July 2020

I finished this essay in early January, a few weeks before Covid-19 was appearing regularly in the news. I was superficially familiar with the family of viruses having spent the previous three years attempting a crash-course in epidemiology as part of a research project. Slowly working my way through ‘disease literature’, Giovanni Boccaccio’s The Decameron (1351) had seemed a timely end-of-decade read for the reasons I lay out in the essay below.

Reading back under lockdown conditions, I have new questions about the fragrant garden frequented by the brigata – The Decameron’s young, wealthy Florentine narrators – and the privileged means by which they were able to escape the contagion of the city. Boccaccio’s description of wild animals’ newfound boldness in the wake of the plague, freed from the threat of hunters, recalls the widely-shared images and videos of wildlife ‘unleashed’ during our current pandemic: goats and deer cruising deserted city streets, fish in the glass-clear canals of Venice.

Among the many news articles I have found harrowing in recent months are those predicting – and later confirming – the rise in domestic abuse cases under lockdown. For many women, the conditions that both catalyse and enable their partners’ violence and coercion have been dangerously amplified. Speaking to The Independent in October 2019, the domestic violence charity Refuge reported that around a third of the women they support have also experienced financial abuse at the hands of current or former partners. And for those who have escaped financially abusive partners prior to lockdown, the pandemic’s heralded economic downturn has, in addition, exacerbated consequent anxieties regarding security and wellbeing. In such times, the misogyny built into the architecture of social life in The Decameron does not seem so far away. Perhaps that is why I still find myself circling back to the wild retreat of the Doe, and Fortuna – the ‘fickle’ goddess of flux and change.

In the last month of the decade I find myself reading Boccaccio’s The Decameron for sanity. Almost everyone I know is in a state of profound political grief, my friends and I are sick with the realisation that the entirety of our twenties will have been spent under a Tory government. I am four months on from leaving a relationship, and trying to navigate the resulting financial abuse which detonates my inbox on a weekly basis.

In between teaching poetry to undergraduates, tearful conversations with friends, talking to lawyers and worrying about rent, I sit down with The Decameron. Writing in the still-smoking aftermath of the Black Death, Boccaccio witnessed first-hand the effects of the disease which culled the population of his native Florence by half. By 1349 the epidemic was in decline, Boccaccio was thirty-six and had just lost his father. He started work on The Decameron in media res, long before the dust had begun to settle.

The Decameron follows a ten-day jaunt taken by the brigata, a group of ten Florentine men and women aged between seventeen and twenty-seven, who decide to escape the city’s contagion by fleeing to an idyllic rural villa. Once installed in their new environs (miraculously replete with servants who prepare their meals and rooms) the brigata decide they will pass the time and entertain each other by telling stories. Each day one of them is crowned king or queen, whose privilege it is to choose the topic of the day’s tales. A variety of rituals accrue around the telling of these stories, which unfold in the villa’s fragrant gardens. Over the course of their stay, each day’s ten stories tally up to a dizzying total of one hundred tales, giving The Decameron its name.

For a book whose characters come together to escape a plague-ridden city, there is surprisingly little to no mention of disease; it’s as if – through the vertiginous volume of stories they share – the characters are lulled into forgetting the circumstances that brought them together. In his introduction, Boccaccio addresses the reader directly, imploring forgiveness for his use of the plague as narrative conceit; he explains that there were no other credible means by which he could get his characters out of the city and into a setting where these stories could unfold:

You are to look upon this grim opening as travellers on foot confront a steep, rugged mountain: beyond it lies a most enchanting plain which they appreciate all the more for having toiled up and down the mountain first.

The plague is a narrative wrecking ball, a colossal trauma that cracks open the book’s characters to remake them as conduits for tales of fate and fortune, threat and injustice, supreme happiness and abyssal despair. The lives played out in the hundred stories of The Decameron are buffeted by the gales of Fortuna, Roman goddess of fate, luck and fortune. Some live good lives and are variously rewarded or punished, others cheat and lie, some kill for vengeance or for love, others are killed and come back from the dead. Some lose everything, while others gain the world. The characters that make up this brigata inoculate themselves with these narratives like homeopathic doses against the loss of life and social order brought about by the plague.

