The power of John Donne’s words nearly killed a man. It was the late spring of 1623, on the morning of Ascension Day, and Donne had finally secured for himself celebrity, fortune and a captive audience. He had been appointed the Dean of St Paul’s Cathedral two years before: he was fifty-one, slim and amply bearded, and his preaching was famous across the whole of London. His congregation – merchants, aristocrats, actors in elaborate ruffs, the whole sweep of the city – came to his sermons carrying paper and ink, wrote down his finest passages and took them home to dissect and relish, pontificate and argue over. He often wept in the pulpit, in joy and in sorrow, and his audience would weep with him. His words, they said, could ‘charm the soul’.

That morning he was not preaching in his own church, but fifteen minutes’ easy walk across London at Lincoln’s Inn, where a new chapel was being consecrated. Word went out: wherever he was, people came flocking, often in their thousands, to hear him speak. That morning, too many people flocked. ‘There was a great concourse of noblemen and gentlemen’, and in among ‘the extreme press and thronging’, as they pushed closer to hear his words, men in the crowd were shoved to the ground and trampled. ‘Two or three were endangered, and taken up dead for the time.’ There’s no record of Donne halting his sermon; so it’s likely that he kept going in his rich, authoritative voice as the bruised men were carried off and out of sight.

–

Just fifteen years before that, the same man finished a book and immediately put it away. He knew as he wrote it that it could be dangerous to him were it to be discovered. He was living in obscurity in Mitcham, in a cold house with thin walls and a noxious cellar that leaked ‘raw vapours’ to the rooms above, distracted by a handful of gamesome and clamouring children. It was a book written in illness and poverty, to be read by almost no one. The book was called Biathanatos; a text which has claim to being the first full-length treatise on suicide written in English. It laid out, with painstaking precision, how often its author dreamed of killing himself.

–

A decade or so before, the same man, then about twenty-three years old, sat for a portrait. The painting was of a man who knew about fashion; he wore a hat big enough to sail a cat in, a big lace collar, an exquisite moustache. He positioned the pommel of his sword to be just visible, an accessory more than a weapon. Around the edge of the canvas was painted in Latin, ‘O Lady, lighten our darkness’; a not-quite-blasphemous misquotation of Psalm 17, his prayer addressed not to God but to a lover. And his beauty deserved walk-on music, rock-and-roll lute: all architectural jawline and hooked eyebrows. Those eyebrows were the author of some of the most celebratory and most lavishly sexed poetry ever written in English, shared among an intimate and loyal group of hyper-educated friends:

License my roving hands, and let them go

Behind, before, above, between, below!

O my America! My new-found land!

My kingdom, safeliest when with one man manned!

Sometime religious outsider and social disaster, sometime celebrity preacher and establishment darling, John Donne was incapable of being just one thing. He reimagined and reinvented himself, over and over: he was a poet, lover, essayist, lawyer, pirate, recusant, preacher, satirist, politician, courtier, chaplain to the King, dean of the finest cathedral in London. It’s traditional to imagine two Donnes – Jack Donne, the youthful rake, and Dr Donne, the older, wiser priest, a split Donne himself imagined in a letter to a friend – but he was infinitely more various and unpredictable than that.

Donne loved the trans-prefix: it’s scattered everywhere across his writing – ‘transpose’, ‘translate’, ‘transport’, ‘transubstantiate’. In this Latin preposition – ‘across, to the other side of, over, beyond’ – he saw both the chaos and potential of us. We are, he believed, creatures born trans- formable. He knew of transformation into misery: ‘But O, self traitor, I do bring/The spider love, which transubstantiates all/And can convert manna to gall’ – but also the trans- formation achieved by beautiful women: ‘Us she informed, but transubstantiates you’.

And then there was the transformation of himself: from failure and penury, to recognition within his lifetime as one of the finest minds of his age; one whose work, if allowed under your skin, can offer joy so violent it kicks the metal out of your knees, and sorrow large enough to eat you. Because amid all Donne’s reinventions, there was a constant running through his life and work: he remained steadfast in his belief that we, humans, are at once a catastrophe and a miracle.

