‘Now we toast Lenin!’ declared Jameel Abu Jabel, rising from a table spread with salads, shashliks and drinks. His Syrian comrades raised their glasses and shouted, ‘Lenin, da da da!’

The sun outside was melting over the Golan Heights, spilling its golden glow over apple plantations and minefields. I downed my shot for Lenin and chewed my shashlik.

It was 2009. I had traveled from Egypt to Israel, and was now raising toasts with comrades, just like my father had when he ventured behind the Iron Curtain in 1982. ‘We are the products of the Soviet-Arab alliances,’ I explained to my festive companions.

Sixty years ago, Syrian president Hafez Assad and the Egyptian Gamal Abdel Nasser had signed arms deals with the Soviets and toasted lasting comradeships. They needed weapons for an imminent war with Israel. On a grander scale, the USSR built alliances with the newly-independent Arab states, strategically countering the US, and invited Arab communists to study in Soviet institutions – my father was one of these. He was put on a boat from Alexandria in Egypt to the USSR by my communist grandfather. A decade later, Jameel and his Syrian comrades had left the Golan Heights, also to study in Russia.

The village where we were, Majdal Shams, had a lethal legacy underneath its apple orchards, and no one knew this better than my comrades. When they were not toasting Lenin or Nasser or Bashar Assad, these men cleared landmines. There are said to be thousands of them scattered around the village, some are Syrian and others Israeli, planted after the1967 war between Israel and Syria, Egypt and Jordan.

The war ended with Israel occupying former Arab lands, including the Golan Heights in Syria and portions of the Sinai Peninsula in Egypt. Egyptian president Anwar Sadat eventually signed a peace treaty with Israel in 1979, that led to Egypt reclaiming the Sinai. That cost him his life, Sadat was shot by vindictive Islamists in 1981. That same year, Israel formally annexed the Golan Heights. Many Syrians crossed the new border to their homeland, a few like Jameel and his comrades remained. The two states remain at war to this day.

After emptying a few bottles, we drove off to explore the minefields. Jameel’s car bumped along dirt tracks between orchards and passed a yellow sign reading danger! Mines! When we arrived, I followed Jameel and his comrades through the deadly minefields, tipsy and doing my utmost to keep my balance for the sake of my well-being and, well, my pride. The comrades, on the other hand, marched unfalteringly. I climbed on top of a rusty bunker and looked out at the mountains: Syria was just a few kilometres away. But there was little chance that my comrades would return to their homeland any time soon.

Among many other things, my comrades explained to me how their fight against Israeli oppression led them to discover communism. Now, however, they’d more or less given up on the class struggle, at least in a political sense. Landmine clearance sessions and nights of drinking and toasting communist leaders was all that remained. I told them of how I enjoyed Soviet parades back in Moscow. And how my father raised toasts with his comrades. I even told them that it was not his choice to leave to Moscow. What I did not tell them is that my father was ill.

Just before I left to Israel, my father had been diagnosed with kidney failure. When I returned home, he would show me a Hemodialysis fistula on his left arm, along with puncture marks. He had been rushed to emergency while I was away. Now he had settled into a routine of blood filtering, twice a week at a hospital near Alexandria. I told him about the comrades I met in the Golan Heights, and wondered what he thought. My father was always a private man. He wanted to protect, even tactfully control, his daughters, especially after 2001 when we moved to Egypt – to his domain. In response, I wanted to establish my own independence.

As he got ill, he began introducing moments of glasnost into his relationship with us. Still, telling him in his fragile state about how I, his daughter, had left home to visit foreign – and in his view hostile – lands, upset him. Only later would I know that he took the articles I was writing about the Syrians for Egyptian publications, and showed them off to his little entourage at the hospital. It was his way of expressing his pride in his daughter.

*

Hassan – my father – upset his own father. He had had a scandalous affair with a Christian woman as a young man. This partly why his father sent him away to Moscow. At that point, Hassan was not a communist per se – he was more of a charmer, the singer in a band called Diamond. My grandfather Abouissa thought his son would get over the woman, study orthopaedics for a few years and then return to Alexandria to take over his shoe shop. But Hassan would not follow in his father’s footsteps.

