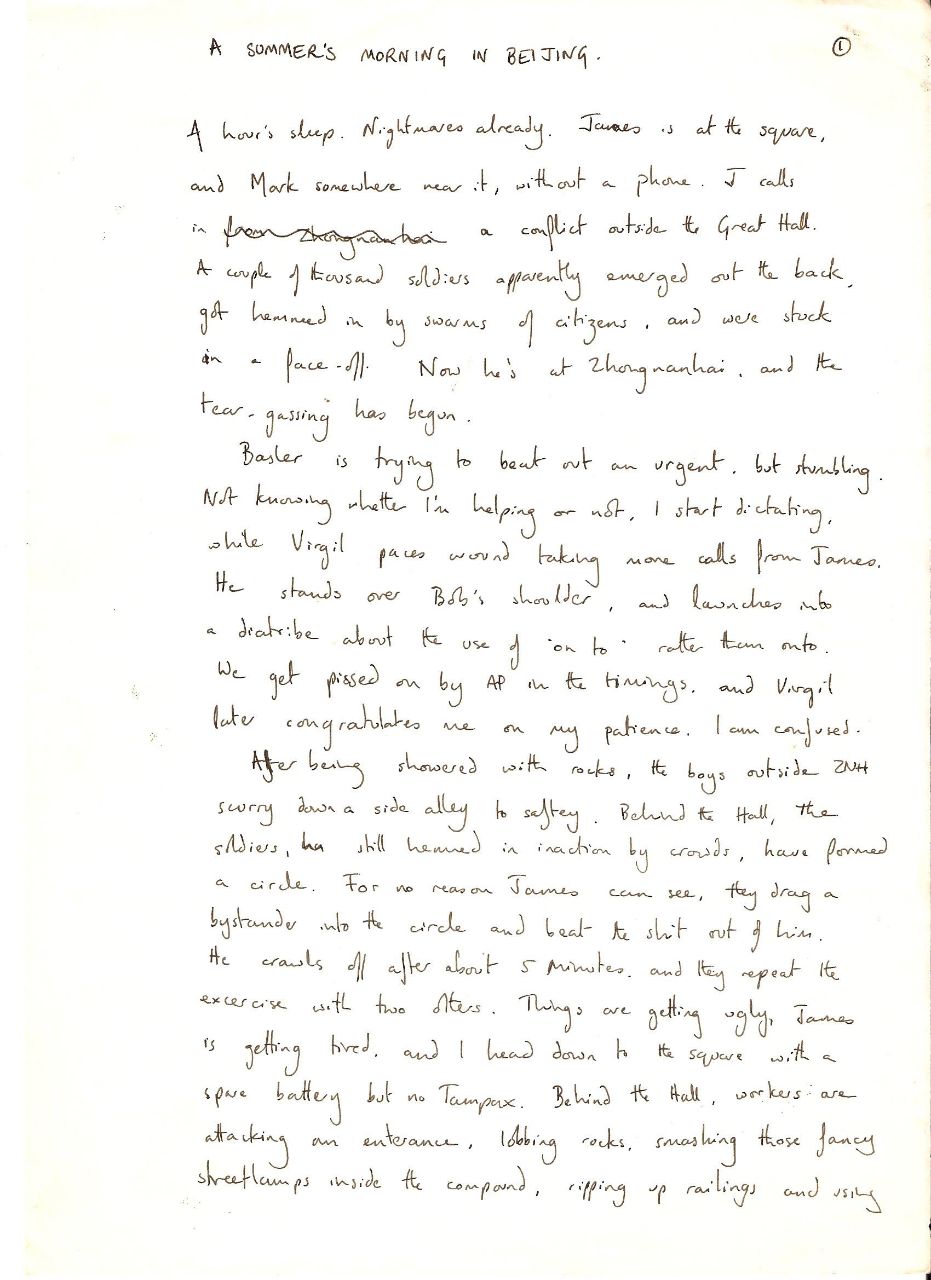

In May 1989, Elizabeth Pisani – then a young reporter for the Reuters news agency – was sent to Beijing to cover the protests taking place in Tiananmen Square, which culminated in the massacre during the night of the following 3 June. In ‘Chinese Whispers’, published in Granta 105, she explores her memories of the violence and her own role as a witness and journalist. Below is her account of what she witnessed in Tiananmen Square, written in 1989, shortly after she left Beijing. The original manuscript of her account can be found below this article.

An hour’s sleep. Nightmares already. James is at the square and Mark somewhere near it, without a phone. J calls in a conflict outside the Great Hall. A couple of thousand soldiers apparently emerged out the back, got hemmed in by swarms of citizens, and were stuck in a face-off. Now he’s at Zhongnanhai, and the tear-gassing has begun.

Basler is trying to beat out an urgent, but stumbling. Not knowing whether I’m helping or not, I start dictating, while Virgil paces around taking more calls from James. He stands over Bob’s shoulder, and launches into a diatribe about the use of ‘on to’ rather than onto. We get pissed on by AP in the timings and Birgil later congratulates me on my patience. I am confused.

