I. NEVER

Faizal carries his wife in his pocket: she is a white handkerchief. Faizal carries his three daughters in his other pocket: three small stones gathered from the side of the road. Their names are lost to walking. His sons Mohammed and Rafiq flank him. They carry the memories of their sisters and mother in their silence. Faizal closed down his carpet shop three months ago; he misses his days bargaining at his counter. No one has told Faizal why India has changed – he is not one of those men who drinks tea and talks politics at night. Every time he meets a dead person he asks them what his wife’s name was. He asks and puts his hands in his pockets.

Zoom out and it looks like the whole of India is walking. Walking towards a blue line on a rough map drawn on to a napkin. Mohammed Siddique, my father, is a young man of seventeen years on the road from Jullundur to Lahore. He will never be a Pakistani, he will always be an immigrant – a series of questions which Faizal cannot answer.

The scent of the fields after the rain has stopped for a while. Humidity rising. The earth’s redness in the dusk. Walking towards a blue line on a piece of paper. ‘It will be better when we’re across the border,’ Faizal says.

They move in colour, carrying everything they can. Though the eye of the century sees them in black and white, as a series of stills in a photographer’s portfolio. Partition: sounds like a thin wall made of simple materials between rooms that can easily be taken down. Take the word in your left hand and feel its weight. It is nothing – a few sheets of paper.

II. THE LAST PARTITION

The last time I saw my father was in 1989; it had been thirteen years since we were last together. He always considered himself an Indian. He told me that he would never believe that ‘something pure could be born from blood, or from the politics of people like Jinnah, Gandhi and Mountbatten.’ He walks to the kitchen and I follow him. He cooks a treat of pakoras and we sit to eat them, wearing our coats in his cold house in North Manchester. He tells me that he had finally gone to live in Pakistan, and had married again, but had had no more children. He hands me my inheritance: a box of conversations. Fragments of memory, blank spaces, things which there are no words for. One by one I pick up each item from the box: belonging, land, manliness and family. I turn them over in my hand. I put a handkerchief and three stones into my jacket pocket.

Father is beautifully dressed. He had learned to wear a shirt and a suit early in his life in Britain. Even when he was working in factories, he seemed to have the magical power of keeping his shirt spotless. We sat in that house for three days and talked as much as we could, considering the men we were. He wanted me to be his boy again. I wanted his presence to rely on, a sense of home from him, but how can you ask for that? I was full of my mother’s stories of his abandonment. With more than the table between us, we turned memory like the pages of an old photo album. Then he simply vanished, leaving no address.

III. FOREIGNERS

Mohammed had barely set foot in the new country before his father told him to leave again. Faizal warned him that Pakistan would turn the world upside down. He told his son that he knew of some people who had gone to England to make new lives. Smallpox had left Mohammed with a pockmarked face, but the loss of his mother and sisters, and now more separation, changed something in his brow and in his eyes. Faizal’s plan was that Mohammed would take a job on a merchant ship, and Rafiq would stay in Pakistan. Mohammed would then make his way in the world and support the family by sending money home.

Arriving at London Road station, he breathed his first Manchester air. After the rains of the Punjab, the sea and rust of the ship, he found the Northern air dark and sharp. Taking a taxi he showed the driver a piece of paper with a misspelled address and an unreadable name in blue ink. As he traveled, Mohammed had kept the piece of paper like a holy object folded into the back of a book, which was itself kept in the middle layer of his clothes. The paper unlocked a place to stay and some work. It brought him company and his first Punjabi meal in a long time. Somehow the family he stayed with had managed to get hold of spices and chapatti flour, and using English chicken they made food that tasted of home.

He heard of a good job over at Dexine’s in Rochdale. Dexine’s made rubber fittings for aeroplanes, and among the noise of the hydraulic presses, and the heat and smell of molten rubber, he established himself. He bought his first suit and two white shirts from Greenwood’s tailors, and began to make weekly trips to Manchester or Bradford to buy flour and spices and to have occasional meals with the friends who had helped him.

Each minute leads unimaginably to years. Mohammed worked, became a ladies’ man and bought a house. He was seeing a fiery Northern Irish divorcee by the name of Mary Rooney for a while. They liked each other but he was more interested in her sister Norah, who was petite and very pretty with fine porcelain skin and dark brown hair. It was only natural that he would be drawn to a woman who also came from a divided country. They used to go for drives in his black Morris Minor to have picnics in nearby Yorkshire. Friday nights they would go to the ABC cinema.

They married in 1963. Her Irish ways didn’t fit well into his house: he liked to read the paper, smoke cherry tobacco in his pipe and drink a bottle of Guinness in the evening. She liked to talk; mostly it seemed about the neighbours. They were incapable of making plans and they were hardly able to speak of the landscapes that had made them. They spent a few years having children and not knowing each other. They faced racism whenever they went out: people swore at them, spat at them. ‘A Paki and an Irish woman – disgusting.’ Norah’s own father turned away from her for marrying ‘a foreigner’, and she grew to blame Mohammed.