Then (as now), Egypt was ruled by army-bred leaders. When Hassan was born in 1952, Gamal Abdel Nasser and his Free Officers toppled the British-backed monarchy, and took power. Nasser allied with the Soviets, who helped him to build the Aswan Dam and factories, as well as supplying arms for the fight with Israel. His successor, Anwar El-Sadat, expelled Soviets from Egypt and turned to America for assistance. After his assassination in 1981, he was succeeded by Hosni Mubarak, a Soviet-educated MiG pilot. Though the three all had different views on the USSR, they were equally autocratic, and equally suspicious of any organization which might threaten their power. Under all of them, Egyptian communist organisations were illegal.

So when Hassan left Egypt for Russia in 1982, his trip was clandestine. Egyptian communists who traveled to the USSR were supposed to supplement their studies with ideological programs. They were to absorb communism and return to support the underground communist factions in Egypt. Hassan, on the other hand, supplemented his studies by making a living off the socialist economy; he was a dealer in hard currency and other foreign treats – a ‘suspicious man’ with connections, as one comrade remembered him. He was a man of natural-born craftiness – a skill mandatory for survival in Moscow at that time. Whatever else he did, he was also a comrade, attending Arab communist conventions and toasting the dead leaders.

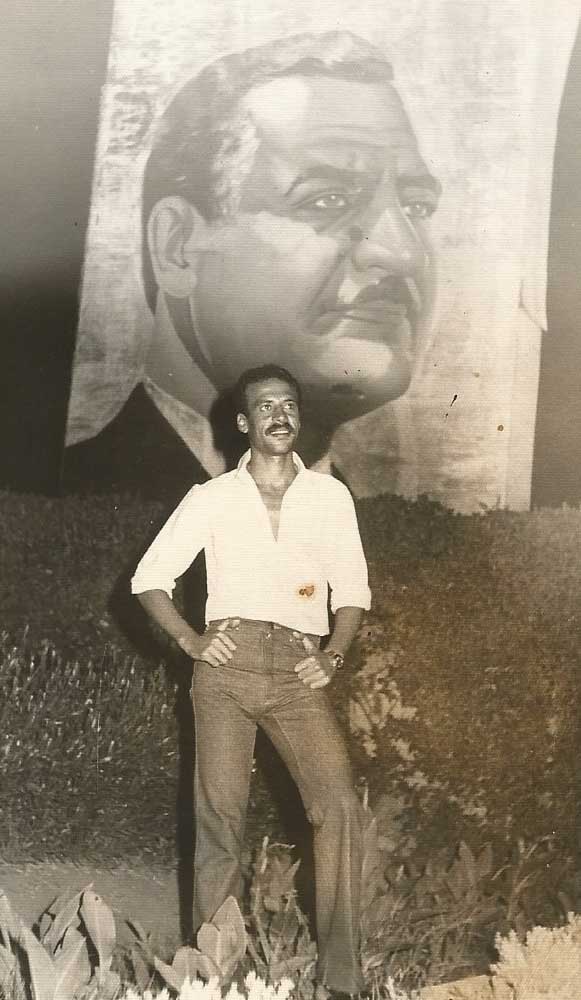

Hassan Abouissa

I grew up as the Soviet Union was collapsing. I remember watching kooks on TV asking viewers to fetch jars with water to help transmit their healing energy; churches packed with worshippers; waving a red flag at grand military parades showcasing Soviet might (I loved that). I remember my first day at the only Arabic school in Moscow at that time, where I spoke no Arabic and understood nothing (my father insisted we receive an Arabic education). And Lenin’s dead body – I understood he was an important man (he had his own pyramid and disciples queuing outside) but I was too young to comprehend the body lying in front of me. Most of all, a year before the USSR collapsed, I remember the first McDonalds opening in Moscow and attracting longer queues than Lenin’s Mausoleum. Since then, hamburgers have always reminded me of those last days of the Soviet empire.

*

By 2013, my father’s disease had been progressing for four years. It now affected his lungs and his heart. Some mornings I found him nauseous. It was difficult for everyone, especially my mother. I was living in Cairo and whenever they rang me, my heart sank. I knew I was running out of time.

Then, I found a photo online. A group of sweaty men waving huge red flags in Tahrir Square. Egyptian Communists. And at that moment, like the alignment of stars in constellation, I knew I had to meet them if I wanted to understand the ideology that underlay the surreal experiences I had had as a girl. And by doing so, I thought I might understand more about the man my father was.

