Sick of Steel

Gus Palmer & Emilie Harley

Taranto is a town located in the heel of the Italian boot, but despite being in the tourist-loved, turquoise-watered region of Puglia, there is a distinct absence of sun-creamed holidaymakers. What tends to put them off is the sight of the giant steel factory on the horizon, and the stories of polluted seafood and carcinogenic dust in the air.

We spent two weeks in the poor neighbourhood of Tamburi, which sits in the shadow of the Ilva steel plant, one of Europe’s largest, to see what it is to live somewhere that makes you sick.

On our first day we’re greeted by Sylvia Cristofaro, a 21-year-old anti-Ilva activist, who took us on a tour of the streets she grew up in. Tamburi has been home to her family for four generations. She pointed out the reddish glow coming from the pavements and the cars. ‘It’s mineral dust that has blown in from the factory. It’s poison. And it’s what we breathe.’ This dust contains dioxins that cause cancer. Every morning there is a new toxic coating, as if a copper snow has fallen, and residents can be seen sweeping it off their balconies.

That the steel plant is making people sick is impossible to deny, despite the factory owner’s protestations that the emissions are safe. A local doctor gave us the disquieting figures, telling us how the child cancer rate in Taranto is 54 per cent higher than in the rest of the region. Rates of lung cancer are 30 per cent higher.

As we speak to factory employees sitting outside on plastic chairs, enjoying an after-work beer, the risks become clear. A worker named Cataldo shows us photos of pipes leaking dangerous waste inside the plant. He explains that the factory is in financial meltdown and cannot afford any repairs.

Cataldo has begun campaigning for workers to be given proper protective clothing, hoping this might help keep them safe from harmful substances. But ultimately, he and the other workers are all too aware that one day the steel plant might kill them.

As a worker actively pushing for change, Cataldo is something of an anomaly. Everyone we speak to in Tamburi has lost somebody to cancer, yet there is a palpable lack of anger towards the plant, and very few are willing to speak out.

The factory is, after all, the economic lifeblood of Tamburi; no one wants to see it close. This dependency is described by another factory employee, Francesco, who – after telling us that out of the 100 people he works with, 10 have throat cancer – explains that, ‘if one of your sons dies of cancer, Ilva will call and offer your other son a job.’

But there is also an apathy that runs more deeply than the fear of unemployment. Many of the people of Tamburi simply do not care what the steel factory is doing to them. Although it’s difficult to comprehend, Sylvia attempted to explain it to us: ‘Ilva has polluted the minds of the people, and now they believe their lives don’t matter’.

Tamburi is isolated (they speak a dialect that most native Italians cannot understand), ignored and incredibly impoverished – the factory has a hold over this neighbourhood that would be impossible anywhere else.

In this deeply religious community, Ilva donated money to build the church. Above the altar, in a painting of Jesus on the cross, the steel factory can be seen in the background. The message is clear: Ilva is God.

When a plant employee dies, families often do not have enough money to cover the costs of a funeral, and they turn to Ilva. Ilva will pay for the burial, which the majority see as an act of generosity on the factory’s part. We were shown the graveyard full of Ilva employees – the tombstones are cut from amber-coloured stone so that it’s less noticeable when they turn red from the pollution.

But for those who have lost too much because of the steel factory, apathy is impossible. We met Vincenzo Fornaro, who is fighting the factory his own way. Vincenzo used to have a sheep farm but in 2008 dioxins were found in all the animals in the area. Any milk or meat from the livestock would have been unfit for human consumption and the animals had to be slaughtered. 2,517 animals were killed, and Vincenzo himself lost 605 sheep – his whole livelihood. At this point in Vincenzo’s life, his mother had already died of cancer and he had to have his own kidney removed due to cancer. No compensation was received and the farmers were left with nothing.

Most gave up, but Vincenzo looked for solutions. He heard about how after the Chernobyl disaster, locals planted cannabis to remove dioxins from the soil. He decided that he wanted to try it in Taranto. Now, standing proudly in his hemp field, Vincenzo explained that doing this was all about showing Ilva that he wasn’t just going to take it. Soon the hemp will remove the pollution from his land, and in the meantime he is considering whether or not he should run for mayor.

