I can see now where this story ended, although for a long time I was playing with other endings, reluctant to let go. It ended with that moment of cinema, crossing General Stroessner’s spongy lawn and looking back to see him, framed in the doorway, waving. I waved, went through the gate and into the General’s car, and the world rushed in around me, hotels, luggage and airports – everyday people, everyday lives.

I didn’t go back – that was one possible ending, that I would return. I told myself there was no time and it was true. But the story wouldn’t go away. The kitchen telephone would ring and it would be Gustavo Stroessner, the General’s son, bellowing in that strange accent down a fuzzy line from Brazil, like an unruly fictional character nagging for a larger part in the plot.

‘Hello, Colonel. How are you? How is the General?’

‘Do you need any material?’ he would answer. ‘How is the work going?’ None of the ‘material’ ever arrived, but it didn’t matter. I knew what it would have been and was glad he hadn’t sent it.

But where had the story begun? It had been there for years, but I always found something else – wars, elections; Latin America was never short of events clamouring for attention. Except in Paraguay. Paraguay was a situation, rather than an event. It was wrapped in a layer of clichés, and, when events poked through, they seemed only to reinforce the clichés. Josef Mengele was in Paraguay; fascist army officers from Argentina fled to Paraguay when their coup plots failed; Indians in the Paraguayan jungle were hunted by fundamentalist American missionaries with rifles. Stroessner had been there for ever and always would be.

Then, suddenly, in February 1989, he wasn’t.

I wasn’t there either. I was in Jamaica, watching a more orderly change of government. I called my newspaper from Kingston, cursing my bad luck – a journalist in the wrong place. It was too late. Stroessner had been hustled out of the country and had gone to ground in Brazil, where he sat in his beach-house, under siege from a press corps in bathing suits. No interviews, no comment, no recriminations. Nothing.

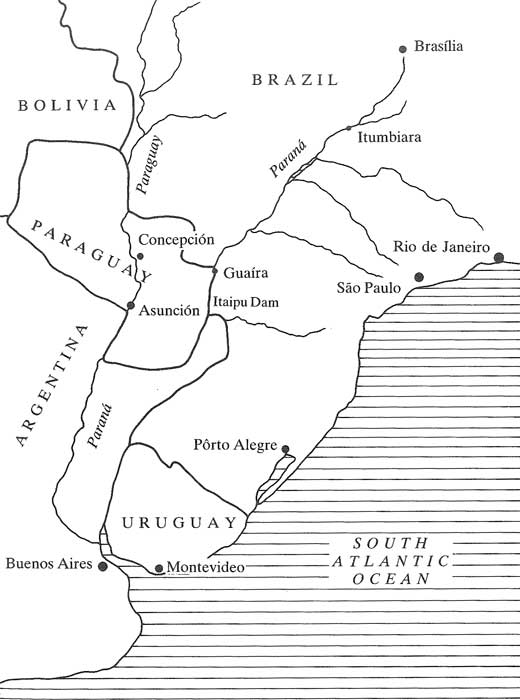

General Alfredo Stroessner with his wife Dona Eligia at a mass celebrating the independence of Paraguay, 14 May 1986.

He had never been a great one for interviews, but now he had a further excuse. He was in asylum and that imposed silence. After an interlude of disorderly scenes at the beach-house – photographers on stepladders peeping over the wall, helicopters chartered by TV companies chattering overhead – he was moved. Some said to São Paulo; others said Brasília. At any rate, he had vanished behind another set of walls, another set of guards. He was rumoured to be ill and had a brief spell in hospital, then silence.

Six months later, I decided I would try to find him, to talk to him, and I had mixed feelings about the prospect. I knew nobody had and I didn’t really see why I should be different, though I also knew that the unpredictability of Latin America could precipitate you as easily into a president’s office as into a jail. I had set out on similar quests before and knew that they followed no timetable and that you just had to go where they led you until you either gave up or found yourself pushing an open door. I also knew that the last door always opened on to another, that it was hard to stop going through them and that there was never going to be enough time; I would end up, I feared, with one of those hollow-hearted stories that reconstructs the drama without the main character.

But even with that risk, it was a tempting drama. I knew that Stroessner’s Paraguay had featured a kind of rampant official gangsterism, racketeers masquerading as high officials, contraband pretending to be business. There was a constitution, a state structure; there were laws, elections: but none of them were real. What was real was power, cronyism, corruption, the righteous men in jail and the criminals in government. At least, that’s what I had been told. I didn’t doubt it, exactly, but I hankered, foolishly, for evidence. I wanted to meet someone who had been cheated and robbed; I wanted to know exactly who had done it. I wanted to follow a thread to the Presidential Palace.

I set off for Asunción at the beginning of September 1989 with a suitcase of research I had only just begun to read and a list of names and numbers. Apart from one detailed academic political study and some slim volumes published by human rights organizations, there was remarkably little about Stroessner’s Paraguay. It was, as someone was to say, in the et ceteras in the list of nations. It was like the silent planet, on a different radio frequency from the outside world. It fought savage wars with its neighbours, in which thousands died; created passionate myths and legends, but who cared? It changed presidents so often that when Alfredo Stroessner staged his coup, in May 1954, then sanctified his newly acquired throne with rigged elections, he must have seemed like just the latest man through the revolving door.

When he fell, thirty-five years later, he held a number of records. He was the longest-serving dictator in the western hemisphere and the second longest in the world: only Kim Il Sung outlasted him. The world had lived through thirty-five years of history, but three-quarters of the population of Paraguay had known no other leader, and there was not an institution or political party in the country that had not been shaped by his presence.

I had read that his image and name were everywhere. A neon sign flashed the message in the Plaza de los Heroes in Asunción: ‘Stroessner… Peace… Work… Well-being’ – on, off; on, off; on, off; twenty-four hours a day. Television began and ended with his heavy features and a march named after him. There was a Stroessner Polka, for more light-hearted occasions. The airport was named after him. The free-port on the Brazilian frontier was called Puerto Stroessner. There were Stroessner statues, avenues and roads, and official portraits of him hung in every office and school.

When I got to Paraguay, six months after he fell, he had been painted over. The portraits had gone, the airport was renamed, the march was no longer played and some of the statues, at least, had disappeared.

Democratic ideals were now the height of fashion. General Andres Rodriguez – who had led the February coup against Stroessner, his old friend, mentor and relative by marriage – had sanctified his position, like Stroessner, with electoral holy water: he got 74 per cent of the votes. Everybody knew there had been fraud, out of habit, if nothing else, but since Stroessner used to get over 90 per cent, Rodriguez looked like an honest man. Many people, I was to discover, liked to think that Rodriguez’s less than perfect elections were free and fair. There had been something so grubby and humiliating in the last years, to be living in Stroessner’s Paraguay, that people fell upon the idea that this was now democracy and used it to wash away some of the slime. So large had the tyrant loomed that it only required his removal to encourage the hope that democracy was possible. From there it was a short step to pretending it had arrived.

Rodriguez was immensely popular. He was cheerful, where Stroessner had been bad-tempered; vigorous, where Stroessner had been in decline; available, where Stroessner had been withdrawn. Rodriguez never troubled to hide the fact that he had grown immensely rich in Stroessner’s service but he had been forgiven his sins for this one act of deliverance. Only a few, with a natural bent towards scepticism, reflected that in May 1954 it had seemed like a new dawn too.

I was shown to a room in the Hotel Excelsior, proprietor Nicolas Bo, friend of General Stroessner. It was pitch-dark.

Was there another one? I asked.

Yes, but a room with daylight is extra.

I paid extra and got a view of a huge building site across the road. Every morning, at seven, I would be woken by the clink-clink of hammers on concrete. While I was there, the building rose a whole floor. I used to look out of my window, wondering who was out there in the city who could help me and what I had to do to find them.

It was Saturday when I arrived, the traveller’s dread weekend. I looked through my list of names and numbers. The shops were shut, the town was quiet, the phones didn’t answer. I began to read again, trying to absorb the country’s tortured history.

Asunción – still sleepy, but sleepier then. When Stroessner came to power, only one square kilometre of Asunción had running water. The rich lived in colonnaded houses along Avenida Mariscal Lopez, rattan chairs set out on deep verandas. Water and milk were sold off mule-carts, and the life of the town centred round the railway station where the peasants came in from the country to sell vegetables and chickens.