*

It was that hot summer I first climbed the four flights of stairs to attend a meeting of the Communist Party in downtown Cairo. The Muslim Brothers – the communists’ nemesis – were running the country. In late 2011, the Brotherhood had won the majority of seats in parliament. And in 2012, one of them became Egypt’s first democratically elected president. The communists, on the other hand, did not partake in those elections. Unlike the large numbers of God-fearing followers of the Brotherhood, they did not have a distinctive party platform or funding. They did what they do best – plotted and protested. I arrived at a time when things were getting ugly for the Brotherhood.

The country was split between Islamists and the rest. Weekdays were more or less normal, but weekends promised bloody clashes, gunfire and public funerals. The country lost its balance, swapping its statesmen and policies like acrylic nails. Little things made sense; a juice vendor that continued to work, the highway to my family’s house in Alexandria that remained safe, evenings with circus performers talking about their lions and scars (I spent most of the 2011 aftermath at the state circus working on a story). Downtown was the centre of it all – the battlefield. I usually stayed away, but not today.

On my way up to meet Egypt’s communists I passed dingy flats converted into offices for lawyers and programmers and salesmen – little did they know they had a former enemy of the state living above them. Inside, there was a little kitchen where daily tea was prepared (alcohol was not allowed), and an office where Essam Shaaban, the Party’s spokesperson, worked on his thesis on Egypt’s endemic poverty. Essam was my age. I also met the Party’s secretary Salah Adly, who was my father’s age and placid like a panda. Salah introduced me to the circle of comrades: ‘This is the granddaughter of comrade Abouissa.’

He explained that when he and his comrades were young partisans (around the time my father was singing James Brown, breaking a heart or two), the headquarters were camouflaged as the Center for Socialist Studies. In the cafe downstairs, secret police used to sit smoking shishas, watching comrades go up and down the stairs. The meetings were arranged clandestinely through leaflets printed and circulated by junior comrades. In Cairo, young Salah used to spend his evenings sweating over a Roneo printer, while in Alexandria my father distributed the leaflets on my grandfather’s orders.

Only a few were entrusted with the location of their mentors’ hideouts, and even then only code names were ever used. They were arranging workers’ strikes against Sadat’s capitalist elite, and in return the president dispatched police raids on their homes and meeting places. On May Day 1975, fifteen police cars surrounded the Cairo centre looking for Salah and his Roneo. He escaped, though many of his comrades were arrested. There, in prison, the comrades declared the official formation of the Communist Party of Egypt – an anniversary celebrated to this day.

‘It has been a while since I last saw this symbol,’ I told the gathering, pointing to a large red poster where a hammer and sickle stared down at me. ‘It reminds me of my childhood.’

They told me about the major role the communists played in Egypt before 1952, before being excised from history books.

My father had met some of their leaders when they visited Moscow, I told them.

‘One of the lucky ones,’ the comrades said about my father, because he not only traveled to Moscow but married a Russian. As I was about to leave, an elderly comrade poked my shoulder and said, ‘You are the third generation – you continue the legacy.’

Suddenly I was not a mere journalist, but a sputnik of their system. ‘Thank you,’ I replied.

*

As I dug into the history, I discovered something interesting: the legacy of Egyptian communism was established in the forties by a group of young Jewish men. They were born in Egypt to parents of foreign lineage – Italian, Russian, Greek, Syrian – who migrated to the British colony and prospered. Raised in gated communities and attending foreign schools, they spoke little Arabic, and one of them, the son of a banker who deeply opposed social injustice under the occupation, became a Marxist. His name was Henri Curiel, and in 1947 he founded Hadetu, which would become the largest nationalist Communist movement of workers, intellectuals, young partisans and even Free Officers.

But after the establishment of Israel, anti-Semitic debates tore Hadetu’s politburo apart from the inside. Arab members challenged the Jewish leadership, wanting to follow the USSR in their support of the partition of Palestine. When Nasser took power, he expelled foreigners and Jews, including Henri and other Hadetu leaders – of the Egyptian communists that remained, many were sent to prisons and labor camps for years. Some of them never left.

Despite this being the most difficult period for communism in Egypt, the older generation of communists I met in Cairo – party secretary Salah among them – saw a greater, socialist good in Nasser. The president had sealed an alliance with the USSR and, though he hunted communists, also adapted socialist principles in rebuilding his state. Today, Salah and his generation remembered Nasser more fondly than Henri Curiel himself. As for Salah’s mentors, my grandfather’s generation, they now attended each other’s funerals rather than communist conventions. There are only a few left who bother climbing those four floors to attend party meetings.

