Monsieur Austeur is seated in his smoking room, puffing on his silky long cigars. Monsieur Austeur is the master of the house. It’s midnight and everyone is asleep. At the heart of the house, he sits up late. The throbbing of the sleeping house travels out from him, and to him it returns. The signals he emits are slow and steady; those he receives back – from the governesses and Madame Austeur, who’s tossing and turning on her pillow, from the little boys sleeping like logs and the young maids yawning and thinking about their sweethearts – stream in, brief and chaotic, from every corner of the house.

Ensconced in his armchair at the centre of the room, he receives all these cries, these chirrups and yelps from the women and children of the house, and, shuffling them together in his heart, sends them back transformed, slow and steady like the signals from a lighthouse. Once he has done this, the governesses settle down in their beds, Madame Austeur falls asleep at last, the little boys begin dreaming and the young maids can rest easy with a smile.

Monsieur Austeur’s task is not a simple one. He’s obliged to sit up late to keep order in the house: otherwise, danger threatens – the walls would crumble and the windows fly open with a bang. If he wasn’t there watching over the heart of the house like a grandfather clock, who knows what would happen. The governesses would appear out of nowhere in their yellow dresses, panting for breath, the maids would start howling, the little boys would fling themselves out of the windows and the ever so respectable Madame Austeur would rip open her grey dress and expose her skinny body naked on the porch, laughing like a madwoman, a wicked witch.

So he has to be there at night, regulating the breathing of the household with his heart, and, with his solitude held firmly in place by his large square armchair, counter-balancing the chaos that streams in from the bedrooms, prowls on the landings, pokes its nose out from under the doors.

When they hired the governesses the house had been peaceful. A bit too peaceful, perhaps. In those days, he didn’t sit up late, for there was no need to. At night, he would climb into the straitjacket of his square white bed and, in a kind of rage, try to get some sleep. He felt fretful, but didn’t know why. He would press against his wife’s pale body, derive little comfort from it and, in spite of the love he gave Madame Austeur, would feel his manhood unused.

It was chaos he needed. He was there to govern opposing forces, to conjure up sweet sounds and muffle shrill ones, to lead the orchestra with his baton, to blow on the embers and put out fires, to dispel darkness and raise the sun. Instead, here he was with a Madame Austeur who’d become an open book to him, obedient to his dreams, leaving him with nothing further to desire.

The day the governesses walked into the garden, Monsieur Austeur was standing behind the net curtains in the salon, keeping an eye out for their arrival. They advanced in single file: first Inès in a red dress, weighed down with hat-boxes and bags, then Laura in a blue skirt, and, bringing up the rear, Eléonore, who was waving a long riding crop over the heads of a gaggle of little boys. He was amazed: it was life itself advancing. He rubbed his hands together and began jumping up and down in the salon. Into the garden they came, and with them a whole bundle of memories and desires, a throng of unfamiliar faces clutching at their dreams, their future children, their future sweethearts, the interminable cohort of their ancestors, the books they had read, the scents of flowers they had smelled, their blond legs and ankle boots, their gleaming teeth.

By noon, Monsieur Austeur had turned back into a man, and the house once more had a centre – wherever Monsieur Austeur happened to be located. Each time he visited the greenhouse, strolled through the garden or went to inspect the orchard, the centre of the house was there, standing meekly at his side. From the greenhouse or the garden path or the orchard he would share out, generously and fairly, the steady beatings of his heart. Around him concentric circles would form, radiating out to the far edges of his life. That’s what living was.

For the governesses, moving in with Monsieur and Madame Austeur was like a homecoming. Whenever they lost their way in their new garden, all they had to do was climb into a tree and look for the smoke from Monsieur Austeur’s cigar: as soon as they saw it drifting gently between the leaves they knew exactly where they stood in the maze of their new life.

Where were they from? It’s hard to say. But it’s safe to assume that, in spite of their young age, they had experienced some sort of tragedy in their life, at least one. What leads one to believe this is their eccentricity: too much joy, too much grief, too much appetite, too much silence, a strange frenzy.

It’s obvious there’s a secret in their past. Nothing out of the ordinary perhaps, but something that has moulded their character and shaped the way they move, the sound of their voices, their dreams, their habit of roaming around the garden with their hands pressed to their temples. The presence of that secret somewhere between the heart and the womb could also be said to have deprived them of free will, but then who can be said to possess free will? The governesses are like those clockwork toys that start walking when you wind a key in their back. Each morning, a key turns in their slim, aristocratic backs, and away they go, clapping their hands, rolling hoops, devouring strangers, spinning round, three little turns, each faster than the last. Every evening, they come home tired and a little more gentle. It’s at times like these that you can talk to them and be heard. For a few hours, the machinery has wound down. At times like these they don’t understand a thing about their gargantuan appetite. It horrifies and shames them. At times like these, they dream of being someone else and think it possible. They’d just need to jump around less, wear pale dresses perhaps, and change hairstyles. They vow to imitate Madame Austeur, to go out with her tomorrow gossiping about womanish things as they saunter past the clipped rose-bushes, gathering up the wilted petals. Yet when tomorrow comes, they leap out of bed with a wicked gleam in their eye, grab their red dresses, break a window, lash out at the maids, run over to the gates, race across the lawns, sense an unfamiliar form hiding behind a dark tree, go over and start to pursue him, get dirty and tear their clothes.

