Losing the Game of Meaning on Social Media

Let’s just do the most recent one. There will be another by the time you’re reading this. There will probably be another one by the time I’ve finished writing it.

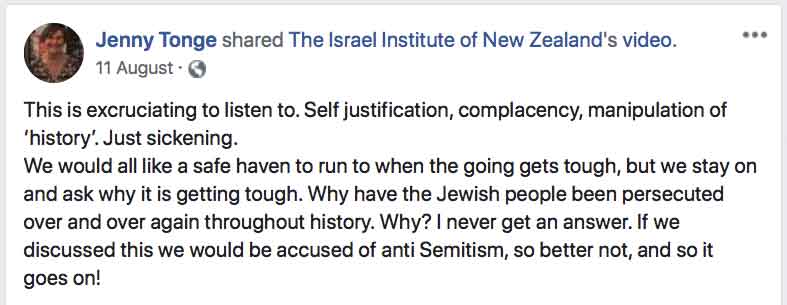

On 11 August 2018, in response to a video entitled ‘I Am a Zionist’, Baroness Jenny Tonge, a peer in the House of Lords, wrote this on her Facebook page:

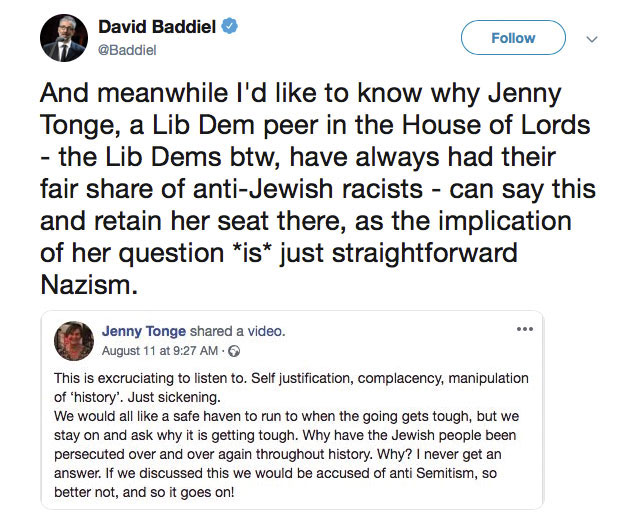

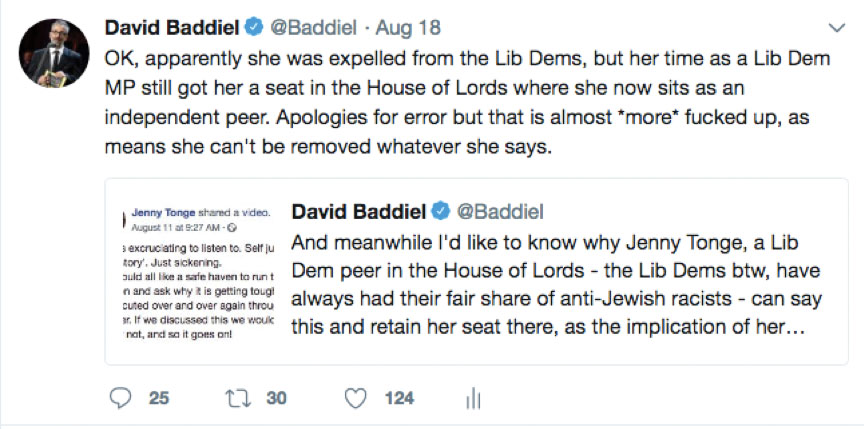

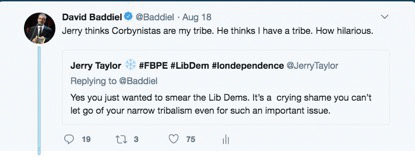

Derrida would also be down with the idea that the meaning of an utterance, as soon it’s out there and being refracted through other utterances, starts to slip and slide. He’d be overjoyed, for example, to discover that my post contained errors. Tonge, I was immediately told by various people, is no longer a Liberal Democrat. So I posted this:

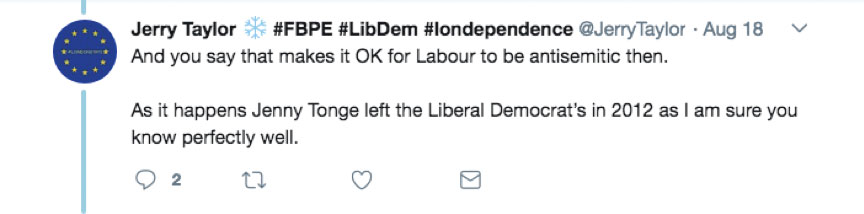

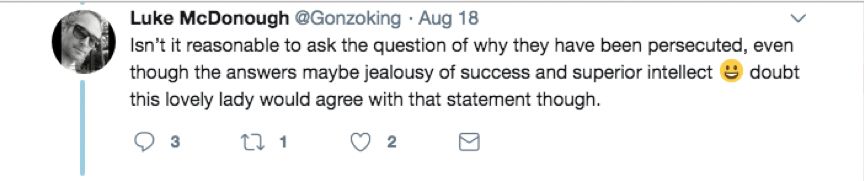

In fact, here is one such example:

By ‘it’, I mean the digression. The more eagle-eyed among you may have noticed that I’ve so far failed to talk about the issue at the centre of this piece: the implicit anti-Semitism within Tonge’s original post. That’s because I think all this backstory, all these addenda, help to understand the complexity of what you might call right and wrong in 2018. I tried to highlight a wrong in Tonge’s post. But then very quickly got drawn into a series of battles over a different, failed wrong, which distracted from the far greater wrong inherent in the not-any-more-Lib-Dem’s message. One possibility would be to ignore those diversions, but I find this difficult, I reflexively want to answer everyone who writes to me on Twitter. This is a bad urge, as disregarding about 90 per cent of what comes in in response to tweets, especially tweets on the subject of Jews, can definitely be a good option. However in this case, dealing with the digressions felt right. Because if someone is saying something deeply wrong, deeply untrue, then, in calling them out, it’s your responsibility to get everything right, to hold your utterance to a higher standard of truth.