There are few writers of his time who faced greater horror. Donne’s family history was one of blood and fire; a great-uncle was arrested in an anti-Catholic raid and executed: another was locked inside the Tower of London, where as a small schoolboy Donne visited him, venturing fearfully in among the men convicted to death. As a student, a young priest whom his brother had tried to shelter was captured, hanged, drawn and quartered. His brother was taken by the priest hunters at the same time, tortured and locked in a plague-ridden jail. At sea, Donne watched in horror and fascination as dozens of sailors burned to death. He married a young woman, Anne More, clandestine and hurried by love, and as a result found himself thrown in prison, spending dismayed ice-cold winter months first in a disease-ridden cell and then under house arrest. Once married, they were often poor, and at the mercy of richer friends and relations; he knew what it was to be jealous and thwarted and bitter. He was racked, over and over again, by life-threatening illnesses, with dozens of bouts of fever, aching throat, vomiting; at least three times it was believed he was dying. He lost, over the course of his life, six children: Francis at seven, Lucy at nineteen, Mary at three, an unnamed stillborn baby, Nicholas as an infant, another stillborn child. He lost Anne, at the age of thirty-three, her body destroyed by bearing twelve children. He thought often of sin, and miserable failure, and suicide. He believed us unique in our capacity to ruin ourselves: ‘Nothing but man, of all envenomed things,/Doth work upon itself with inborn sting’. He was a man who walked so often in darkness that it became for him a daily commute.

But there are also few writers of his time who insisted so doggedly and determinedly on awe. His poetry is wildly delighted and captivated by the body – though broken, though doomed to decay – and by the ways in which thinking fast and hard were a sensual joy akin to sex. He kicked aside the Petrarchan traditions of idealised, sanitised desire: he joyfully brought the body to collide with the soul. He wrote: ‘one might almost say her body thought.’ In his sermons, he reckoned us a disaster, but the most spectacular disaster that has ever been. As he got older he grew richer, harsher, sterner and drier, yet he still asserted: ‘it is too little to call Man a little world; except God, man is a diminutive to nothing. Man consists of more pieces, more parts, than the world doth, nay, than the world is.’ He believed our minds could be forged into citadels against the world’s chaos: he wrote in a verse letter, ‘be thine own palace, or the world’s thy jail.’ Tap a human, he believed, and they ring with the sound of infinity.

Joy and squalor: both Donne’s life and work tell that it is fundamentally impossible to have one without taking up the other. You could try, but you would be so coated in the unacknowledged fear of being forced to look, that what purchase could you get on the world? Donne saw, analysed, lived alongside, even saluted corruption and death. He was often hopeless, often despairing, and yet still he insisted at the very end: it is an astonishment to be alive, and it behoves you to be astonished.

–

How much of Donne remains to us? Those who love Donne have no choice but to relish the challenge of piecing him together from a patchwork of what we do and do not know. He is there in his work, always; but there are moments in his life where we must work out from fragments and clues what it was that he was doing: there is a long gap in his childhood, another after university, more after his marriage, and in his later years he flickers in and out of sight. Time eats your paperwork, and it has eaten some of his. We have, for instance, not yet discovered any diaries, no books of household notes or accounts. There are no manuscript drafts of poems – we have only one English poem in his own handwriting – and so no evidence of him at work, building the verse from false starts and scratches. He burned all his friends’ letters to him after they died; a letter was, for him, akin to an extension of the living person, and should not exist without its parent – so we have no gossipy to-and-fros in the letter archive.

But what remains is a miracle; because a colossal amount of Donne’s work has been rescued from time’s hunger, remarkable in the period for its variety and sweep.

There are two long prose treatises on religious questions, one of which – an attack on the Jesuits called Ignatius His Conclave – is racy and explosive and delicious, and the other of which – an argument that Catholics must take the Oath of Allegiance to the King, called Pseudo-Martyr – is so dense it would be swifter to eat it than to read it. There are thirty-one pieces of half satirical, half serious prose writing called the Problems and Paradoxes: essays with stings in them, and the Essays in Divinity, which are hyper-learned disquisitions on various books of the Bible. There is Biathanatos, his treatise on suicide, an interrogation of sin and conscience. There are the Devotions upon Emergent Occasions, a collection of twenty-three meditations on humanity, written at breakneck speed during a near-fatal illness in the very teeth of what Donne believed was going to be his death. (Having published them within weeks of writing them, he went on to survive another eight years.) There are 160 sermons, dating from 1615 to 1631 – six of which were published during his lifetime, the rest collected by his son into three great luxurious folios after his death.