Outside the capital, red dirt roads turned to mud in the tropical rains. The wars that had kept the country backward had affected its society too. In Bolivia or Peru, there were enough of the Spanish-speaking élite to colonize, to relegate the Indian population to a despised under-class. In Paraguay, although tribal Indians were being steadily exterminated, their culture had always been accommodated in the past, even absorbed. The indigenous language, Guarani, is as important as Spanish, spoken by every populist politician. And, in spite of the strength of the Church, the need to repopulate the country after the worst of the nineteenth-century wars had left a legacy of de facto polygamy.

I would get to know Asunción a little, peeling back its layers of history: single-storey homes and grid-patterned streets running down the hill to the river; flashy high-rise buildings in the centre and, scattered through the outskirts, some giant institutional relics of a building boom in the late 1970s. Nobody had been very interested in roads or drains, it seemed. The streets were full of potholes, and had been scoured and carved up by the tropical floods that coursed down them. A few ostentatious hotels, decor somewhere between an ersatz gentleman’s club and a high-class brothel. On the shores of the river, there were the shanty towns, squalid, but not as many as in Lima or Rio de Janeiro.

It was a quiet town, still. It woke up at six in the morning and went home at noon for lunch and a long siesta. At five, business started again and by seven or eight it was all over: the rich went to their dinner parties and cocktails; the poor hung about under street lamps, where there were any; the modestly comfortable listened to lyrical Paraguayan music in bars. They sang in Guarani, because, they said, it was more expressive and passionate than Spanish. There was very little crime on the streets – less than the crime in the police or the government. Women sold their babies to foreigners who favoured Paraguay because the babies were less likely to be black than in Brazil; and they sold themselves in several well-known sites around town. On Sundays, everyone went to mass.

I bought all the newspapers. There seemed to be several free shows in town: political rallies at which factions of factions of parties attacked each other before thin crowds; the law courts where a succession of fallen grandees of the Stronato, Stroessner’s system, bandits all, appeared in court protesting their innocence against charges of grand larceny. One general, who swore he never stole a centavo, nevertheless offered, as a gesture of solidarity to the new government, to donate – on a purely voluntary basis – one million dollars to the public purse. Many of the names in the newspapers were familiar from the books I had read: those who had jumped early enough and were still cruising town in their chauffeur-driven cars, still making deals; and those, the famous figures from the opposition, who had been jailed or exiled, and who were now in Congress, making politics.

The weekend wore on in the half-life of the hotel. On Sunday, a telephone number finally answered – some friends of friends, intellectuals. We had lunch and talked about Stroessner. They were not the sort who knew him or wanted to. They had tried to live their lives in spite of him, to create a cultural island in a bandit state. Did I realize, they said, that in thirty-five years Stroessner had never thought of building a national museum or a gallery? Sitting in their house, listening to music, I picked up the telephone book and looked up Stroessner, Alfredo. He was there, followed by ‘Stroessner, Frederico’ and ‘Stroessner, Graciella’, all with numbers and addresses. I imagined a citizen ringing the president to complain about the drains.

On Monday morning, I started in earnest down my list – politicians, journalists, other people’s contacts. Talking to people who hated him would be easy, I thought. Talking to those who had been close was the challenge. Of those, Conrado Pappalardo’s name stood out.

2

Conrado Pappalardo, a friend had told me, knew everything. He had been Stroessner’s political intimate and presidential secretary for years. Pappalardo was also a survivor. He had switched sides at the eleventh hour; he remains presidential secretary, now to President Rodriguez.

The presidential palace lies down near the river, a low, grey building that could never quite make up its mind which architectural style it was imitating: Greek classical? Colonial? Was that square tower English? There were palm trees and dark-suited security men, immobile, their hands hanging by their sides or clasped behind their backs: whatever way I approached the presidential palace, I had to pass one of them.

It was very early in the morning, but there was already a gathering at the door: television and radio reporters; rural officials; the claque of the local press.

To get to Pappalardo, I had first to make a courtesy call on the press office, where I found Oscar, the presidential press officer.

Oscar used to be on television, but this was much better. He was very proud to be serving democracy. No, he had no material about Stroessner, but as many copies as I liked of General Rodriguez’s speeches.

I took a copy, and thanked him. A photograph of President Rodriguez hung behind his desk. I asked him what had happened to the thousands of portraits of President Stroessner.

He didn’t know, he said.

Along the corridor from Oscar’s office, near the main entrance and overlooking the river, was a vast salon where petitioners sat, waiting for an audience with the president. Whether that audience was granted depended on the decisions taken in the last room between them and the inner sanctum, Conrado Pappalardo’s office, where power was discreetly, but enduringly, exercised.

Pappalardo was smooth, rich and elegantly dressed; his manners were impeccable; he was the perfect servant. Someone told me that, as well as having once been Stroessner’s secretary, Pappalardo was also Stroessner’s godson. Stroessner, patriarch of the nation, had many godsons.

I made my speech of introduction and dropped a name, the son of a former Argentine ambassador who had known Pappalardo quite well. Pappalardo made careful note on a piece of presidential notepaper, under my name. He checked, several times, that he had spelled it correctly, then asked a few questions to determine how seriously he should treat the name-drop.

Pappalardo viewed Stroessner with affection and with sadness, the sadness of having watched his greatness decline into the foolishness of a sclerotic old age. He had been a great governor, Pappalardo told me, who had raised the people’s living standards and insisted on raising educational levels to those of Italy. ‘So obviously, once that happened,’ Pappalardo said, ‘the people wanted more liberty and Stroessner didn’t want to give it. Until 1982, I was behind him. He was always polite, never angry, never irritated.’ But in 1982, Pappalardo sighed, something went wrong. ‘He seemed to grow bored, and the militants took over the government. His son, Gustavo, began to emerge. He spoke badly of his father, disloyally.

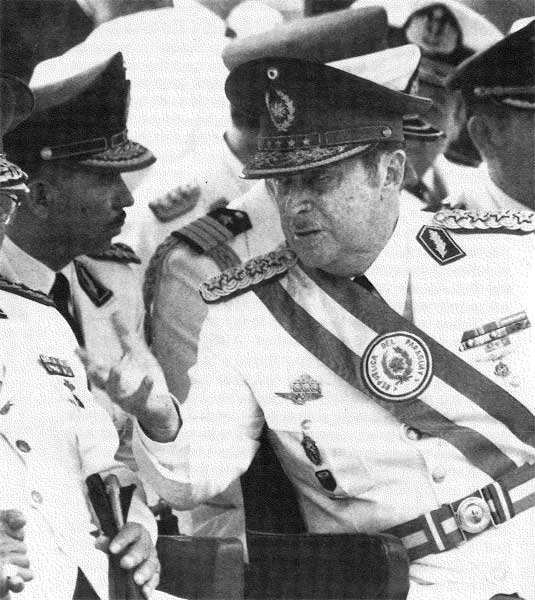

General Alfredo Stroessner wearing a poncho given to him at an inauguration parade in June 1959.

‘Gustavo was always complaining,’ Pappalardo added. ‘He complained that there were women and children everywhere.’ I had heard that that Gustavo, the heir apparent, and Pappalardo, the godson, didn’t get on, that they were jealous of each other.

I had also heard that it was Pappalardo who managed the payroll for Stroessner’s many mistresses, distributing the money on Fridays.

Was it true, I wondered? Stroessner acknowledged his children, didn’t he?

Pappalardo frowned and sucked his teeth for an instant. ‘No… He neither denied them nor acknowledged them.’ Pappalardo started describing how Stroessner lived – ‘like a soldier, you know, a very spartan life. For years there was no hot water system in that house. He had one of those little showers that heated the water when you needed it.’ We talked about Stroessner’s house and Stroessner’s marriage: he never paid much attention to his wife, Dona Eligia. ‘He lives alone now,’ said Pappalardo. ‘Perhaps he’s too proud to call his wife to ask her to join him.’

It was really only power, Pappalardo added, that interested Stroessner.

There was a red telephone on Pappalardo’s desk, the presidential line. It rang and Pappalardo jumped. It was not a jump that implied any fear on his part, but rather a demonstration of his own importance and his gift for perfect service. When the president needed him, he must attend.

‘Immediately,’ he said into the telephone and left the room. People started entering his office, gossiping, waiting for a good moment to whisper a request to the fixer of fixers. Outside, in the public salon, more people gathered; I could hear the shuffling of their feet to mark the passing time. Pappalardo returned and continued his story, from time to time interrupted by his other duties, in and out of the president’s office.

