My first encounter with Barongo Akello Kabumba, the other African on the programme, was a disaster. It was at the welcome party, attended by the programme team and affiliated faculties from departments across the college. Barongo Akello Kabumba had introduced himself with all three names, as if to stress his authenticity, and he had shot me a curious look when I introduced myself, repeating my name back to me to press his point. ‘No native name?’ he asked, adding to the irritation that had been building up in me since I saw his profile on the programme website, where his massive smile and Maasai toga contrasted with my black and white portrait in the same corduroy blazer I always wore on special occasions.

It never occurred to me, not even once, that Kabumba and I could be friends. There was something about him that ticked me off.

He had the same Maasai toga at the welcome party, and this time he had a stick – a damned cattle-herding stick. How he got through customs with that weapon remained a wonder.

Grinning from cheek to cheek, offering slight bows to everyone, he was the centre of attention at the party. There were always at least three people chatting away with him, listening as he gesticulated with one hand, holding out his stick with the other as though to hurry along a cow, his bouncy, full-bellied laughter ricocheting off the light-yellow walls.

From a corner, standing with Deepak Bhakta, the Blake Fellow from Nepal who wouldn’t stop talking about his trekking business and his work-in-progress on racist Western trekkers, I kept tossing Kabumba contemptuous stares. I didn’t know why. Possibly because he made me look like an undesirable African, a fake. I was baffled by how much control he had over everyone. He could have cut his Maasai toga to pieces and auctioned each for a thousand dollars and they would have fallen over themselves to buy them without question.

When Deepak excused himself to use the bathroom, Kabumba broke free from his groupies and approached me, crossing the room in quick African strides. ‘My African brother,’ he greeted me, clasping my shoulders a little too tightly.

‘Hi,’ I greeted him back. ‘Nice toga.’

‘Thank you. My Kenyan friend gave it to me in Nairobi. The Maasai call them shukas,’ he corrected me.

‘Of course,’ I responded, shrinking, self-consciously plunging both hands into my tired, un-African chino pants.

‘Funny when Africans call them togas,’ he continued, standing next to me, a little too close, keeping an eye on his admirers around the room.

Professor Kirkpatrick was standing a few yards to our left, his back to us, chatting away with Claudia González, the playwright from Mexico, whose reworking of Brecht’s In the Jungle of Cities was already making the rounds of small theatres in New York.

Sara Chakraborty, in full Indian regalia, was holding a wine glass in one hand and gesticulating with the other, and I picked out fragments of something about ‘growing up in Surrey as the grandchild of Afro-Asian immigrants’.

‘I’m not saying you’re not African,’ said Kabumba the Ugandan, ‘just funny how we post-colonials are wired to see things through a Western lens.’

The word ‘post-colonial’ rang a sinister note coming from him, especially since I was already having an eerie feeling that the five of us – Sara, Deepak, Claudia, Kabumba and myself – were selected because we were ‘post-colonial’ writers whose worlds were interesting enough to jazz up the ‘conversation’ – another word that I was beginning to dread for what it conjured: a room full of intellectuals deconstructing and reconstructing one thing or the other.

‘Funny how that happens,’ I said to Kabumba.

‘So, how did you hear about this programme?’ he asked. ‘You Nigerians are everywhere. Always a Nigerian at this or that conference.’

I ignored his joke and tightened my jaw for a second before answering, ‘A friend told me about it. And you, how did you hear about it?’

‘Oh, I got an email from NAPA.’

‘Napa?’ I asked, irritated.

‘You’ve never heard of NAPA?’

Now he was getting on my nerves. I ignored his question.

‘NAPA. Network of African Poets and Authors?’

‘Right. Of course. Nice.’

‘You should join NAPA,’ he admonished me, ‘great place to network and connect with opportunities.’ He carried on about the NAPA newsletter he edited for three years until he ‘won’ the Blake Fellowship.

I ignored his remark and tried to change the subject.

‘You know, for a second I thought you were talking about Napa, you know, in California?’

He made a sound, drew closer, and in a conspiratorial voice said, ‘Funny, we are the only BAMEs here.’

‘BAM?’ I asked, trying hard to conceal my ignorance.

‘BAME,’ he said again, pronouncing it the way I heard it.