There are 230 letters, to his friends, patrons and employers, the majority of which were also collected and published posthumously by his son, John Donne junior. John junior had a bad habit, when editing the letters, of removing all dates and changing the names of the addressees to make his father’s early acquaintance seem more high-flying and high-society, so dating and attributing them is an ongoing and gargantuan task. Anyone turning to the prose letters seeking disquisitions on politics or news of his love affairs would be disappointed; Donne lived under a state which both censored and spied on its citizens, and his letters are largely – though not solely – practicalities. Will you come for dinner? I am ill. Might you give me money? Can you find me work? (Or, more accurately, because a significant portion of the letters are outrageous pieces of flattery: you are so ravishingly exquisite, can you find me work?)

And there are the poems: about two hundred of them, totalling just over 9,100 lines. In among those lines are epithalamia – poems written to salute a marriage – and obsequies – poems written to mourn a death. There are satires, religious verse, and about forty verse letters, a tradition he loved; poems of anything from twelve to 130 lines, carrying news, musings on virtue and God, and declarations of how richly he treasures the friend to whom he is writing. The idea of writing letters in verse wasn’t his own – Petrarch did it, and the tradition dates all the way back to Ovid, whose Heroides are imagined verse letters by the wronged heroines of Roman and Greek myths – but Donne seems to have used the form more than any other poet of his lifetime. There was something in the way a verse letter could elevate the details of the day-to-day and render it sharp-edged and memorable that he cherished. It appealed to the part of him that wanted his own brand of intense precision to suffuse everything he touched.

And then there is the work Donne is most famous for; the love poetry and the erotic verse. To call anyone the ‘best’ of anything is a brittle kind of game – but if you wanted to play it, Donne is the greatest writer of desire in the English language. He wrote about sex in a way that nobody ever has, before or since: he wrote sex as the great insistence on life, the salute, the bodily semaphore for the human living infinite. The word most used across his poetry, apart from ‘and’ and ‘the’, is ‘love’.

This body of surviving work is enough, taken together, to make the case that Donne was one of the finest writers in English: that he belongs up alongside Shakespeare, and that to let him slowly fall out of the common consciousness would be as foolish as discarding a kidney or a lung. The work cuts through time to us: but his life also cannot be ignored – because the imagination that burns through his poetry was the same which attempted to manoeuvre through the snake pit of the Renaissance court. This book, then, hopes to do both: both to tell the story of his life, and to point to the places in his work where his words are at their most singular: where his words can be, for a modern reader, galvanic. His work still has the power to be transformative. This is both a biography of Donne and an act of evangelism.

–

You cannot claim a man is an alchemist and fail to lay out the gold. This, then, is an undated poem, probably written for Anne More, some time in his twenties, known as ‘Love’s Growth’ –

I scarce believe my love to be so pureAs I had thought it was,Because it doth endureVicissitude, and season, as the grass;Methinks I lied all winter, when I sworeMy love was infinite, if spring make’ it more.But if medicine, love, which cures all sorrowWith more, not only be no quintessence,But mixed of all stuffs paining soul or sense,And of the sun his working vigor borrow,Love’s not so pure, and abstract, as they useTo say, which have no mistress but their muse,But as all else, being elemented too,Love sometimes would contemplate, sometimes do.And yet no greater, but more eminent,Love by the spring is grown;As, in the firmament,Stars by the sun are not enlarged, but shown,Gentle love deeds, as blossoms on a bough,From love’s awakened root do bud out now.If, as water stirred more circles beProduced by one, love such additions take,Those, like so many spheres, but one heaven make,For they are all concentric unto thee;And though each spring do add to love new heat,As princes do in time of action getNew taxes, and remit them not in peace,No winter shall abate the spring’s increase.