Keeping a close watch on all this unruliness is Monsieur Austeur. He no more knows what he’s doing than the governesses do, but he reins them in, so that everything is once more orderly, composed.

Every once in a while, they pretend to leave. Just to stir up the household, which, in spite of the governesses’ outlandish behaviour, is almost Apollonian in its staidness. It’s also an opportunity to see Madame Austeur cry and Monsieur Austeur looking bewildered, which excites them no end.

Whenever they pretend to leave, they play their parts so well that everyone is taken in by their little game, including themselves. Even though they’ve played it a dozen times before, each time the result exceeds everyone’s expectations: maximum distress, weeping and wailing, shame-faced confessions, shudders, a clean sweep of the past.

They begin by packing their bags with gritted teeth. Tipped off by the maids, Madame Austeur rushes upstairs, a handkerchief clutched to her trembling mouth. The governesses don’t look up. With a bashful air, wringing her hands, Madame Austeur asks them the reason for this headlong departure. They turn icy gazes on her. Their despair is patent.

Carrying hat-boxes and bags and wrapped in their travelling cloaks, they descend the stairs, always in single file, their minds made up. Monsieur Austeur comes out of the smoking room and tries to intervene. They march straight past him and arrive at the front door. He flings himself in the way, blocking their path. Without a word, they push past him onto the porch. He rushes down the steps and again blocks their way, pleading with outstretched arms. Again they push past him. He then jogs along behind them as they stride on ahead, their outraged faces staring up at the sky, the flesh of the iris inflamed, legs steady, backs arched. A horde of dismayed little boys has gathered round and accompanies them.

When the gates are in sight they slow their pace. It’s barely noticeable, but the moment they do so Monsieur Austeur straightens up and heaves a discreet sigh of relief. They’re strutting around now, swinging their hips, chatting among themselves and shaking out their hair. They sit down by the edge of the path; they need ‘a little breather’, they say. The fact that they’re speaking means that the worst is over. Monsieur Austeur draws himself up to his full height, smooths his hair, straightens his jacket and casts an eye around the gardens. Back in the house, just visible behind the net curtains, Madame Austeur has sat down at last. The elderly gentleman has put down his telescope and is rubbing his hands, laughing quietly to himself.

They don’t surrender their ground just yet. Instead, they wander nonchalantly over to the gates and poke their heads between the bars. Monsieur Austeur observes their every movement. The little boys have gathered round him in a semicircle. The governesses take a step forward, then a step to the side. Then, as though propelled by some mysterious resolve, they wheel round, push their way through the crowd and march back up the path. The danger has passed. For the next week or so, they’ll be treated like queens. Their every whim will be catered to. At a glance from one of them, Madame Austeur will rush upstairs to fetch something or Monsieur Austeur go out in the rain to look for a hoop that’s gone missing. The little boys will know all their lessons by heart. The young maids will pin photos of the governesses above their beds.

And at night, when they go into the garden, the eyes trained on them from behind the windows and the glint from the telescope following them into the brushwood will give them the feeling they’re cherished and loved and no longer alone in the world, and that in this huge dark garden with its enormous trees, they’re protected, even when they’re lost in the darkest undergrowth.

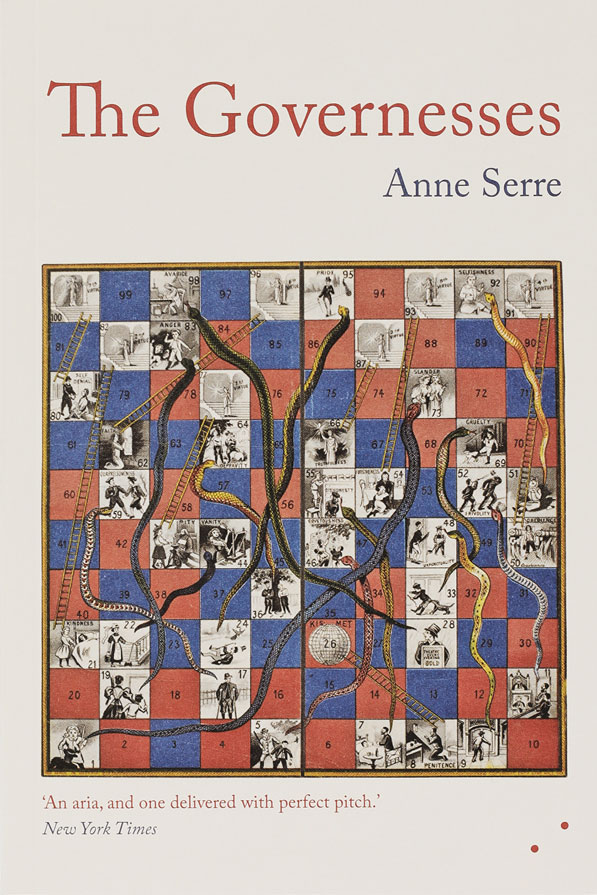

The above is an excerpt from The Governesses by Anne Serre, translated by Mark Hutchinson and published in the UK by Les Fugitives on 2 April 2019.

Photograph © Taz