A friend of mine met Freddy during the summer. The meeting lasted less than half an hour but it affected her deeply. She told me about swimming with a dolphin in the sea off the north coast of England. The dolphin’s name was Freddy. She gave me the number of the lifeboat mechanic who took her in his boat to meet the dolphin. I thought of telephoning the man to arrange a meeting, but for some reason I didn’t get around to it.

Some months later I was reading a newspaper when I noticed an article about an animal rights activist prosecuted for an act of indecency with a dolphin. The man was accused of ‘committing a lewd, obscene and disgusting act and outraging public decency by behaving in an indecent manner with a bottle-nosed dolphin to the great disgust and annoyance of divers of Her Majesty’s subjects within whose purview the act was committed.’ The dolphin was called Freddy. I tried telephoning the man with the boat but there was no reply. The trial ended in an acquittal. The dolphin was still at large. I decided to go to Amble.

I started north one morning before sunrise with a friend called Simon. We arrived in Amble at midday and parked the car by the community centre. The walls were scrawled with graffiti: Angela is a dog. Fuck. Biff and Munch. Paul is a Lush. On the way to the waterfront we passed Johnny’s Bingo and Social Club. The sign in front read, ‘Open 6.30-10.00 p.m. daily, keep clear.’

We were the only people on the waterfront. Seagulls cried over the sound of mast lines tapping in the wind. We were cold and hungry and went into the first pub we could find. The room had a low ceiling. A group of men stood at one end of the bar and a big man worked the beer pumps.

We ordered beers and the man offered us a choice of sandwiches: cheese and tomato, cheese and onion, or corned beef – ‘Beef in a tin,’ the big man said. ‘Corned beef. You’ll enjoy it.’ He tore two squares from a roll of paper towel, put them in front of us, and placed our sandwiches – one cheese and onion and one corned beef – on the squares. He made little grunts as he moved. He smiled and asked if we’d come to see the dolphin. ‘It’s the fifth largest tourist attraction in this part of England,’ he said. ‘I forget the others. But it’s the fifth.’

Dunstan had Dunstanborough Castle; Howick had Howick Gardens; Amble had the Dolphin.

‘With the mines closing and the fishing industry dying it’s not easy. Twenty per cent unemployed, maybe more. Nobody knows with all the retraining schemes these days. But the dolphin makes a difference. Apart from the pie factory the only work is painting and decorating, or the tourist trade. The dolphin’s been a big tourist attraction.’ We ordered more sandwiches and asked where we could stay for the night. The big man said there were rooms in a guest-house near the harbour. The people there knew the operator of the boat which would take us to the dolphin.

As we put on our coats he wished us a good time with the dolphin and someone called out to us, ‘Don’t do anything I wouldn’t do,’ and they all laughed and one said, ‘You’d do anything.’

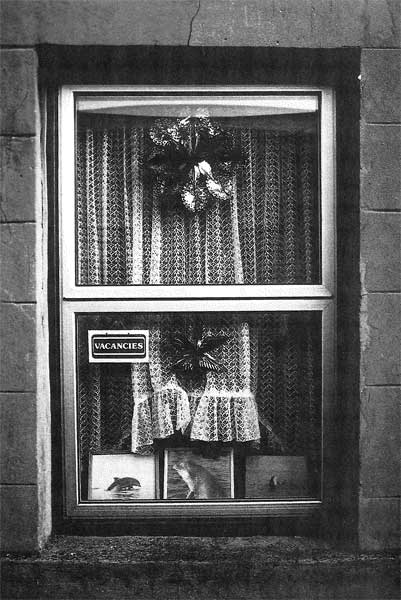

The windows had net curtains and there was a sign saying vacancies over three photographs of dolphins. Mrs Henderson greeted us. She was a large middle-aged woman wearing a T-shirt with the words, ‘Freddy, the friendliest dolphin’. The rate was eleven pounds a person for bed and breakfast. She had a kind face but seemed nervous. She asked if we were vegetarians. We said we were happy with anything.

‘Some of them aren’t,’ she said, her face relaxing. ‘I put a plate of bacon and eggs in front of one of them and he went Aaargh! I told him I’m not a mind-reader. But that’s what some of them do when they see it. Aaargh! Not just meat. I’ve even had some of them do it with kippers. That’s why I always ask them, just in case. Make yourselves at home anyway.’

The television room was at the end of the hall. The bedroom was up the stairs and to the left and was unlocked. If we wanted anything we had to knock on a glass door marked PRIVATE. Mrs Henderson said there would be a pot of tea for us in the television room when we came back from the dolphin.

The bedroom had two beds, a wash basin, a chair and a cupboard. There was a picture of a rose on one wall. The window looked over the car park and the harbour, up the river to the castle in the distance.

At the harbour we waited to meet Gordon Easton, who operated the boat. I read an information sheet distributed by International Dolphin Watch on the Amble Dolphin.