I racked my brain to get his drift. He rescued me.

‘They call it POC here, you know, People of Colour. But elsewhere, especially in the UK, it’s BAME. Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic.’

‘So that includes Sara, Deepa and Claudia?’

He ignored my question.

Fragments of Sara Chakraborty’s words floated about: ‘. . . this oppressive consciousness of the white middle classes, like their upper caste Indian counterparts . . . that is central to the present onslaught of right-wing pushbacks.’

I scanned the room for anything to latch onto and excuse myself.

I saw Perky, who I’d not met formally at this point. She was standing by herself, close to the door, playing with her name tag, which announced her as the Programmes Manager. She looked skinnier than her online photos suggested. I felt drawn to her, to the silence that surrounded her in that space where words were dropping like hailstones, like Sara Chakraborty’s ‘what we are witnessing on both sides of the Atlantic is symptomatic of a system that is consciously designed to subjugate and colonise’.

Kabumba carried on about his BAM, which he verbally footnoted with the inclusion of an ‘e’, BAME, repeating the soft letter as if to drive home a point I was not getting.

When he paused to drink from his glass, which seemed a little un-African in comparison to his attire and accessories, especially the stick, I summoned the courage to launch a subtle attack. ‘BAME in the UK, eh? Interesting, have you travelled there?’

Kabumba didn’t get my tone. He surveyed the room and began saying something about the William Blake programme, how happy he was to be back in Boston – he’d visited a few years ago to attend a conference organised by the World Youth Alliance for Cultural Freedom and Socio-Political Inclusion. He told me how much he was looking forward to finishing his first novel, a cross-genre work on the lives of sex workers in some coastal town on Lake Victoria. He wondered if I’d read his collection of stories that had been published a few years ago as a ‘downloadable pdf’ by ‘a micro press in Zanzibar’, the ‘book’ that landed him the Blake Fellowship. It was his fourth writing fellowship, he declared, and I wanted to counter with a question: ‘Do you need that number of fellowships and residencies to finish a single novel?’ He had also attended workshops – or ‘wackshaps’, as he pronounced it – in Kampala, Mombasa and Pretoria. There had been one in Prague, too, led by some English novelist whose name didn’t ring a bell, where he ‘wackshapped’ the first four chapters of his novel. Interestingly, his first fellowship had been in Nigeria, in a small village outside Ibadan, where he fell in love with jollof rice and concluded that Nigerian jollof must be better than Ghanaian jollof. ‘What do you think of the whole Ghana versus Nigeria jollof matter?’ he asked. I said I couldn’t care less about what cosmopolitan Africans cooked up to debate among themselves on Twitter. The word ‘cosmopolitan’ set him off on another tangent; he wondered what my thoughts were on Afropolitanism. I said I had none.

At this point I knew my hunch was right: the guy had too much energy.

Deepak was back and had cornered a freckled adjunct. I wished he would come and rescue me from Kabumba, who, as if reading my mind, asked, ‘What do you think about that Asian guy from Nepal?’

‘Asian guy?’ I asked, stressing the Asian. ‘I’ve just met him,’ I added and went no further.

To my relief, Deepak and the freckled adjunct came over and joined us. And in that instant, as if the universe had decided to favour me, Professor Kirkpatrick, in high spirits, came towards us and, a little too loudly, addressed Kabumba: ‘Hey K’boombah, may I steal you for a minute?’ He tapped the beaming Maasai impersonator on the shoulder, and they both walked towards a grey-haired woman in glasses standing alone beside the spread of cheese and grapes and cured meat, balancing some olives on a paper plate. She was, as Deepak’s new companion shared, a professor of anthropology with a focus on the mating behaviours of ‘indigenous’ societies in Africa, and she had recently received the Krank Prize for her work on the San people near the Okavango River.

Sara Chakraborty’s voice floated in again, something that included her ‘Oxford experience’ and ‘the lingering legacies of empire’ and ‘the Anglo-American flirtation with imperial amnesia’ that her last collection of essays ‘confronted’. From a corner of my eye I saw the shape and majestic sweep of her royal rust saree with its gold embroidery. Her listener, who I later learned was a French-Canadian ethnomusicologist and associate professor with experience of working in the Congo, seemed engrossed in whatever she was saying, his eyes glued to her face.