He himself had realized, Pappalardo said, that the old man had to go, and he told him so in 1982. ‘Stroessner didn’t reply, but he never really spoke to me after that. I offered him my resignation every year, but he never accepted it.’

What could the perfect servant do, but carry on?

But things had changed, he said. Stroessner became remote and lost his concentration. The government was run by low-grade advisors and scheming ministers. ‘Stroessner spent only one hour here each day and he spent the rest of the time at home, reading. Nobody knew because everybody was so loyal to him that it was hushed up.’

Pappalardo mentioned other personal titbits. Stroessner, who was afraid of illness, cultivated the myth that he had perfect health. Once, said Pappalardo, he had an operation for skin cancer and refused an anaesthetic, preferring pain to the impotence of unconsciousness. Stroessner hated being touched, Pappalardo told me, and never embraced anybody. He never threatened or lost his temper, but then I doubted that Pappalardo had ever given him the chance.

Pappalardo was coming to the end of what he wanted to tell me. He gave me a copy of General Rodriguez’s speeches. ‘This will be of great interest to you,’ he said.

I hid Oscar’s copy under my handbag and said thank you.

I asked him if I could see Stroessner’s house.

That, he said, would be difficult.

I asked him if I could see Stroessner.

He smiled. He had no contact and could not tell me who might have.

I asked if I could see those former ministers who were now in jail.

That, he said, would be up to the Ministry of Justice but he thought it would not be possible.

I knew I was becoming a nuisance and in danger of being dismissed. Then the door opened and a man came into the office. Pappalardo saw his opportunity. ‘This is the man you should talk to,’ he said. ‘Ambassador to the Presidency, Miguel Angel Gonzalez Casabianca. This is the new Paraguay,’ Pappalardo said, in the manner of a Harley Street gynaecologist modestly displaying the healthy outcome of a rather difficult breech presentation. ‘Dr Casabianca was in exile for many years and now he is part of the government. You should get to know him. He could become president.’

The Ambassador to the Presidency made a face and sat down heavily at the table, pulling out a packet of cigarettes.

Dr Casabianca was a tall man with a large, heavy face, drooping eyes, the creased skin of a chain-smoker. He had a gloomy watchful air that I later decided resulted from having subordinated most other things in life to a political struggle that must have seemed, for most of that time, hopeless. I waited, not yet knowing where Casabianca fitted so not sure where to begin.

The door opened again, and a delegation of local party bosses shuffled into the office. They had come to invite the president to their folk festival. They were small, dark and weather-beaten, dressed in the dateless style of the South American cowboy. They would have figured as fittingly in a 1911 daguerreotype as in a street-corner band. Pappalardo stood up and received them graciously, paying elaborate tribute to the beauties of their town.

Pappalardo returned for a moment and I tried my luck with one more direct question: were the stories of Stroessner’s promiscuity true?

Pappalardo answered. There was more to it than showed in public, he conceded. ‘Never in public and never orgies.’ And then he deftly shifted the subject again. ‘But he talked very little about his personal life… He was never concerned about his children. He was only interested in power,’ he repeated. ‘He wasn’t,’ added the man who had served Stroessner for more than thirty years, ‘all bad. Whenever a Paraguayan drives on a paved road or comes into that airport, or switches on a light, they should be grateful to him. Yes there was contraband… But people here don’t think of that as a crime. If you brought the Queen of England to Paraguay she would run contraband too. Up to 1982 he was a good president, but then he began to weaken.’

A bugle sounded outside his office, and there was a rush of footsteps. The president was leaving the palace. Pappalardo swept up his briefcase and glided definitively out of the room. The palace had emptied as if by magic. It was like a stage set after the show was over.

It rained most of the day, a chilly rain, and in the evening I met up again with Dr Casabianca at a German bierkeller. Casabianca drank whisky, chain-smoked Kents and talked about the years of hopeless exile politics, watching twenty-five years of life slip by and the dictatorship remain as firm as ever.

While Pappalardo had been oiling the wheels of the Stroessner machine – ‘He’s a hard man for a government to do without,’ Casabianca had said earlier, smiling one of those private, exile’s smiles, ‘so many years here, helping everybody’ – Casabianca had been one of those whom the machine had all but crushed.

And how had that machine been made?

Before Stroessner came to power, there had been eleven presidents in nineteen years – Stroessner had conspired against five of them – and if there was a lesson in Paraguay’s bloody history it was that weakness was the only political crime. Since the late nineteenth century, few Paraguayan presidents had had more than a few months in office, a year or two at most. Stroessner set out to be different.

There were two potential pillars of power in Paraguay – the army and the right-wing Colorado Party – and it was Stroessner’s trick to use each to dominate and control the other. Stroessner became president as the Colorado Party’s candidate – he was already commander-in-chief of the army and he then consolidated the army’s obedience by making membership in the Colorado Party compulsory for all officers. But the party was the problem: the only reason he had been nominated was because the members of each one of several factions thought they could use Stroessner to destroy the others.

In the first few years, Stroessner set out to purge the party, helped by a young member of it, Edgar Ynsfran. Edgar Ynsfran later became first his chief of police and then his minister of the interior. Ynsfran, supported by a network of informers, turned out to be ruthless. The year after Stroessner was elected he created the legal instrument Ynsfran needed – the ‘Law for the Defence of Democracy’, under which opposition activity was labelled Communist. Stroessner also continued the state of martial law, which suspended all constitutional guarantees and allowed Ynsfran’s police to detain and torture whomsoever they chose. Martial law had been in force since 1929.

By the late fifties, however, Stroessner’s greatest challenge came from yet another faction in the Colorado Party, whose members wanted an end to the police state and demanded political normalization. Casabianca was among them. He had been a student leader and then a congressional deputy and had supported demands for political reform – an amnesty, a new electoral law, press freedom. The leadership of the Colorado Party then backed the demands as well, and Stroessner appeared to agree.

Shortly afterwards there was a student demonstration, and Stroessner took advantage of it to throw everything into reverse. The demonstration was violently repressed and turned into a pitched battle between students and police. When Congress complained, Stroessner dissolved Congress. A reign of terror began. The state of siege, which had been briefly lifted, was reimposed, and a vast round-up, masterminded by Ynsfran, began. Over 400 Colorado politicians who opposed Stroessner were jailed or fled into exile, where they founded the Popular Colorado Movement.

With the crackdown Casabianca went into hiding in the Uruguayan embassy in Asunción. Six months later he left the country. He had always been one of Stroessner’s favourites, but thereafter Stroessner persecuted Casabianca wherever he went. ‘Stroessner was always very indulgent but finally he would never forgive you if he thought you had betrayed him.’ He had a long arm, Casabianca said, and a long memory. Casabianca scraped a living in Buenos Aires, working in the central market, eventually working his way up to be supervisor of supplies to the city’s markets. But then, following the coup in Argentina in 1976, Casabianca was suddenly thrown out of his job again. ‘After that, I did whatever I could, buying and selling, an estate agent for a while. Now here I am, working alongside the people responsible for all those years of persecution.’

Casabianca is a public figure now. He has a huge office in the presidential palace and is greeted with respect in restaurants. He drank several more whiskies and sent the coffee back, complaining it was cold. ‘All the waiters here used to be police informers. Now some of them work with us. Now all my friends who weren’t around all those years are reappearing. Still, you can’t blame people for that. The consequences are too serious here.’

Driving home, the special ambassador to the presidency fiddled unsuccessfully with the car heater. ‘They just gave me this,’ he said, ‘I still don’t know how it works.’

Argentina’s President Juan Péron is welcomed to Paraguay by General Stroessner in August 1954.

The next morning, I went back to my list of names and numbers. Pappalardo had started as my best hope. Seeing him had left me flat. I needed some allies, some strategic advice. I had the number of a lawyer, Felino Amarillo. I had been told that he would make me laugh and that he could introduce me to the Asunción underworld. I rationalized my need to laugh with the thought that perhaps, if the government wouldn’t help, the gangsters might. I never met them; but I did meet Felino.

After a long telephone chase, he turned up at my hotel, lounging there in one of the pompous leather chairs, a slim young man with his black moustache, looking round a lobby that was overflowing at the time with society women rehearsing for a charity fashion show.

I introduced myself.

‘Why do you stay in this brothel?’ he said.