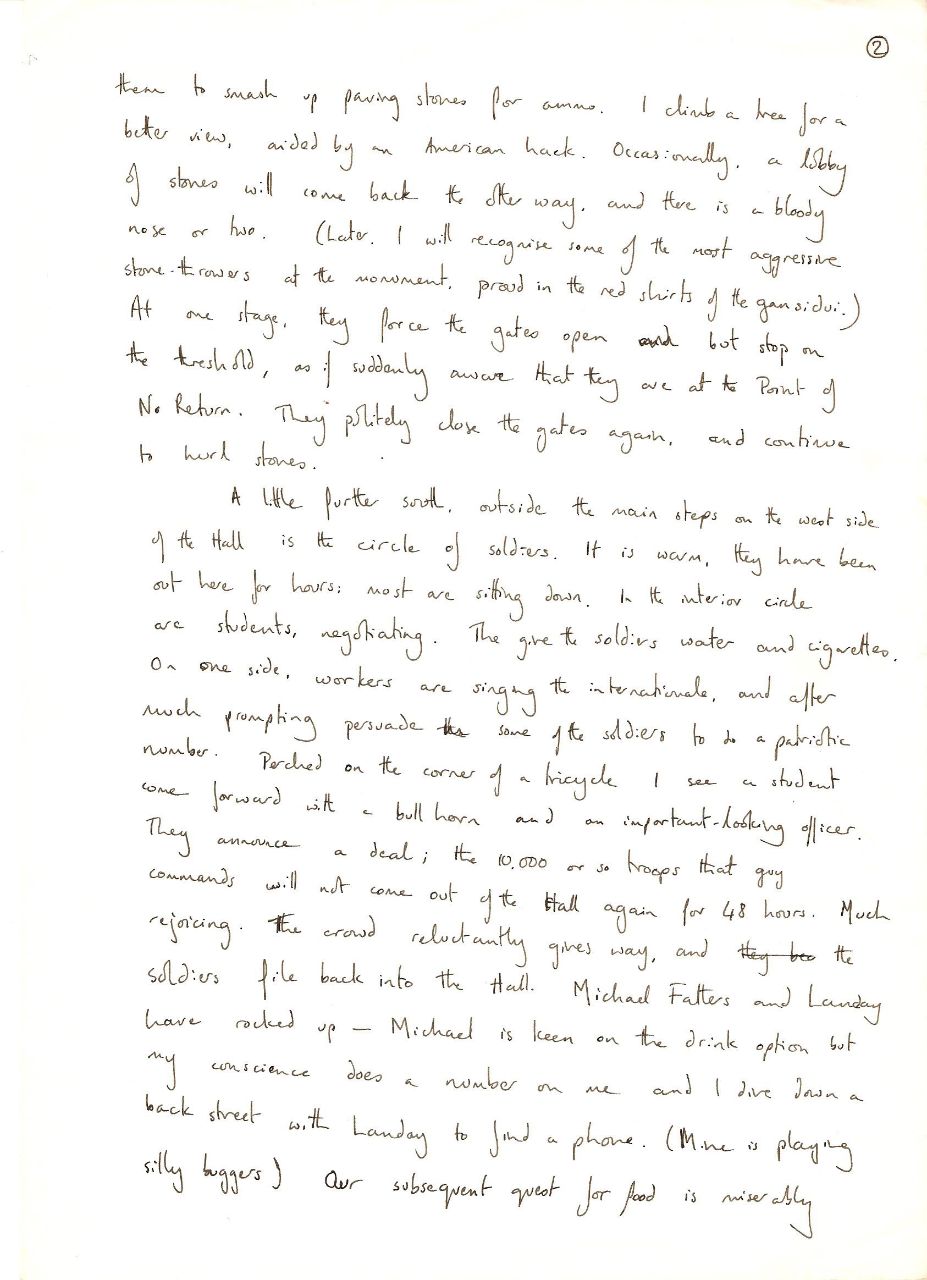

After being showered with rocks, the boys outside ZNH scurry down a side alley to safety. Behind the Hall, the soldiers, still hemmed in inaction by crowds, have formed a circle. For no reason James can see, they drag a bystander into the circle and beat the shit out of him. He crawls off after about five minutes, and they repeat the exercise with two others. Things are getting ugly, James is getting tired, and I head down to the square with a spare battery but no Tampax. Behind the Hall, workers are attacking an entrance, lobbing rocks, smashing those fancy streetlamps inside the compound, ripping up railings and using them to smash up paving stones for ammo. I climb a tree for a better view, aided by an American hack. Occassionally, a lobby of stones will come back the other way, and there is a bloody nose or two. (Later, I will recognise some of the most aggressive stone-throwers at the monument, proud in red shirts of the gansidui.) At one stage, they force the gates open but stop on the threshold, as if suddenly aware that they are at the Point of No Return. They politely close the gates again, and continue to hurl stones.

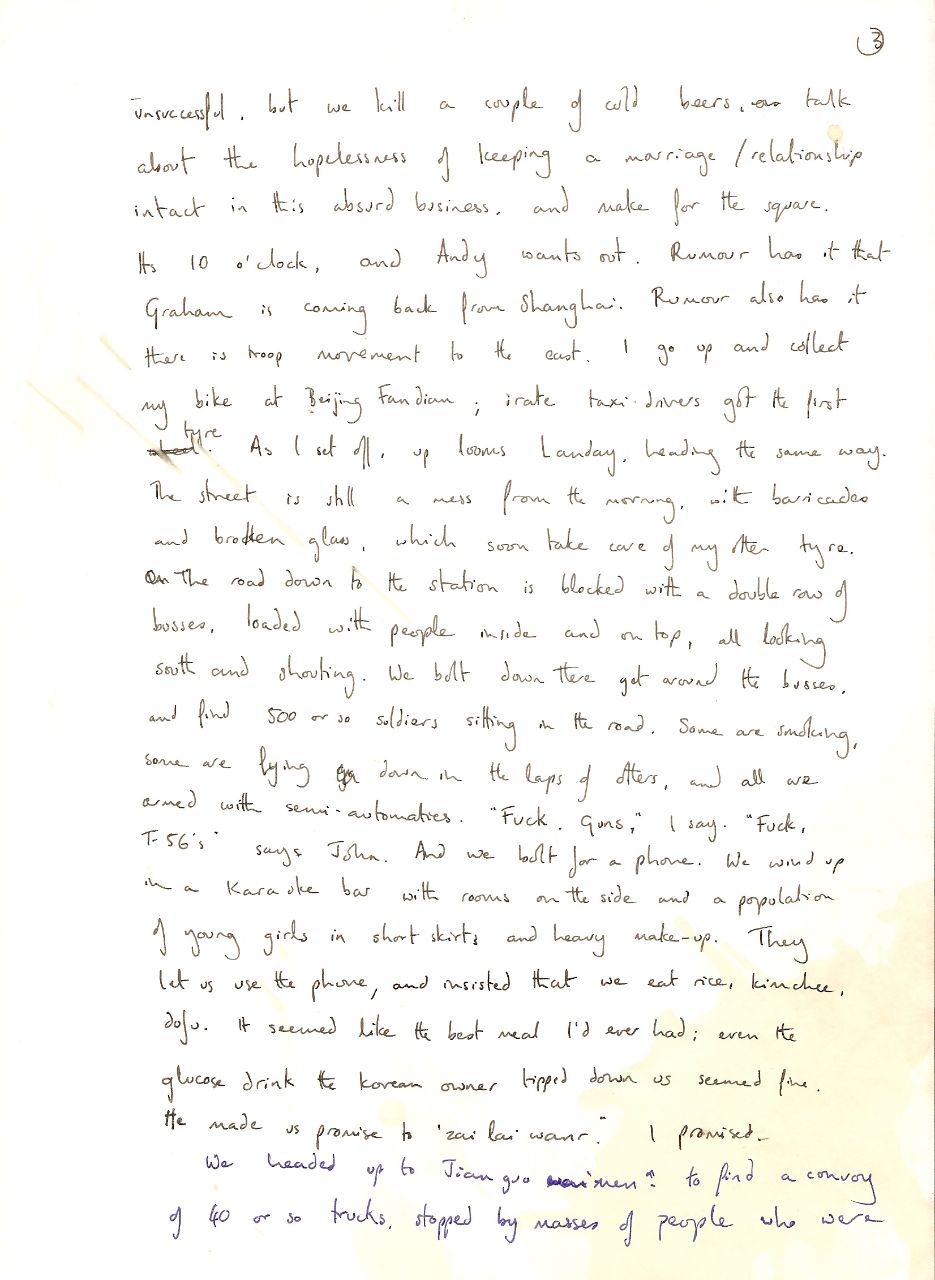

A little further south, outside the main steps on the west side of the Hall is the circle of soldiers. It is warm, they have been out here for hours: most are sitting down. In the interior circle are students, negotiating. They give the soldiers water and cigarettes. On one side, workers are singing the internationale, and after much prompting persuade some of the soldiers to do a patriotic number. Perched on the corner of a tricycle I see a student come forward with a bull horn and an important-looking officer. They announce a deal; the 10,000 or so troops that guy commands will not come out of the Hall again for forty-eight hours. Much rejoicing. The crowd reluctantly goes away, and soldiers file back into the Hall. Michael Fatters and Landay have rocked up – Michael is keen on the drink option but my conscience does a number on me and I dive down a back street with Landay to find a phone. (Mine is playing Silly Buggers.) Our subsequent quest for food is miserably unsuccessful, but we kill a couple of cold beers, talk about the hopelessness of keeping a marriage/relationship intact in this absurd business, and make for the square. Its ten o’clock, and Andy wants out. Rumour has it that Graham is coming back from Shanghai. Rumour also has it there is troop movement to the east. I go up and collect my bike at Beijing Fandian; irate taxi drivers got the first tyre. As I set off, up looms Landay, heading the same way. The street is still a mess from the morning, with barricades and broken glass, which soon take care of my other tyre. The road down to the station is blocked with a double row of buses, loaded with people inside and on top, all looking south and shouting. We bolt down there get around the buses, and find five hundred or so soldiers sitting in the road. Some are smoking, some are lying down in the laps of others, and all are armed with semi-automatics. ‘Fuck Guns,’ I say. ‘Fuck T-56’s,’ says John. And we bolt for a phone. We wind up in a Karaoke bar with rooms on the side and a population of young girls in short skirts and heavy make-up. They let us use the phone, and insisted that we eat rice, kimchee, tofu. It seemed like the best meal I’d ever had; even the glucose drink the Korean owner tipped down us seemed fine. He made us promise to ‘zai lai wanr’. I promised.