In the days and weeks I spend with these stories, I find The Decameron no less homeopathic (or hair of the dog, a phrase deriving from a fabled cure for rabies) in its ability to allay or distract than it was seven hundred years ago. Between its characters I locate fourteenth-century accounts of gaslighting and coercion passed off as run-of-the-mill business as usual. The stories are unsurprisingly laden with misogyny – as well as unusual depictions of female agency – but there is something about the mundane ubiquity of pettiness and aggression that fortifies me against the present. In reading on, I come to identify the source of this fortitude in the figure of Fortuna.

Postcard of Fountain of Fortune in Fano

Like many Roman deities Fortuna is a palimpsest. She subsumed her Greek equivalent Tyche, goddess of luck, fate and fortune, and gained allegorical currency in medieval literature following her appearance in Boethius’s The Consolation of Philosophy (524 CE), which personifies her through another personification, Lady Philosophy. In The Consolation, as elsewhere, Fortuna gets a bad press. Her association with flux and change (her name derives from Vortumna, she who revolves the year) often led to her being perceived as fickle, moody and truculent. Machiavelli deemed her two-faced, while Ovid described her as a goddess ‘who admits by her unsteady wheel her own fickleness’. ‘Unsteady wheel’ refers to the goddess’s rota fortunae or wheel of fortune that she is often depicted with, steered by a gubernaculum – a ship’s rudder – in one hand, and holding a cornucopia or horn of plenty in the other.

The unruly coupling of Fortuna’s ability to offer abundance, symbolised by her cornucopia, and the volatility of the gubernaculum, which can throw any traveller off course, are perhaps why Fortuna is so easily made into allegory’s ‘bad object’. There is nothing meritocratic about the chance winds of fate; devotees of Fortuna must submit to flux, contradicting virtuous narratives of earning one’s way into heaven. Unlike the majority of medieval depictions of Fortuna, Christine de Pizan grasped the radical and transformational powers of the goddess; in The Book of the Mutation of Fortune (1403) Christine is changed from woman to man at the hands of Fortuna. Writing from the vantage point of this metaphorical transformation, Christine is able to critique gender inequalities by laying out everything now available to her as a man that had been denied her as a woman. As Barbara Newman comments, Christine’s miraculous sex change postulates that ‘identity is shaped not only by birth, but just as much by random chance and political circumstance.’ Fortuna as pseudo-goddess is an existential force that cuts through the bonds of society, upending hierarchy, order and status quo.

In The Decameron, Fortuna – anglicised to ‘Fortune’ in my translation – is more abstract force than figure. Intangible and yet, like wind, discernible by dint of her effects: the vicissitudes wreaked on the mortal lives in each of the book’s hundred tales. Boccaccio wrote about Fortuna in later works, demonising – in the familiar vein of other medieval writers – her burning, threatening eyes and cruel and horrible face. While the misogynist overtone of medieval attitudes toward Fortuna reinforce a view of women as fundamentally capricious, changeable and deceptive, the gendering of Fortuna falls in line with the tradition of personifying virtues and vices as female. When the eighteenth-century essayist Joseph Addison first noticed this, he explained it as a side-effect of grammar, stating that abstract nouns in many romance languages (including Latin) take the feminine gender. Revolved by the fickle wheel of vernacular, abstract concepts accrue form and figure, leading to the feminisation of fate.

It’s no wonder that in a book written in the midst of an epidemic the figure of Fortuna is so predominant. Like the plague, Fortuna is capable of upending societal order, striking down the wealthy and indigent alike. The Decameron is not so much deflection from the epidemic as transference; by immersing themselves in the book’s cyclicality of narratives, its deluge of beginnings and endings, the constant turning of Fortuna’s wheel, the narrators might be immunised against the apparently random cruelness of the Black Death.

‘The random developments of Fortune are no easy thing to bear, indeed they are an affliction.’ So begins the sixth story of The Decameron’s second day, related by Emilia, the second youngest of the brigata. Whether the strokes of Fortune are lucky or not, Emilia says, we should never be reluctant to heed them, because we can learn from the lucky strokes and take comfort from the unlucky. She tells the story of a Neapolitan noblewoman, Beritola, who resided on Sicily with her husband, governor of the island. They lived happily until one of their enemies was crowned King of Sicily, whereafter her husband was arrested. Heavily pregnant and penniless, Beritola fled with her eight-year old son to a nearby island. There she gave birth to another son, whom she named ‘the Outcast’. All three boarded a boat with the intention of returning to Naples, but a strong wind carried them to another island, remote and uninhabited, where Beritola decided to wait for more favourable winds to take them home.