I rode down to Plaza Independencia on the back of Felino’s newly acquired motorbike. He rode a motorbike, he told me later, because he couldn’t afford a car. At least, he couldn’t afford a legal car. Half the cars in Paraguay were not legal. They had been stolen in Brazil and driven over the border. They are called mau cars, because, like the Mau-mau, they came in the night. It was one of the army’s sidelines.

Why didn’t he buy one of those?

He gave me a pained look. ‘In the first place, I wouldn’t buy a mau car. And in the second place, as soon as someone like me did buy a mau car, the police would come and arrest him for having it. You can only drive a stolen car if you are in the police or if you’re a friend of a policeman.’

We took the lift to the fifth floor. Someone had scratched the name Felino Amarillo in the paintwork. ‘Young people,’ Felino observed. ‘No standards.’

‘Hey, Gordo! [Fatso!]’ he yelled, when we got into his office. There was a groan next door. ‘Stop sleeping and come here!’

A man appeared, rubbing his face. ‘I wasn’t sleeping, I was reading.’

Felino bellowed with laughter. ‘May I present Dr Rafael Saguier. Rafa, this distinguished English journalist wants to know about Stroessner.’

‘La puta madre,’ said Dr Rafael Saguier.

‘Scottish journalist,’ I said.

‘Make yourself at home,’ said Rafael. ‘Stroessner. La puta madre. We must take her to the escribano.’

I never quite understood why I had to see the escribano, except that he was considered to be both wise and knowledgeable. For Rafael and Felino it was clearly imperative, in any case, that I did, so I found myself out in the street again, dodging along the narrow pavements, Rafael on one side and Felino on the other, both talking at me, shouting scurrilous Stroessner anecdotes over the roar of the traffic.

It was my turn to be self-conscious. I kept my eyes front, wondering who was watching, who could have seen from a passing car. It was a feeling that I was to have often. Asunción was a small town in which everybody knew everybody. Every time I talked to someone, I wondered who would find out about it, what they would hear. I felt no closer to finding Stroessner, but there was the sense that behind one of those windows there might be people who could, if they chose to, if I could convince them, open the door.

We got to the escribano’s office. He sat under a slowly revolving fan in a room shuttered against the sun. ‘In Paraguay,’ he said, ‘the usual gap between the Third World and the developed world is even greater. So what is the aim of ideology? In the underdeveloped world ideology is a system of lies which stimulates people to survive. Truth and science are the monopoly of the developed world. Stroessner was thirty-five years of no truth and no science.’

3

Back in his office, Felino said, ‘I’m going to lend you, lend you mind, a real treasure.’

He reappeared a few minutes later with a book. He was hugging himself with glee. He read out the title, The Golden Book of the Second Reconstruction, and fell back in his chair, bellowing with laughter. For the Stronato historians, Felino explained, the first ‘reconstruction’ was that of Bernardino Caballero, a nineteenth-century tyrant who fathered over ninety children and, at the end of his reign, left the country with sound finances, a trick rarely repeated in Paraguayan history. The second ‘reconstruction’ was Stroessner’s. And it was this that The Golden Book described.

The prose of The Golden Book strains against the outer limits of adulation. When mere words are inadequate to describe the greatness of Stroessner, a common failing apparently, the very type is forced to unnatural extremes. Felino began to read:

We have seen Alfredo Stroessner, THE LUMINOUS LIGHTHOUSE, in his various facets dissipating the shadows of PARAGUAYAN NIGHT. We have not been able to embrace the totality of his life because that would be a labour requiring more breath than we have… We will not enter into an analysis of whether he had or has defects. It is human to have them in the midst of the great virtues which he possesses. But, yes, we consign to you what he once said: ‘One cannot be perfect because perfection belongs only to God, but we must try, as far as possible, to reach a degree of perfectibilty which will take us closer to God.’

‘What’s the book about?’ said Felino. ‘What’s anything about in this country: money and corruption.’ Felino showed me the back pages, which were advertisements, the paid and signed subscriptions to the cult of the dictator: ‘– –– would like to congratulate the author on his luminous work of history… ‘ ‘– ––, patriot and outstanding citizen, salutes President Stroessner.’

‘Outstanding citizen,’ snorted Felino, ‘he paid to have that advertisement put in. About himself!’

‘Look at this one,’ Felino said, flipping through the pages, pointing to another advertisement: ‘Obra util. Useful book: declared such by that minister means that every school then had to buy this useful book.’

I took The Golden Book back to my hotel and continued to read it, wincing with pain. Every page revealed the writer’s effort. There was, for instance, the challenge of turning Stroessner’s unremarkable parentage and early life into the nation’s destiny. This is what I read of the first meeting between Stroessner’s father Hugo, an immigrant German brewer, and the local girl he was to marry:

A fifteen-year-old girl passed [Hugo] one day and powerfully attracted his attention. In romantic terms, he had been struck by an arrow. He united himself with her. It was an instantaneous decision. HERIBERTA MATTIAUDA, thus was the name of the young woman who moved [Hugo’s] most intimate fibres. She was a descendant of a well-known family in the area, and in her were united the features of wit and beauty and the gallantry and the presence that belong to Paraguayan women… Heriberta had once read about Charlemagne in a novel, and her suitor was like a Blue Prince, since his eyes were blue.

I read on, by now enjoying the pain. Two sons and a daughter were born, and briefly mentioned. Then came the birth of Alfredo, whose cries ‘already seemed to announce a new dawn for Paraguay’, and who, in the eyes of his father, ‘had some connection with the product of his labours, seeing him as blond as the liquid product of his noble sacrifices.’ I read the sentence again, in disbelief: Alfredo was as blond as a pint of German beer?

Sadly, the effort of this prose proved too great to sustain, and most of The Golden Book is a tedious transcription of the official diary. Not a ceremony missed, not a decoration unrecorded. There were many ceremonies, an embarrassment of decorations: natural tributes of a world rushing in to honour the greatness of Alfredo Stroessner. For the outside world, Stroessner was not an unwelcome figure. The United States pumped in military and economic aid, and trained the officers of Stroessner’s police and armed forces. He was, after all, a staunch anti-Communist. For the Brazilians he was a loyal friend, stability on their southern flank. For his fellow dictators in the 1970s he was a compadre. The international approval rolled in: Order of Merit of Bernardo O’Higgins, Chile; Order of the Condor of the Andes, Extraordinary Grand Cross, Bolivia; Collar of the Order of the Liberator, Venezuela; Order of Aeronautical Merit, Grand Cross, Venezuela; Grand Cross with Diamonds of the Order of the Sun, Peru; Golden Wings of Uruguay; Honorary Aviator, Chilean Military Medal; and from General Sam Shephard, US Army, the Medal of the Inter-American Junta of Defence. In a lull in the proceedings, he gave himself the Paraguayan Diploma and Brevet of the Naval Pilot.

There was more: the United Arab Republic, Holland and Japan. In 1961, Queen Elizabeth remembered the general and gave him the Order of Victoria (the Caballero Grande, as The Golden Book describes it). Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, followed with the Grand Cross of the Knights of the Order of St Michael and St George in 1962, and General de Gaulle pinned the Legion d’Honneur on to what was, by then, one of the most crowded chests in South America.

I trudged on – past sinister photographs of the members of Stroessner’s cabinets being sworn in with a straight right-arm salute, of a multitude ‘delirious with enthusiasm’ acclaiming its leader at a rally – searching for some coded trace of reality, some acknowledgement that not everyone had applauded. There was none. There was no mention of the opposition, the dissenters – no name was allowed to challenge the omnipresence of Stroessner’s. There were, instead, a number of familiar faces. There was, among them, Conrado Pappalardo in 1969, slimmer and wearing a moustache. ‘State Director of Ceremonial,’ read the caption, ‘a man who, from the first moments was and is at President Stroessner’s side.’ And there was another name, one that ran like a counterpoint through the diary, heading a delegation here, presiding over a ceremony there, leading the applause at meetings, standing in for the absent president when he went abroad. Over and over again, the name of Juan Ramon Chaves.

Juan Ramon Chaves – his nickname, I learned, was Juancito the Liar – was on my list and I had been trying to find him. Juancito was the man who had run the Colorado Party for Stroessner, frightening off the opposition, delivering the renominations, managing the conventions that rewrote the constitution to prolong Stroessner’s rule. Juancito had been president of the party for twenty-five years, Stroessner’s political right arm, until Juancito came out on the wrong side of a party split in August 1987. But when Stroessner was overthrown, Juancito, like Pappalardo, got his old job back. I was told that he was nearly ninety now and was running the party again.