*

My father was excited to hear about my visit to the communists. He was not a communist anymore, but like them he was a Nasserist. He too found the Muslim Brothers intolerable and, like many former communists his age, would rather support the system he knew best – the military.

After his dialysis sessions, he’d take his meal in front of a TV show and digest it along with violent news footage and fist fights in the studios (the fights were the best). He had a favourite anti-Islamist presenter, a pneumatically-carved woman with the hair of a mermaid. He would call me saying, ‘Come and see what my bunny is wearing today.’ But whenever an Islamist appeared, he spat at the TV screen.

My father created his own front in the dialysis ward in Alexandria, while Salah’s comrades protested in Downtown Cairo. He had a little group of followers who hung on his every word. He spoke to them of excess water in their bodies, cooking and politics, as their blood ran between hissing machines and their pulsating fistulas. He also brought in my articles – without me knowing – to show off. They addressed him as doctor, a title he granted himself since he had graduated from a Moscow university. He had lost his business to the global economic crisis, and his health to high blood pressure, but he never lost his charm.

I promised both my father and his estranged comrades that I would reunite them. Maybe he would find their cause more appealing now, I thought. Maybe joining the comrades’ front would make him feel he was in control of something greater than himself, more than just a frail body hinged on a dialysis machine.

*

Everything changed when my father began dialysis. He closed his eyes as the catheter punctured his neck: he loathed needles. More than anything, he hated sharing his father’s fate – grandfather had died of kidney failure.

My father was away when it happened. I attended the funeral, everybody cried, many of them people I did not know. My aunt pulled me through the crowd so I could have a last glimpse of my grandfather before his shrouded body was placed in the family’s tomb. There was a faint smell of decay. I did not see much, and I did not cry either. One thing that struck me, however, was my grandfather’s clock. It stopped on the hour he died.

For the other patients behind the curtains where my father lay, dialysis was already routine; they slept, read or chatted as their machines hissed and beeped. This machinery of filters and pumps and tubes weighed more than my father did, there to replace his little kidneys. He threw up.

My father’s life was organised around his dialysis sessions, and I realized I would not be able to take him from Alexandria to visit his comrades in Cairo. Instead, we stayed put and followed a strict diet: less fish, no bananas, dairy products or his beloved old peasants’ cheese. My siblings and I learned to detect the warning signs, as he rarely complained. When I noticed him nonchalantly clearing his throat, I’d place my ear on his bony back to listen to him breathe. If there was a gurgling sound, we had to be ready to take him to hospital.

During the tectonic days of 2011, when Salah, Essam and their comrades did what their mentors never managed – raising red flags and communist banners in public – my father faced his own struggle: the doctors had discovered cancer in his lungs. His Russian connections landed him in the care of giggling nurses and the best specialists at Moscow’s top cancer research centre. He spent his fifty-ninth birthday on the operating table. He was in pain, a tube with a drainer connected to his lung, his chocolate skin tightened around his emaciated physique.

The doctor allowed him to have a few last cigarettes before this epic abstention.

‘Then I shall!’ he smirked and dragged his drainer to the balcony. I watched him sending smoke over the capital that had changed his life. He was still the most exotic man there.

When we returned to Alexandria, the family went to the beach. My father plunged into the sea, slicing through the waves – I could still see the dark incisions where tubes had pierced his skin. He was invincible.

I told him that I had been called by his comrades to continue the legacy. It made him smile.

*

‘Long live the proletariat!’ shouted a wiry comrade.

‘Long live the proletariat!’ the crowd roared back.

‘The Islamists want us to kiss their feet! We say NO!’

The comrades shouted, capillaries throbbed on their faces, sweat soaked their shirts and onlookers stopped and stared. The TV vans followed them patiently, avid for action as we approached each riot-police cordon. After the 2011 revolution, a multi-party system was introduced, and the Egyptian Communist Party was no longer illegal. This 2013 protest was the second May Day they were able to actively take to the streets, rather than hiding inside their camouflaged headquarters.

Salah was shouting beside me, though he still seemed as placid as a panda compared to his fiercer comrades. He had not always been so panda-like. Before he went low-key, working with a Roneo, he used to fight armed Muslim Brothers on university campuses. Something that the secretary later recalled with a mischievous smile.