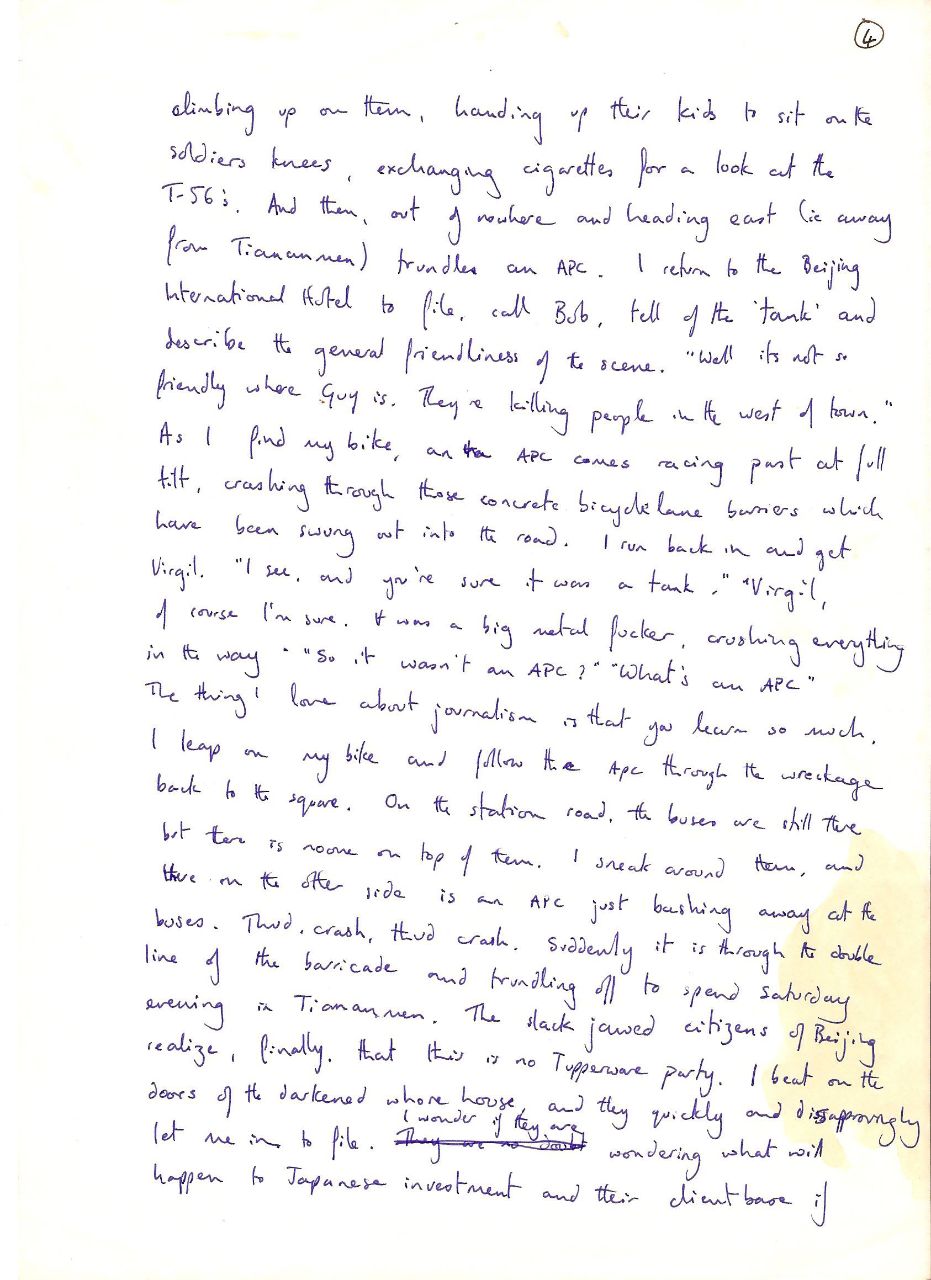

We headed up to Jian guo men to find a convoy of forty or so trucks, stopped by masses of people who were climbing up on them, handing up their kids to sit on the soldiers’ knees, exchanging cigarettes for a look out the T-56’s. And then, out of nowhere and heading east (ie, away from Tianemen) trundles and APC. I return to the Beijing International Hotel to file, call Bob, tell of the ‘tank’ and describe the general friendliness of the scene. ‘Well it’s not so friendly where Guy is. They’re killing people in the west of town.’ As I find my bike, an APC comes racing past at full tilt, crashing through those concrete bicycle lane barriers which have been swung out into the road. I run in and get Virgil. ‘I see, and you’re sure it was a tank.’ ‘Virgil, of course I’m sure. It was a big metal fucker, crushing everything in its way.’ ‘So it wasn’t an APC?’ ‘What’s an APC?’ The thing I love about journalism is that you learn so much. I leap on my bike and follow the APC through the wreckage back to the square. On the station road, the buses are still there but there is no one on top of them. I sneak around them, and there on the other side is an APC just bashing away at the houses. Thud, crash, thud, crash. Suddenly it is through the double line of the barricade and trundling off to spend Saturday evening in Tiananmen. The slack jawed citizens of Beijing realize, finally, that this is no Tupperware party. I beat on the doors of the darkened whore house, and they quickly and disapprovingly let me in to file. I wonder if they are wondering about what will to happen to Japanese investment and their client base if the worst comes to the worst.

