1

I have been thinking about Tomas for many years, but not until I saw him in the light of a new perception did I see him clearly. I saw him standing at the window of his flat and looking across the courtyard at the opposite walls, not knowing what to do.

He had first met Tereza about three weeks earlier in a small Czech town. They had spent scarcely an hour together. She had accompanied him to the station and waited with him until he boarded the train. Ten days later she paid him a visit. They made love the day she arrived. That night she came down with a fever, and stayed a whole week in his flat with the flu.

He had come to feel an inexplicable love for this all but complete stranger; she seemed a child to him, a child someone had laid in a bulrush basket daubed with pitch, and sent downstream for Tomas to fetch at the riverbank of his bed.

She stayed with him a week, until she was well again, then went back to her town, some hundred and twenty-five miles from Prague. And then came the moment I have just spoken of and see as the key to his life: standing by the window, he looked out over the courtyard at the walls opposite him and deliberated. Should he call her back to Prague for good? He feared the responsibility. If he invited her to come, she would come, and then offer her life to him.

Or should he resist approaching her? Then she would remain a waitress in the hotel restaurant of the provincial town and he would never see her again.

Did he want her to come or not?

He looked out over the courtyard at the opposite walls seeking an answer.

He kept recalling her lying on his bed; she reminded him of no one in his former life. She wasn’t a mistress or a wife; she was a child whom he had taken from a bulrush basket daubed with pitch. She fell asleep. He knelt down next to her. Her feverous breath quickened and she gave out a weak moan. He pressed his face to hers and whispered calming words into her sleep. After a while he felt her breath return to normal and her face rise unconsciously to meet his. He smelled the delicate aroma of her fever and breathed it in, as if trying to glut himself with the intimacy of her body. And all at once he fancied she had been with him for many years and was dying. He had a sudden clear feeling that he would not survive her death. He would lie down beside her and want to die with her. He pressed his face into the pillow beside her head and kept it there for a long time.

Now he was standing at the window trying to call that moment to account. What could it have been if not love declaring itself?

But was it love? The feeling of wanting to die beside her was clearly exaggerated: he had seen her only once before in his life. Wasn’t it only the hysteria of a man who, aware deep down of his inaptitude for love, felt the self-deluding need to simulate it? And was his unconscious so cowardly that the best partner it could choose for its little comedy was this miserable provincial waitress with practically no chance at all to enter his life?

Looking out over the courtyard at the dirty walls, he realized he had no idea whether it was hysteria or love.

And he was distressed that in a situation where a real man would have instantly known how to act, he was vacillating and therefore depriving the most beautiful moments he had ever experienced (kneeling at her bed and thinking he would not survive her death) of their meaning.

He remained annoyed with himself until he realized that not knowing what he wanted was actually quite natural: we can never know what to want, because, living only one life, we can neither compare it with our previous lives nor perfect it in our lives to come.

Is it better to be with Tereza or to remain alone?

There is no means of testing which decision is better, because there is no basis for comparison. We live everything as it comes, without warning, like an actor going on cold. And what can life be worth if the first rehearsal for life is life itself? That is why life is always like a sketch. No, sketch is not quite the word, because a sketch is an outline of something, the groundwork for a picture, whereas the sketch that is our life is a sketch for nothing, an outline with no picture.

Einmal ist keinmal, says Tomas to himself. What happens but once, says the German adage, might as well not have happened at all. If we have only one life to live, we might as well not have lived at all.

2

But then one day during a break from surgery, he was called to the telephone by a nurse. He heard Tereza’s voice coming from the receiver. She was phoning him from the station. He was overjoyed. Unfortunately he was busy that evening and could not invite her to his place until the next day. The moment he hung up, he reproached himself for not telling her to go straight there. He had time enough to cancel his plans, after all! He tried to imagine what Tereza would do in Prague for the thirty-six long hours before they were to meet, and had half a mind to jump into his car and drive through the streets looking for her.

She arrived the next evening, dangling a handbag over her shoulder and looking more elegant than the last time they met. She had a thick book under her arm. It was Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina. She seemed in a good mood, even a little boisterous, and tried to make him think she had just happened to drop in, things had just worked out that way: she was in Prague on business, perhaps (at this point she became rather vague) to find a job.

Later, as they lay naked and spent side by side on the bed, he asked her where she was staying. It was night by then, and he offered to drive her there. Embarrassed, she answered that she still had to find a hotel and had left her suitcase at the station.

Only the day before he had feared that if he invited her to Prague she would offer her life to him. When she told him her suitcase was at the station, he realized in an instant that the suitcase contained her life and that she had left it at the station only until she could offer it to him.

The two of them got into his car, which was parked in front of the house, and drove to the station. There he claimed the suitcase (which was large and enormously heavy) and took both it and Tereza home with him.

How had he come to make such a sudden decision when for nearly a fortnight he had wavered so much he could not even bring himself to send a postcard asking her how she was?

He himself was surprised. He was acting against his own principles. Ten years earlier, when he had divorced his first wife, he had celebrated the event the way others celebrate a marriage. He had come to believe that he was not born to live side by side with any woman and could be fully himself only as a bachelor. He tried to design his life in such a way that no woman could move in with a suitcase. That was why his flat had only the one bed. And even though it was quite a wide bed, Tomas would tell his mistresses that he was unable to fall asleep with anyone next to him, and drive them home after midnight. And so, on Tereza’s first visit, it was not because of the flu that he avoided sleeping with her. The first night he spent in his large armchair, and the rest of that week he drove every night to the hospital, where he had a cot in his office for night shifts.

But this time he fell asleep by her side. When he woke up the next morning he found Tereza, who was still asleep, holding his hand. Could they have been hand in hand all night? It was hard to believe.

And while she breathed the deep breath of sleep and held his hand (firmly – he was unable to disengage it from her grip), the enormously heavy suitcase stood watch by the bed.

He refrained from loosening his hand from her grip for fear of waking her, and turned carefully on his side to observe her better.

Again it occurred to him that Tereza was a child laid in a pitch-daubed bulrush basket and sent downstream. He couldn’t very well let a basket with a child in it float down a stormy river! If the Pharaoh’s daughter hadn’t snatched the basket carrying little Moses from the waves, there would have been no Old Testamant, no civilization as we know it! How many ancient myths begin with the rescue of an abandoned child! If Polybus hadn’t taken in the young Oedipus, Sophocles wouldn’t have written his most glorious tragedy!

Tomas did not realize at the time that metaphors are dangerous. Metaphors are not to be trifled with. A single metaphor can give birth to love.

3

He lived a scant two years with his first wife and they had a son. At the divorce proceedings, the judge awarded the child to its mother and ordered Tomas to pay a third of his salary for its support. He also granted him the right to visit the boy every other week.

But each time Tomas was supposed to see him, the boy’s mother found an excuse to keep him away. He soon realized that bringing them expensive gifts would make things a good deal easier, that he was expected to bribe the mother for the son’s love. He saw himself making quixotic attempts to inculcate his views in the boy, views opposed in every way to the mother’s. The very thought of it exhausted him. When, one Sunday, the boy’s mother again cancelled a scheduled visit, Tomas decided never to see him again.

Why should he feel more for that chifd, to whom he was bound by nothing but a single improvident night, than for any other? He would be scrupulous about paying support; he just didn’t want anybody making him fight for the boy in the name of paternal sentiments.