IV. 1970

The thing I remember most about my father is his absence – he seemed to work all the time. Memories of him from my childhood are like car lights on the ceiling when you are restless at night, catching your attention and keeping you awake, when all you really want is the safety of the darkness.

I remember a time when I was a little boy. We were crossing Yorkshire Street, going to the hardware store to buy a shovel, as he wanted to grow vegetables in the garden. I held his hand as we crossed the road and I felt safe, because I was with the big man, and his love surrounded me.

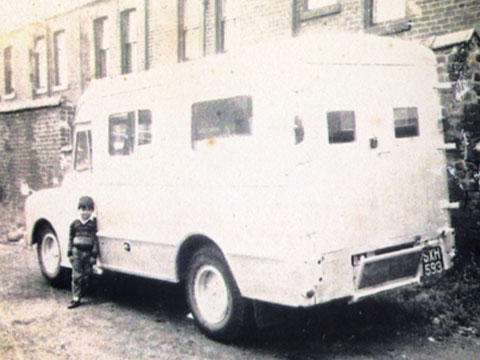

The two other times that I draw on to get a sense of him are the day we ate pakoras with our coats on, and a journey from much earlier. In 1970 he decided to take my mother, my sisters and me to Pakistan to see his father and brother. He bought a second-hand Seddon Diesel minibus for fifty pounds and spent weeks buying food, installing beds and shelves. He bought six fan belts. We left in May and drove overland across Europe and the Middle East. Imagine that journey today: France, Germany, Austria, Bulgaria, Yugoslavia, Turkey, Iran, Iraq and Afghanistan; and finally Pakistan.

I still find myself sitting next to him sometimes, looking forwards through the windscreen of the Seddon, enjoying the vibration from the diesel engine. He had been away for longer than he had lived on the subcontinent. He arrived to find that time had separated him from his Pakistani family. My father had remained an Indian and developed a lot of English ways. Faizal had become the new country. Their father-son bond was broken, even though my father had been sending money home since his first job. They could not look at each other now. Mohammed had written home almost every month without fail, but letters and money count for little compared with actually being together.

To try and make ends meet my father used the minibus as a wedding taxi. My mother was relegated to the back rooms of the house where she had no way of communicating with the other women. Faizal had remarried and brother Rafiq had his own family. Faizal despised the mixed-race children and the white woman his son had brought with him. He thought it was very wrong that Mohammed should have married a non-Muslim. Mohammed’s wedding taxi failed to make money. The journey was the end of my parents’ marriage and my mother decided to leave. My father had had enough of being the outsider in England, of having to do physical work and never being allowed to move up to management. He decided to become an immigrant again. This time he went to Germany, he had heard that there were better jobs and that it was more civilised. The rest of us flew back to the newly decimalised England in the cold January of 1971.

After my parents separated, my father would come to see us every year around Christmas. He would turn up bearing gifts, trying to do the right thing by everyone. He would always bring me a packet of Tunnock’s Caramel Wafers. I would try to make it last for a long time. He managed to keep on with his yearly ritual of visits until I was thirteen; then for some reason his name became something you shouldn’t say out loud. My mother stopped mentioning him, other than to heap blame on him. My sisters and I learned to swallow our tongues.

V. IMAGE PROBLEM

It is raining in Pakistan; aid is insufficient and slow to arrive. Images of hands held out asking for help: the British news has always served up a very particular dish when it comes to showing Pakistan. If my father is still alive, he may be caught up in the floods. Imagine living through Partition, and now this. I have not seen him for nineteen years and I am worried about him. In the past I have tried to find him by putting adverts in Pakistan’s Daily Jang. I sometimes think of going over myself and simply standing on the street and asking for help. I remember running between the cotton rows and eating sugar cane there when I was a boy, but something stops me returning – fear of not finding him, or fear of finding out he is dead.

VI. GIFT

My father never returned to his hometown, so in 2008 I travelled to India – to find the beginning of this story. I needed to place myself in his landscape, and walk in his footsteps. I wanted to return his spirit to the source and undo the Partition. I brought with me the one good photograph I have of my father, taken on my parents’ wedding day. He is smiling, about to climb into the wedding car. His hair is Brylcreemed back, and his suit is perfect.

I decide to go out and lose myself in Jullundur. Finding a backstreet park, I sit down and take his photo from my notebook. Tears come. We are crossing the road to the hardware store, my child’s hand in his hand. We are in the house in Manchester and he is making pakoras. The sun shines down on us and the other people in the park as they carry on with their walks and conversations without paying us any attention.

Image by puppaluppa