It was on this island that Beritola broke down. Each day she left her two sons to play by the seashore, and withdrew to a cave to grieve everything she had lost. She became so absorbed by her lamenting that one day she returned to find her sons missing: she saw a pirate galley on the horizon and realised they had visited the shore and taken her children as spoils. This second trauma is too much for Beritola to bear and she faints where she stands, succumbing to gravity and sleep.

In reading, I find myself resisting the interpretation that Beritola’s grief-state was responsible for the loss of her children. If she had held back tears and gritted her teeth making sand castles on the beach, the pirates would have taken her too – or worse. Her withdrawal was also her conflicted survival. When Beritola wakes up on the beach she retreats to her cave, where she sees a doe leaving the entrance and heading into the woods. Inside the cave Beritola finds two fawns, only just born. The sight of them thaws the edge of her grief; she gathers the fawns to her and begins to suckle them, her breasts still swollen with the Outcast’s milk.

Emilia tells us that the fawns suckle at Beritola’s breasts as they would their mother’s teats, and that from then on they make no distinction between their two mothers, animal and human. Beritola settles down to live with the fawns and the doe, with whom she develops a kinship. She ‘reverts to a state of nature’ and becomes ‘swarthy, lean and hairy’. Later in the story, Beritola returns to society with the two fawns and their mother in tow, and is thereafter referred to as ‘The Doe’. By various exploits of Fortune, The Doe is eventually reunited with her human family, who live happily (and wealthily) ever after. Emilia – or Boccaccio – neglects to mention what happens to the fawns and their mother.

The story compels me precisely because I wish it could end halfway through. The second part, concerning the strings Fortune pulls on to return The Doe to society, to reinstate her as Beritola the noblewoman, seems more like a misfortune. When her bonds with society are broken Beritola forges alternative languages of care, nurture and relation. Perhaps I can’t help but overinvest in these fantasies of retreat and insularity, for The Doe to stay on the island with her new family, for her human identity to gather moss. To resist the closure of return. But such fantasies cannot be left unchecked: does the island function as a mythic idyll, unspoiled by hierarchy, in which interspecies love might elapse without obstacle? In becoming The Doe, does Beritola leave the burden of human dominance behind her, or by loving the fawns does she also domesticate, contaminating them with her need?

Narrative has its own needs and ends. Tragedy exiles Beritola to the island, while the narrators of The Decameron live out a self-imposed exile beyond the city’s bounds. Beritola finds interspecies solace; the brigata console themselves with narrative. The cyclical nature of The Decameron’s stories bring about faux-closure that the plague has ridded them of.

Like the desert ascetic Mary of Egypt – traditionally depicted as a ‘wild woman’ whose long, unkempt hair hides her nakedness – Emilia spins a tale of female ferality that disrupts the social order and nuclear family. Through suckling the fawns Beritola also resembles Potnia Theron, the mistress of animals, a popular motif in ancient Mediterranean and Near Eastern cultures. Usually depicted as a female figure flanked by two animals, the connections between various cultures’ Potnia Theron imagery is unclear, making the mistress of animals not so much an individual as a clade of associations and affectations.

Potnia Theron with swan

In the midst of a zoonotic outbreak like the plague, Potnia Theron signifies both transmission and transgression. Her affectionate proximity to animals is also potential contagion and infection. Similarly, Beritola’s sharing of bodily fluids – her breast milk – parallels the plague’s interspecies transmission laid out by Boccaccio in his quasi-epidemiological introduction:

So potent was the contagion as it was passed on that it was transmitted not only between one person and the next: many a time it quite clearly went further than that, and if some animal other than a human touched an object belonging to a person who was sick or had died of the plague, the animal was not merely infected with it but fell dead in no time at all.