I waved a red flag again, just like I had when I was a kid at the Kremlin’s military parades. It was something innate, like the taste of ice cream with chocolate flakes or the smell of incense of a neighbouring church: something that brought comfort. Even the secret policeman who was watching did not bother me.

We outflanked the malnourished policemen and entered Tahrir Square, deserted and stripped of greenery. Under martyrs’ memorials, shady street vendors had set up their wares. They had crept from the darkest corners of Egypt, struggling with unemployment, and were selling tea, gas masks, Egyptian flags, political memorabilia – all depending on whether the public was after blood or celebration. A tea-boy fired his gun into the air on our arrival.

*

Salah and my father’s generation were born into a post-colonial nationalistic euphoria, and educated in Nasser’s ‘intellectual temples’, as they called them. They found answers to life’s questions in Marxist books imported from the USSR by Dar Thakafa Jedeeda, a socialist publishing house often raided by police. In the seventies they joined underground cells run by Hadetu elders. Salah and his contemporaries lived double lives – university students by day and partisans by night.

‘Since I was eighteen I was asking why there was injustice, wars, poor people and rich people? I wasn’t convinced it should be this way. I looked for answers. If God exists, how does his religion allow injustice?’ Salah asked me.

I noticed the comrades were careful about their religious stance: I never heard them denouncing God, but I understood they, like any communists, had a complicated relationship with Him. That was their greatest obstacle in a majority Muslim society.

‘Lenin shifted my life, convinced me that I should belong to a party, while Marx overturned my thinking,’ Salah said.

He had been in charge of one of the Roneo printers, which sustained the Party’s communication network. It was as influential as Facebook was in 2011, and just as the authorities had tried to curb those protests by cutting the internet, so back in 1952 the Free Officers confiscated Roneos from communists. In 1981 a Roneo landed Salah in jail. He faced twenty years in prison for ‘sabotaging Sadat’s state’, but was given three years by a sympathetic judge. He served a year and was released with everyone else after Mubarak took the presidency.

*

As I was raising flags in Tahrir Square with Salah, my father was in a Moscow hospital again, this time with a collapsed lung. Through Skype I had told him that grandfather was going to be honoured among other elder communists, and I was going to receive the certificate on his behalf.

We gathered at the party’s rental-flat-cum-headquarters, where elderly communists of my grandfather’s generation had arrived from different cities. Salah thanked them for coming, then spoke of how the Egyptian media was purposefully hiding history – their history.

Hamdi Hussein, a small but fiery force of nature, sang the national hymn: ‘My country, my country, you are my love and my heart.’ We all stood and sang along. Then comrades took turns speaking about the mentors who had helped them study in prison, to organize student demonstrations or complete undercover work. They had grown up together, were recruited from the same student unions, inspired by the same books, and knew one another’s secrets.

Songs about comradeship and struggle blared in the background, some of them by a renowned proletarian composer who had rocked my sister Anjelika when she was tiny in Moscow. I felt among family. Names were announced for awards and certificates – though most of the prizewinners were no longer among the living. At the end everyone chanted at the top of their voices, ‘Long live the communist’s struggle!’

These comrades had only heard of my grandfather, how he was arrested back in Alexandria in the seventies, the neighbours saluting him as police escorted him away. My grandmother used to have to hide their money so he wouldn’t give it to the party. My father told me he was a good man – too good. Holding this certificate was as close as I’d ever come to knowing him.

‘As soon as you get back from Moscow, I will bring it to you, we can put it on the wall,’ I told my father. He smiled at me through the computer screen. But I would never have the chance to show it to him.

*

What I remember most about my father is how he was before he travelled on his business trips – selling Egyptian crystal chandeliers, or carpets or tourism packages or Siberian timber. My mother would help him to pack, and then we always kissed him goodbye. And then the excitement when he returned.

The last time I saw him, he was traveling to Moscow again for treatment. I hugged and kissed him as always, and he was driven away. When he passed away, at night in the house he built, I was not there. My mother called me at four a.m. and said it was quick. I did not cry or panic – I had to deliver the news to my young brother, who was with me. We went to see the sunrise and there was nothing natural about it.

It was only four days later that I cried. I felt then – and still do now – that I had been left to put together the pieces of his last days, like a forensic scientist trying to construct some kind of closure. For me, he is travelling on his last trip, while I have been left here with earthly sunrises and Egyptian communists.