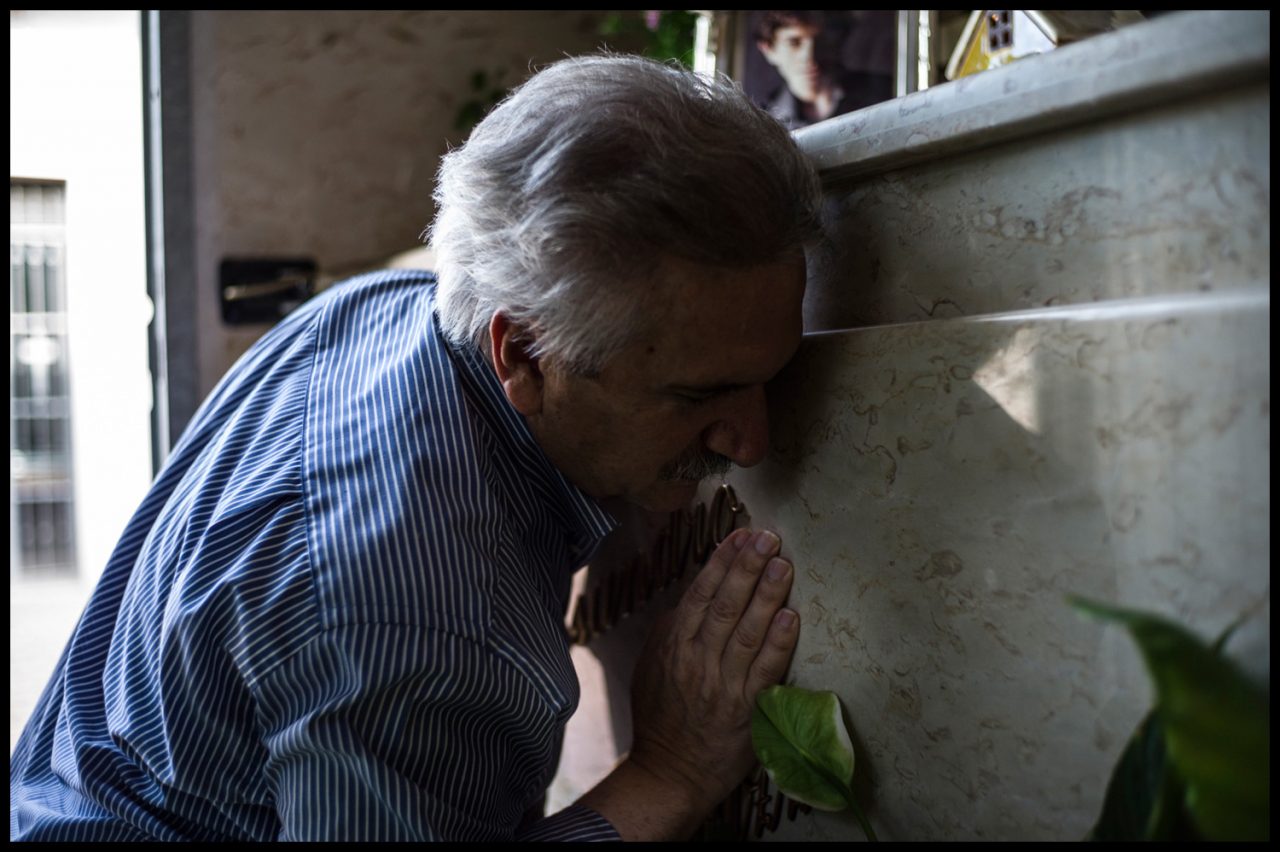

On our last day, we spent time with Aurelio Rebuzzi, whose son Alessandro died aged sixteen. Alessandro had cystic fibrosis, the air in Taranto quickly worsened his condition and he died while waiting for a lung transplant. Aurelio chose not to bury Alessandro in the local graveyard, as he ‘wanted him to be far away from what killed him’. Alessandro died five years ago but Aurelio still spends every single day by his tomb. From morning to night he sits and speaks to his son, he is so consumed by grief and anger towards Ilva that he has entirely cut himself off from the rest of the world. In life and in death, Ilva is always there.

Words by Emilie Harley, photographs © Gus Palmer