Read the opening stanza and all the oxygen in a five-mile radius rushes to greet you. It’s a poem with gleeful tricks and puns in it. ‘But if this med’cine, love, which cures all sorrow/With more’ is a small, private gift for Anne More; no matter how many millions of other people have read it since, the poem was different for her. Donne baked time’s accumulation and love’s accumulation with it into the structure of the poem: twenty-four ten-syllable lines, plus four of six (equalling twenty-four): the hours in the day. Seven rhymes per stanza: the days in the week. Twenty-eight lines in the poem: the days in a lunar month, each day part of love’s growth.

Love, he writes, is a mixture of elemental things: ‘as all else being elemented too’ – and so ‘love sometimes would contemplate, sometimes do.’ Donne is more daring than he sounds: the thirteenth-century theologian Thomas Aquinas’s ideal was the ‘Mixed Life’, one of contemplation and action. Donne hijacks the Aquinian ideal for his own erotic purpose: the do is sex. It’s the same impulse as in another poem, ‘The Ecstasy’, where bodies must join as well as minds, ‘else a great prince in prison lies.’ True sex, he insists, is soul played out in flesh.

‘Love’s Growth’ hangs on the idea of apparently infinite love, made more – which, once you have read all that he wrote, is wholly unsurprising. John Donne was an infinity merchant; the word is everywhere in his work. More than infinity: super-infinity. A few years before his own death, Donne preached a funeral sermon for Magdalen Herbert, mother of the poet George Herbert, a woman who had been his patron and friend. Magdalen, he wrote, would ‘dwell bodily with that righteousness, in these new heavens and new earth, for ever and ever and ever, and infinite and super-infinite forevers’. In a different sermon, he wrote of how we would one day be with God in ‘an infinite, a super-infinite, an unimaginable space, millions of millions of unimaginable spaces in heaven’. He loved to coin formations with the super-prefix: super-edifications, super-exaltation, super-dying, super-universal, super-miraculous. It was part of his bid to invent a language that would reach beyond language, because infinite wasn’t enough: both in heaven, but also here and now on earth, Donne wanted to know something larger than infinity. It was absurd, grandiloquent, courageous, hungry.

That version of Donne – excessive, hungry, longing – is everywhere in the love poetry. Sometimes it was worn lightly: who has yet written about nudity with more glee, more jokes? In ‘To His Mistress Going to Bed’, written in his twenties, the speaker attempts to coax his lover out of her clothes:

Full nakedness! All joys are due to thee:

As souls unbodied, bodies unclothed must be

To taste whole joys.

The poem could be seen as one of domineering masculinity, except that at the end of it there’s a joke: only the man stands naked. ‘To teach thee, I am naked first; why then/ What need’st thou have more cov’ring than a man?’

Then there is the wilder, defiantly odd Donne, typified by the poem for which most people know him, ‘The Flea’. The speaker watches a flea crawl over the body of the woman he desires:

Mark but this flea, and mark in this

How little that which thou deny’st me is;

Me it sucked first, and now sucks thee,

And in this flea, our two bloods mingled be.

When the poem was first printed in 1633, the typographers used the ‘long s’, a letter that looks almost identical to an f, for the words ‘sucked’ and ‘suck’: which offers readers of the third line another, more extravagant rendering.

In ‘Love’s Progress’, he summons up the outlandish edge of sex. He describes a woman’s mouth:

There in a creek, where chosen pearls do swell,

The remora, her cleaving tongue doth dwell.

The remora is a sucking fish; it was supposed, according to Pliny the Elder, to have the ability to haul ships to a stop in the ocean. Not many women dream of having their tongues compared to semi-mythical sea creatures – but, as with his flea, it’s his way of embodying the strangenesses of human fleshy desire. He allows himself to end on a major chord, a switch to bawdy lusting:

Rich Nature in women wisely made

Two purses, and their mouths aversely laid:

They, then, which to the lower tribute owe,

That way which that exchequer looks must go;

He which doth not, his error is as great

As who by clyster gives the stomach meat.