Needless to say, he found no sympathizers. His own parents condemned him roundly: if Tomas refused to take an interest in his son, then they, Tomas’s parents, would no longer take an interest in theirs. They made a great show of maintaining good relations with their daughter-in-law and trumpeted their exemplary stance and sense of justice.

Thus in practically no time Tomas managed to rid himself of wife, son, mother, and father. The only thing they bequeathed to him was a fear of women. He desired them, but feared them. And feeling the need to fashion a compromise between fear and desire, he invented erotic friendship. As he would tell his mistresses: the only relationship that can make both partners happy is one in which sentimentality has no place and neither partner makes any claim on the life and freedom of the other.

To ensure that erotic friendship never grew into aggressive love, he would meet each of his long-term mistresses only at intervals. He considered this method flawless and propagated it among his friends: ‘The important thing is to abide by the rule of threes. Either you see a woman three times in quick succession and then never again, or you maintain your relationship over a number of years, but make sure the rendezvous are at least three weeks apart.’

The rule of threes enabled Tomas to keep intact his liaisons with some women while continuing to engage in short-term affairs with many others. He was not always understood. The woman who understood him best was Sabina. She was a painter.

It was Sabina he turned to when he needed to find a job for Tereza in Prague. Following the unwritten rules of erotic friendship, she promised to do everything in her power, and before long she had located a place for her in the darkroom of an illustrated weekly. Although her new job did not require any particular qualifications, it raised her status from waitress to member of the press. And when Sabina herself then went on to introduce Tereza to everyone on the weekly, Tomas knew he had never had a better friend for a mistress than Sabina.

4

The unwritten contract of erotic friendship stipulated that Tomas exclude all love from his life. The moment he violated that clause of the contract, his other mistresses would assume inferior status and become ripe for insurrection.

Accordingly, he rented a room for Tereza and her heavy suitcase. He wanted to be able to watch over her, protect her, enjoy her presence, but felt no need to change his way of life. He did not want word to get out that Tereza was sleeping at his place: spending the night together was the corpus delicti of love.

He never spent the night with the others. After making love he had an uncontrollable craving to be by himself. Waking in the middle of the night at the side of an alien body was distasteful to him, and rising in the morning with an intruder was repellent. He had no desire to be overheard brushing his teeth in the bathroom, nor was he enticed by the thought of an intimate breakfast.

That is why he was so surprised to wake up and find Tereza squeezing his hand so tightly. Lying there looking at her, he could not quite understand what had happened. But as he ran through the previous few hours in his mind, he began to sense an aura of hitherto unknown happiness emanating from them.

From that time on they both looked forward to sleeping together. I might even say that the goal of their love-making was not so much orgasm as the sleep that followed it. She especially was affected. Whenever she stayed overnight in her rented room (which quickly became only an alibi for Tomas) she was unable to fall asleep. In his arms she would fall asleep no matter how wrought up she might have been. He would whisper impromptu fairy tales about her, or gibberish, words he repeated monotonously, words soothing or comical, which turned into vague visions lulling her through the first dreams of the night. He had complete control over her sleep: she dozed off at the second he chose.

While they slept, she held him as on the first night, keeping a firm grip on wrist, finger or ankle. If he wanted to move without waking her, he had to resort to artifice. After freeing his finger (wrist or ankle) from her clutches– – a process which never failed to rouse her partially, as she guarded him carefully even in her sleep – he would calm her by slipping an object into her hand (a rolled-up pyjama top, a slipper, a book), which she then gripped as tightly as if it were a part of his body.

Once, when he had just lulled her to sleep but she had gone no farther than dream’s antechamber and was therefore still responsive to him, he said to her, ‘Goodbye, I’m going now.’

‘Where?’ she asked, still in her sleep.

‘Away,’ he answered sternly.

‘Then I’m going with you,’ she said, sitting up in bed.

‘No, you can’t. I’m going away for good,’ he said, going out into the hall. She stood up and followed him out, squinting. She was naked beneath her short nightdress. Her face was blank, expressionless, but she moved energetically. He walked through the hall of the flat into the hall of the building (the hall shared by all the occupants), closing the door in her face. She flung it open and continued to follow him, convinced in her sleep that he meant to leave her for good and she had to stop him. He walked down the stairs to the first landing and waited for her there. She went down after him, took him by the hand, and led him back to bed.

It was then that Tomas came to the conclusion that making love with a woman and sleeping with a woman are two separate passions, not merely different but near opposites. Love does not make itself felt in the desire for copulation (which desire extends to an infinite number of women) but in the desire for shared sleep (which desire is limited to one woman).

5

In the middle of the night she started moaning in her sleep. Tomas woke her up, but when she saw his face she said, with hatred in her voice, ‘Get away from me! Get away from me!’ Then she told him her dream: the two of them and Sabina had been in a big room together. There was a bed in the middle of the room. It was like a podium in the theatre. Tomas ordered her to stand in the corner while he made love to Sabina. The sight of it caused Tereza intolerable suffering. Hoping to alleviate the pain in her heart by pains of the flesh, she jabbed needles under her fingernails. ‘It hurt so much,’ she said, squeezing her hands into fists as if they actually were wounded.

He pressed her to him, and she gradually (trembling violently for a long time) fell asleep in his arms.

Thinking about the dream the next day, he remembered something. He opened a desk drawer and took out a packet of letters Sabina had written to him. He was not long in finding the following passage: ‘I want to make love to you in my studio. It will be like a stage surrounded by people. The audience won’t be allowed up close, but they won’t be able to take their eyes off us….’

The worst of it was that the letter was dated. It was quite recent, written long after Tereza had moved in with Tomas.

‘So you’ve been rummaging in my letters!’

She did not deny it. ‘Throw me out then!’

But he did not throw her out. He could picture her pressed against the wall of Sabina’s studio jabbing needles up under her nails. He took her fingers between his hands and stroked them, brought them to his lips and kissed them, as if they still had drops of blood on them.

But from that time on everything seemed to conspire against him. Not a day went by without her learning something about his secret love life.

At first he denied it all. Then, when the evidence became too blatant, he argued that his polygamous way of life did not in the least run counter to his love for her. He was inconsistent: first he disavowed his infidelities, then he tried to justify them.

Once he was making a date with a woman on the phone, and as he said goodbye he heard a strange sound in the next room, a sound suggestive of teeth chattering loudly.

Tereza had happened to come home without his realizing it. She was pouring something from a medicine bottle down her throat, and her hand shook so badly the glass bottle clinked against her teeth.

He pounced on her as if trying to save her from drowning. The bottle fell to the ground, spotting the carpet with valerian drops. She put up a good fight, and he had to keep her in a straitjacket-like hold for a quarter of an hour before he could calm her.

He knew he couldn’t justify his position, based as it was on complete inequality.

One evening, before she discovered his correspondence with Sabina, they had gone to a bar with some friends to celebrate Tereza’s new job. She was still at the weekly but had left the darkroom to become a staff photographer. Because Tomas had never been much for dancing, one of his younger colleagues took over. He and Tereza made a splendid couple on the dance floor, and Tomas found her more beautiful than ever. He looked on in amazement at the precision and deference with which Tereza anticipated her partner’s moves. The dance seemed to him a declaration that her devotion, her ardent desire to satisfy his every whim was not necessarily bound to his person, that she was willing to respond to the call of any man she met. He had no difficulty imagining Tereza and his colleague as lovers. And the ease with which he did so wounded his pride. The realization that he could effortlessly visualize Tereza’s body coupling with any male body put him in a foul mood. Not until late that night, at home, did he admit to her he was jealous.