The Colorado Party headquarters is a vast building in the centre of town. Like the Communist Party palaces of Eastern Europe, it is a testament to years of domination and robbery. You approach it up a steep flight of steps from the street and then enter a cavernous hall. Once Stroessner had subdued the internal opposition, the Colorado Party enjoyed huge revenues based on a compulsory subscription from the salaries of all public servants. Everybody had to join, from the humblest army cadet to the beauty queens. It was the patronage machine: local section bosses ruled like petty kings – they enjoyed mbarete, or ‘clout’, and, in return, delivered raised hands at convention time.

Juancito Chaves ran all this, Stroessner’s system, one organized along fascist lines with branches in every village and with a network of paid informers. They reported chance remarks, unwise jokes and, of course, conspiratorial intentions. If the penalties for disloyalty were absolute, the rewards for service were great.

The security apparatus, the adjunct to the party network, consumed 30 per cent of state revenues and was sustained by military aid from the United States and from development aid, some of which also went to build the roads and bridges that Stroessner always pointed to as the emblems of his ‘modernization’ of Paraguay.

In his modernized Paraguay, there was, above all, peace, but it was a peace punctuated with episodes of savage violence directed against peasant organizations, trade unions, the Church or anyone who showed a capacity for organization outside the Colorado Party. The price of peace – a phrase that became part of official terminology – was the division of spoils: monopolies of contraband pacified the military and police – whisky, cigarettes, electronic goods, cars stolen in Brazil – and high officials took a percentage of every government transaction. The Party enjoyed the privileges of the one-party state. And holding it all together, at the centre of the web, the all-pervading image of Stroessner.

He held it all together through fear, but fear was not all. As I talked to people, I realized that Stroessner’s domination was a subtle balancing act between co-option and terror, sometimes within the same individual. Those who served him feared him, but serving him was also the quickest way to get rich. And those who were closest to Stroessner were not serving him out of their fear of him, but because they wished to share a little of the power and a lot of the money. Fear was just what the opportunity cost.

He maintained a cynical show of formal legality. When he needed to reinforce the appearance of democracy, he tempted the opposition into co-operation with the promise of participation, then snatched it away. The constitution was amended twice to allow him a further term in office, in 1967, at a constitutional convention attended by almost all political parties – except, of course, the banned Popular Colorado Movement – and again in 1977, to perpetuate his rule for life. Both these conventions were run for him by Juancito the Liar.

Juancito’s daily routine was a legend in Asunción. He left his house at dawn and got into his car. He appeared briefly at the party headquarters and then returned to his car. From then until evening, he roamed the town. If Juancito didn’t want me to find him, Felino had said, I wouldn’t. The only man in Asunción who knew how to find him was the man who brought him cheese from the market.

I made appointments, but he didn’t keep them. In the end, I just sat, conspicuously, and waited with the others in the huge hall outside his office, under the eye of his door-keepers, watching his machine at work.

A woman began a litany of complaint. ‘They don’t let you see the president. They won’t let you talk to him. They’ll make you wait fifteen days, come back tomorrow, come in the morning, come in the afternoon.’ Barefoot shoeshine boys polished the boots of party members. Others appeared, also barefoot, selling the party paper, Patria, for years the most unconditional supporter of Stroessner: under Stroessner, all public servants used to subscribe; the money was deducted automatically from their pay packets.

Then came the nod.

Juancito’s office was vast. At the far end, crouching next to a bank of telephones behind an immense desk placed beneath an outsized portrait of President Rodriguez, was a shrunken old man. Little Juan the Liar.

‘Well, Señora?’ He rasped out his words. In the pauses, a little lizard tongue flicked across his lips. ‘What do you want, Señora?’

‘To talk about Alfredo Stroessner.’

‘Who?’

I thought perhaps he was hard of hearing. ‘Alfredo Stroessner,’ I repeated, louder.

He waved his hand impatiently. ‘Oh, I can’t talk about that, that’s all past. It’s a local subject, a subject for us.’

‘But you knew him well.’

‘No. I didn’t admire him. I didn’t admire him. I opposed him.’

‘But you were close to him for many years.’

‘No, no, I opposed him. Let’s talk about now, today, about the future.’

He launched into his set-text for foreign journalists – all about the excellent situation of Paraguay now that it had been liberated from the tyranny of Stroessner. Four lines about the economic programme, four lines about the political situation. I dutifully took notes.

‘The situation is good, it’s democratic, without authoritarianism.’

He slowed down, watching my pen move across the paper, making sure that I kept up, that I got it down precisely.

I had expected a defence, a justification of those long years at Stroessner’s side, self-serving but reasoned. An explanation of how, at the end, Stroessner had crossed some final line of tyranny. I was not prepared for his flat denial of involvement.

‘Did you know the coup was coming?’ I asked him.

He waved his hand in a gesture of dismissal. ‘I can’t talk about that. It would take too long. But he didn’t fall by himself, did he? He fell because something happened. But I can’t talk about the past. There is complete freedom of the press here.’ He glared at me myopically. ‘Nobody bothers you, do they? You can come here in absolute freedom, can’t you? Well then.’

The lizard tongue again. The old man’s fidgeting. ‘Stroessner!’ He spat the word out. ‘We didn’t support Stroessner, we struggled against him for years.’ He looked at me, perhaps wondering what I knew. ‘At the beginning, he was a man of much hope. But then he made mistakes and made a bad government.’

‘Which year was that?’ I asked. I knew that Juancito had never defected. He had just been elbowed aside, at the next to last moment, by the new crowd, the militantes.

‘I don’t remember exactly which year it was. We opposed him for many years. The militants had the power. We had none.’

Juancito had been thrown out of the party presidency on 1 August 1987, at a famous party convention. His faction, the traditionalists, had tried to fight off a takeover by the militants, the young Turks who saw their chance to use the last powers of the ageing president to secure the party and the government. They were friends of Stroessner’s son Gustavo, and he, it was said, was their candidate for the throne. The traditionalists lost.

‘But before that you had power,’ I insisted. ‘You were a key man through most of the Stroessner years.’

He spluttered with rage. ‘No, no. It was Stroessner who had power, who had all the judicial and executive power. We didn’t have power. I wasn’t a key man in the Stroessner years. I was a key man in the opposition.’

‘Did you approve of nothing he did then?’ I asked, wondering how far this fantasy would go.

‘A few things perhaps,’ he said. Stroessner had, he acknowledged, built a little. ‘But material things are not the only thing that matter,’ said Juancito. ‘What matters are the spiritual values of democracy, liberty and justice.’ I looked at his huge desk, his bank of phones, trying to find a way through this monstrous lie, some small admission that Juancito might once, perhaps long ago, have supported Stroessner. In the face of this flat contradiction, I would have felt it a victory. But Juancito was a hard man to induce to reflection. His look was growing more venomous. He had begun to chew the air, an old man’s habit. The flunkey was entering the middle distance, headed in my direction. Time was running out.

‘But your photograph is in The Golden Book,’ I said.

‘Golden Book? What Golden Book? No such thing. Never existed.’ And then a thought clearly struck him. ‘You’ve seen it? Which one have you seen… all three?’

‘Yes,’ I lied. Three Golden Books? I hoped I didn’t have to read the other two.

‘You’ve seen all three?’ he said. Now he was thinking, talking fast, wondering whether to make an admission. He didn’t wonder for long. ‘I’m in it, you say? Really? I have never seen it. I didn’t know anything about it. Is my signature there? Do you have it with you?’ I didn’t, and he embarked on his bamboozle-the-jury performance again. ‘Someone must have forged my statement. My photograph? I don’t know anything about photographs. Talk about the future. That’s what matters, not the past.’

He turned the outsized leather swivel-chair towards a phone and picked it up. The grim flunkey gestured me to the door.

‘Well, what did he tell you?’ asked Felino later. ‘He said he was a key man in the opposition,’ I said. I thought Felino would never stop laughing.

In the end, there wasn’t a politician in Paraguay who had not been formed by Stroessner. For those who played the game, there was a seat in Congress and a share of the spoils. For those who didn’t, there was ruin, torture, imprisonment, exile or death. And there were very few who didn’t play the game, at least at first. Talking to people in Paraguay is like peeling an onion. The outer skin is anti-Stroessner. Perhaps the next two layers are layers of persecution. But get to the centre and you will come across a layer of co-operation. Juancito the Liar and Pappalardo are collaborationist onions covered over with the thinnest skin of repudiation. But so many of Paraguay’s famous opposition figures, heroes of the later years of struggle, have, buried inside, that core of collaboration.