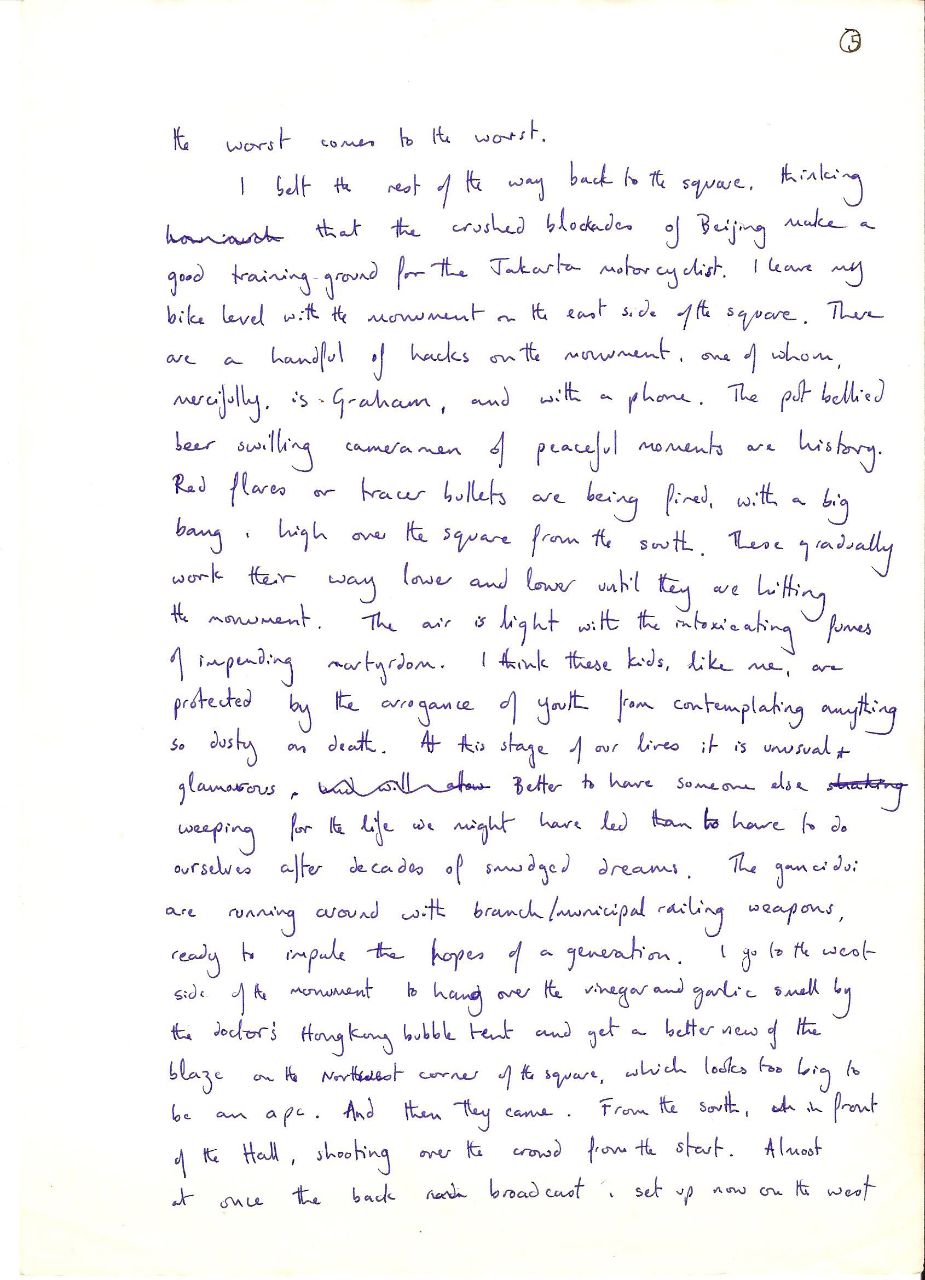

I belt the rest of the way back to the square. Thinking that the crushed blockades of Beijing make a good training ground for the Jakarta motorcyclist. I leave my bike level with the monument with the east side of the square. There are a handful of hacks on the monument, one of whom, mercifully, is Graham, and with a phone. The pot bellied beer swilling cameramen of peaceful moments are history. Red flares or tracer bullets are being fired, with a big bangs, high over the square from the south. These gradually work their way lower and lower until they are hitting the monument. The air is light with the intoxicating fumes of impending martyrdom. I think these kids, like me, are protected by arrogance of youth from contemplating anything so dusty on death. At this stage of our lives it is unusual and glamorous. Better to have someone else weeping for the life we might have led that to have to do ourselves alter decades of smudged dreams. The gancidui are running around with branch/municipal railing weapons, ready to impale the hopes of a generation. I go to the west side of the monument to hang over the vinegar and garlic smell by the doctor’s Hong Kong bubble tent and get a better view of the blaze on to the northeast corner of the square, which looks too big to be an APC. And then they came. From the south, in front of the Hall, shooting over the crowd from the start. Almost at once the back broadcast, set up now on the west of the monument, starts appealing to the soldiers’ humanity and brotherhood. More firing. Now trucks start pouring in to the north of the square from the west, maybe fifty of them.