Donne seems to deserve the questionable recognition of being the first to so use ‘purse’ for female genitalia. The ‘exchequer’ implies that those who travel down the body must pay a tax: and ejaculate is the fitting tribute. (Men were believed to need a huge amount of blood to form sperm within the body: a ratio of 40:1.) A ‘clyster’ is an enema tube which was used to carry nutrients to the body via the rectum. The argument – that those who don’t consummate love are as mad and upside-down as those who try to nourish the body via the anus – has teeming desire in it, but very much resists the tradition of Petrarchan flowers. It refuses to be pretty, because sex is not and because Donne does not, in his love poetry, insist on sweetness: he does not play the ‘my lady is a perfect dove’ game beloved by those who came before him. What good is perfection to humans? It’s a dead thing. The urgent, the bold, the witty, the sharp: all better than perfection.

There is the meat and madness of sex in his work – but, more: Donne’s poetry believed in finding eternity through the human body of one other person. It is for him akin to sacrament. Sacramentum is the translation in the Latin Bible for the Greek word for mystery: and Donne knew it when he wrote, ‘We die and rise the same, and prove/Mysterious by this love.’ He knew awe: ‘All measure, and all language, I should pass/Should I tell what a miracle she was.’ And in ‘The Ecstasy’, love is both a mystery and its solution. He needed to invent a word, ‘unperplex’, to explain:

‘This ecstasy doth unperplex,’

We said, ‘and tell us what we love . . .’But as all several souls contain

Mixture of things, they know not what,

Love these mixed souls doth mix again,

And makes both one, each this and that.

‘Each this and that’: his work suggests that we might voyage beyond the blunt realities of male and female. In ‘The Undertaking’, probably written around the time he met Anne, the body can take you to a grand merging:

If, as I have, you also do Virtue attired in woman see,

And dare love that, and say so too,

And forget the ‘he’ and ‘she’ . . .

His poetry sliced through the gender binary and left it gasping on the floor. It’s in ‘The Relic’, too: ‘diff’rence of sex no more we knew/Than our guardian angels do’ – for angels were believed to have no need of gender. He offered the possibility of sex as transformation: and we are more tempted to believe him when he says it, because he is the same man who acknowledges, elsewhere, feverishness, disappointment and spite in love. He is sharp, funny, mean, flippant and deadly serious. He shows us that poetry is the thing – perhaps the only thing – that can hold love in words long enough to look honestly at it. Look: love.

–

He took his galvanising imagination and brought it to bear on everything he wrote: his sermons, his meditations, his religious verse. In the twenty-first century, Donne’s imagination offers us a form of body armour. His work is protection against the slipshod and the half-baked, against anti-intellectualism, against those who try to sell you their money-ridden vision of sex and love. He is protection against those who would tell you to narrow yourself, to follow fashion in your mode of thought. It’s not that he was a rebel: it is that he was a pure original. They do us a service, the true uncompromising originals: they show us what is possible.

To tell the story of Donne’s life is to ask a question: how did he, possessed of a strange and labyrinthical mind, navigate the corresponding social and political labyrinths of Renaissance England? What did his imagination look like when he was young, and how was it battered and burnished as he grew older? Did it protect him from sorrow and fury and resentment? (To spoil the suspense: it did not.) Did it allow him to write out the human problem in a way that we, following on four hundred years later, can still find urgent truth in? This book argues that it did. ‘Dark texts’, he wrote to a friend, ‘need notes’ – and it is possible to see his whole body of work as offering us a note on ourselves. This book aims to lay out that note as clearly as possible: how John Donne saw us with such clarity, and how he set down what he knew with such precision and flair that we can seize hold of it, and carry it with us. He knew about dread, and it is therefore that we can trust him when he tells us of its opposite, of ravishments and of love.

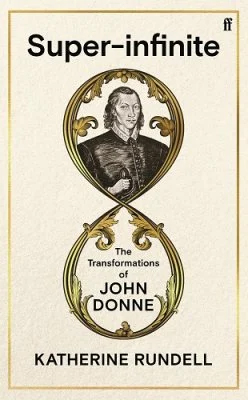

Image © JR P