Looking through The Golden Book I had found an entry that surprised me: in 1962, it said, President Stroessner inaugurated Radio Nanduti.

I was taken aback. There were two media in Paraguay whose closure had caused an international scandal, and one of them was Radio Nanduti. I remembered running the story at the time, as a short item in the newspaper. It had been a violent affair, in 1986. The military arrived in trucks, shouting, ‘Death to the Communist Jew,’ and sacked the radio station. The sacking was broadcast as it occurred, until the plug was finally pulled.

The ‘Communist Jew’ in question was Humberto Rubin, one of the names that everybody had given me. He was the radio station’s proprietor, chief broadcaster and known as an intelligent and implacable opponent of Stroessner’s. I had planned to see him anyway, but now I wanted to ask him how it was that Stroessner had opened his radio station: just who was Humberto Rubin in 1962?

I was shown into a small shambolic studio where a bearded man with a rumpled face was talking into the microphone. Humberto Rubin seemed to live in the studio, in constant dialogue with his huge audience. The only way to interview him was to be interviewed by him, on air, and squeeze questions into the commercial breaks.

Yes, Rubin said, he had invited Stroessner to open the radio station, not just because he was El Presidente, but because Rubin had believed in him. He had believed in Stroessner first because he was grateful and then because he hoped Stroessner would bring democracy.

‘Look,’ he said, ‘from 1947 until Stroessner came to power it was chaos here, parents against children, brother against brother. When someone arrived saying we were now going to live in peace all of us hoped there would be at least some security. Democracy didn’t even matter that much. All that mattered was that there were no tanks in the street. Until Stroessner came we never knew who had the power.’

Rubin had thought that things would be hard, but that they would get better. ‘The Stroessner chapter was unfortunate,’ Rubin said, ‘but he didn’t create it alone. We all helped.’

Stroessner’s other famous closure was that of ABC Color, the biggest newspaper in Paraguay before it was shut down in 1984. It has an equally famous proprietor and editor, Aldo Zuccolillo. Zuccolillo comes from one of the richest families in the country. His enemies make a point of insisting that Zuccolillo’s family fortune comes from trading in contraband sugar with Paraguay’s old enemy, Bolivia. Zuccolillo’s brother was appointed by Stroessner as ambassador in London – appointed in fact shortly before ABC Color was closed down.

Stroessner closed the paper because it had annoyed him. It had annoyed him because it was publishing about Itaipu.

Itaipu was the most grandiose of many grandiose projects. Its beauty was that it combined several of Stroessner’s fetishes – the friendship with Brazil, a project of pharaonic proportions, electrification and almost unlimited opportunities for corruption.

It was sold as a triumph. The Guaira Falls on the Parana River had been a source of tension between Paraguay, who claimed possession, and Brazil, who occupied them in 1964. In 1966, Stroessner signed the Act of Iguazu with Brazil, agreeing to joint exploitation of the enormous hydroelectric potential of the falls and thus implicitly relinquishing Paraguay’s claim to sole possession. In 1973, with the Treaty of Itaipu, construction of the dam was agreed. It was to be financed by loans raised by Brazil, and Paraguay was to pay off its share by selling back to Brazil, at preferential rates, most of the electricity produced.

Many Paraguayans believed the treaty made Paraguay into a virtual colony of Brazil. Paraguay had little control over the cost of the dam, which rose from the original estimate of 1.8 billion dollars to 17 billion. And in return, Paraguay received only about 15 per cent of the contracts.

But the impact of that 15 per cent on the tiny economy of Paraguay was staggering. The money had never rolled so freely. ‘Before Itaipu, the Paraguayan upper classes’ idea of a good time was to go on a trip to Buenos Aires,’ said Felino. ‘Then they suddenly had so much money they didn’t know what to do with it.’ Asunción became a sybaritic society. Petty officials who had lived in miserable little houses suddenly had two cars and domestic servants and Asunción had more Mercedes than any other capital in Latin America. ‘We were all corrupted,’ said a friend. ‘We all got used to drinking French wine and eating Dutch cheese, to having dishwashers and videos.’ Mass opposition was tranquillized by the flood of money. ‘If Stroessner had retired in 1980,’ said Paul Lewis, author of a study on Stroessner, ‘he would probably have gone down as a great president.’

Paradoxically, for Zuccolillo, Itaipu was a catalyst that forced him into taking up with the opposition and that led to the closure of his newspaper. He told me his story, one that I was finding increasingly familiar: how at first he had supported Stroessner; how, in the late 1960s, that support had become a qualified one, followed by disillusionment and then opposition and finally repression. Even so, ABC Color’s record is one of courage. In the seventeen years the paper published, Zuccolillo’s journalists were jailed on thirty-two occasions. It became the practice for everyone to keep an overnight bag in the office, in case of arrest, and Zuccolillo himself was in jail twice. The end came in March 1984, also a familiar story: fifty police with machine guns, a man with a piece of paper on which was written the charge – promoting hatred among Paraguayans.

Between the closure of ABC Color and the coup, every paper in the country that wasn’t owned by a Stroessner friend or relative was either closed or its staff harassed. The opposition weeklies El Enano, El Radical, Dialogo, La Republica and El Pueblo all went. The staff of Nuestro Tiempo, a church-backed monthly, was persecuted. Radio Caritas, also backed by the Church, tried to fill in some of the space left by Radio Nanduti and was told to stick to prayer.

After the February coup, ABC came back and Zuccolillo had fun exposing the crimes of his fallen adversaries. He published a series of articles on the fabulous mansions built by Stroessner functionaries, and his guided tour – ‘the tour of Asunción’s corruption’, as he calls it – is on the itinerary of every visiting journalist. The tour includes the market, where the contraband ranges from cases of Scotch to plastic buckets from Brazil; the Central Bank building, which contains an Olympic-sized swimming pool and a theatre, true cost unknown; and the mansions of the Stroessner clan, family and mistresses, former ministers and army officers. Zuccolillo’s own home is also a mansion; in fact it is a mansion as large as most of those on his tour, as his wife was the first to point out to me.

The tour also includes General Rodriguez’s French chateau, though that was left out of the newspaper series.

I asked him why.

‘Because of what he did in February,’ he said. ‘I have forgiven all his sins.’

4

I was still looking for Stroessner.

Juancito Chaves hadn’t helped, even with his memories; in their way, both Rubin and Zuccolillo had, but they didn’t know Stroessner’s whereabouts. I had searched through the official histories for clues to the man behind the deadly prose. I had walked around his city, trying to imagine how it was when his presence filled it. Nobody would admit to being in touch with him. Those who wanted me to talk to him couldn’t help. Those who might have helped didn’t want to.

But I was beginning to understand why he fell. After the easy money that followed the Treaty of Itaipu, his own system had begun to rot. By the time the dollars stopped flowing in, his two pillars, the army and the party, were crumbling. But there was also something else. There was social protest.

There were peasants demanding land, citizens demanding human rights and the Church, steadily, quietly, preaching solidarity and justice. In the land of no-science and no-truth, there were now groups burrowing away in the structure of the big lie, collecting information, writing newsletters, worrying the system. The Data Bank was one of them.

The Data Bank’s members always knew that information was subversive, but they never knew what information exactly would bring the police down on them. When Stroessner’s police finally raided, they didn’t just take away the people; they stripped the place bare. Typewriters, photocopiers, even the electric wiring out of the walls – all of it went (and when they raided a home, they took everything down to the last pair of socks). Even afterwards, no one could be sure what it was that they had done, this time. José Carlos Rodriguez, a sociologist at the Data Bank, one day found himself on the run with an order out to shoot him on sight. He escaped by hiding in the belly of the beast, taking a military flight to the Brazilian border, then hitching a ride with a police chief. ‘Nobody checks the papers of anybody who’s with a police chief,’ he said. Back home, the police followed his child for six months, waiting for the father to make contact.

Rodriguez at least knew he was guilty, even if he wasn’t sure of what. But there were many who were genuinely innocent: when the Data Bank was raided, a passer-by, who had gone inside to use the lavatory, was arrested with all the others. Who could know when he would be released? A famous case is Nelson Ortigoza’s. What he did, if anything, is now so lost in myth and counter-myth that it has ceased to be the point of the story. Nelson Ortigoza was in solitary confinement for twenty-five years. For the last two, his cell was bricked up. He was eventually released into house arrest, but escaped, helped in fact by my two friends Felino and Rafael. They say that when Stroessner heard the news he had a coughing fit that lasted four hours.