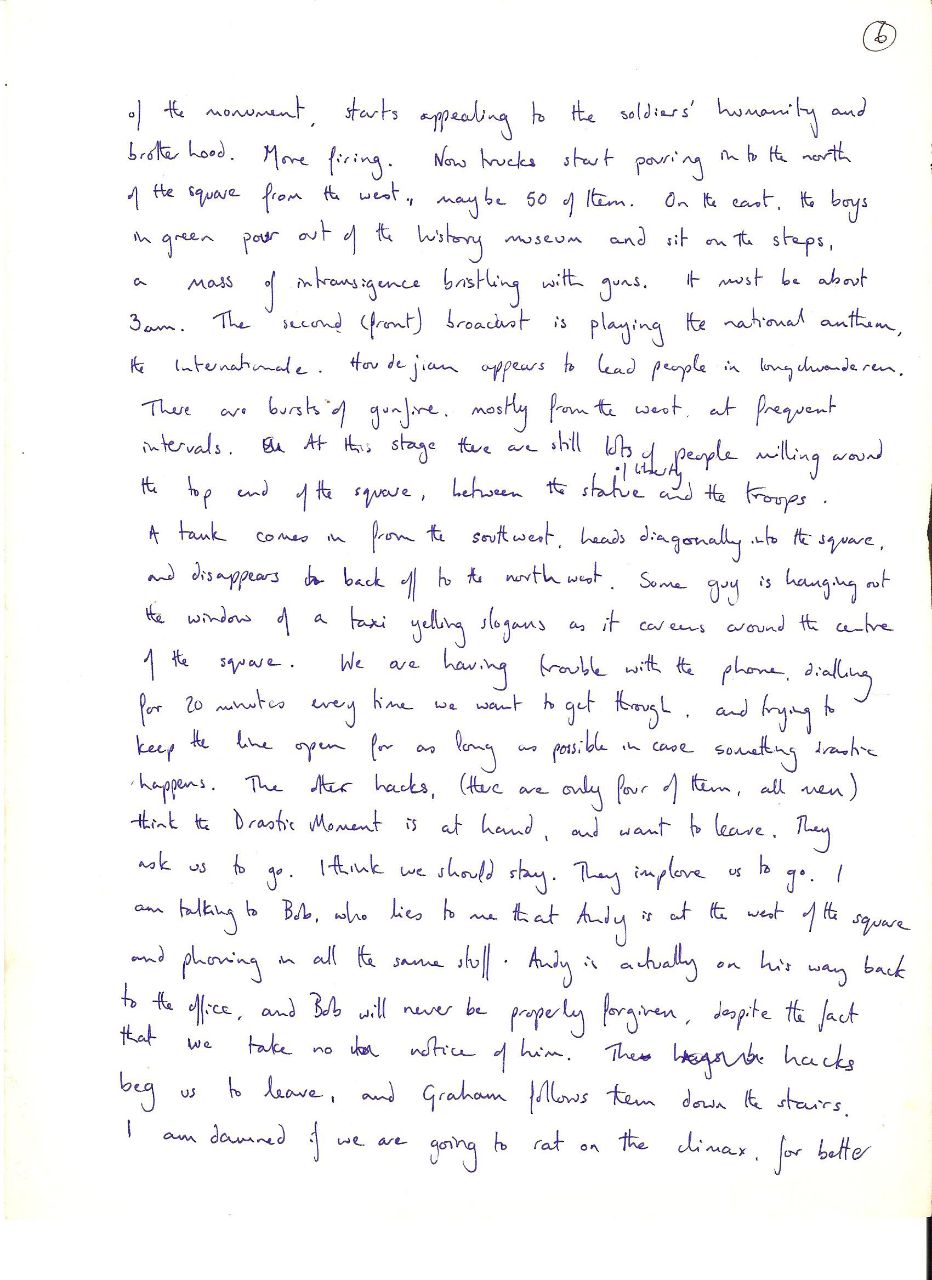

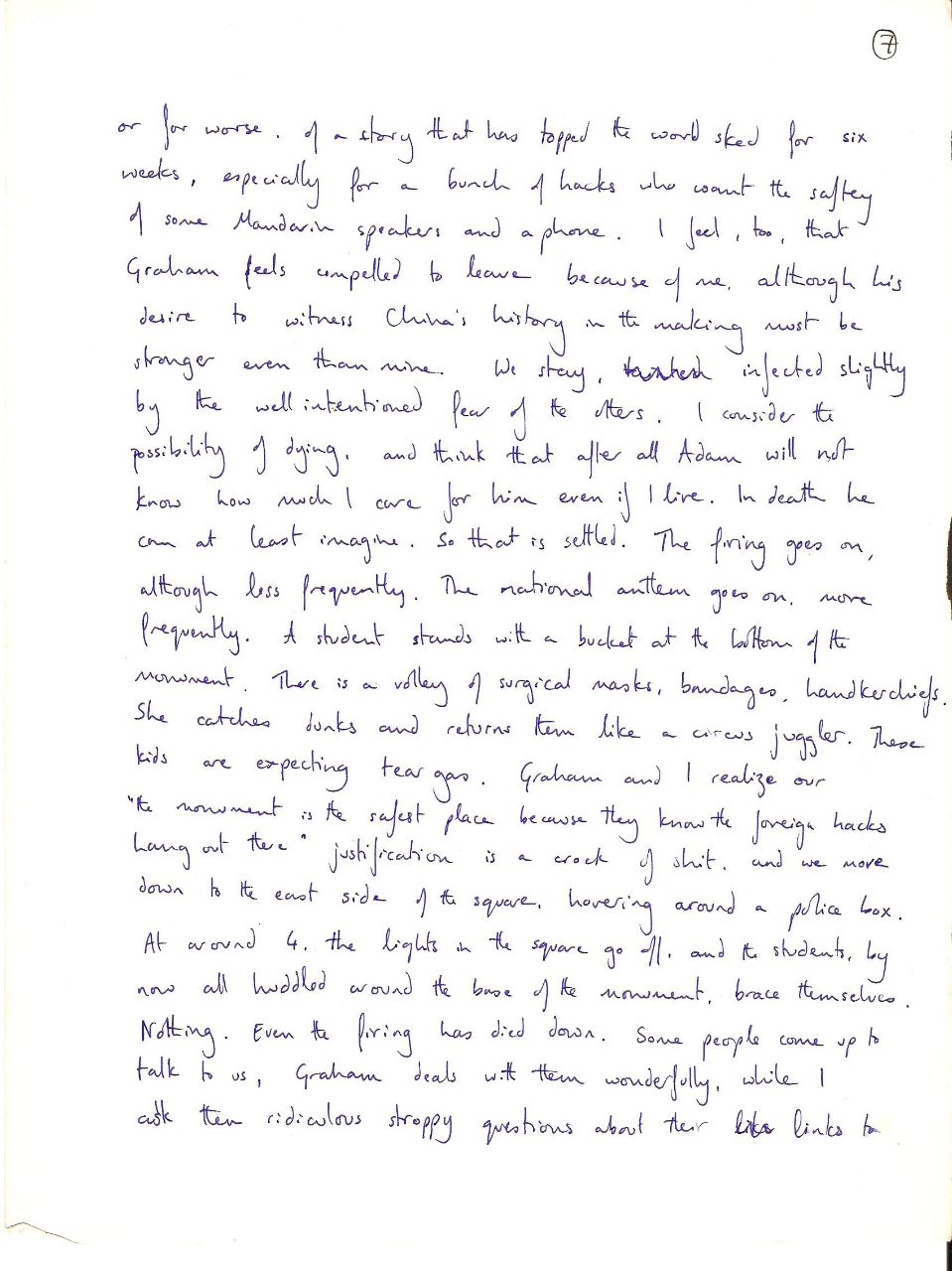

On the east, the boys in green pour out of the history museum and sit on the steps, a mass of intransigence bristling with guns. It must be about 3 a.m. The second (front) broadcast is playing the national anthem, the internationale. Hou de jian appears to lead the people in longchuanderen. There are bursts of gunfire, mostly from the west at frequent intervals. At this stage there are still lots of people milling around the top end of the square, between the statue of liberty and the troops. A tank comes in from the southwest, heads diagonally into the square and disappears back off to the northwest. Some guy is hanging out the windows of a taxi yelling slogans as it careers around the centre of the square. We are having trouble with the phone, dialling for twenty minutes every time we want to get through, and trying to keep the line open for as long as possible in case something drastic happens. The other hacks (there are only four of them, all men) think the Drastic Moment is at hand, and want to leave. They ask us to go. I think we should stay. They implore us to go. I am talking to Bob, who lies to me that Andy is at the west of the square and phoning in all the same stuff. Andy is actually on his way back to the office, and Bob will never be properly forgiven, despite the fact that we take no notice of him. The hacks beg us to leave, and Graham follows them down the stairs. I am damned if I am going to rat on the climax, for better or for worse, of a story that has topped the world sked for six weeks, especially for a bunch of hacks who count the safety of some Mandarin speakers and a phone. I feel, too, that Graham feels compelled to leave because of me, although his desire to witness China’s history in the making must be stronger even than mine. We stay, infected slightly by the well intentioned fear of the others. I consider the possibility of dying, and think that after all Adam will not know how much I care for him even if I live. In death he can at least imagine. So that is settled. The firing goes on, although less frequently. A student stands with a bucket at the bottom of the monument. There is a volley of surgical masks, bandages, handkerchiefs. She catches, dunks and returns them like a circus juggler. These kids are expecting tear gas. Graham and I realize our ‘the monument is the safest place because they know the foreign hacks hang out there’ justification is a crock of shit, and we move down to the east side of the square, hovering around a police box.

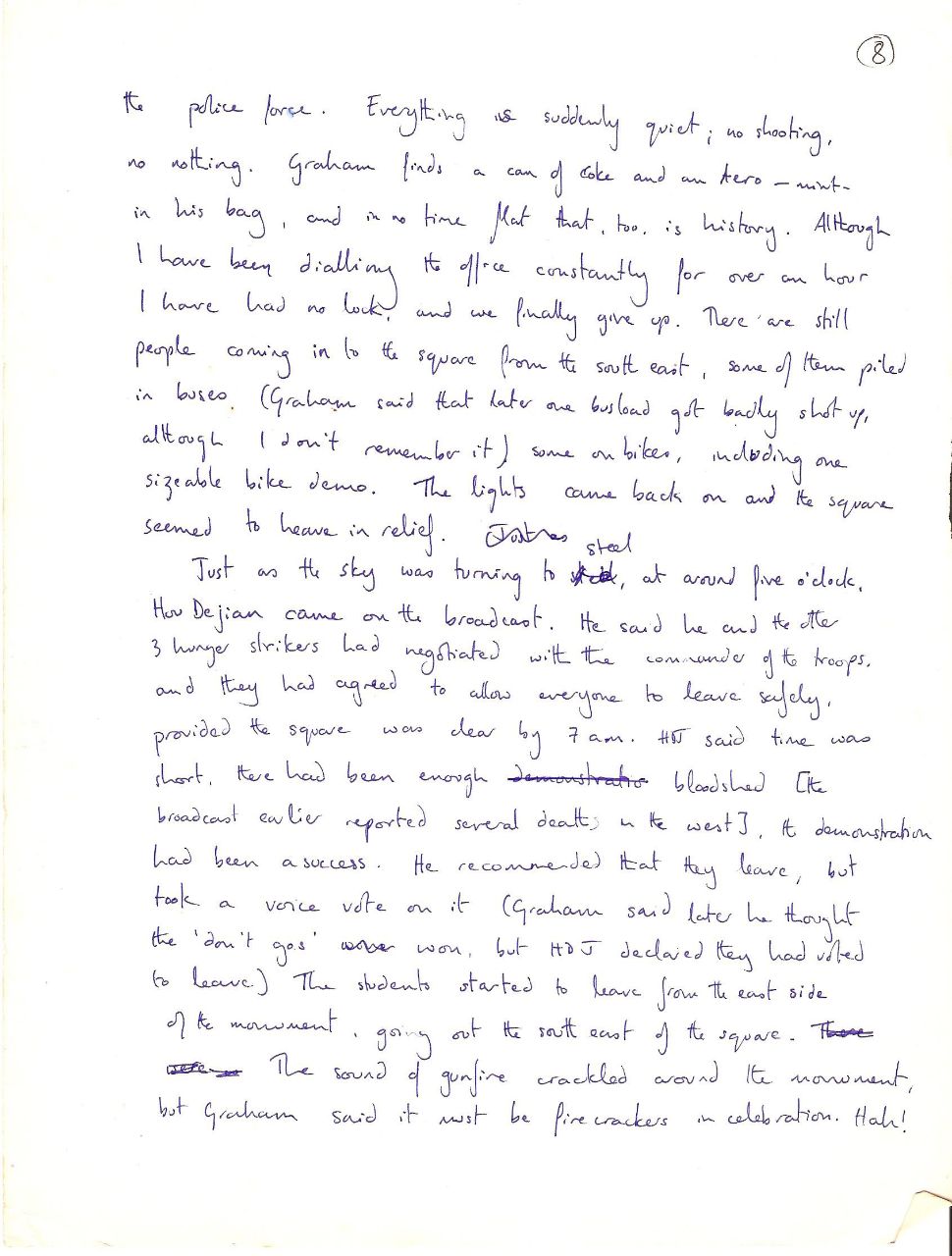

At around four, the lights in the square go off, and the students, by now all huddled around the base of the monument, brace themselves. Nothing. Even the firing has died down. Some people come up to talk to us. Graham deals with them wonderfully, while I ask them ridiculous stroppy questions about their links to the police force. Everything is suddenly quiet; no shooting, no nothing. Graham finds a can of Coke and an Aero – mint – in his bag, and in no time flat that, too, is history. Although I have been dialling the office constantly for over an hour I have had no luck, and we finally give up. There are still people coming in to the square from the south east, some of them piled in buses (Graham said that later one busload got badly shot up, although I don’t remember it), some on bikes, including one sizeable bike demo. The lights came back on and the square seemed to heave in relief.