On 25 September, Freddy the dolphin, who has stayed in the mouth of the river Coquet at Amble for the past three years, was struck by a propeller and suffered eleven lacerations on his right flank … In order to give the cuts the best opportunity to seal and obviate opening of the wounds by accidental contact with fins etc. it was requested that swimmers should stay clear of the dolphin, and notices to this effect were posted in Amble . . . On a visit to Amble on 7 and 8 October I was able personally to observe Freddy and swim with him. From these interactions I gained the distinct impression that Freddy was missing the level of contact he normally enjoyed and was deliberately seeking human company. Indeed, while I watched him from a boat, Freddy swam away, caught a fish, tossed it in the air and played with it vigorously before consuming it and returning to me.

I looked at the bottom of the page. It was signed: ‘Doctor Horace E. Dobbs’. I read on.

Gordon Easton, the mechanic of the lifeboat, has spent more hours at close quarters with Freddy than anyone else. He has agreed to act as our Dolphin Ambassador in Amble. As such he is happy to take visitors out in his boat and advise them how to behave in the water in the presence of the dolphin.

I wondered what Gordon Easton, lifeboat mechanic, on call night and day to rescue people from the waters of the North Sea, thought about being appointed Dolphin Ambassador, and what he thought of Doctor Horace E. Dobbs.

A man with tousled reddish-blond hair came towards us along the jetty. We introduced ourselves and Gordon Easton said we’d come at the right time: the tide was out and the sea calm. I was asking if the dolphin was about, when I saw, over Gordon’s shoulder, beyond the pier, a movement like a wave, only different, on the surface of the sea. ‘That’s him,’ said Gordon. ‘That’s where he likes to be.’

I got into the boat and put on a dry suit over my jeans and sweater. Gordon’s dog chewed at the arms while I tried to find the legs. I pushed my head up through the neck and Simon zipped me across the chest. Gordon turned down the motor.

‘Wave your arm if you’re in trouble,’ he said. ‘You don’t want water leaking in. The cold creeps over you. Don’t leave it too late.’

I pressed some air out through the valve over my chest and put a leg over the side of the boat. Simon told me to look happy and I lowered myself into the water.

I floated without any effort. The spray from the waves blew in my face and my hands were freezing. The rest of my body was warm.

Gordon’s dog became excited. He looked over the side of the boat, wagging his tail and barking. Gordon had said that the dog would know when the dolphin was near. I was wondering if I would have an intuition or feel an underwater vibration passing through my body, when there was a gush and a hiss behind me and a smell of fish and a splash. I knew the smell – fish eaters’ breath. The hairs on the back of my neck were rising, and I felt like a clumsy star of arms and legs above the dolphin.

A touch on my right hand, then a few seconds later, on my left. He knew exactly where his body was in the water – he was under the surface moving past my right hand again, just touching, caressing. He did the same with my left. It was like a greeting; it had pattern and symmetry.

I was some distance from the boat. The dry suit supported me. The dolphin had vanished. Perhaps he’d checked me out with his sonar, and the meeting was over. I swam towards the boat. Then I felt something tapping the soles of my feet and saw air bubbles rising in a plume and breaking the surface around me.

I got closer to the boat. Gordon asked if I was OK and I said yes. I imagined the dolphin chasing fishes under my feet. Suddenly he broke the surface just beside me in a glistening arc of silver-grey flesh set with a great eye, and as he rolled over I rested my hand on his body and felt where the propeller had cut him: a dozen or so straight ridges of scar tissue at regular, machine-made intervals.

My hands were freezing; an icy sensation worked down my back and around my waist. I worried about a leak in the suit. The dolphin reappeared, this time almost head on, and I stroked him like Gordon told me, under the neck which was soft as a silk stocking underwater, and as he dived I felt the end of his fin at the tips of my fingers.

It wasn’t easy getting into the boat. Simon helped me on to the deck. The sleeve of the dry suit had trapped part of my sweater. I pulled back the rubber cuff and water poured out as if I’d turned on a tap. Gordon laughed and asked if I was warm enough.

On the way back Gordon told me about the people who came to swim with the dolphin. ‘You get all types. Mystical ones,’ he grinned. ‘They come from all over the world – Germans, Swedes, Hawaiians. Some of them are surprised by how we live. We’re poor. There’s a lot of poverty.’ The way he said the word ‘poverty’, as a farmer might speak about a drought, or a fisherman describe a season of empty nets, made it sound like a natural misfortune. I thought of the shops selling bric-à-brac in the high street, with names like Nostalgia and Memories.

I asked about the dolphin’s scars. Gordon explained how the accident happened. A member of the Royal family was visiting the lifeboat station. A lady-in-waiting wanted to see Freddy and a police launch was commandeered. Freddy was used to boats with single propellers. The twin propellers of the police launch confused him. He misjudged a turn and a propeller caught him along his right flank. The cuts were six inches deep. ‘It was a miracle he wasn’t killed. But he just carried on as normal. He still likes coming up behind boats and getting close to the propellers.’

Back at the guest house I stripped off my wet clothes and had a hot bath. Then I joined Simon in the television room. He was reading the visitors’ book.