The resistance was growing, nevertheless, and, as more and more people were prepared to protest, more lawyers were emerging prepared to defend them. One of them was Pablo Vargas. Vargas had been in prison sixteen times, beginning in 1956 when he was thirteen. He was tortured four times, the first time when he was sixteen. In one session in 1969 he lost a kidney.

Vargas worked for the Church Committee, an interdenominational body that had been set up in response to a particularly brutal repression of a peasant organization in 1976.

I asked him if his work had been dangerous, and he gave me a weary look. We were sitting in a cool, whitewashed room, shafts of sunlight filtering through the shutters. I waited for him to answer, half-listening to the murmur of the street below. My question, I realized, must have sounded banal.

‘I saw many people die under torture,’ he said finally. ‘People used to ask me why didn’t I write about it, but I never wanted to because torture is something that nobody can describe. At one time I went to see all the films in which there was torture to see if it could be portrayed, but I found it was romanticized, idealized. What I saw on the screen seemed to me like a game for children.’

A person who is tortured, he said, becomes an animal. ‘It’s the most miserable thing there is. They tell you, “Rest. We will come for you at three o’clock.” And you watch the time pass. If they don’t come you pray that they have forgotten or that they have gone for somebody else.’

Inside those jails, the routine of torture had its own ritual, one that the prisoners got used to. When they heard loud music, they knew that, for somebody, the dance had begun. ‘I remember the pileta,’ he said. The pileta is popular in Latin America. It is simple, cheap and effective. It consists of holding a prisoner’s head down in bath water until he is nearly drowned. Then you haul him out. Then you put him back. Sometimes the water is clean, sometimes it’s sewage. ‘It was just a metal bath,’ said Vargas. ‘It had feet like lion’s claws. How often did I lie on the ground, looking at those feet?’

He was hunched over in his chair, looking at his hands. He stopped suddenly and looked round. The room was silent.

‘Why am I talking about this? I have never talked about this.’ He shrugged, his chair creaked. ‘When they begin,’ he continued, ‘you are naked. Your hands and feet are tied. The bath had one tap, and I would lie there, listening to that tap running, to the sound of the water changing as the bath filled, trying to guess how deep it was.’

He looked up. ‘The picana [electric prod] and the pileta don’t hurt, you know. People think they do, that the torture is pain. It’s not pain. It’s worse than pain. It’s like a small death each time: you long for pain in the end. It’s better to feel pain than that absolute despair. When they use the picana, you think you are going to explode.’

‘You talk to your torturer,’ he continued, ‘about anything. About fishing or food, trying to postpone the moment. The torturers tell you that they don’t like doing it and ask you to help stop it, to tell them something. But there’s nothing you can tell them. I have seen people tortured for twenty-nine days on end.

‘I could guess from the way they walked which one was coming for me. They were all different. Normally an interrogator would torture a man for half an hour at a time; then there would be another one, and then it would be back to the first. Sometimes they would torture two at a time, all the while comparing observations. And sometimes there were sessions that lasted four to five hours at a time, and during them they would talk about your performance. They killed a man once within the first half-hour, and they were very contemptuous of him. They’d had a girl of eighteen who had survived hours of it. “What kind of a man would die after half an hour?” they said. A good torturer doesn’t kill. You knew, if they broke somebody’s bones, it was because they were going to kill him.’

Torture had left him with bad dreams, he said, but he wasn’t unusual. ‘In Paraguay, fear was like a second skin, something we all wore on top of our normal skin.’

Today, Vargas is a senator. He is forty-six. Of the seventeen people who were in the leadership of his party when he was twenty-two, five are still alive. ‘You feel like an old man, at forty-six,’ he said. ‘Stroessner stole thirty-five years of my life. Thirty-five years of systematic human rights violations while the rest of the world was completely silent. One of my friends was arrested at nineteen and got out at forty. There were people who were in jail for twenty-two years without trial. There were cases of mistaken identity in which the accused were released after six months, but there were others in which they were forgotten for ten years.’

Like the man in the lavatory of the Data Bank, I thought, wondering how long it would be before he was set free.

I walked back towards the centre of town, to get some air, and found myself in the square, looking at the neoclassical Congress building. In front of it was a little Bolivian tank, a trophy from the Chaco War, painted the same municipal green as the benches and the little bronze statues that had been imported from France. The heat was suffocating except for a light breeze.

I sat on an empty bench and looked at the statue of Mariscal Francisco Solano Lopez, president of Paraguay from 1865 until his death in the disastrous War of the Triple Alliance in 1870. Lopez had nearly wrecked Paraguay, having been lured into a war against Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay; and, by the end, half of Paraguay’s population was dead. The last battles were fought by children from the cadet school, with painted-on moustaches.

Someone told me that his rearing horse had started out on ground level – it now rests on an oversized plinth – but the children used to daub him with paint. I liked the idea of the children’s revenge.

Behind me was the police headquarters. It takes up an entire block. The torture chambers were 300 yards from where I was sitting. Could the street noises be heard in the cells? What would it be like, to listen to the footsteps, people coming and going, indifferent? Almost everybody I met seemed to have been in jail. It was almost a commonplace, but few paraded their suffering.

Sometimes there would be a look: it was like the look you imagine crossing a soldier’s face when a kid asks, ‘What’s war like?’ Sometimes you could tell that there were questions that were being thought but not asked: Where were you when it was happening? Were yours among the indifferent pairs of feet I listened to from my cell? Why do you come now, wanting to know, when it’s all over? Where were you with your questions when my son was kidnapped outside my front door, when my brother was exiled, when I was in the pileta?

I went to have a coffee with Felino.

‘You want to know where they tortured people?’ he asked. ‘Everywhere.’

I wanted a list.

We went out on to the balcony and looked down on the city. It was late afternoon, and the roofs were bathed in a rich, golden light. Felino began to point out the buildings which had cells and torture chambers. After five, I stopped taking notes.

Rafael had been in most of them, said Felino. The windows of Rafael’s office, next door, had much the same view. I wondered: what did he think when he looked out?

‘Jail wasn’t so bad,’ said Rafael. ‘All the nicest people were there. One time I met a kid whose only crime was that he was a brilliant basketball player. His team was coming up against a general’s team, so the general had him arrested.’

I was getting depressed, wondering what I was going to say about Stroessner’s Paraguay that didn’t make it sound like a bad novel with an exotic backdrop: the comic opera dictator with the oversized hat, covered in gold braid. And where was the man, at the heart of it all? Nobody could tell me. They all had their own, oversized image. I was beginning to hear the same stories.

What made him laugh? I asked.

People stared back.

I phoned home, upbraiding them for the pain of my own absence, for the frustration of the story. My daughter had had an accident, in the playground, a cut over her eye. She was fine, I was told. I put the phone down and began to cry with the shame of not being there.

I turned over my notes, wondering if I had enough to stop.

I could see how it had all begun to fall apart, around the ageing dictator. He grew tired and no longer put in the hours. He began to ramble on old themes, to go off and play cards and chess with his cronies, to visit his mistress. His health began to give him trouble, and he didn’t like it.

What I didn’t know was how he felt about it. Whether he knew that he was losing his grip. What did he think about when he took off the gold braid and climbed into bed? Did he worry about his paunch? Did he notice his legs were growing thin? Did the decay of his body disturb him as he took those young women to bed?

I felt I hadn’t made sense of the women and it annoyed me. I wanted to know what it was like to be debauched by Stroessner. Did his subjects admire him for his appetite for teenage girls or detest him for his insistence on his rights as the national stud?

And why so many? Had he mixed up his appetite with his sense of national destiny? It wasn’t an entirely idle question. There had never been enough settlers in Paraguay. There had been too many wars, too many exiles. Everybody had a story of a grandmother, an aunt or even a mother abducted when a schoolgirl by a predatory male.

Stroessner’s neglected wife, Dona Eligia, was more pitied than resented. Behind the official first family pomp, people said, was a campesina who chewed tobacco, a concubine from his days as a junior officer whom he kept on as a wife, a prisoner of his insistence on the myth of official respectability. She could be got into evening dress for state occasions, but mostly she kept in the background, bringing up their three children, Gustavo, Freddie and Graciella in the official residence on Avenida Mariscal Lopez. Stroessner had separate quarters at the back.