*

‘That’s it! That’s it! I will start hitting people!’ Hamdi Hussein shouted, a workers’ representative who now turned into a little ball of fury. He had fought off police in workers’ strikes, the Israelis in 1973, and now he was ready to fight a ‘djin’ himself if anyone interrupted him, bug-eyeing the rest of the young comrades. It was the summer of 2014 and the communist convention was descending into acrimonious dispute.

The old and young reared, pushing chairs over, plunging and grabbing each other, spitting out accusations of Islamist treachery and military infiltrators. ‘I organised this meeting, do not speak to me this way, shut up! Shut up!’ shouted Essam. They were fighting about the party’s vote on Egypt’s new president.

My foot was trapped under Salah’s bulk as the secretary rushed to unlock comrades. The end of the Muslim Brotherhood’s reign was ugly, with street wars, constant fires and public funerals. The Brothers became hunted terrorists overnight, a device used to justify the return of the generals. Abdel Fattah Sisi was the front runner, the former chief of military intelligence who played a leading role in ousting his predecessor Mohamed Mursi. Mursi was sent to prison where former president Mubarak had also served time. Salah, Hamdi and the other communist elders saw a reincarnation of Nasser in Sisi’s rhetoric, his calls for a war on terror. The young comrades feared the army’s iron grip, and supported the civilian politician Hamdeen Sabahi.

‘What’s this? It’s impossible,’ murmured Salah, releasing my foot and passing through grumpy comrades. Secretly, he feared an internal split.

Essam retreated into the kitchen. Back in the nineties, Essam grew up with Islamists in Upper Egypt. He would cycle kilometres to local book fairs looking for communist literature. And in 2004, Essam, an experienced activist with an arrest record, joined the party. ‘It was all elders, they hadn’t recruited youngsters in years,’ he told me. But now he was doubting his decision, quietly smoking away the tension in the kitchen.

‘The connection with the current generation is lost,’ Bahiga Hussein, the petite journalist wife of Salah, complained to me as we sat at the party’s office downstairs. ‘Our elders handed their experience down to us, we respected them, visited their hideouts, but this generation . . . I do not want to speak about it.’ Bahiga blamed Mubarak for scrubbing political life away, blamed the youth for their indifference, and blamed the rest of us for forgetting their struggle.

In the headquarters upstairs, giggling young comrades were speculating about how long Bahiga’s rant would go on. Since the revolution, the younger generation had been demanding more recognition. Their elders felt forgotten. Bahiga lamented that the young thought they had accomplished what her generation couldn’t – ‘Not true,’ she countered. ‘We never left the squares.’

Essam told me that the 1940s generation had ‘the true spirit of struggle’, that their disputes were political rather than personal, unlike the 1970s generation. For them, the socialist dream was flagging. They would rather settle for Sisi’s promises than struggle.

‘Lets have an open vote,’ Salah suggested. ‘I think it’s the most elegant stance, and the cafe needs its chairs before the match. Who is with and who against?’

In the end, the majority decided the party would not take any stance on presidential elections. The comrades collected the chairs, and the young and old alike chanted, ‘Long live the Egyptian communist party! Long live the struggle of the proletariat!’ under the red posters inscribed: ‘Socialism is the future. We build it together.’

That day, however, the only thing the two generations really had in common were their moustaches. I thought of my father. Would he have plunged into battle, or mediated like Salah? He had passed away a year before this fight. After his death, I took some time out from the meetings. When I eventually returned to his estranged comrades I explained why my father would not be coming back to join them. Their cause had changed my father’s life, and if he was not always a part of it, it was a part of his life. And maybe that is why I returned.

*

‘How can a party not decide on a vote?’ Ahmed Kassir, a veteran from the Hadetu days, complained to me a few months later. ‘I know what happened. They had a fight, then they took votes, and the majority voted for Sisi – but now the minority wants to hijack the voting and declare a free vote.’

He was showing off, letting me know he had spies everywhere. I told him that wasn’t exactly what happened, that I was there. He kept telling me he knew better.

It was a hot June day in 2014, and Egypt had just elected Sisi. The air smelt of gunpowder. Army tanks and barbed wire had isolated Tahrir square. Downtown started to crowd with loud masses celebrating, and vendors laden with Sisi memorabilia had taken to the streets. Music vans patrolled the streets, overflowing with grooving boys and gyrating, ululating women. Fireworks exploded overhead. In three years of feasts and fights I had learned to distinguish fireworks from live ammunition.