This absurd jealousy, grounded as it was in mere hypotheses, proved that he considered her fidelity an unconditional postulate of their relationship. How then could he begrudge her her jealousy of his very real mistresses?

6

During the day she tried (though with only partial success) to believe what Tomas told her and to be as cheerful as she had been before. But her jealousy thus tamed by day burst forth all the more savagely in her dreams, each of which ended in a wail he could silence only by waking her.

Her dreams recurred like themes and variations or television series. For example, she repeatedly dreamed of cats jumping at her face and digging their claws into her skin. We need not look far for an interpretation: in Czech slang the word ‘cat’ means a pretty woman. Tereza saw herself threatened by women, all women. All women were potential mistresses for Tomas, and she feared them all.

In another cycle she was being sent to her death. Once when he woke her screaming in terror in the dead of night she told him about it. ‘I was at a large indoor swimming pool. There were about twenty of us. All women. We were naked and had to march around the pool. There was a basket hanging from the ceiling and a man standing in the basket. The man wore a broad-brimmed hat shading his face, but I could see it was you. You kept giving orders. Shouting at us. We had to sing as we marched, sing and do kneebends. If one of us did a bad kneebend, you would shoot her with a pistol and she would fall dead into the pool. Which made everybody laugh and sing even louder. You never took your eyes off us, and the minute we did something wrong, you would shoot. The pool was full of corpses floating just below the surface. And I knew I lacked the strength to do the next kneebend and you were going to shoot me!’

In a third cycle she was dead. Lying in a hearse as big as a furniture van, she was surrounded by dead women. There were so many of them that the back door would not close and several legs dangled out.

‘But I’m not dead!’ Tereza cried. ‘I can still feel!’

‘So can we,’ the corpses laughed.

They laughed the same laugh as the living women who used to tell her cheerfully that it was perfectly normal that one day she would have bad teeth, faulty ovaries, and wrinkles, because all women had bad teeth, faulty ovaries, and wrinkles. Laughing the same laugh, they told her that she was dead and it was perfectly all right!

Suddenly she felt a need to urinate. ‘You see,’ she cried. ‘I need to pee. That’s proof positive I’m not dead!’

But all they did was laugh again. ‘Needing to pee is perfectly normal! You’ll go on feeling that kind of thing for a long time yet. Like a person who has an arm cut off and keeps feeling it’s there. We may not have a drop of pee left in us, but we keep needing to pee.’

Tereza huddled up against Tomas in bed. ‘And the way they talked to me! Like old friends, people who’d known me for ever. I was appalled at the thought of having to stay with them for ever.’

7

To assuage Tereza’s sufferings, he married her (they could finally give up the room, which she had not lived in for quite some time) and gave her a puppy. It was born to a Saint Bernard owned by a colleague. The sire was a neighbour’s German shepherd.

They tried to come up with a name for it. Tomas wanted the name to be a clear indication that the dog was Tereza’s, and he thought of the book she was clutching under her arm when she arrived unannounced in Prague. He suggested they call the puppy Tolstoy.

‘It can’t be Tolstoy,’ Tereza objected. ‘It’s a girl. How about Anna Karenina?’

‘It can’t be Anna Karenina,’ said Tomas. ‘No woman could possibly have so funny a face. It’s much more like Karenin. Yes, Anna’s husband. That’s just how I’ve always pictured him.’

‘But won’t calling her Karenin affect her sexuality?’

‘It is entirely possible,’ said Tomas, ‘that a female dog addressed continually by a male name will develop lesbian tendencies.’

Strangely enough, Tomas’s prediction came true. Karenin decided he was in love with Tereza. Tomas was grateful to him for it. He would stroke his head and say, ‘Well done, Karenin! That’s just what I want you for. Since I can’t cope with her by myself, you must help me.’

But even with Karenin’s help he failed to make Tereza happy. He became aware of his failure on approximately the tenth day after his country was occupied by Russian tanks. It was August 1968, and Tomas was receiving daily phone calls from a hospital in Zurich. The director there, a physician who had struck up a friendship with Tomas at an international conference, was worried about him and kept offering him a job.

8

If Tomas rejected the Swiss doctor’s offer without a second thought, it was for Tereza’s sake. He assumed she would not want to leave. She had spent the whole first week of the occupation in a kind of trance almost resembling happiness. After roaming the streets with her camera, she would hand the rolls of film to foreign journalists, who actually fought to get them. Once, when she went too far and took a close-up of an officer pointing his revolver at a crowd of people, they arrested her and kept her overnight at Russian military headquarters. There they threatened to shoot her, but no sooner did they let her go than she was back in the streets with her camera.

That is why Tomas was surprised when on the tenth day of the occupation she said to him, ‘Why is it you don’t want to go to Switzerland?’

‘Why should I?’

‘They could make it hard for you here.’

‘They can make it hard for anybody,’ replied Tomas with a wave of the hand. ‘What about you? Could you live abroad?’

‘Why not?’

‘You’ve been out there risking your life for this country. How can you be so nonchalant about leaving it?’

‘Now that Dubcek is back, things have changed.’

It was true: the general euphoria lasted no longer than the first week. A number of official Czech representatives had been dragged away by the Russian army like criminals; no one knew where they were; everyone feared for the men’s lives, and hatred for the Russians drugged the populace like alcohol. It was a drunken carnival of hate.

Czech towns were decorated with thousands of handpainted posters bearing ironic texts, epigrams, poems, and cartoons of Brezhnev and his soldiers – jeered at by one and all as a circus of illiterates. But no carnival can go on for ever. In the meantime the Russians had forced the Czech representatives to sign a compromise agreement in Moscow. When Dubcek returned with them to Prague, he gave a speech over the radio. He was so devastated after his six-day imprisonment he could hardly talk; he kept stuttering and gasping for breath, making long pauses between sentences, pauses lasting nearly thirty seconds.

The compromise saved the country from the worst: the executions and mass deportations to Siberia that had everyone terrified. But one thing was clear: the country would have to bow to the conqueror, stutter, stammer, gasp for air like Alexander Dubcek. The carnival was over. In its wake came workaday humiliation.

Even though Tereza had lived through the events with Tomas and he knew her reaction to be valid, he also knew beneath that reaction was another, more basic reason why she wanted to leave Prague: she had never really been happy before.

The days she walked through the streets of Prague taking pictures of Russian soldiers and looking danger in the face were the best days of her life. They were the only days when the television series of her dreams had been interrupted and she had enjoyed a few happy nights. The Russians had brought equilibrium in their tanks, and now that the carnival was over, she feared her nights again and wanted to escape them. She now knew there were conditions under which she could feel strong and fulfilled, and she longed to go off into the world and seek those conditions somewhere else.

‘It doesn’t bother you that Sabina has emigrated to Switzerland, too?’ Tomas asked.

‘Geneva isn’t Zurich,’ said Tereza. ‘She’ll be much less of a difficulty there than she was in Prague.’

A person who longs to leave the place where he lives is an unhappy person. That is why Tomas accepted Tereza’s desire to emigrate as the culprit accepts his sentence, and why one day, as part of that sentence, he and Tereza and Karenin found themselves in the largest city of Switzerland.