Though they rarely mention it in the course of their raconteuring, we know the characters listening to Emilia’s tale are familiar with the nature of this contagion. Boccaccio’s focus on infection across species boundaries pre-empts what we now know about the plague’s transmission; animals – most often rodents and small mammals – are bitten by infected fleas, and then act as vectors who spread the disease to other species. In the case of the Black Death, we know that rats carrying the plague bacillus – Yersinia pestis – arrived in Europe via an established trade route from the Black Sea, on ships carrying luxury goods. In October 1347, twelve ships docked in Messina, Sicily’s main port, and the disease quickly spread across the city and spilled into the countryside as people fled the outbreak. Beritola’s fictional flight from her hometown mirrors the plague’s transmission route through Europe, as the ships expelled from Messina carried the bacillus to neighbouring islands.

Denise Riley reminds us that ‘affection’ is an archaism for ‘disease’; the story of Beritola as The Doe blunts any sharp distinction between the two. The Doe is infected by her affection for the fawns, who might also infect her, and who, by receiving The Doe’s affections might also be infected by the disease of domestication. Never uncomplicated, affection between species is the cup of temperance whose waters run in both directions.

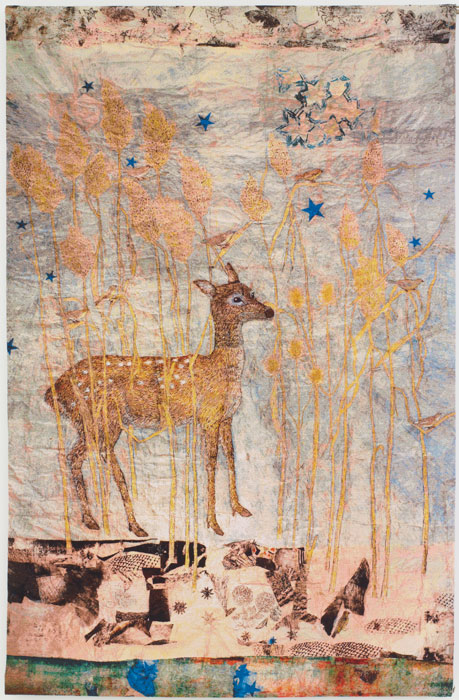

Fortune, 2014 © Kiki Smith, courtesy Pace Gallery, published Magnolia Editions

A few days after reading Beritola’s story for the first time, I meet Fortuna in Oxford. She’s taken the form of a doe and stands in a glade of ambergris threads, partially obscured by tall grasses and haloed by golden seedheads and stars. This doe, Fortune (2014), was woven on a jacquard loom by the artist Kiki Smith. Below the high white ether of the gallery space, Smith’s tapestries are the terra firma, each one a dense and intricate chaos of animals, elements, symbols and texture. Long before I discover its title, the composed but alert doe of Fortune is the creature I find myself lingering in front of.

What is the nature of correspondence, of coincidence? When I eventually locate the tapestry’s title I feel a familiar surge of excitement: the adrenal thrill of coincidence. There is no doubt in my mind that Smith’s doe, Fortune, is The Doe, Beritola, buffeted by Fortuna from the human to non-human world and back again. Standing in front of Smith’s tapestry I feel as though Fortuna’s musky scent and cloven hoofprints have led me here, so that I can see the brute serenity in the doe’s expression. A gift of fortitude. Correspondence as a kind of tracking.

In Alan of Lille’s mid-thirteenth-century text Anticlaudianus, the figure of Fortuna ‘weeps with one eye while the other eye twinkles’, no doubt intended as a slight on her capriciousness. But the goddess’s split expression might also be read as the hard-won vigilance and resignation of Melanie Klein’s depressive position, an outlook which accommodates the flux of good and bad. Fortuna is far from the splitting of the paranoid-schizoid position, one who cannot allow good and bad to mingle from the same source.

In Anticlaudianus, Fortuna’s daughter, Nobility, reveals the whereabouts of her mother’s abode, described as ‘Fortune’s isle’. Fortune’s Isle is perhaps a cognate of the Fortunate Islands, which figure in Greek mythology as the earthly equivalent of the Elysian Fields: a winterless paradise reserved for heroes. Pliny’s Natural History recounts that the Fortunate Islands ‘abound in fruit and birds of every kind’, and it is perhaps due to its clement weather and fecundity that these mythic isles have often been conflated with Sicily. Beritola’s story begins on Sicily, where she lives in wealth and security – Fortuna uproots all this and deposits her, alone, on a far-flung island. At what point in the narrative does Beritola encounter Fortune’s Isle? Is it the home she leaves or the one she finds?