In a coffee shop frequented by old comrades in the heart of the celebration, skeletal Ahmed started telling me of another ‘party’ back in 1960. ‘I saw him naked thrown on the floor, but I couldn’t tell if it was Shohdi or Fawzy, because of all the blood.’

Just before I met Ahmed, someone else had told me about the same event. I had gone to a publishing house that used to smuggle Soviet literature back in the day, and met with renowned author and communist veteran Sonallah Ibrahim. Both men, now in their late seventies, took part in that ‘party’; one was tortured and the other was ordered to watch.

‘After a trial in Alexandria, forty comrades were taken to Abu Zaabal prison,’ Sonallah remembered. ‘ “Get down!” they told us. We obeyed. “Sit, you dogs! Heads down!” We sat.’

Wild-haired Sonallah re-enacted the scene, crouched on the sofa, veined hands collected between his legs, head down. ‘“Stand up! Run! Run!” We ran.’ As he ran, he was chained to Shohdi Ateya, an editor of a Hadetu newspaper who gave him his first journalism job.

‘We ran through the army’s human corridor. They all had different varieties of truncheons, tchik tchik,’ Sonallah pummelled the air with invisible truncheon, ‘it was random beatings. Then a horseman summoned Shohdi and took him away.’

The ‘reception party’, as the officers called it, went on for hours. After the beatings, the detainees saw a prison committee where they were stripped, shaved and tortured, except for the four men ordered to watch. Ahmed was among the tortured, and Sonallah was among the watchers.

Later, the watchers too were stripped, shaved and dragged across the floor. ‘I went inside a cell and saw my mates all confused, blood running down their backs, and there was one who kept saying “birds, birds,” staring into space,’ Sonallah remembered.

The next day, Sonallah and another man with less bruising were ordered to testify that Shohdi had died on the road. ‘I would say whatever they wanted – I was in nervous mental paralysis.’ In Yugoslavia, in front of Tito, Nasser was asked by a reporter about Shohdi’s death. In response, the president immediately ordered an investigation, which was why Sonallah and the others had been called to testify at all. Still, after the coverage, the torture of communists stopped in Nasser’s prisons.

Sonallah was arrested drunk on the first sunrise of 1960, along with 500 other communists. ‘Nasser’s New Year’s gift,’ he called it. At that point he had left his job to become a ‘professional revolutionist’, spending nights with a Roneo in communist secret cells, just like Salah would a couple of decades later. In prison he wrote a novel about prison torture and sex, all on cigarette paper that he managed to smuggle out. That Smell was published twenty years later, by the same publishing house we were in now. Critics worldwide called it both ‘filth’ and ‘a masterpiece’.

After the torture ended, the prisons became communist cultural hubs, filled with banned books. The comrades could read, paint, even put on plays for prison officers. That was how authors like Sonallah were born.

‘The worst thing that could happen to a communist is to be deprived of the opposite sex for a long time, or to have his ideological foundations destroyed – that is what Nasser did with his social reforms, he pulled the rug out from under the communists,’ said Sonallah.

When he and many others were released on Khrushchev’s visit to divert the Nile for the Aswan Dam in 1964, they found no reason to keep fighting. Nasser had adopted their socialist reforms. Many joined his Socialist Union, hoping to change it from within. Ahmed, who always sought frontline action, went underground, regrouping and resurfacing to oppose Sadat’s capitalist reforms. Sonallah left for the USSR to study filmmaking and build a new life.

Sonallah’s and Ahmed’s generation, my grandfather’s generation, is a dying breed. ‘I have just a few years left, and I would rather spend them writing,’ Sonallah told me. For another two years, Ahmed relentlessly fought old battles, as well as new, in his books and on his Facebook wall – where he proclaimed that Hadetu was betrayed by the left and that the young revolutionary front was filled with foreign agents and terrorists. Until one day a stroke paralysed the old communist putting an end to his battles. He died alone in a dreary retirement home.

*

My last rally with the comrades was on May Day 2014. The slogans had shifted from ‘Communists till death’ to ‘Down with the military regime’. It was a smaller and less united rally than the one the year before. We were just a few young Trotskyists from the Revolutionary Socialists and the Egyptian Communist Party. Another three leftist parties from the newly-formed Coalition of Socialist Forces were absent, although Salah had invited them. I asked Essam why they had chosen to demonstrate anyway: ‘So people know we exist.’