Just as the sky was turning to steel, at around five o’clock, Hou Dejian came on the broadcast. He said he and the other three hunger strikers had negotiated with the commander of the the troops, and they had agreed to to allow everyone to leave safely, provided the square was clear by 7 a.m. Hou said time was short, there had been enough bloodshed (the broadcast earlier reported several deaths in the west), the demonstration had been a success. He recommended that they leave, but took a voice vote on it (Graham said later he thought the ‘don’t gos’ won, but Hou declared they had voted to leave). The students started to leave from the east side of the monument, going out the south east of the square. The sound of gunfire crackled around the monument, but Graham said it must be fire crackers in celebration. Ha!

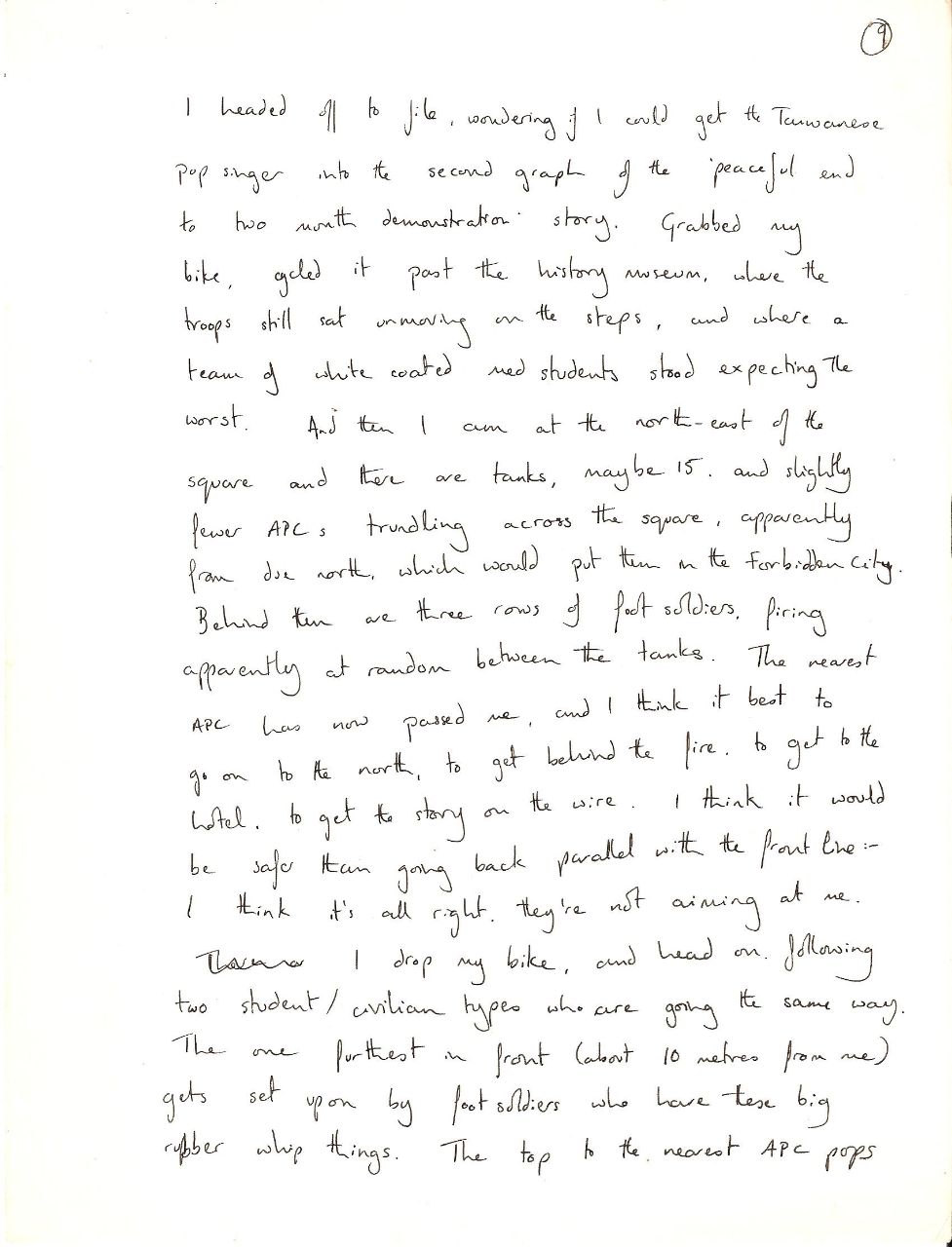

I headed off to file, wondering if I could get the Taiwanese pop singer into the second graph of the ‘peaceful end to two month demonstration’ story. Grabbed my bike, cycled it past the history museum, where the troops still sat unmoving on the steps, and where a team of white coated med students stood expecting the worst. And then I am at the northeast of the square and there are tanks, maybe fifteen, and slightly fewer APCs trundling across the square, apparently from due north, which would put them in the Forbidden City. Behind them are three rows of foot soldiers, firing apparently at random between the tanks. The nearest APC has now passed me, and I think it best to go on to the north, to get behind the fire, to get to the hotel, to get the story on the wire. I think it would be safer than going back parallel with the front line – I think it’s all right. They’re not aiming at me. I drop my bike, and head on, following two student/civilian types who are going the same way. The one furthest in front (about ten metres from me) gets set upon by foot soldiers who have these big rubber whip things. The top to the nearest APC pops open, a couple of shots dance around the three of us, and the second chap, about five metres in front of me, goes down. I turn tail. By the time I am level with the history museum, the med students are loading limp bodies onto makeshift stretchers and into ambulances. For the fifteen minutes that I am around after this, the stream of bodies, stretchers, ambulances is more or less constant. At a distance of even a metre it is hard to tell an unconscious body from a corpse, and I cannot swear before my heart that several dozen people died on the square. I can and did save my only tears for the inevitable moment when official television announced 在 天安门广场 没有一 人死.