9

He bought a bed for their empty flat (they had no money yet for other furniture) and threw himself into his work with the frenzy of a man of forty beginning a new life.

He made several telephone calls to Geneva. A show of Sabina’s work had opened by chance eight days after the Russian invasion, and in a wave of sympathy for her tiny country, Geneva’s patrons of the arts bought up all her paintings. ‘Thanks to the Russians I’m a rich woman,’ she laughed into the telephone. She invited Tomas to come and see her new studio, and assured him it did not differ greatly from the one he had known in Prague.

He would have been only too glad to visit her, but was unable to find an excuse to explain his absence to Tereza. And so Sabina came to Zurich. She stayed at a hotel. Tomas went to see her after work. He phoned first from the reception desk, then went upstairs. When she opened the door, she stood before him on her beautiful long legs wearing nothing but panties and bra. And a black bowler hat. She stood there staring at him, mute and motionless. Tomas did the same. Suddenly he realized how touched he was. He removed the bowler from her head and placed it on the bedside table. Then they made love without saying a word.

Leaving the hotel for his Zurich abode (which had long since acquired table, chairs, couch, and carpet), he thought happily that he carried his way of living with him as a snail carries his house. Tereza and Sabina represented the two poles of his life, distant and irreconcilable, yet equally vital to it. But the fact that he carried like a part of his body everything he felt was vital to his life meant that Tereza’s dreams continued.

They had been in Zurich for six or seven months when he came home late one evening to find a letter on the table. It told him she had left for Prague. She had left because she lacked the strength to live abroad. She knew she was supposed to bolster him up, but did not know how to go about it. She had been silly enough to think that going abroad would change her. She thought that after what she had been through during the invasion she would stop being petty and grow up, grow wise and strong, but she had overestimated herself. She was weighing him down and would do so no longer. She had drawn the necessary conclusions before it was too late. And she apologized for taking Karenin with her.

He took some sleeping pills but did not close his eyes until morning. Luckily it was Saturday and he could stay at home. For the hundred and fiftieth time he went over the facts: the borders between his country and the rest of the world were no longer open. No telegrams or telephone calls could bring her back. The authorities would never let her travel abroad. Her departure was staggeringly definitive.

10

The realization that he was utterly powerless was like the blow of a sledgehammer, yet it was curiously calming as well. No one was forcing him into a decision. He felt no need to stare at the walls of the houses across the courtyard and ponder whether to live with her or not. Tereza had made the decision herself.

He went to a restaurant to have lunch. He was depressed, but as he ate, his original sense of desperation began to dissipate, lose its edge, and soon all that was left was melancholy. Looking back on the years he had spent with her, he came to feel that their story could have had no better ending. If someone had invented the story, this is how he would have had to end it. One day Tereza came to him uninvited. One day she left the same way. She came with a heavy suitcase. She left with a heavy suitcase.

He paid the bill, left the restaurant, and started walking through the streets, his melancholy growing more and more beautiful. The seven years he had lived with Tereza were, he realized, more attractive in retrospect than in reality.

His love for Tereza was beautiful, but it was also tiring: he had constantly had to hide things from her, sham, dissemble, make amends, buck her up, calm her down, give her evidence of his feelings, play the defendant to her jealousy, her suffering, and her dreams, feel guilty, make excuses and apologies. Now what had been so exhausting had disappeared and only the beauty remained.

Saturday found him for the first time strolling alone through Zurich, breathing in the heady smell of freedom. New adventures hid round each corner. The future was a secret again. He was on his way back to the bachelor life, the life he had once felt destined for, the life that would let him be what he actually was.

For seven years he had lived bound to her, his every step subject to her scrutiny. She might as well have chained iron balls to his ankles. Suddenly his step was much lighter. He soared. He was enjoying the sweet lightness of being.

(Did he feel like phoning Sabina in Geneva? Contacting one or another of the women he had met during his several months in Zurich? No, not in the least. Perhaps he sensed that any woman would make his memory of Tereza unbearably painful.)

11

This curious melancholic fascination lasted until Sunday evening. On Monday everything changed. Tereza forced her way into his thoughts: he imagined her sitting there writing her farewell letter; he felt her hands trembling; he saw her lugging her heavy suitcase in one hand and leading Karenin on his leash with the other; he pictured her unlocking their Prague flat, suffered the utter sense of abandonment breathing her in the face as she opened the door.

During those two beautiful days of melancholy his compassion had taken a holiday. It had slept the sound Sunday sleep of a miner who, after a hard week’s work, needed to gather strength for his Monday shift.

On Saturday and Sunday he felt the sweet lightness of being. On Monday he was hit by a weight the like of which he had never known. The tons of steel in the Russian tanks were nothing compared to it. For there is nothing heavier than compassion. Not even one’s own pain weighs so heavy as the pain one suffers with someone and for someone – a pain intensifed by the imagination and prolonged by a hundred echoes.

He kept warning himself not to give in to compassion, and compassion listened with bowed head and a seemingly guilty conscience. Compassion knew it was being presumptuous, yet it quietly stood its ground, and on the fifth day after her departure Tomas informed the director of his hospital (the man who had phoned him daily in Prague after the Russian invasion) that he had to return at once. He was ashamed. He knew that the move would appear irresponsible, inexcusable to the man. He had a good mind to unbosom himself and tell him the story of Tereza and the letter she had left on the table for him. But in the end he did not.

The head of the hospital was in fact offended.

Tomas shrugged his shoulders and said, ‘Es muss sein. Es muss sein.‘

It was an allusion. The last movement of Beethoven’s last quartet is based on the following two motifs: ‘muss es sein? es muss sein! Es muss sein!’

To make the meaning of the words absolutely clear, Beethoven introduced the movement with the phrase ‘Der schwer gefasste Entschluss,’ which is commonly translated as ‘the difficult resolution.’

This allusion to Beethoven was actually Tomas’s first step back to Tereza, because she was the one who had induced him to buy records of the Beethoven quartets and sonatas.

The allusion was even more pertinent than he had thought, because the Swiss doctor was a great music lover. Smiling serenely, he asked, in the melody of Beethoven’s motif, ‘Muss es sein?’

‘Ja, es muss sein,’ Tomas said again.

12

I can just picture Tomas approaching the Swiss border and a sullen, shock-headed Beethoven conducting the local fire brigade in a rousing farewell-to-emigration brass-band arrangement of the Es Muss Sein March.

But then Tomas crossed the Czech border and was welcomed by columns of Russian tanks. He had to stop his car and wait a half hour before they passed. A ghastly soldier in black, the leader of the tank brigade, stood at the crossroads directing traffic as if every road in the country belonged to him and him alone.

‘Es muss sein!’ was Tomas’s first reaction, but then he began to doubt. Did it really have to be?

Yes, it was unbearable for him to stay in Zurich imagining Tereza living on her own in Prague.

But how long would he have been tortured by compassion? All his life? Or all year? Or a month? Or only a week?

How could he have known? How could he have gauged it?

Any schoolboy can do experiments in the physics laboratory to test the validity of one or another scientific hypothesis. But man, because he has only one life to live, cannot verify a hypothesis by experiment and so can never know for sure whether to follow his passion (compassion) or not.

It was with these thoughts in mind that he opened the door to his flat. Karenin made the homecoming easier by jumping up on him and licking his face. The desire to fall into Tereza’s arms (he could still feel it getting into his car in Zurich) had completely disintegrated. He fancied himself standing opposite her in the midst of a snowy plain, the two of them shivering from the cold.