So let’s try and do that. Tonge’s implication in her question about Jews – ‘Why have the Jewish people been persecuted over and over again throughout history. Why?’ – is that there must be some reason for this, and that the fault lies with the Jews. It’s what we now call victim-blaming, although that isn’t a term that, say, Adolf Hitler would have been familiar with when he claimed, in Mein Kampf, that the Jew ‘was only and always a parasite in the body of other peoples’. (To find this quote I went to a random chapter of Mein Kampf – available, of course, freely on the internet – and put ‘always’ into the search engine because the one thing I know about anti-Semitism is that the anti-Semite believes the Jew never changes, which is the reason they might have been persecuted throughout history.)

I knew in advance, because Twitter has conditioned me to second-guess people’s responses, what the challenges to my tweet about Tonge’s post would be. I knew some people would tell me that Tonge’s post – which has a silence at its heart – does not say that Jews are responsible for their own persecution. It simply puts forth a question about why:

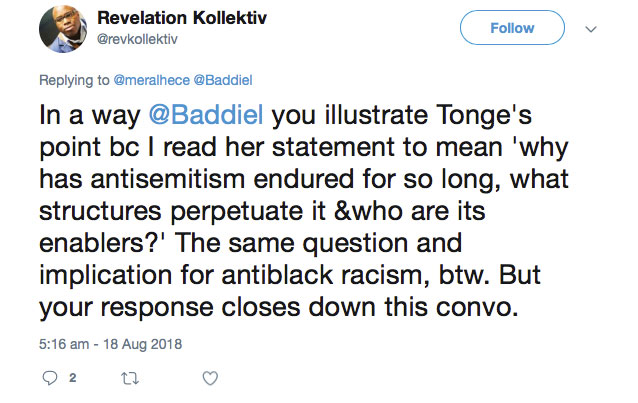

Another tweeter agreed that the reasons lie outside and are imposed on Jews, but didn’t necessarily assume that Tonge couldn’t have meant this:

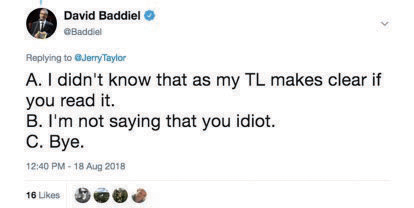

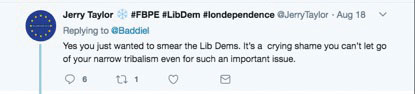

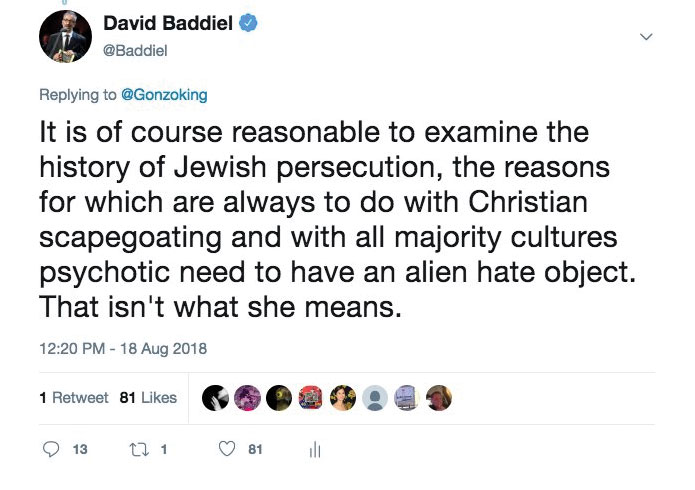

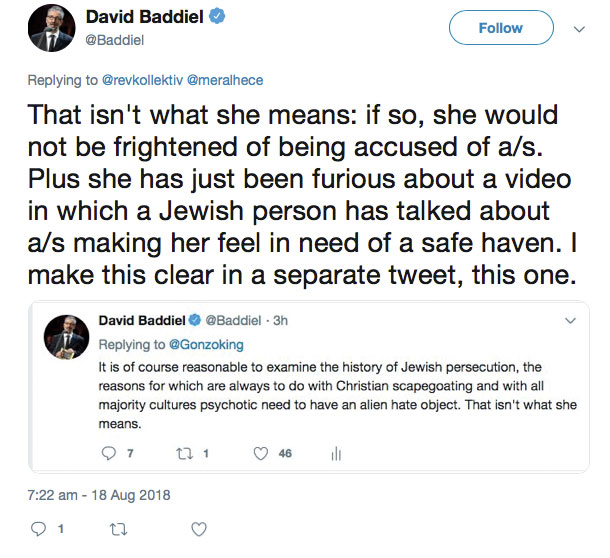

I replied, quote-tweeting my previous reply:

How do I know – to ask a rhetorical question – that Tonge’s question is rhetorical? That this answer she so desperately claims to want is in fact one she has absolutely at the ready?

Sign in to Granta.com.