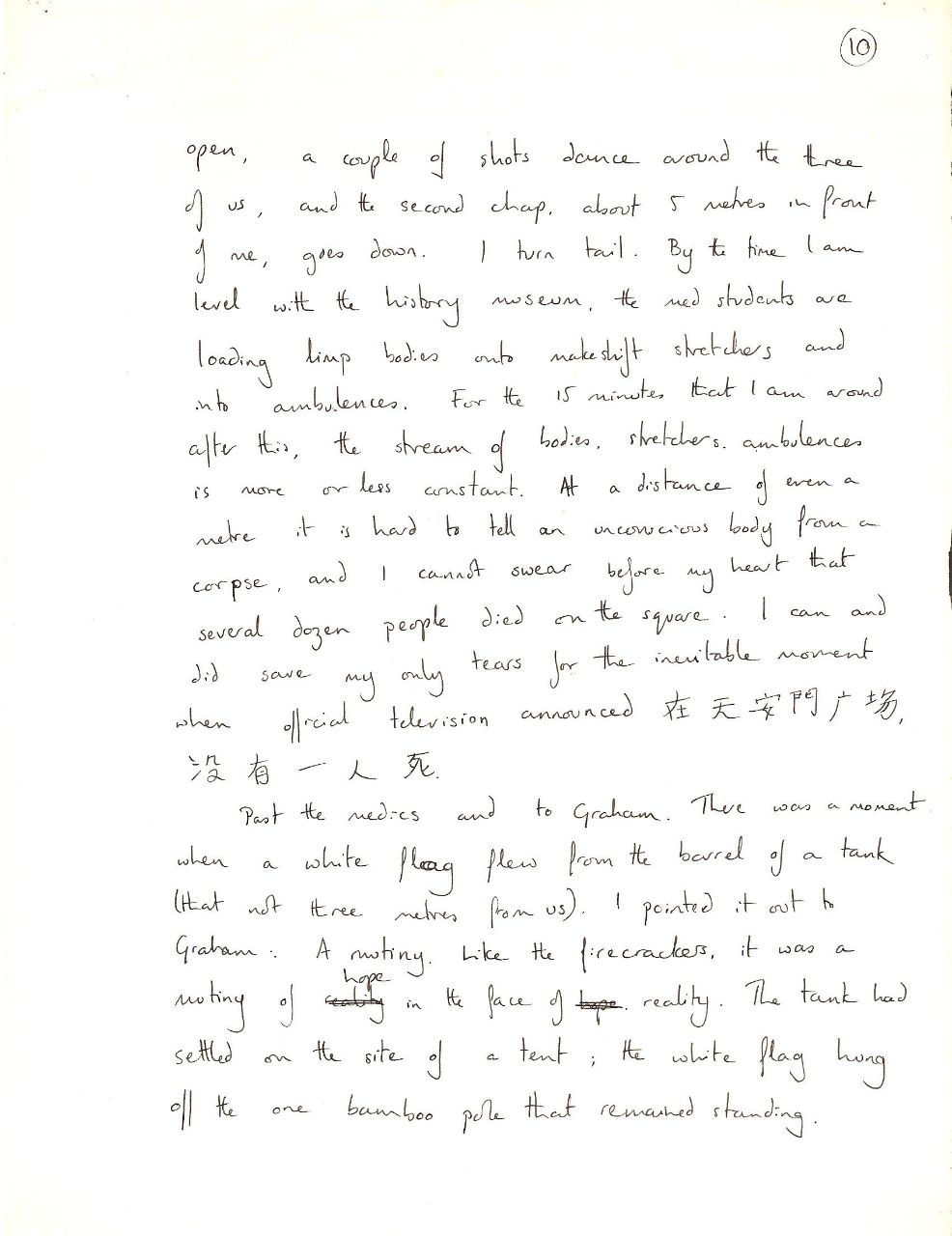

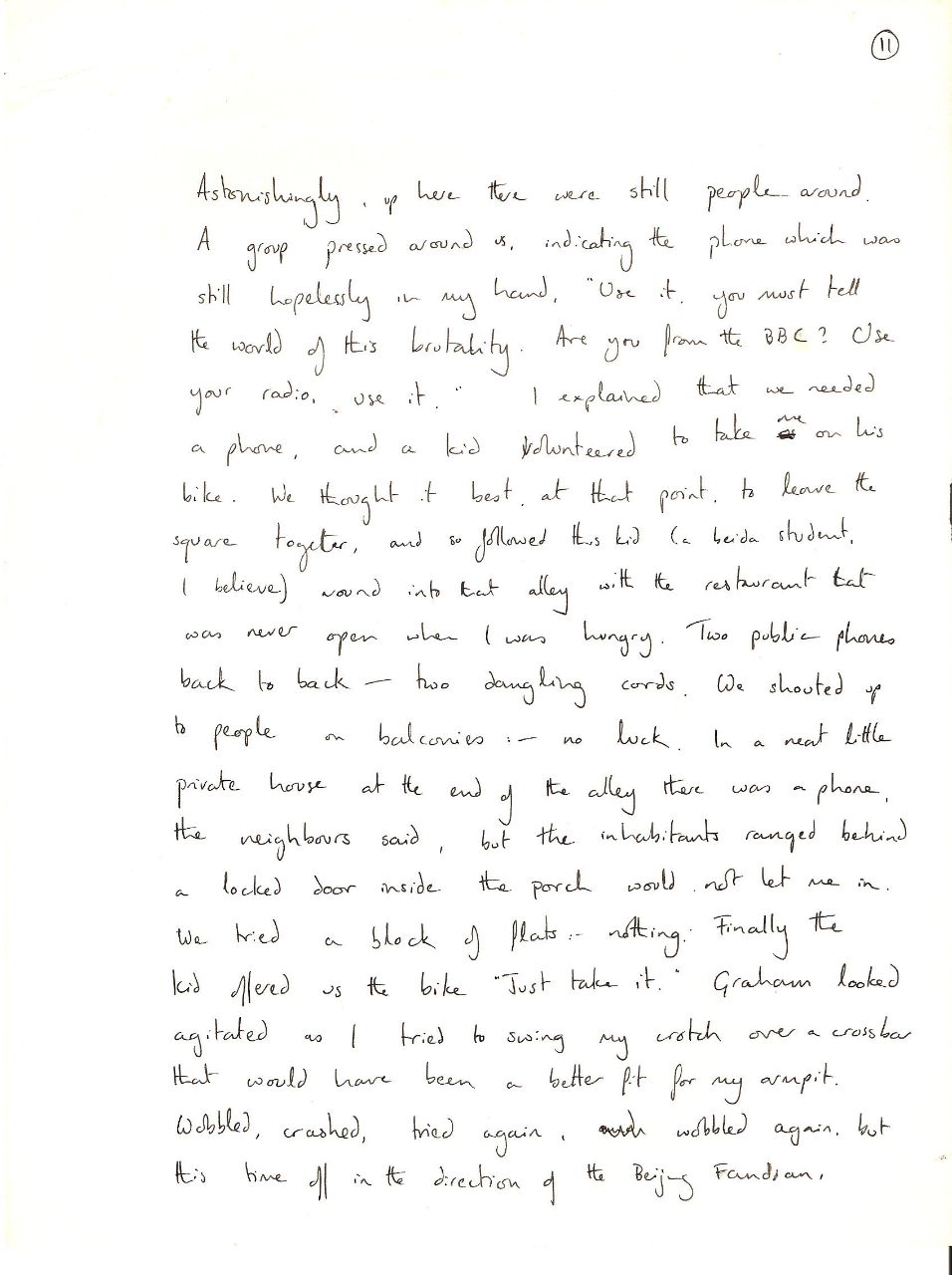

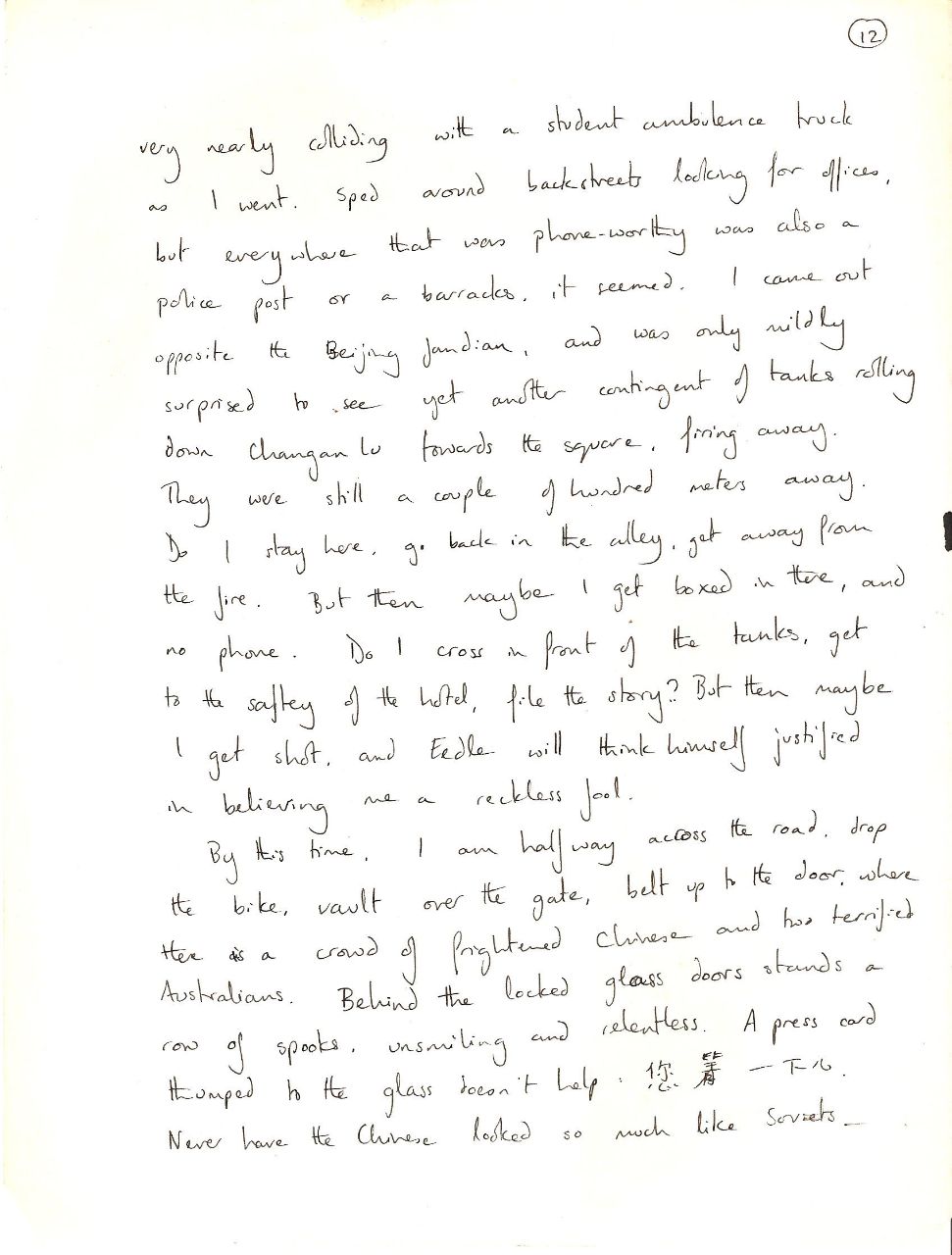

Past the medics and to Graham. There was a moment when a white flag flew from the barrel of a tank (that not three metres from us). I pointed it out to Graham. A mutiny. Like the firecrackers, it was a mutiny of hope in the face of reality. The tank had settled on the site of a tent; the white flag hung off the one bamboo pole that remained standing. Astonishingly, up here there were still people around. A group pressed around us, indicating the phone which was still hopelessly in my hand, ‘Use it, you must tell the world of this brutality. Are you from the BBC? Use your radio, use it.’ I explained that we needed a phone, and a kid volunteered to take me on his bike. We thought it best, at that point, to leave the square together, and so followed this kid (a beida student, I believe) wound into that alley with the restaurant that was never open when I was hungry. Two public phones back to back – two dangling cords. We shouted up to people on balconies – no luck. In a neat little private house at the end of the alley there was a phone, the neighbours said, but the inhabitants ranged behind a locked door inside the porch would not let me in. We tried a block of flats – nothing. Finally the kids offered us the bike ‘Just take it.’ Graham looked agitated as I tried to swing my crotch over a crossbar that would have been a better fit for my armpit. Wobbled, crashed, tried again, wobbled again, but this time all in the direction of the Beijing Fandian, very nearly colliding with a student ambulance truck as I went. Sped around backstreets looking for offices, but everywhere that was phone-worthy was also a police post or a barracks, it seemed. I came out opposite the Beijing Famdian, and was only mildly surprised to see yet another contingent of tanks rolling down Changan Lu towards the square, firing away. They were still a couple of hundred meters away. Do I stay here, go back in the alley, get away from the fire. But then maybe I get boxed in there, and no phone. Do I cross in front of the tanks, get to the safety of the hotel, file the story? But then maybe I get shot, and Eedle will think himself justified in believing me a reckless fool.