As the site of both bereavement and healing, Beritola’s island is as ‘two-faced’ as the goddess herself. Beritola loses one family and gains another; she loses one identity and becomes The Doe. Similarly, the island figures as both mythic isle and lazaretto – a plague island or ghettoised port where infectious persons were detained. Beritola resides on her lazaretto, infected by interspecies love and its connotations of contagion and transgression. Later in The Decameron, Boccaccio’s introduction to the eighth day seems to act as a gloss on Beritola’s newfound family:

. . . as they entered [the little wood] they saw deer, roebucks, and other such animals who just stood and awaited their approach, for all the world as if they had quite lost their timidity or become domesticated – the ravages of the plague had given them a respite from the hunters.

In addition to upending society, the plague has also undone and recomposed species hierarchies, as if animals and humans might now live together in harmony. Compelling as this might be, Boccaccio makes it clear that such a state is undesirable, insofar as the narrative eventually retrieves Beritola from interspecies purgatory and restores her to society and the nuclear family. Like the brigata’s idyllic garden, Beritola’s island is both a refuge from civilisation, and its limbo. Perhaps in listening to story of The Doe the brigata hope for a similar denouement, that – if Fortuna’s wheel is willing – they might be able to return to life as it was before the epidemic.

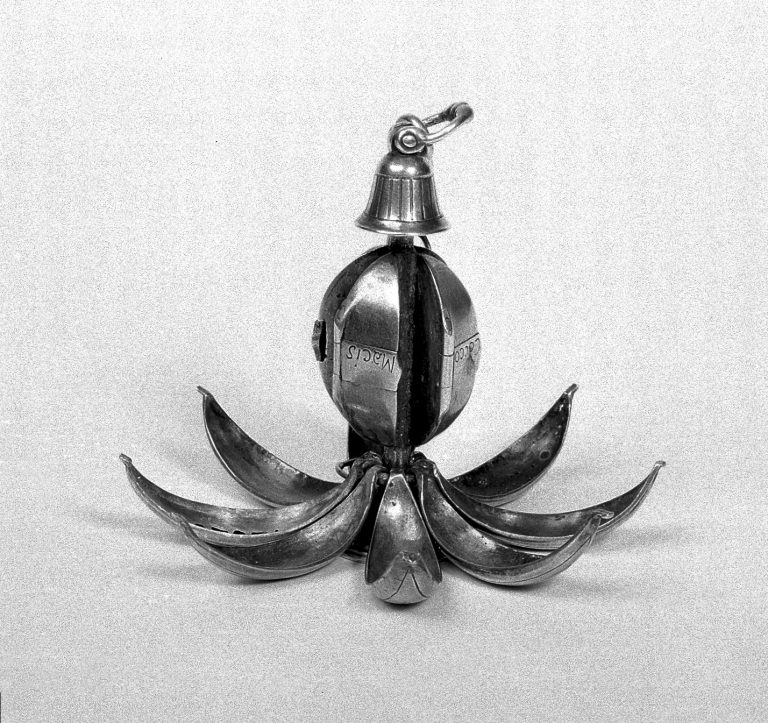

Pomander, silver. © Wellcome Collection

As well as adhering to the conventions of courtly love, the brigata’s garden retreat allegorically mirrors the behaviour of their fellow Florentines back in the city. In reaction to the piles of bodies piling up in the streets, Boccaccio’s introduction describes how certain citizens ‘would go about holding flowers to their noses or fragrant herbs, or spices of various kinds, in the belief that such aromas worked wonders for the brain (the seat of health), for the atmosphere was charged with the stench of corpses, it reeked of sickness and medication.’ The scented sensorium of the brigata’s garden, with ‘flowers in season everywhere’, recalls the fragrant balls filled with herbs and spices – pomanders – that many people carried in attempt to ward off the plague’s malodour.The Black Death rocked the medical establishment and spurred a concomitant outbreak of treatments, panaceas and nostrums. For every traditional doctor who despaired that the plague lacked precedent, that Galen and Hippocrates were no help to them now, several mountebanks would take his place plying alleged cure-alls. For the outbreaks of plague that followed, pomanders became a mainstay for their allegedly preventative faculties. Their form and ingredients varied along class divides, from elaborate globes of precious metal filled with rare and expensive substances, to oranges studded with cloves. Rosemary was consistently popular, so much in demand that it caused an enormous hike in price, and deer musk obtained from the caudal glands of male musk deer was often used to soak rose petals.