‘So, what are you working on?’ asked the freckled adjunct, who introduced herself as Chloe. She who would later become a recurring subject each time I met Deepak for coffee at Café Lucy – ‘Chloe and I went to see her family in Vermont’, ‘Chloe and I are planning an interdisciplinary project together’ – and soon enough Deepak would inch towards his ultimate intention, to propose to the freckled adjunct who he saw – and he didn’t hide this fact from me – as his ticket to becoming an ‘immigrant writer’ in America. An honest plan, in my opinion.

I responded to Chloe by repeating the question, ‘What am I working on?’ – a tactic I usually employed to buy time while formulating a believable answer.

Deepak jumped in and began to share his big plans to work on a documentary, and I was glad he did. I kept casting glances in Perky’s direction. I saw how uneasy she was. At one point our eyes met. She smiled and looked away.

As Deepak carried on, I found myself studying Chloe’s face, catching the spread and pattern of freckles on her right cheek. The freckles were reminding me of someone else, a certain white stripper who was flown in from somewhere to open a high-end club in Port Jumbo.

It was Martin, my boss at the Port Jumbo Post Office, married with four kids, who took me to see this stripper. He’d asked the day before, standing behind me at the till, if I’d been to a strip club before. I answered, ‘No, I haven’t.’ He said, ‘We must change that, Frank, and we must do so in a big way. You know, a new club is opening up in town, a fancy one, not those smelly ones with smelly bitches from the villages. This one will showcase classy chicks, university babes, and guess what? At the opening on Saturday, an American girl will be up there.’ The excitement in his voice was palpable. A customer came in to send a parcel to Finland (or was it Iceland?) and Martin returned to his office, only to emerge when the customer was gone and say, ‘Frank, there’s a picture of the white girl on their website, see, see.’ He handed me his smartphone and there she was, red hair, those Chloe-like freckles on both cheeks, topless, in a black thong, on the floor of a stage, her slim legs stretched apart. ‘She will be here in the flesh,’ Martin announced.

When I turned to hand him his phone, I saw that my boss, a father of four and a deacon at the Redeeming Light Global Church of Jesus Christ our Benefactor, the church to which he’d invited me with equal enthusiasm, had a slight bulge on the left side of his fly.

What had he been doing back in his office? Exciting himself over the freckled American stripper? Thank God we were alone there. ‘You should come, Frank. You know what, I’ll call the owner and save us two tickets.’

I listlessly accepted his invitation, but afterwards I wondered why he took an interest in me, why he made no effort to conceal his vices and split life from me, why he believed I would keep his secrets. And so we went to the Prime Gentlemen’s Club, which oddly sat on the same block as a private elementary school for rich kids, and, true to what Martin said, the stripper was white, but since she didn’t address the audience, there was no way to verify her nationality. She could as easily have been Canadian, German, white South African or white Kenyan.

The place was packed, but Martin had managed to secure a table up front, just close enough to see the stripper’s young face, to see the constellation of freckles appearing each time the club lights swept across her body.

I would occasionally look around, away from her, and take stock of the entire space, men with thirsty eyes, thrilled by the exoticism of the Chloe-like stripper, presumed American without evidence.

Just before midnight I said I was leaving, that I had to see a friend in the morning, which was a lie; I was simply tired by the cheer and rowdiness of middle-class Nigerian men.

To Chloe’s question, which she’d got around to asking again – ‘So, what are you working on?’ – I wanted to lie and say I was working on a novel about an English stripper who had a short career in Nigeria, in the coastal town of Port Jumbo. And to make it sound more interesting, I thought of adding a historical twist, to situate it in the past, that it was in fact a real account that took place in the early sixties, just after Nigeria gained its independence from Great Britain, and that the stripper turned out to be a spy in the service of Her Majesty’s Government, working to strip secrets from wealthy, cosmopolitan Nigerians with links to the new political class. But instead, and because the information was already public on the programme website, I shared my proposed project. ‘I’m working on a historical novel set in America and Sierra Leone in the mid to late 1800s,’ I said and avoided the meta-commentary on how it would ‘engage but also undo the global dimensions of violent histories’.