Stroessner did not build lavish mansions on every corner. The public myth is of a man who lived ascetically, though, as someone pointed out, why bother, when the whole country is yours? But his way of affirming the reality of his possession, his absolute right, was through the women. The younger, it seemed, the better. His annual pilgrimage round the high schools presenting diplomas was mentioned in The Golden Book. The President, it said, took a keen interest in education. From the school platforms he would inspect the rows of schoolgirls and, when he spotted one he liked, she would be delivered to him.

In the early years, a Colonel Perreira acted as procurer for Stroessner. There was little point in resisting, and, in any event, the girls and their families were well rewarded. ‘You had hit the jackpot if your daughter came to the notice of a capo,’ said Rafael, ‘and if it was Stroessner, well, your dreams were made of gold.’ Nobody knows exactly how many girls there were, or how many children he had by them. When he tired of the girls, Stroessner had them married off to army officers who swallowed their pride and acknowledged his children as their own. But one or two lasted long enough to become public figures in their own right. I had tried to find some of these women. I talked to one on the phone, but she wouldn’t meet me. I talked to people who knew them, slightly, but it was gossip, funny stories of other boyfriends hiding on the roof when the General called unexpectedly. Nobody seemed to know or care what they really felt.

Then I met a woman who did, a friend of Maria Estela Legal, known as Nata, Stroessner’s most famous mistress. ‘I’ll tell you about her,’ she said. ‘But don’t use my name. I was just her friend, nothing political. Just her friend.’

Nata’s story, she told me, was a very Paraguayan one. She was the natural child of parents who each married somebody else. Stroessner picked her out of a school procession, when Nata was fifteen, and her mother gladly sold her.

Since she was too young to be given a house of her own, Nata was sent to live with one of Stroessner’s generals and his wife. The girl spent the first few months weeping with misery, but gradually resigned herself to her situation. In any event, there was no choice.

Stroessner talked to her regularly, took her on fishing trips. ‘He probably showed her the first real kindness she had known,’ said her friend. Nata became pregnant, and after her first daughter was born she was given her own house, where Stroessner would visit, every afternoon. She had a second daughter two years later.

Nata could have anything she wanted – cars, money, jobs for the relations who came flocking round. Her friend insists she didn’t abuse her power. She was nearly arrested once, by a zealous and ill-informed policeman who pointed out that the car, a present from the president, had no number plates. She didn’t make a fuss, said her friend, and would have gone to the police station, but a streetwise kid selling chewing gum alerted the policeman to the fact that he was on the brink of an important career error.

But it was a lonely life. In official circles, the done thing was to support the myth of the first family. At Nata’s parties it was always the same crowd, a couple of generals, a senator, her doctor, a plastic surgeon and two or three friends. Nevertheless Stroessner was devoted to both her and the daughters.

He went shopping at the supermarket himself and then went round to cook them meals. He helped the girls with their homework and was always there for birthday parties, answering the door himself. ‘He loved them, in his way,’ said her friend, ‘but I couldn’t have stood it. He was so authoritarian. They were never allowed to wear trousers because he said it was unfeminine. And he was fantastically jealous. Whenever Nata went out, he had her followed. I have seen him following her himself, all alone in a black car.’

Nata, as she grew older, tried to escape several times. Once, after a row about one of Stroessner’s many other amours, she left. She went to Switzerland and married an Italian antique dealer. Stroessner was desperate. He did everything to get her back. He hung on to the daughters, then aged eleven and thirteen. Nata was away for six months and then returned to visit her children, intending to stay for two weeks. She stayed three months. The Italian husband became jealous.

It was an impossible situation and eventually she came back. She had been married about four years. ‘It was so sad,’ said her friend. ‘She had been such a different person in Switzerland. She was able to go out, have a coffee, talk and laugh, just like anyone else.’

She was back but she was still lonely. Eventually she persuaded Stroessner that she needed to marry. A husband was found, an architect. The wedding was held in a house she had shared with Stroessner by the lake in San Bernardino, fifty kilometres from Asunción. The guests, on entering, walked under a large portrait of the president hanging in the entrance. None of Stroessner’s friends went.

After the marriage, it was business as usual, except for the husband, whose presence clearly irritated the General. Stroessner continued visiting the house that he had built for Nata on the airport road, always after the regular Thursday meetings of the army chiefs that he chaired as commander-in-chief, but on several other days too. At first the husband waited on the veranda but finally he was told to remove himself further and he took to playing bingo in a hall near the house. As it happened, the bingo hall belonged to Gustavo Stroessner. Stroessner was visiting Nata when the coup started.

5

People had begun to feel that change was coming. Dr Casabianca felt it. He had returned to Paraguay in 1983 after the newly elected President Alfonsin in Argentina had interceded on behalf of the exiled members of the Popular Colorado Movement. (Stroessner said that of course there was no problem, the members of the Movement had always been free to return, and that they should have asked sooner.) Dr Casabianca returned the next week and then spent the next five years being followed, harassed and arrested. When he was in prison in December 1988 – one of the last political prisoners of the Stronato – he said he felt then there was a change coming. ‘The police were polite to me. It was as though they knew it couldn’t last.’

The issue, finally, was the succession.

In most ways, Andres Rodriguez was the natural successor to Stroessner. For years he had been part of the corrupt inner circle. He had grown rich in the drugs traffic and had invested in land, breweries and a currency-exchange empire. By the 1980s he had shown signs of becoming nearly as respectable a businessman as Paraguay permits. He was commander of the cavalry, a key army corps, and he had a dynastic connection through the marriage of his daughter to Stroessner’s son, Freddie. For all these reasons, he was seen by the militants as the principal threat to Gustavo’s succession.

Gustavo had acquired a reputation for brutishness and greed, which might not have done him any harm, but also for homosexuality, which certainly did. If the father lived austerely, the children squandered lavishly. Local journalists estimate Gustavo’s winnings – culled from gambling, the drug trade and a string of ‘business’ interests – at 100 million dollars. His rise in the armed forces was viewed with resentment, and it ate away the foundations of Stroessner’s second pillar of power.

The militants – new money and friends of Gustavo – had won control of the party at the disastrous and violent convention in 1987. Juancito the Liar and his friends were ignominiously thrown out, and Sabino Montanaro was elected the new party president. He was also minister of the interior, had part of the stolen car concession, sold passports and dabbled in narcotics. He had been excommunicated at one point, for torturing priests.

The plan, people now say, was to call another constitutional convention and make Gustavo vice-president, ready to shove him upwards when the vacancy appeared. Gustavo’s friends and several die-hard militants deny this; some thoughtful bystanders wonder if Gustavo wasn’t so unpromising that even the militants had their doubts. Whatever the plan, it was true that this was the last, truly decadent stage of the Stronato, a combination of grand larceny and radical violence in the face of decay and no control.

The displaced Colorados plotted their revenge and the times were with them. Things were moving on the streets, strikes and demonstrations, backed by a Church led by the wise and courageous Archbishop Abimael Rolon. In January 1989, Gustavo was promoted to colonel and 150 officers above him were retired. Many of them were Rodriguez’s cronies, and Rodriguez began to smell a rat. The junior officers, for their own reasons, were bordering on a revolt. Rodriguez realized he was about to be caught between his junior officers – he would be engulfed in their revolt – and the new militant faction. And then Rodriguez was warned – people say that it was Pappalardo – that Stroessner planned to retire him. That was why, the story goes, Rodriguez pretended to have broken his leg and did not attend the usual Thursday general staff meeting, the week of the coup.

They moved the next day.

Ammunition and radios for the coup had been supplied by some wealthy industrialists, as, even in his decline, Stroessner was too canny to hand out too many bullets to his own army. In the afternoon, Nata’s house was attacked: Stroessner was there having his customary siesta. His bodyguard gave the old man enough cover to allow him to escape, and he went off with his own élite unit, the presidential guard, although even here, few fought with any conviction. His generals had so long neglected military affairs that they could scarcely remember how to give orders, and the tanks in the élite unit couldn’t move because the man with the keys was out of town. Only around the police headquarters was there serious fighting. By the next morning, Stroessner and his family were packed off on a flight to Brazil, and there was dancing in the streets.

Felino told me how he went out looking for a statue to topple. ‘They were surprisingly hard to find. After thirty-five years we finally noticed he didn’t put up statues.’

Felino found one in the end and knocked it over.