Salah and his contemporaries frowned and left the rally to the anti-military youth, and we all headed off to get a beer. It was the Egyptian Communist Party’s 38th anniversary, and I was glad to be drinking again with comrades.

‘Prisons were good because we could all meet, we could not do that outside,’ the older comrades reminisced. This pub in particular had also became a hangout for them: ‘We had policemen waiting for us outside the bar, we felt sorry for them and asked them to join us, but they did not, they were religious,’ one comrade cheerfully recalled.

Essam didn’t stay long. Back at headquarters he was urging a new wave of young communists to solidify their position and lead grassroots action. ‘We cannot be ignored in the party,’ he kept telling them.

I watched him speak, but couldn’t help feeling that this generation, the post-2011 youth, was confused. Salah and his comrades had the legacy of Hadetu and Nasserism; Ahmed and Sonallah had the Soviet Union; but Essam and his comrades were born into a peaceful political void; they had to build their own dreams of a socialist paradise out of nothing.

It was the Party’s last May Day demonstration.

*

Throughout my time with them, the comrades would speak of an old curse on them. Usually with irony. A curse that kept them divided, prevented them from prevailing over the capitalists who ran everything from their factories to the borders. If they weren’t debating over Marxist rhetoric or cross-examining each other’s degree of leftism, they were waiting for another Nasser. They never united, never came up with a grassroots action plan to guide the masses.

What they had in common was also what alienated them from the country – the catatonic state of their socialist dream. Their cause, as eloquent and valorous as it was, could not succeed, because it was in a constant struggle with its own reflection. And maybe that was why my father stopped attending their meetings and moved on. He was not romantic enough.

*

I visited my father’s grave only once. I never managed to reunite him with his old comrades. He shares it with his favorite uncle and his father Abouissa. The cemetery was naked of any greenery, and was only distinguished by poles with hand-written signs rising from the sand, planted by those who had bribed the undertakers to indicate where their loved ones lay among the gravestones’ cluster. Many of these, like my father’s, are shared graves. As we stepped inside the cemetery, a gang of scruffy undertakers surrounded us like vultures, asking for money to help us find our father’s grave. We navigated the gravestones, hopped over debris, searching until finally we found it. One undertaker pulled out what little was left of the greenery surrounding another grave and stuffed it on top of our family’s gravestone, another fetched water from nowhere and splashed it onto our distressed plant. Then the whole gang started chanting verses from the Quran for my father’s soul. We stood watching their choreographed performance. At the end, my sister Anjelika unzipped her pouch and they all jumped at her, pecking for the money.

I still visit his former comrades. Recently they celebrated the fifth anniversary of the revolution. They spoke out against the Rightists in the current parliament, against the continued power of Mubarak’s former henchmen, and against the rising tide of terrorism. The main purpose of the convention was to unite the feuding Leftist fronts in the hopes of becoming a serious political force.

One comrade stood up and said, ‘We deserve this defeat. Where is the movement that stirred Egyptians in the seventies? We were able to move streets, our generation! The left in its current state is not ready.’

Salah was busy with his speech notes, scribbling new prophecies for the party. Hamdi, zealous as ever, sang a hymn at the top of his lungs and we all joined him. There was no Essam. He had left the party and shaved his moustache, joining the ranks of the feminist lobby, many of whom were as old as his communist mentors. I asked him if he was still a communist.

‘Yes, I still hold communist beliefs, but I can’t be in a party that doesn’t share them,’ he replied. I thought that if the communists ever want to achieve their socialist dream, they needed to stop looking for Nasser’s ghost – to lay their dead leaders to rest.

As for my father, I was gradually realising that he had never inherited the socialist dream, although it had changed his life. He was an opportunist (his comrades might even say a capitalist), skilful and charming, who used his time in Russia to build a timber business, trading Siberian forests to Egypt. He built a house back in Alexandria and moved us into it, uprooting our lives, just as his father did in sending him to Moscow. I told him just before he passed away that he did the right thing. He may not have been a good communist, but he was a good father.

There are things I regret. I regret not being able to contact Jameel, to make sure he is still toasting the dead leaders with his comrades and has not accidentally tread on a landmine. I wish my grandfather was still alive, to fill in the gaps of this story. And I regret not talking to my father more when I could. In the end, all this was not an effort to continue my comrades’ legacy, or my family’s. It was a way to bid farewell to my father.