13

From the very beginning of the occupation Russian military planes flew over Prague all night long. No longer accustomed to the noise, Tomas was unable to fall asleep.

Twisting and turning beside the slumbering Tereza, he recalled something she had once told him a long time before in the course of an insignificant conversation. They had been talking about his friend Z. when she announced, ‘If I hadn’t met you, I’d certainly have fallen in love with him.’

Even then her words had left Tomas in a strange state of melancholy, and now he realized it was only a matter of chance that Tereza loved him and not his friend Z. Apart from her consummated love for Tomas, there was an infinite number of unconsummated loves for other men in the realm of possibility.

We all reject out of hand the idea that the love of our life may be something light, weightless; we presume our love was meant to be, that without it our life would no longer be the same; we feel that Beethoven himself, gloomy and awe-inspiring, is playing the ‘Es muss sein!’ to our own great love.

Tomas often thought of Tereza’s remark about his friend Z. and came to the conclusion that the love story of his life exemplified not ‘Es muss sein!’, it must be so, but rather ‘Es könnte auch anders sein’: it could as well be otherwise.

Seven years earlier, a complex neurological case happened to have been discovered at the hospital in Tereza’s town. They called in the chief surgeon of Tomas’s hospital in Prague for consultation, but the chief surgeon of Tomas’s hospital happened to be suffering from sciatica, and since he was unable to travel he sent Tomas to the provincial hospital instead. The town had several hotels, but Tomas happened to be given a room in the one where Tereza was employed. He happened to have had enough free time before his train left to stop at the hotel restaurant. Tereza happened to be on duty, and happened to be serving Tomas’s table. It had taken six chance happenings to push Tomas towards Tereza, as if he had little inclination to go to her on his own.

He had gone back to Prague because of her. So fateful a decision resting on so fortuitous a love, a love that would not even have existed had it not been for his boss’s sciatica seven years earlier. And that woman, that personification of absolute fortuity, now again lay asleep beside him, breathing deeply.

It was late at night. His stomach started acting up as it tended to do in times of psychic stress.

Once or twice her breath turned into mild snores. Tomas felt no compassion. All he felt was the pressure in his stomach and the despair of having returned.

14

After Tomas had returned to Prague from Zurich, he began to feel uneasy at the thought that his acquaintance with Tereza was the result of six improbable fortuities.

But is not an event in fact more significant and noteworthy the greater the number of fortuities necessary to bring it about?

Chance and chance alone has a message for us. Everything that occurs out of necessity, everything expected, repeated day in and day out, is mute. Only chance can speak to us. We read its message much as gypsies read the images made by tea leaves in the bottom of a cup.

Tomas appeared to Tereza in her restaurant as chance in the absolute. There he sat, poring over an open book, when suddenly he raised his eyes to her, smiled, and said, ‘A cognac, please.’

At that moment, the radio happened to be playing music. On her way back to the counter to pour the cognac, Tereza turned the volume up. She recognized Beethoven. She had known his music from the time a string quartet from Prague had visited their town. Tereza (who, as we know, yearned for ‘something higher’) went to the concert. The hall was nearly empty. The only other people in the audience were the local chemist and his wife. And although the quartet of musicians on stage faced only a trio of spectators down below, they were kind enough not to cancel the concert, giving them a private performance of the last three Beethoven quartets.

Then the chemist invited the musicians to dinner and asked the girl in the audience to go along with them. From then on, Beethoven became her image of the world on the other side, the world she yearned for. Rounding the counter with Tomas’s cognac, she tried to read chance’s message: How was it possible that at the very moment she was taking an order of cognac to a stranger she found attractive, at that very moment she heard Beethoven?

Necessity knows no magic formulae; they are all left to chance. If a love is to be unforgettable, fortuities must immediately start fluttering down to it like birds to Francis of Assisi’s shoulder.

15

He called her back to pay for the cognac. He closed his book (the emblem of the secret brotherhood), and she thought of asking him what he was reading.

‘Can you have it charged to my room?’ he asked.

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘What number are you in?’

He showed her his key, which was attached to a piece of wood with a red six drawn on it.

‘That’s odd,’ she said. ‘Six.’

‘What’s so odd about that?’ he asked.

She had remembered that the house in Prague they had lived in before her parents were divorced was number six. But she answered something else (which we may credit to her wiles): ‘You’re in room six and my shift ends at six.’

‘Well, my train leaves at seven,’ said the stranger.

She did not know how to respond, so she gave him the bill for his signature and took it over to the reception desk. When she finished work, the stranger was no longer at his table. Had he understood her discreet message? She left the restaurant in a state of excitement.

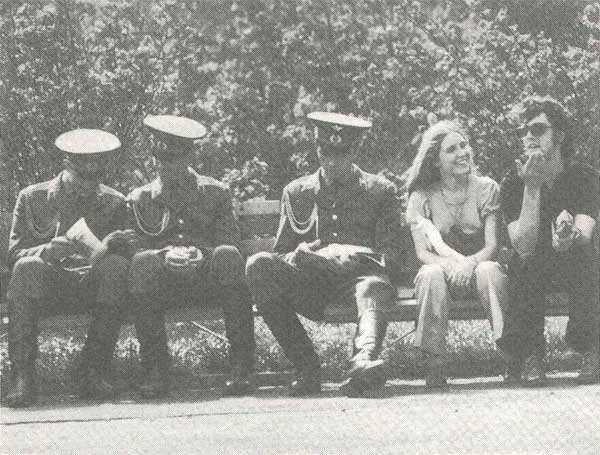

Opposite the hotel was a barren little park, as wretched as only the park of a dirty little town can be, but for Tereza it had always been an island of beauty: it had grass, four poplars, benches, a weeping willow, and a few forsythia bushes.

He was sitting on a yellow bench that afforded a clear view of the restaurant entrance. The very same bench she had sat on the day before with a book in her lap! She knew then (the birds of fortuity had begun alighting on her shoulders) that this stranger was her fate. He called out to her, invited her to sit next to him. (The crew of her soul rushed up to the deck of her body.) Then she walked him to the station, and he gave her his card as a farewell gesture. ‘If ever you should happen to come to Prague…’

16

Much more than the card he slipped her at the last minute, it was the implication of all those fortuities (the book, Beethoven, the number six, the park bench) that gave her the courage to leave home and take her fate into her own hands. It may well be those few fortuities (quite modest, by the way, even drab, just what one would expect from so lacklustre a town) that set her love in motion and provided her with a source of energy she had not yet exhausted at the end of her days.

Our day-to-day life is bombarded with fortuities or, to be more precise, with the accidental meetings of people and events we call coincidences. ‘Coincidence’ means that two events unexpectedly happen at the same time; they meet: Tomas appears in the hotel restaurant at the same time as the radio is playing Beethoven. We do not even notice the great majority of such coincidences. If the seat Tomas occupied had been occupied instead by the local butcher, Tereza never would have noticed that the radio was playing Beethoven (though the meeting of Beethoven and the butcher would also have been an interesting coincidence). But her nascent love inflamed her sense of beauty, and she would never forget that music. Whenever she heard it, she would be touched. Everything going on around her at that moment would bask in the glow of the music and take on its beauty.