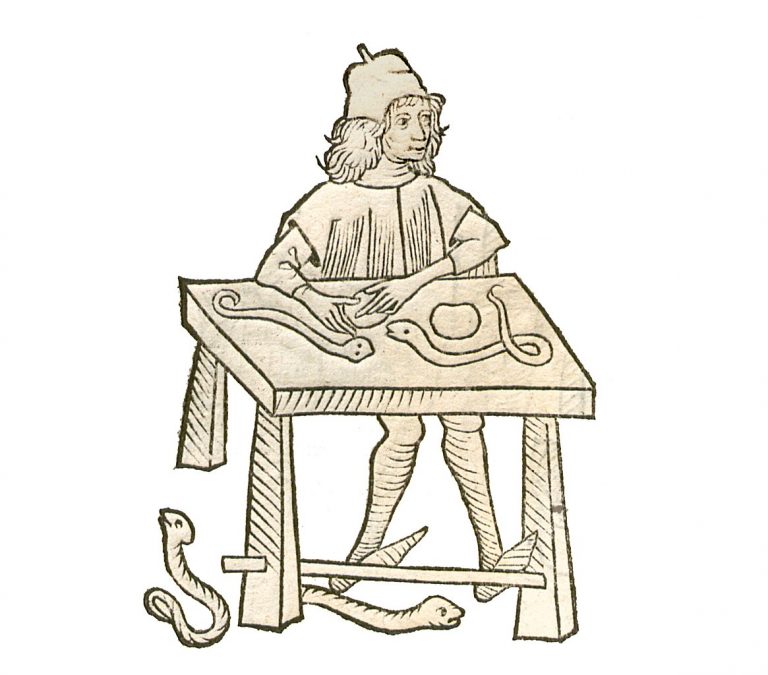

Perhaps the most consistent treatment was the ancient antidote theriac, since the plague was believed to act in the body like a poison. Theriac of Andromachus was one of the most complex medicines in the pharmacopeia, containing as many as eighty-one ingredients such as viper flesh and bezoar stones. Andromachus was a physician from Crete who attended the emperor Nero for over a decade, to whom he dedicated an elegiac poem containing instructions for the preparation of theriac. The complex electuary originated as an antidote to poisonous bites from wild animals (theriakos) and was supposedly homeopathic in nature, as it was widely believed that snakes contained an remedy that prevented them from being poisoned by their own venom. Theriakos, ‘of a wild animal’, derives from the Proto-Indo-European root *gwer, which also gives us feral, fierce and ferocious. Greek theriake contorted through Latin, Vulgar Latin and Old French to arrive in fourteenth-century England as treacle, where Italian theriac, sweetened by its honey excipient, began to be marketed as ‘Venice Treacle’. Potnia Theron, mistress of animals, shares this bestial etymological root.

Preparation of viper flesh for Theriac, Hortus Sanitatis, 1491

When the Greek physician Galen used and adapted Andromachus’ recipe for theriac, he wrote that his predecessor had chosen to document the cure-all in verse because it is more memorable than prose. The notion of poetry acting as medicine’s sweet excipient recalls Lucretius’ explanation for using verse to convey Epicurean physics and philosophy in De Rerum Natura, which compares poetry to honey lacing the lip of a cup of bitter wormwood, then used as medicine for a variety of maladies:

. . . I write

Of so darkling a subject in a poetry so bright,

Nor is my method to no purpose – doctors do as much;

Consider a physician with a child who will not sip

A disgusting dose of wormwood: first he coats the goblet’s lip

All round with honey’s sweet blond stickiness, that way to lure

Gullible youth to taste it, and to drain the bitter cure

For Galen and Lucretius, literary palatability is the means by which hard truths can be imbibed. Prosodic and poetic features, like the brigata’s cyclical doses of narrative, are supposed to act as the saccharine carrier for what Lucretius terms the ‘bitter pill’ of philosophy. The brigata’s fragrant garden is the world-as-pomander, in which the characters’ sickly love songs drawing each day to a close echo Lucretius’ desire ‘to coat this physic in mellifluous song’.

