Souvankham Thammavongsa is the author of three books of poetry: Small Arguments, Found and Light. We featured her story ‘How to Pronounce Knife’ in Granta 141: Canada. In this new series, we give authors a space to discuss the way they write – from technique and style to inspirations that inform their craft.

After the war in Vietnam ended, we were some of those three million refugees nobody wanted. My father built a raft made of bamboo to cross the Mekong River. I was born in the Lao refugee camp in Nong Khai, Thailand in 1978. I was born weighing two pounds. My father tells me that this is the size of a pop can. I did not have a birth certificate. Nothing that said I was born. ‘Stateless’ is the word given to someone like me. At the time, we did not know what would happen to us, what our future might look like. I was not supposed to be there, and no one expected me to live.

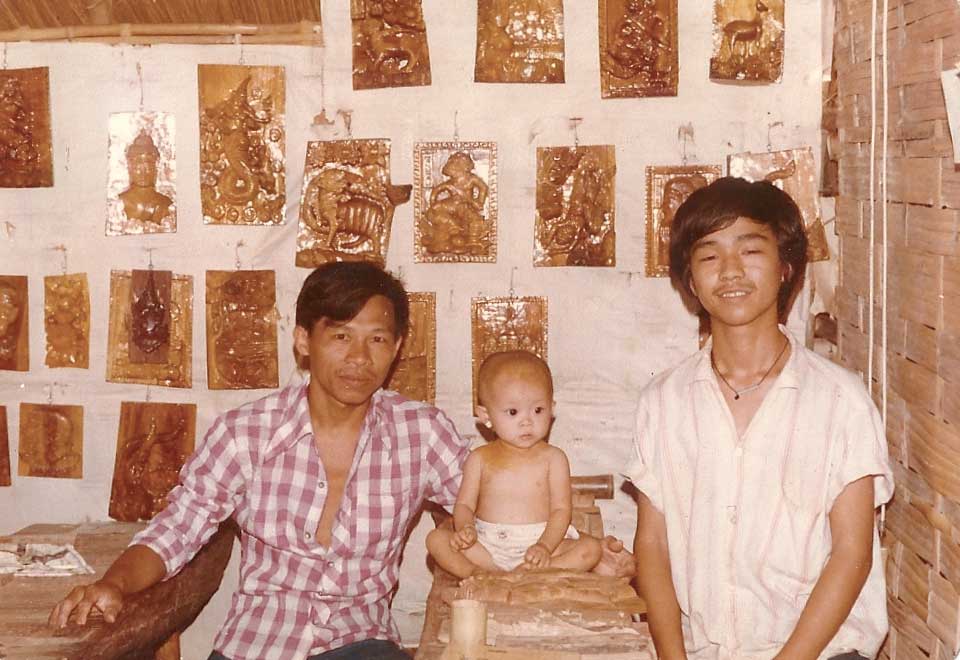

But nothing in this photograph shows that.

The photograph below is of a man and his art. There he is, in a refugee camp, surrounded by those things on the wall. Carved out of wood. Shining.

There is a child sitting next to him. That’s me. This man is my father. The man to the right is his friend. I watched my father carve those things all day. This is what he knew how to do in the world.

His friends were educated, with skills other countries demanded. This got them out of the refugee camp faster. But my father, he carved things out of wood. The things he made were admired, appreciated, but no one bought them. Everyone there was waiting to be some place else. Where that was, you didn’t know until you did. And then, you only took what little you had. Your clothes, some family pictures, documents, eating utensils. Wood is heavy. It was not a thing anyone wanted with them, and even if it had been, it was not a thing anyone could take with them. And yet all of those things hang on display behind us, as if some day soon someone will want them. Each piece he made marked out the time he had, waiting in the refugee camp.

There are so many because we had been waiting so long.

I do not know what became of these wood carvings. When it was our turn to leave the camp, my father left them behind. He took only the tools. It was not the final products he thought about, but the tools with which to make them. The tools could make these things again.

What he carved came out of a flat surface, a block of wood. He carved out animals, elephants and tigers, Buddha, hands held in prayer, dancing bodies, and faces – people with faces like ours. He had to imagine them, see that they could be when they were not there yet. What no one sees, in the end, are the wood bits he had to carve out to get to them. Those things fell to the floor; we do not see them up on the wall.

I grew up in a home without books. There are other photographs of me in front of bookshelves at the library or at the home of our friends. I did not know what these things were, but I knew we did not have them. When I got the chance, I always asked to be photographed with them. What words there were at home came from newspaper print, which we did not read. We used newspaper to dry our winter boots or wrap things made of glass.

Later on, there would be an English dictionary and I would come to see this big book as my father did his own work. These are all the wood bits I have to carve through to get what I want to make. When I look at a word, I can see the thing inside it. The ear inside heart. And I can see the sound of the letters even when we do not say them, the agreement we make to keep silent what is visible in a word like ‘knife’. When I look at my mother’s name, Sisouvanh, I see the beginning of my own name in the middle of it. Both our names do not exist in that book. It is not that we have no meaning. All these words and names come from somewhere, they have their own stories, and I am looking for them.

When I make things, I know they are taken to be quiet and small. I know there may be no place for them. I know no one is waiting for them. I know it may be that no one wants them. But I must make them. I must.

I learn from this photograph that you must make your art, wherever you are, whoever you are, whatever you have. You must. This is something no one can ever teach a writer. She must find this for herself alone. Over and over. This must.

In-text photograph courtesy of the author

Feature photograph © Renate Dodell