Early in the novel that Tereza clutched under her arm when she went to visit Tomas, Anna meets Vronsky in curious circumstances: they are at the railway station when someone is run over by a train. At the end of the novel, Anna throws herself under a train. This symmetrical composition – the same motif appears at the beginning and at the end – may seem quite ‘novelistic’ to you, and I am willing to agree, but only on condition that you refrain from reading such notions as ‘fictive,’ ‘fabricated,’ and ‘untrue to life’ into the word ‘novelistic.’ Because human lives are composed in precisely such a fashion.

They are composed like music. Guided by his sense of beauty, an individual transforms a chance occurrence (Beethoven’s music, a suicide at the railway station) into a motif, which then assumes a permanent place in the composition of the individual’s life. Anna could have chosen another way to take her life. But the motif of death and the railway station, unforgettably bound to the birth of love, enticed her in her hour of despair with its dark beauty. Without realizing it, the individual composes her life according to the laws of beauty even in times of greatest distress.

It is wrong, then, to chide the novel for being fascinated by mysterious coincidences (like the meeting of Anna, Vronsky, the railway station, and death or the meeting of Beethoven, Tomas, Tereza, and the cognac), but it is right to chide man for being blind to such coincidences in his daily life. For he thereby deprives his life of a dimension of beauty.

17

Impelled by the birds of fortuity fluttering down on her shoulders, she took a week’s leave and, without a word to her mother, boarded the train to Prague. During the journey, she made frequent trips to the toilet to look in the mirror and beg her soul not to abandon for a moment the deck of her body on this most crucial day of her life. Scrutinizing herself on one such trip, she had a sudden scare: she felt a scratch in her throat. Could she be coming down with something on this most crucial day of her life?

But there was no turning back. So she phoned him from the station, and the moment he opened the door, her stomach started rumbling terribly. She was mortified. She felt as though she were carrying her mother in her stomach and her mother had guffawed to spoil her meeting with Tomas.

For the first few seconds she was afraid he would throw her out on account of the crude noices she was making, but then he put his arms around her. She was grateful to him for ignoring her rumbles, and kissed him passionately, her eyes misting. Before the first minute was up, they were making love. She screamed while making love. She had a fever by then. She had come down with the flu.

When she travelled to Prague a second time, it was with a heavy suitcase. She had packed all her things, determined never again to return to the small town. He had invited her to come to his place the following evening. That night, she had slept in a cheap hotel. In the morning, she carried her heavy suitcase to the station, left it there, and roamed the streets of Prague the whole day with Anna Karenina under her arm. Not even after she rang the doorbell and he opened the door would she part with it. It was like a ticket into Tomas’s world. She realized she had nothing but that miserable ticket and the thought brought her nearly to tears. To keep from crying, she talked non-stop in a raucous voice; and she laughed. And again he took her in his arms almost at once and they made love. She had entered a mist in which nothing could be seen and only her scream could be heard.

18

It was no sigh, no moan; it was a real scream. She screamed so hard that Tomas had to turn his head away from her face, afraid that her voice so close to his ear would rupture his eardrum. The scream was not an expression of sensuality. Sensuality is the total mobilization of the senses: an individual observes his or her partner intently, straining to catch every sound. But her scream aimed at crippling the senses, preventing all seeing and hearing. What was screaming in fact was the naive idealism of her love trying to banish all contradictions, banish the duality of body and soul, banish perhaps even time.

Were her eyes closed? No, but they were not looking anywhere. She kept them fixed on the void of the ceiling. At times she twisted her head violently from side to side.

When the scream died down, she fell asleep at his side, clutching his hand. She held his hand all night.

Even at the age of eight she would fall asleep by pressing one hand into the other and making believe she was holding the hand of the man whom she loved, the man of her life. So if in her sleep she pressed Tomas’s hand with tenacity, we can understand why: she had been training for it since childhood.

19

‘I want to make love to you in my studio. It will be like a stage surrounded by people. The audience won’t be allowed up close, but they won’t be able to take their eyes off us…’

As time passed, the image lost some of its original cruelty and began to excite Tereza. She started whispering the details to him while they made love.

Then it occurred to her that there might be a way to avoid the condemnation she saw in Tomas’s infidelities: all he had to do was take her along, take her with him when he went to see his mistresses!

Maybe then her body would again become the first and only among all the others. Her body would become his second, his assistant, his alter ego. ‘I’ll undress them for you, give them a bath, bring them in to you,’ she would whisper to him as they pressed together. She yearned for the two of them to merge into a hermaphrodite. Then the other women’s bodies would be their playthings.

20

Oh, to be the alter ego of his polygamous life! Tomas refused to understand, but she could not get it out of her head, and tried to cultivate her friendship with Sabina. Tereza began by offering to do a series of photographs of her, portraits.

Sabina invited her to her studio, and at last she saw the spacious room and its centrepiece: the large, square, platform-like bed.

‘I feel awful you’ve never been here before’, said Sabina, as she showed her the pictures leaning against the wall. She even pulled out an old canvas, an ironworks under construction, which she had done during her schooldays, a period when the strictest realism had been required of all students (art that was not realistic was said to sap the foundations of socialism). In the spirit of the wager she had tried to be stricter than her teachers and had painted in a style concealing the brush strokes and closely resembling colour photography.

Next to the bed stood a small table, and on the table the model of a human head, the kind hairdressers put wigs on. Sabina’s wig-stand sported a bowler hat rather than a wig. ‘It used to belong to my grandfather,’ she said with a smile.

It was the kind of hat – black, hard, round – that Tereza had seen only on the screen, the kind of hat Chaplin wore. She smiled back, picked it up, and after studying it for a time, said, ‘Would you like me to take your picture in it?’

Sabina laughed for a long time at the idea. Tereza put down the bowler hat, picked up her camera, and starting taking pictures.

When she had been at it for almost an hour, she suddenly said, ‘What would you say to some nude shots?’

‘Nude shots?’ Sabina laughed.

‘Yes’, said Tereza, repeating her proposal more boldly, ‘nude shots.’

‘That calls for a drink’, said Sabina, and opened a bottle of wine.

Tereza felt her body going weak; she was suddenly tongue-tied. Sabina, meanwhile, strode back and forth, wine in hand, going on about her grandfather, who’d been the mayor of a small town; Sabina had never known him; all he’d left behind was this bowler hat and a picture showing a raised platform with several small-town dignitaries on it; one of them was Grandfather; it wasn’t at all clear what they were doing up there on the platform; maybe they were officiating at some ceremony, unveiling a monument to a fellow dignitary who had also once worn a bowler hat at public ceremonies.

Sabina went on and on about the bowler hat and her grandfather until, emptying her third glass, she said, ‘I’ll be right back’ and disappeared into the bathroom.

She came out in her bathrobe. Tereza picked up her camera and put it to her eye. Sabina threw open the robe.

21

The camera served Tereza as both a mechanical eye through which to observe Tomas’s mistress and a veil by which to conceal her face from her.

It took Sabina some time before she could bring herself to slip out of the robe entirely. The situation she found herself in was proving a bit more difficult than she had expected. After several minutes of posing, she went up to Tereza and said, ‘Now it’s my turn to take your picture. Strip.’