The idea intrigued her. She said, ‘Really? That sounds very exciting. What is it about?’

‘Oh, it’s about George Thompson, the missionary and abolitionist who sailed to Kaw Mendi, in what is now Sierra Leone, in 1848.’

‘How fascinating,’ she said, her large eyes widening as she inched closer, causing Deepak a pinch of distress.

I feigned the kind of modesty expected of a serious writer, and said, ‘Well, it’s still an idea in progress,’ and was about to add another thought when Claudia González joined us, with a bespectacled and chubby-cheeked lecturer, about our age but balding, in a grey crewneck sweater choking his skinny black tie, a Philip Larkin lookalike.

Carrying on a conversation he was having with Claudia, the Larkin lookalike said, ‘Always a diverse group,’ nodding in agreement with his own observation, perhaps expecting some multicultural input from the rest of us, the thought of which exhausted me.

I excused myself and walked towards Kabumba and the woman who studied the sexual appetites of primitive Africans, passed them, picked up a paper plate, considered the grapes and olives, lost interest altogether, and walked outside for fresh air.

In the growing darkness outside, I took deep breaths and wondered if it was best to head home. A group of students – so young – passed by. ‘I’ll send you the list,’ said a male voice behind me, ‘or you can just look it up online, Top Fifty Books by Women of Colour.’ It was the Larkin lookalike coming out the door with Claudia González. I hurried away from them.

Approaching the Humanities Hall, or St Pierre’s House, on my way to Comstock Place, I replayed my little conversation with Chloe. I was glad the conversation had ended the way it did, but also wished I had carried on and mentioned the context from which the Thompson story arose, to gauge her response. I could have said, ‘I grew up overhearing my Sierra Leonean mother talking about one of her ancestors who was taught by George Thompson himself,’ and then watched how Chloe reacted, and in the process measured my own ability to handle how people responded to such information.

According to my mother, that ancestor was a boy when Thompson landed in West Africa in 1848. The boy and his parents had arrived eight years before Thompson, twenty years after the first ship carrying freed slaves left New York for Sierra Leone.

The first time I looked up Thompson on the Internet, I saw that he had written extensively about his experience. One title stood out: Thompson in Africa, or an Account of the Missionary Labors, Sufferings, Travels, Observations, & C. of George Thompson, in West Africa, at the Mendi Mission (1852). There was another book, an earlier one, covering part of his life before the journey to West Africa, about his five-year imprisonment in Missouri for attempting to rescue slaves: Prison Life and Reflections; or a Narrative of the Arrest, Trial, Conviction, Imprisonment, Treatment, Observations, Reflections, and Deliverance of Work, Burr, and Thompson, Who Suffered an Unjust and Cruel Imprisonment in Missouri Penitentiary, for Attempting to Aid Some Slaves to Liberty (1851).

I downloaded both books and read them without much interest until I found myself racking my brains for what to include in my William Blake application. I could propose a project based on Thompson’s life, I thought. I had a feeling the committee would jump on the idea, considering how transatlantic it was and how personal.

Looking up Thompson’s life for the second time, I came across a paper by one J. Yannielli, a historian at Yale, ‘George Thompson among the Africans: Empathy, Authority, and Insanity in the Age of Abolition’, and I was struck by a small fact I’d missed earlier. Thompson, according to Yannielli, was ‘shocked to find a large group of schoolchildren participating in homosexual activities’. A group of gay boys in nineteenth-century West Africa. I pictured the American missionary, who had given up everything to bring salvation to that darkest part of the world, boiling over after this discovery.

But it was not the gay boys who tipped his sanity, nor was it the harsh weather or the evil mosquitoes that cracked his mind. It was the ‘crime’ of fornication by a pregnant woman that did the trick, causing Thompson to deal the savage fornicator fifty lashes, to the consternation of everyone, including fellow missionaries and proponents of corporal punishment. ‘I feel conscious of a growing roughness,’ Thompson wrote in his journal, ‘of manner and spirit, arising out of my circumstances.’

A Growing Roughness. The title I gave the novel I proposed to write at William Blake, for which the selection committee enthusiastically awarded me a generous fellowship.