A gas fire was burning. On the television was a collecting box for the Royal National Lifeboat Institution. The receipts for the past eighteen months were carefully displayed. Over the fire and by the door were pictures of lifeboats; two framed photographs of a helicopter rescue hung above the television. The other pictures were of dolphins: looming out of a watery darkness like a white shadow, silhouetted against the sun-freckled surface of the sea, a smiling prodigy.

There was a knock at the door and Mrs Henderson appeared. She didn’t come right into the room but stayed by the door.

‘Did you get the touch?’ she said.

I described what happened.

‘You were lucky,’ she said. ‘He’s got you first time ever. Not everyone gets the touch.’ I asked if she had had it. She closed the door and sat on an arm of the sofa.

‘I shouldn’t have been in the sea. It was really choppy. I didn’t think I was going to get it. My first touch – I was standing on him. Marvellous! I thought, I’m on solid ground. He was underneath my feet. But my husband’s never seen Freddy. He doesn’t like water. He almost drowned when he was a child. You won’t get him into a boat.’

Simon asked how the dolphin came to Amble, and she told of the first sighting by the men at the lighthouse, three years before. At first they thought it was a shark. Then someone from the Dolphinarium at Flamingoland confirmed it was a dolphin. ‘Gradually he got closer to people. They thought he’d come here to die, he was so thin. But now he’s big and strong. He’s found a good feeding spot at the mouth of the river – the salmon sense fresh water and they swim towards it. Freddy waits for them between the pier and the headland. A few fishermen complain, but we’re all fond of him. No locals have gone overboard – if you know what I mean, no nutters. It’s not like the dolphin at Dingle in Ireland. There’s no racket here.’

Simon asked who the ‘nutters’ were.

‘I’d prefer not to talk about it,’ she said. ‘The court case and everything. There’s a lot of feelings, if you know what I mean.’ There was an awkward silence. Simon said how much he’d enjoyed reading the visitors’ book. Mrs Henderson smiled.

‘We’ve had some lovely people here,’ she said. ‘All sorts. Ones with emotional problems who come for healing. We had youngsters here who were involved in the Hillsborough disaster. Angie was one of identical twins – a car killed her sister, she was lost without her. But when she’d been swimming with Freddy she realized there were other things in life. Nicola was a kidney transplant girl – a little spelk of a girl. Freddy helped her.’

I asked Mrs Henderson how old Freddy was. She arranged a cushion on the sofa. ‘He won’t be here for ever. One day a mine will go off. The new-fangled nets go deep and sometimes they pick up mines. Someone caught one in his fishing net. The mine disposal lads came to stay here. I did some sarnies for them. I was afraid that Freddy would follow their boat. They wanted to keep Freddy behind the pier, but he went near the mine. I couldn’t watch. I was trying to tidy up in here with a friend. We heard it blow. She said, “I’ll go and see.” But he was fine. Fifteen of us sat in the kitchen celebrating with the lads. It was this time of year, before Christmas. I went down to Newcastle and I’ve never enjoyed shopping so much. Anyway,’ she stood up, ‘it’s time I was feeding the dog.’

When she had left I opened the visitors’ book and read.

Cliff and Gladys from Darlington: comfortable friendly stay. Exciting dolphin watch.

Kutira from the Kahlua Hawaiian Institute: an outstanding experience to swim belly to belly with Freddy–Kealoha (love) his new Hawaiian name. To undulate and feel the loving touch and wisdom of this beautiful friend. Also don’t miss Gordon the Keeper of the Dolphin-Wisdom. He is truly a guide into the Dreamtime.

Steve: gob-smacked!

Maria: back again. I need to visit Freddy and Amble. Shame about the wild sea, only got in once, but it was enough for my baby (to be). Twelve weeks into pregnancy to say ‘hello’ to Freddy. I will be back when I’ve had the baby to introduce them properly. Special thanks to all who make us feel so welcome. It’s home from home.

In the morning, after breakfast, Simon called his girlfriend and I changed into the dry suit in the television room. It was easier without Gordon’s dog chewing everything. We stepped outside and the air was cold. The snow in the shadows was the colour of the sky; the snow in the sunshine was whiter than the back of a Christmas card.

Gordon was waiting for us. We climbed into the boat. There was ice on the ropes and snow on the deck. ‘Beautiful morning,’ Gordon said, ‘not too cold. When it’s very cold, the ropes are frozen solid. You have to piss on the ropes to untie them.’

The dolphin joined us at the mouth of the harbour.

‘He heard the boat’s engine,’ said Gordon. ‘He knew it meant visitors.’

Once again the dolphin presented his body to my hand, slid by my fingers and turned over with a lazy splash. The white flesh of his belly felt as smooth as melting ice. The scars passed under my fingers. For a moment his eye looked, or seemed to look, into my own. Then he rolled over and his tail was in the air and and he was gone.

‘That’s how he says goodbye,’ said Gordon. ‘He’s busy feeding now. He won’t come back till he’s finished.’

We shook hands and I said we hoped to come again. ‘Let’s hope Freddy’s here as well,’ said Gordon. Then we loaded our things into the car, said goodbye to Mrs Henderson and drove south.

Photograph © Simon Wescott