Except it is too easy to leap to splitting here, to suggest that poetics and narrative are a sugary escape from the bitter scientific ‘reality’ of the plague and its fetters. Like the snakes said to contain an antidote to their own poison, Boccaccio’s use of narrative in relation to the plague functions more like a pharmakon, that indeterminate admixture of remedy and poison. Jacques Derrida describes the pharmakon as an ‘ambivalent’ figurative space, the ‘locus of play’ in in which opposites mingle without being reduced to binary oppositions. Like Beritola’s island that is both haven and lazaretto, and Fortuna’s omnipresent gaze that both weeps and twinkles, The Decameron’s narrative conceits elude the interpretative violence of fixing things as one or the other.

A few weeks on from locking eyes with Kiki Smith’s doe I meet Fortuna in another guise. The new decade has begun, and I am five months back in the city I left over two years previously. That was to move to the other city, a city I knew well because I had studied in it, a rushed and difficult move for the relationship whose spicules I am still trying to dislodge from my skin. The emotional geography (and economic hegemony) of Scotland’s central belt is such that in whichever of its two cities you reside, Glasgow or Edinburgh, the one you don’t live in becomes the ‘other’ city. So much so that when I left my former home last summer and spent some weeks staying with friends, one of them, who has lived in the city for over three decades remarked, ‘That’s the great thing about Scotland. When everything goes to shit in one city you can just hop over to the other one and disappear for a while.’

The summer I left, last summer, marked a year’s anniversary since the Dutch-owned Scotrail franchise introduced a new fleet of electric trains, Class 385 Express, which took the nearly hour-long rail journey down to 42 minutes. When I lived in one city and taught in the other, this journey was my commute. Now I live in the other city and only go back when strictly necessary; the former city is now associated with unpleasant but necessary tasks and meetings – with the Citizen’s Advice Bureau, with lawyers and estate agents, with depositing or uplifting possessions. I notice that as the train gets closer to arriving at this city’s main station, my muscles clench, my breathing constricts. I have even developed a somatic response to the particular beeps and dingles emitted by these trains’ announcements and automated doors. Mostly I find myself staring out of the windows on such journeys, a screen of untouched admin in front of me.

Exactly two hundred and fifty summers before last summer, while looking for stone to construct the nearby Forth and Clyde canal, some workmen found the remains of Castlecary Fort, a Roman settlement built along the Antonine Wall in the first century ce. Among the various votive altars and distance markers they also found a small statuette carved from the local sandstone. It appeared to be a robed female figure with an unusually direct gaze, holding what looked like a horn in one arm, and a wheel attached to a stick in the other. In Castlecary, just a stone’s throw from the artery of the central belt – the Glasgow-Edinburgh main rail line – they had found Fortuna.

Fortuna with wheel of fortune and cornucopia

I visit the Hunterian museum on a rainy day. I have been to the museum several times before, but for some reason have never been drawn to the exhibition – concerning Roman Scotland – that is straight ahead when you walk in. Instead I have gravitated to corners, where William Hunter’s shrivelled anatomical specimens linger in discolouring turpentine, and bird nests are trapped behind glass. On this occasion I walk straight ahead, eyes peeled for the goddess. When I find her, I have an inexplicable urge to laugh. Perhaps at myself, at the narratives and para-narratives involving this figure I have woven over the last few months.

Fortuna stands snug in her niche, mounted roughly at my eyeline in too-bright uplighting. Her stance is somehow both slant and erect, slouched and determined; the phyllotactic spirals on her tunic and cornucopia run away from each other in opposite directions. I try to make out the two-faced gaze, the weeping eye and the twinkling one, but the red sandstone – which I cannot disentangle from the sandstone tenements I have lived in my whole adult life, in this city and the other one – is too worn away to discern. Behind her, through the Hunterian’s latticed windows, are grey skies and the greyer grey of the hulking university library. I imagine Fortuna’s gaze looking out over the central belt, and I find myself silently telling her that next time I am on the train, from this city to the other one, I will think of Vortumna, she who revolves the year, of The Doe and the mistress of animals, and pay my respects.

Feature artwork © Kiki Smith, Fortune (detail), 2014

This essay is part of a longer work-in-progress, Lovebug. An alternative version is forthcoming in ON CARE, published by Ma Bibliothèque.