Passing St Pierre’s House, Comstock Place in view, I tried to reimagine the shape of this non-existent novel, something different from how I’d proposed to write it. The idea of starting at the harbour in New York was appealing. I pictured my three-year-old ancestor and his parents waiting to board the ship, waiting with hundreds of other African Americans, freed slaves at the threshold of a world they knew and the one across the sea from which they’d been alienated for centuries; standing there at the lips of the vast ocean that bore their ancestors and that would now bear them back. I tried to imagine what crossed their minds, what shades of hope, what depths of fear. The world behind them was violent and cruel, but also familiar; the world ahead, although perceived as ‘home’, was unfamiliar and inconceivable. They were people of the faith, who’d found refuge in the Gospels, and in their hearts it was this faith that would guide them across the sea, lead them through the perils of settling down in West Africa, through new encounters with ‘animists and cannibals’, as one returnee wrote in a letter back to America. An Ever-Growing Roughness. The idea was now so strong I felt I needed to put down a line or two before entering Comstock Place.

I sat on the same bench I saw on my first day, and was about to start typing on my phone when I felt a presence behind me. I turned and saw Perky grinning as though her arrival was expected. She had undone her jet black hair, which now rested on her shoulder.

For no particular reason I looked around to make sure there wasn’t anyone from the party nearby. The campus street lamps were on, but it was dark enough in various corners that someone could be hiding and watching.

I wasn’t sure why her presence raised my paranoia. Student–faculty ‘relations’, as I read on a campus blog, were a ‘no-no’. Perky and I weren’t in either category but still I feared I might be breaking some code by just being out alone with her while an event was going on. My worries diminished when she said something about ‘the phoneys back there’ and how she ‘couldn’t stand’ such events, which was ironic because she had organised it.

I was relieved to know that I wasn’t the only one who couldn’t stand them. I wasn’t sure who the phoneys were for her – maybe the dean and faculty, all of whom seemed to gorge on every word and action of the ‘post-colonial’ fellows, worshipping them like gods from another world, the Old World of which America was its future. It was nonetheless refreshing to know she was not on their side like Sara’s listener, who I saw flushing with excitement, maybe desire, when Sara said something about ‘the politics and long histories of spice’. You would think he was ready to saddle up a horse and race east on the Silk Road to fetch her rare spices from the Orient.

I’d also seen how Perky was standing by herself near the door as if to flee without warning, her hand clasped in front of her – a gesture that had drawn my eyes to her green skirt, which ended just at the kneecap, followed by pale legs, straight and slender, that planted themselves in black Oxfords.

Sitting next to me on the bench, my first close company since my arrival, her legs spoke to me. The green skirt, now drawn up, introduced more pale skin, which in the different lighting of the street lamps looked enriched. She didn’t bother asking why I left but declared how she knew I too was ‘uncomfortable back there’, how she ‘could feel the different energy coming from me’, how she saw how much I wanted to ‘liberate myself’ from ‘the suffocation back there’.

I was careful not to make categorical statements in reply.

I tried to formulate a response to the effect that I truly loathed Barongo Akello Kabumba and Sara Chakraborty, that I was dreading the weeks ahead, how their march of authenticity and resistance would make me look like an indifferent and self-absorbed bastard.

I held my thoughts since I didn’t know where her own dislike for that group came from.

Mine was partly because I didn’t understand the depth of their moral authority, the immutable certainty with which they said things about the world and people and identity and the ‘post-colonial world’ of which they were clearly the true voices. I’d heard more about that ‘post-colonial world’ in a few days than all the years I lived in it, breathed its air, smelled its filth, lost my virginity in one of its many dark underbellies, survived years of crushing depression in its hold, endured its psychosis in the fragmented lives of my parents and their bohemian friends who crossed European ideas with anything they could find in their local milieu. But that ‘post-colonial world’, which I apparently ‘embodied’, was nothing like the fully formed and footnoted gunfire sentences I heard from Sara Chakraborty, nothing like the costumed performances of the Ugandan writer. Mine was just another tired world of ordinary and complicated people trudging along, like anywhere else, mostly oblivious of life beyond their neighbourhood, full of pain or courting happiness, vile or honest.

