarded 100 million old lei compensation for murder, about €2,300, but she has yet to receive it. Worse than that, when she came home from court and walked past the gate to the killing land, Mărtinuc’s family, quite illegally, were there with their hoes and forks. As she walked past, one of them said: ‘We will kill you just as our father killed your husband.’

Ileana Pașca lives in a state of dread. She is sixty-seven and has spoiled her eyes ‘with cheap Russian glasses’. Her face is saggy with emotion and exhaustion. Mimi, her granddaughter, spends much of her time with her, solemn and almost entirely silent, perhaps permanently traumatised by the scene she witnessed six years ago. Meanwhile, gossip ripples around the village: that Mărtinuc had been looking after the chief of police’s sheep; his children had been making the chief of police’s hay. Mărtinuc himself had been in the front row of church every week and the priest loved him. Ileana told me that the priest had even visited him in prison and urged her to forgive him. To which she shot back, ‘If your wife had been killed, would you be ready to forgive the murderer?’

I started asking in the village for Mărtinuc’s family. It wasn’t easy. Mărtinuc? Mărtin Grad? Aren’t there two people of that name? The one who killed that man by the river and walked off ? Oh no, I don’t know that one. I know the other one. Then going on their way down the village street, the relief palpable in their bodies, the cigarette in one hand, the small black hat resettled on the top of the head. Or, with people who were connected to him, that look of difficulty and defence, of thoughts in mind that are not to be expressed, an inwardness, a retraction below the surface of the face, even while stirring the coffee or working the till. No, not a nice person. It isn’t enough to go to church. He wasn’t a good Christian. Perhaps even a false Christian you could say. Not an honest man. And that result was final proof, wasn’t it? People had entertained their suspicions before.

A man drinking coffee in the Irimi cafe bar, Dan Iuga (he had lost his right index finger to an axe: ‘No problem! One less fingernail to clean!’), thought there might be a relation – Mărtinuc’s daughter’s mother-in-law – living just along the street, but it turned out she was away in hospital in Cluj. Ioana Iuga, running the bar and related both to the Grads and to the Pașcas, thought maybe Mărtinuc had some relations living up the little narrow valley called Tătarului, up in the hills, the very valley at the foot of which he had clubbed Pașca in the head.

A stony lane curls its way up the valley alongside the stream, with willows and cherries in blossom the length of it. Here and there are tiny poor farms. The wild and its threat are not far away. It is called the Tatar Valley, a name which suggests that, as an impoverished valley on the very edge of things, it was somewhere for the poor, marginalised sub-groups of the Tatars, not good enough for Romanians. Over the poultry runs, single, tattered chicken wings hang from willow sprigs to keep the hawks away.

Little strips of meadow are slipped into the foot of the valley. Most of the ground is too steep to plough or dig, so steep, one farmer told us as we passed, that the upper plough horse would always be tumbling down over the other if you tried. The forest is a solid wall above the lowest few yards of the valley, full of oaks and new beeches, their leaves alight with spring green. High cherry trees were blazing like lanterns among them. Thrushes and blackbirds sang in the shadows. Pied wagtails dipped and bobbed on the river stones. It is bear and wolf country. Three years ago, one winter night, 150 sheep and eight dogs were killed by a pack of three wolves about fifteen miles from here, outside Rona de Jos. Teo was carrying a pepper spray in his pocket, more for the dogs than anything else. ‘I have been bitten too often in places like this.’

We asked at the little houses for Mărtinuc’s family. ‘Yes, further up’ – that waving, flicking hand gesture meaning ‘not here, up there, further away’.

Finally we came to the place where they said Mărtinuc’s daughter lived. Three dogs on chains guarded it from any approach. Each dog had worn to dust the ground within the reach of its chain. A tiny cabin, scarcely a house, stood a yard or two inside the fence and gate, with a ragged broken henhouse and pig house beside it. A haystack stood in the yard and chickens picked around the straw. There was no spot of level ground. Five yards from the door of the house, the wall of the valley rose into the forest. Washing hung on a line attached to a cherry tree.

It was a beautiful corner but no one would live here unless they had to. And thinking of those lovely level square metres of land by the river, where a family could spread itself in ease, and with the knowledge that whatever they planted would grow in the alluvium on which they lived, you might well feel that envy and hatred was inseparable from being stuck up here in the beauty of this hard and impoverished place.