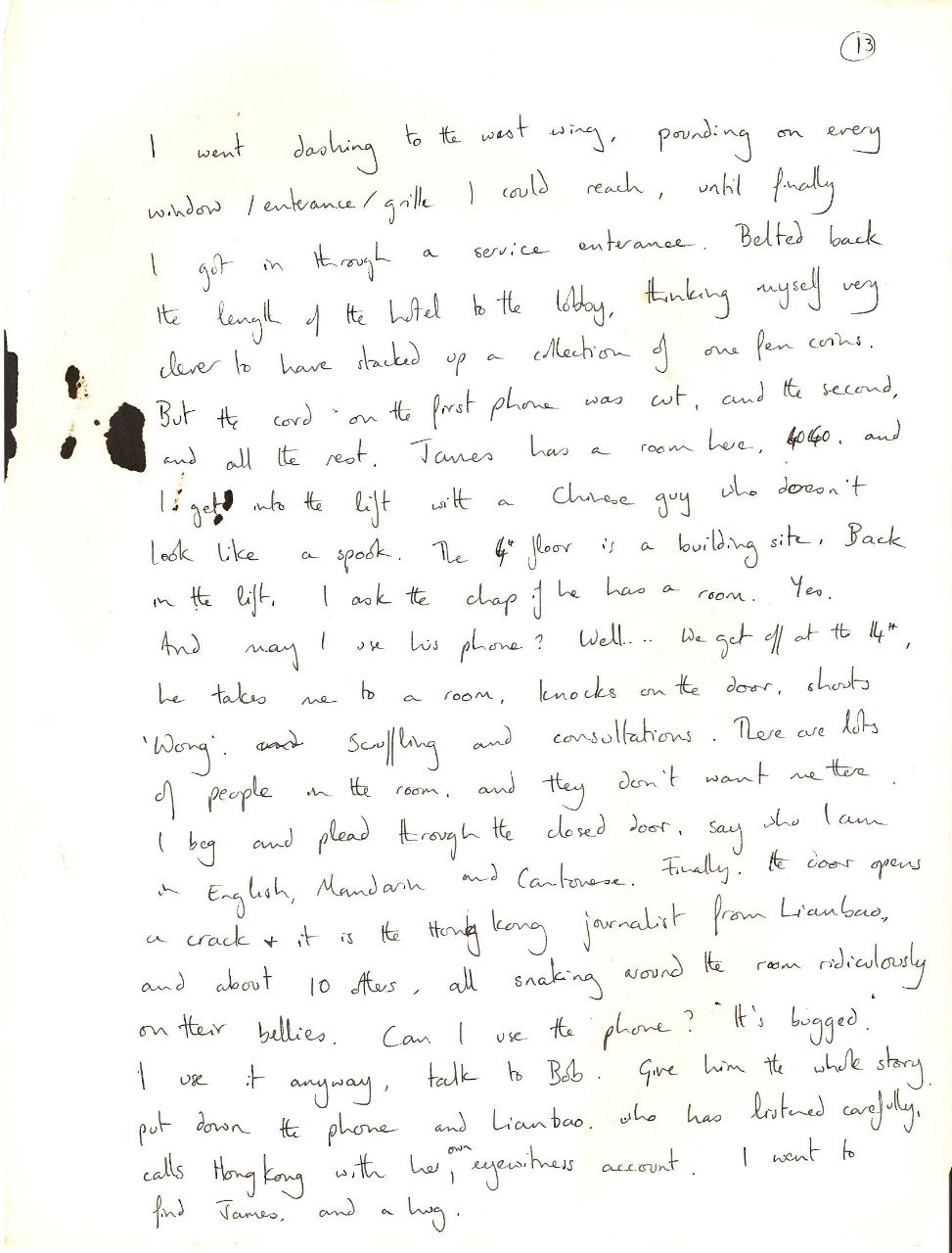

By this time, I am halfway across the road, drop the bike, vault over the gate, bolt up to the door, where there is a crowd of frightened Chinese and two terrified Australians. Behind the locked glass doors stands a row of spooks, unsmiling and relentless. A press card thumped to the glass doesn’t help: 你等一下儿. Never have the Chinese looked so much like Soviets. I went dashing to the west wing, pounding on every window/entrance/grille I could reach, until finally I got in through a service entrance. Belted back the length of the hotel to the lobby, thinking myself very clever to have stacked up a collection of one yen coins. But the cord on the first phone was cut, and the second, and all the rest. James has a room here, 4060, and I get into the lift with a Chinese guy who doesn’t look like a spook. The fourth floor is a building site. Back to life, I ask the chap if he has a room. Yes. And may I use his phone? Well . . . We get off at the fourteenth, he takes me to a room, knocks on the door, shouts ‘Wong.’ Scuffling and consultations. There are lots of people in the room, and they don’t want me there. I beg and plead through the closed door, say who I am in English, Mandarin and Cantonese. Finally, the door opens a crack, it is the Hong Kong journalist from Lianbao, and about ten others, all snaking around the room ridiculously on their bellies. Can I use the phone. ‘It’s bugged.’ I use it anyway, talk to Bob. Give him the whole story, put down the phone and Lianbao, who has listened carefully, calls Hong Kong with her own eyewitness account. I went to find James, and a hug!

To read more reflections from Pisani about the massacre, visit her website.

Photograph © Arian Zwegers, Beijing, Tiananmen Square, Great Hall of the People, 1995