Perky’s presence was refreshing because it was new and held the possibility of an exit towards a different picture of America. I believed this more strongly when she offered me a cigarette and lit it for me. And while I smoked that first stick in America she sketched a portrait of a life that reminded me of the books I’d read, bringing some warmth to my heart, lifting me from the depths of ‘post-colonial despair’ to a place where, for a second, it seemed like I was now entering my true idea of America.

As ‘a working-class chick from Ohio’ who grew up with a single ‘drug-addicted mother’ in a ‘trailer park’ she could ‘sniff bs from a mile away’.

It wasn’t the sniffing that I liked but the little biographical detail, the image it conjured of the mother sitting on a foldable chair outside her trailer, smoking a joint or whatever she was addicted to, her enormous breasts pouring out of her distended tank top, and little Perky in whatever space was designated for her in the trailer, playing with some Barbie doll or dreaming of a faraway land, of an escape from the backward flatness of her small town to San Francisco or New York.

A smile crossed my face when she mentioned her actual escape from her hometown at the age of seventeen, driving east to New York for college at Vassar, after which she lived for two years in the Catskills, in ‘a community of makers and seekers’ from all over, and it was there that she met her first husband, a black poet from Damascus, Virginia, who had fled an abusive family to ‘just live and thrive’ up north.

I pictured some kind of twenty-first century underground railroad where black folks were fleeing north or wherever to ‘live and thrive’.

When the ‘community’ disintegrated, after it came out that the ‘leader’ kept ‘crossing the boundaries’, she and the black poet moved to Amsterdam for a year, travelling around Europe. They separated in Prague, after an ‘incident’, and she came back to the States, where she applied and got the job at William Blake.

The job itself was disappointing when it did not ‘deliver what she needed to thrive’. But she knew this ‘year would be different when she read my email and looked me up’.

I pinched the cigarette butt harder than necessary.

A group of students walked past.

I tried to make sense of the gaps in her story, the omissions and vagueness.

When she said she had read my book, I not only tensed but also understood clearly why she was sharing her ‘journey’ with me. She saw similarities between some aspects of her life and that of my character, and she could also tell that I was ‘more daring and original’ than the other fellows.

I wasn’t sure about the originality but I was flattered all the same, and she compared my work to ‘something Salinger would have written if he was born and bred in Africa’.

I felt a rush of blood and a little warmth in my crotch. It was a new feeling, this positive response to a compliment from a reader of my work. Maybe it was the atmosphere, sitting on that bench in a dreamy spot on a quiet campus in America. Maybe a part of me was craving reassurance, some form of acceptance. I suddenly felt proud of my work, its universal appeal, its ability to gather the human condition far and near under its own relatable roof.

Out of curiosity, I asked how she got my book.

Apparently, Betty had donated her copy to the Harry Putnam Library and Perky had borrowed it soon after I sent her my initial inquiry. She had repeated those words, ‘initial inquiry’, which made me wonder if she still remembered the typo in my email, ‘the global dementias of violent hosieries’. My mood swung from where it was to a lower rung.

Involuntarily, I looked at Comstock Place, hoping to find an excuse to flee the scene.

She uncrossed her legs, as if to reorder my gaze.

She tugged the edges of her skirt.

She asked me, ‘How about we take this conversation elsewhere?’

She stood up and I found myself following her, my mind suspended between confidence and crushing self-doubt. I didn’t care to ask where we were going. There was an air of command and authority about her that magnetised me. And she seemed to know this about herself and her voice, because she did not wait for me to answer or look to see if I was comfortable following her. She simply led and I followed like a loyal dog. She had also, in that instant, transformed from the ‘sharing’ Perky to a more dominant figure who knew precisely what she wanted, and how and where she wanted it.

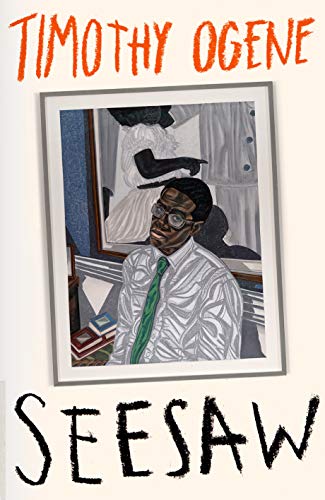

Image © amwell12

This is an excerpt from Seesaw by Timothy Ogene, published by Swift Press.