We stood at the gate and a middle-aged woman came out of the house, short-sleeved shirt, strong arms, an unquestionable presence about her, and we began talking. She was Ioana Grad, Mărtinuc’s daughter, married to Ioan Vlad who was away this afternoon working on the railway. Her son-in-law was on the far side of the yard, clipping the wool from an old ewe, with his wife and baby daughter beside him. He saw us, stood up and slowly walked over, the pair of long-bladed cutters in his hand, held out in front of him, the blade upright, his fist around the handle resting on his thigh, his eyes under a peaked forage cap intently fixed on us as we stood there outside the yard, talking to the woman across the gate, not crossing the all-important boundary. The last words of this family to Ileana Pașca were in my mind. There is no mistaking the big, swinging, self-establishing manner of a fighting man and we reacted as animals do in these circumstances, looking down and away, no meeting of those eyes, no encounter with the cloud of defensive, frightened aggression he was emitting, nor with the cutting blades held out in front of his thigh.

We talked about the EU, how no grants were available for farmers with less than fifty sheep, or farms as tiny as theirs; about the valley, their goats, the weather and the bears. ‘Is that why you are here?’ Ioana asked. ‘Because Ioan was bitten by the bear?’ ‘Ah yes,’ I said, ‘because of that.’ And with this talk the air of threat and distance started to shrink away. The son-in-law Stefan lowered his blade and Ioana asked us into the house. She had just baked an apple cake. Would we have coffee?

We sat beneath a small Day-Glo icon of the Holy Family at a table two feet square, covered in a plastic lace cloth. There were geraniums in pots growing in the window. They had tried to grow medicinal herbs here, but the plants had never thrived. They had made thirty carts of hay on the high meadows last summer and brought them down on sleds over the snow in the winter. They felt they had nowhere to go, nowhere to be. Unlike other, richer families from these valleys, they don’t have the resources to go west within the EU to earn the sort of wages that can buy cars, build new houses and change lives. ‘But you want to know about Ioan and the bear?’

It was 1991, the fourteenth of September, the Day of the Holy Cross. At ten in the morning, Ioan Vlad was looking after the cows only a few yards from the farm on the edge of the forest when a bear ran out between them. After Ioan hit it with a stick the bear put a thumb into Ioan’s mouth and grasped his face with his other claws. ‘With that one hand the bear broke all the bones in Ioan’s face. He did not pull his face out but he broke it all,’ his wife said.

Ioan, as they were fighting, with a presence of mind it is difficult to imagine, put two of his own fingers in the bear’s nostrils so that it couldn’t breathe. The bear dropped him and ran away. Ioan was screaming with pain and the neighbours came running from farther up and down the valley. His head was soon swollen to the size of a melon and they carried him down to the village, past the Pașcas’ house to a place beyond the river where there was a telephone and an ambulance that could take him to hospital. ‘All his body was torn because the bear had played with him. In Cluj, he had seventy-two operations on his face and still now he cannot eat easily because some of the bones in his head are still loose. And one of his eyes can no longer have any tears.’

Is that why they have so many dogs chained up around the edge of their place? ‘Well, for Gypsy thieves, for foxes, for wolves, for hawks. You never know. For bears. For strangers. For our enemies.’ Then looking out of the open door, to the lane and the stream and the steep far wall of the valley, filling the space of the doorway, no more than twenty yards away, ‘Do you know how much I like to talk like this?’

Ioan returned from work, one half of his face visibly slumped and broken. ‘Everything you see on my face was down,’ he said. ‘You could see the other side of this eye. And this is the eye from which tears will not come now.’

While Stefan and his wife Maria returned to clipping the urine-coloured wool from the old sheep, Ioan took me to see his cow and as he talked he held her lip tenderly and sweetly between the fingers of his hand. ‘She is a lovely creature, isn’t she?’ he said.

Such gentleness and such intimacy in a world where violence seems as natural as the blossom on a springtime tree. If Homer made the Iliad from such a row, he also knew that there is no boundary between violence and love, that the two coexist in the same hand, the same face, the same slip of contested territory. It is not that these valleys are particularly violent places; only that in such a deeply corrupt society, with government ministers and officials siphoning off subsidies meant for farmers, dodgy bank deals, the abuse of power by local bigwigs, magistrates, the police and even the postmen, all living in a culture of mutual scavenging, taking whatever their power will allow them to take, violence is the resort of the dispossessed. That is true whether it is the bear threatened in his diminishing forest or the poor marginal farmers for whom flat and fertile land at the foot of the valley looks like a paradise of riches. Was it so inconceivable, in this place high up in the valley of Tătarului, that you might attack and kill another man you hated because he owned something which you thought was yours? Would you not feel justified in killing him because his ownership of that land itself felt like a kind of murder? It is a logic of claim and revenge that Achilles would have understood. It is what happens in a place where revenge is the only justice.

Photography © Gus Palmer