Sabina had heard the command ‘Strip!’ so many times from Tomas that it was engraved in her memory. And so, Tomas’s mistress had just given Tomas’s command to Tomas’s wife. The two women were joined by the same magic word. That was Tomas’s way of unexpectedly turning an innocent conversation with a woman into an erotic situation. Instead of stroking, flattering, pleading, he would issue a command, issue it abruptly, unexpectedly, softly yet firmly and authoritatively, and at a distance: at such moments he never touched the woman he was addressing. He often used it on Tereza as well, and even though he said it softly, even though he whispered it, it was a command, and obeying never failed to arouse her. Hearing the word now made her desire to obey even stronger, because doing a stranger’s bidding is a special madness, a madness all the more heady in this case because the command came not from a man but from a woman.

Sabina took the camera away from her, and Tereza took off her clothes. There she stood before Sabina naked and disarmed. Literally disarmed: deprived of the apparatus she had been using to cover her face, and aim at Sabina like a weapon. She was completely at the mercy of Tomas’s mistress. This beautiful submission intoxicated Tereza. She wished that the moments she stood naked opposite Sabina would never end.

I imagine that Sabina, too, felt the strange enchantment of the situation: her lover’s wife standing oddly compliant and timorous before her. But after clicking the shutter two or three times, almost frightened by the enchantment and eager to dispel it, she burst into loud laughter.

Tereza followed suit, and the two of them got dressed.

22

All previous crimes of the Russian empire had been committed under the cover of a discreet shadow. The deportation of a million Lithuanians, the murder of hundreds of thousands of Poles, the liquidation of the Crimean Tatars remain in our memory, but no photographic documentation exists; sooner or later they will therefore be proclaimed as mystifications. Not so the 1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia, of which both stills and motion pictures are kept in archives throughout the world.

Czech photographers and cameramen were acutely aware that they were the ones who could best do the only thing left to do: preserve the face of violence for the distant future. Seven days in a row, Tereza roamed the streets, photographing Russian soldiers and officers in compromising situations. The Russians did not know what to do. They had been carefully briefed about how to behave if someone fired at them or threw stones, but they had received no directives about what to do when someone aimed a lens.

She shot roll after roll and handed about half of them, undeveloped, to foreign journalists (the borders were still open, and reporters passing through were grateful for any kind of document). Many of her photographs turned up in the Western press. They were pictures of tanks, of threatening fists, of houses destroyed, of corpses covered with bloodstained red-white-and-blue Czech flags, of young men on motorcycles racing full speed around the tanks and waving Czech flags on long staffs, of young girls in unbelievably short skirts provoking the miserable sexually-famished Russian soldiers by kissing random passers-by before their eyes. As I have said, the Russian invasion was not only a tragedy; it was a carnival of hate filled with a curious (and no longer explicable) euphoria.

23

She took some fifty prints with her to Switzerland, prints she had made herself with all the care and skill she could muster. She offered them to a high-circulation illustrated magazine. The editor gave her a kind reception (all Czechs still wore the halo of their misfortune, and the good Swiss were touched); he offered her a seat, looked through the prints, praised them, and explained that because a certain time had elapsed since the events, they hadn’t the slightest chance (‘not that they aren’t very beautiful!’) of being published.

‘But it’s not over yet in Prague!’ she protested, and tried to explain to him in her bad German that at this very moment, even with the country occupied, with everything against them, workers’ councils were forming in the factories, the students were going out on strike demanding the departure of the Russians, and the whole country was saying aloud what it thought. ‘That’s what’s so unbelievable! And nobody here cares any more.’

The editor was glad when an energetic woman came into the office, and interrupted the conversation. The woman handed him a folder and said, ‘Here’s the nudist beach article.’

The editor was delicate enough to fear that a Czech who photographed tanks would find pictures of naked people on a beach frivolous. He laid the folder at the far end of the desk and quickly said to the woman, ‘How would you like to meet a Czech colleague of yours? She’s brought me some marvellous pictures.’

The woman shook Tereza’s hand and picked up her photographs. ‘Have a look at mine in the meantime,’ she said.

Tereza leaned over to the folder and took out the pictures.

Almost apologetically, the editor said to Tereza, ‘Of course they’re completely different from your pictures.’

‘Not at all,’ said Tereza. ‘They’re the same.’

Neither the editor nor the photographer understood her, and even I find it difficult to explain what she had in mind when she compared a nude beach to the Russian invasion. Looking through the pictures, she stopped for a time at one that showed a family of four standing in a circle: a naked mother leaning over her children, her giant tits hanging low like a goat’s or cow’s, and the husband leaning the same way on the other side, his penis and scrotum also looking very much like an udder, in miniature.

‘You don’t like them, do you?’ asked the editor.

‘They’re good photographs.’

‘She’s shocked by the subject matter,’ said the woman. ‘I can tell just by looking at you that you’ve never set foot on a nude beach.’

‘No,’ said Tereza.

The editor smiled. ‘You see how easy it is to guess where you’re from? The Communist countries are awfully puritanical.’

‘There’s nothing wrong with the naked body,’ the woman said, with maternal affection. ‘It’s normal. And everything normal is beautiful!’

24

The woman photographer invited Tereza to the magazine’s cafeteria for a cup of coffee. ‘Those pictures of yours, they’re very interesting. I couldn’t help noticing what a terrific sense of the female body you have. You know what I mean. The girls with the provocative poses!’

‘The ones kissing passers-by in front of the Russian tanks?’

‘Yes. You’d be a top-notch fashion photographer, you know? You’d have to get yourself a model first, someone like you who’s looking for a break. Then you could make a portfolio of photographs and show them to the agencies. It would take some time before you made a name for yourself, naturally, but I can do one thing for you here and now: introduce you to the editor in charge of our garden section. He might need some shots of cactuses and roses and things.’

‘Thank you very much,’ Tereza said sincerely, because it was clear that the woman sitting opposite her was full of good will.

But then she said to herself, Why take pictures of cactuses? She had no desire to go through in Zurich what she’d been through in Prague: battles over job and career, over every picture published. She had never been ambitious out of vanity. All she had ever wanted was to escape from her mother’s world. Yes, she saw it with absolute clarity: no matter how enthusiastic she was about taking pictures, she could just as easily have turned her enthusiasm to any other endeavour. Photography was nothing but a way of getting at ‘something higher’ and living beside Tomas.

She said, ‘My husband is a doctor. He can support me. I don’t need to take pictures.’

The woman photographer replied, ‘I don’t see how you can give it up after the beautiful work you’ve done.’

Yes, the pictures of the invasion were something else again. She had not done them for Thomas. She had done them out of passion. But not passion for photography. She had done them out of passionate hatred. The situation would never recur. And these photographs, which she had made out of passion, were the ones nobody wanted because they were out of date. Only cactuses had perennial appeal. And cactuses were of no interest to her.

She said, ‘You’re too kind, really, but I’d rather stay at home. I don’t need a job.’

The woman said, ‘But will you be fulfilled sitting at home?’

Tereza said, ‘More fulfilled than by taking pictures of cactuses.’

The woman said, ‘Even if you take pictures of cactuses, you’re leading your life. If you live only for your husband, you have no life of your own.’

All of a sudden Tereza felt annoyed: ‘My husband is my life, not cactuses.’

The woman photographer responded in kind: ‘You mean you think of yourself as happy?’

Tereza, still annoyed, said, ‘Of course I’m happy!’

The woman said, ‘The only kind of woman who can say that is very…’ She stopped short.

Tereza finished it for her: ‘…limited. That’s what you mean, isn’t it?’

The woman regained control of herself and said, ‘Not limited. Anachronistic.’

‘You’re right,’ said Tereza wistfully. ‘That’s just what my husband says about me.’

25

She was at home alone. Tomas spent days on end at the hospital. At least she had Karenin and could take him on long walks. Home again, she would pore over her German and French grammars. But she felt sad and had trouble concentrating. She kept coming back to the speech Dubcek had given over the radio after his return from Moscow. Although she had completely forgotten what he said, she could still hear his quivering voice. She thought about how foreign soldiers had arrested him, the head of an independent state, in his own country, held him for four days somewhere in the Ukrainian mountains, informed him he was to be shot – as, twelve years before, they had shot his Hungarian predecessor Imre Nagy – then packed him off to Moscow, ordered him to have a bath and shave, to change his clothes and put on a tie, apprised him of the decision to commute his execution, instructed him to consider himself head of state once more, sat him at a table opposite Brezhnev, and forced him to act.

He returned, humiliated, to address his humiliated nation. He was so humiliated he could not even speak. Tereza would never forget those awful pauses in the middle of his sentences. Was he that exhausted? Ill? Had they drugged him? Or was it only despair? If nothing was to remain of Dubcek, then at least those awful long pauses when he seemed unable to breathe, gasping for air before a whole nation glued to its radios, at least those pauses would remain. Those pauses contained all the horror that had descended on their country.

It was the seventh day of the invasion. She heard the speech in the editorial offices of a newspaper that had been transformed overnight into an organ of the resistance. Everyone present hated Dubcek at that moment. They reproached him for compromising; they felt humiliated by his humiliation; his weakness offended them.

Thinking back to those days, she no longer felt any aversion to the man. The word ‘weak’ no longer sounded like a verdict. Any man confronted with superior strength is weak, even a man of Dubcek’s athletic build. The very weakness that had seemed unbearable, repulsive, to them at the time, the weakness that had driven Tereza and Tomas from the country, suddenly attracted her. She realized that she too belonged among the weak, in the camp of the weak, in the country of the weak, and that because they were weak and gasped for air in the middle of a sentence she owed them her allegiance.

She felt attracted by this weakness as by vertigo. She felt attracted by it because she felt weak herself. Again she began to feel jealous and again her hands shook. When Tomas noticed it, he did what he usually did: he took her hands in his and tried to calm them by pressing hard. She tore them away from him.

‘What’s the matter?’ he asked.

‘Nothing.’

‘What do you want me to do for you?’

‘I want you to be old. Ten years older. Twenty years older!’

What she meant was: I want you to be weak. As weak as I am.

26

Karenin was not overjoyed by the move to Switzerland. Karenin hated change. Dog time cannot be plotted along a straight line; it does not move on and on, from one thing to the next. It moves in a circle like the hands of a clock, turning round and round day in and day out following the same path. In Prague, when Tomas and Tereza bought a new chair or moved a flower pot, Karenin would look on in displeasure. It disturbed his sense of time. It was as though they were trying to dupe the hands of the clock by changing the numbers on its face.

He was the timepiece of their lives. One day when they came back from a walk, the phone was ringing. She picked up the receiver.

It was a woman’s voice speaking German and asking for Tomas. It was an impatient voice, and Tereza felt it had a ring of derision to it. When she said that Tomas wasn’t there and she didn’t know when he’d be back, the woman on the other end of the line started laughing. Then she hung up without saying goodbye.

Tereza knew it did not mean a thing. It could have been a nurse from the hospital, a patient, a secretary, anyone. But still she was upset and was unable to concentrate on anything. It was then she realized she had lost the last bit of strength she had had at home: she was absolutely incapable of tolerating this absolutely insignificant incident.

Being in a foreign country means walking a tightrope high above the ground without the net you have in your homeland – the net of family, colleagues, friends and where you can easily say what you have to say in a language you have known from childhoood. In Prague she was dependent on Tomas only when it came to the heart; here she was dependent on him for everything. What would happen to her here if he abandoned her? Would she have to live her whole life in fear of losing him?

She told herself: their acquaintance had been based on a fallacy from the start. The copy of Anna Karenina under her arm amounted to false papers; it had given Tomas the wrong idea. In spite of their love, they had made each other’s life a hell. The fact that they loved each other was merely proof that the fault lay not in themselves, in their behaviour or any inconstancy of feeling, but rather in their incompatibility, because he was strong and she was weak. She was like Dubcek, who made a thirty-second pause in the middle of a sentence; she was like her country, which stuttered, gasped for breath, could not speak.

But when the strong were too weak to hurt the weak, the weak had to be strong enough to leave.

And having told herself all this, she pressed her face against Karenin’s furry head and said, ‘Sorry, Karenin. It looks as though you’re going to have to move again.’

27

Sitting crushed into a corner of the train compartment with her heavy suitcase above her head and Karenin squeezed against her legs, she kept thinking about the cook at the hotel restaurant where she had worked when she lived with her mother. The cook would take every opportunity to give her a slap on the behind, and never tired of asking her in front of everyone when she would give in and go to bed with him. It was odd that he was the one who came to mind. He had always been the prime example of everything she loathed. And now all she could think of was looking him up and telling him, ‘You used to say you wanted to sleep with me. Well, here I am.’

She longed to do something drastic, burn her boats. She longed to enact the brutal destruction of the past seven years of her life. It was vertigo. A heady, insuperable longing to fall.

We might also call vertigo the intoxication of the weak. Aware of his weakness, a man decides to give in rather than stand up to it. He is drunk with weakness, wishes to grow even weaker, wishes to fall down in the middle of the main square, in front of everybody, wishes to be down, lower than down.

She tried to talk herself into settling outside Prague and giving up her profession as a photographer. She would go back to the small town from which Tomas’s voice had once lured her.

But once in Prague, she found she had to spend some time taking care of various practical matters, and began putting off her departure.

On the fifth day, Tomas suddenly turned up. Karenin jumped all over him, so it was a while before they had to make any overtures to each other.

They felt they were standing on a snow-covered plain, shivering with cold.

Then they moved together like lovers who had never kissed before.

‘Has everything been all right?’ he asked.

‘Yes,’ she answered.

‘Have you been to the magazine?’

‘I’ve given them a call.’

‘Well?’

‘Nothing yet. I’ve been waiting.’

‘For what?’

She made no response. She could not tell him she had been waiting for him.

28

Now we return to a moment we already know about. Tomas was desperately unhappy and had a bad stomach ache. He did not fall asleep until very late at night.

Soon thereafter Tereza awoke. (There were Russian airplanes circling over Prague, and it was impossible to sleep for the noise.) Her first thought was that he had come back because of her. Because of her, he had changed his destiny. Now he would no longer be responsible for her: now she was responsible for him.

The responsibility, she felt, seemed to require more strength than she could muster.

But all at once she recalled that just before he had appeared at the door of their flat the day before, the church bells had chimed six o’clock. On the day they first met, her shift had ended at six. She saw him sitting there in front of her on the yellow bench and heard the bells in the belfry chime six.

No, it was not superstition. It was a sense of beauty that cured her of her depression and imbued her with a new will to live. The birds of fortuity had alighted once more on her shoulders. There were tears in her eyes, and she was unutterably happy to hear him breathing at her side.

This is an extract from The Unbearable Lightness of Being by Milan Kundera, published in the UK by Faber & Faber.

Photograph by Marc Riboud