One part of the story is this. One summer, I gave birth to a baby boy. I have no idea how much he weighed, he was cherry-red with a suction mark on his forehead, as if he’d been hit by a baseball bat from another country into this one – an impossible home run. Dazed and drugged like a moth under the too-bright theatre lights, I held us close. He was crying, I was crying. I tried singing to him; all my half-dead brain could summon was the ‘The Riddle Song’ – an anonymous folk riddle popularised by Joan Baez and The Simpsons. But my version was cracked, warped, misremembered:

that had no stone that has no stone

I gave my love a chicken I have a chicken

that had no bone that has no bone

‘I told my love a story that had no end’, ‘I gave my love a baby with no cryen’ croons Baez in her recording. These elements had dropped out of my rendition. Unnoticing, I circled around on this wheel that was – it felt – all I had to give: a confession to the small crying tuning fork I was holding, a stylus. Around me, what seemed like hundreds of midwives in green scrubs were carefully rearranging my body beneath my shaven pubic hair, while my placenta – a gory purple cow’s heart – fell into the surgeon’s hands.

There’s an image painted on vellum in Jean de Meun’s medieval poem Le Roman de la Rose that shows ‘Nature’ brutally forging a baby on an anvil. It’s not a pleasant image. The casts of babies-to-be are sat in the corner, stiffly frozen in representation almost like meanings that will get carried away.

—

What is a mother? I don’t know, but I think becoming a mother has something to do with excavation – where inside has become outside. After witnessing ancient clay figures being excavated from a canyon, Annie Dillard writes that seeing the earth ‘sliced in deep corridors from which bodies emerge, surprises many people to tears. Who would not weep from shock?’

In birth, a part of you emerges outside to become something no longer strictly part of you, but something you are in relation to. But if a baby doesn’t feel separate, neither does a mother. Half-unearthed figures. Then there’s the splitting of the pre-maternal and maternal self, canyonised, now multiple figurations living and walking around in the depths. And does giving birth have anything to do with it? You might come at the canyon from the outside, and fall in.

It’s all a riddle, a folk song, a mystery. ‘Riddles’, the poet Joyelle McSweeney writes, ‘are uncanny and dubiously maternal. Riddles issue from the monstrous and matrix body of the Sphinx herself.’ And clarity, like that which is over-illuminated under theatre lights, tells us nothing about maternal riddles, half-unearthed relations and disparate parts. Becoming a mother, relations between mothers and children – these things are fundamentally obscure; like being itself.

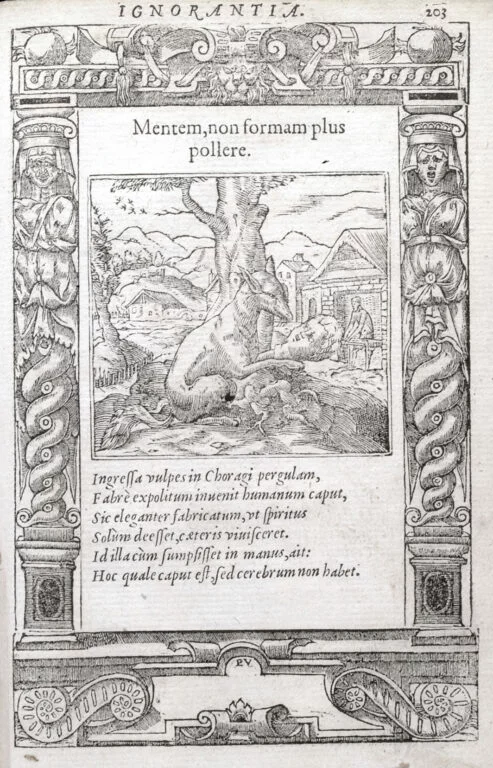

I asked myself, much later – what kind of dreamscape can assimilate all these constituents? But I was already by this time holding one – a book of sixteenth-century emblems that I couldn’t read.

And are not emblems’ baroque, monstrous frames a little like canyons or riddles to fall into?

What is an emblem? If someone ever asks you this, you can say emblems are a hybrid form of text and image that mutually interpret and reinforce each other. But you’re unlikely to say this, as it’s the kind of sentence that only gets written down – a picture made of letters. This is the space of emblems, speaking pictures, whose figures soundlessly open their mouths – something like dreams.

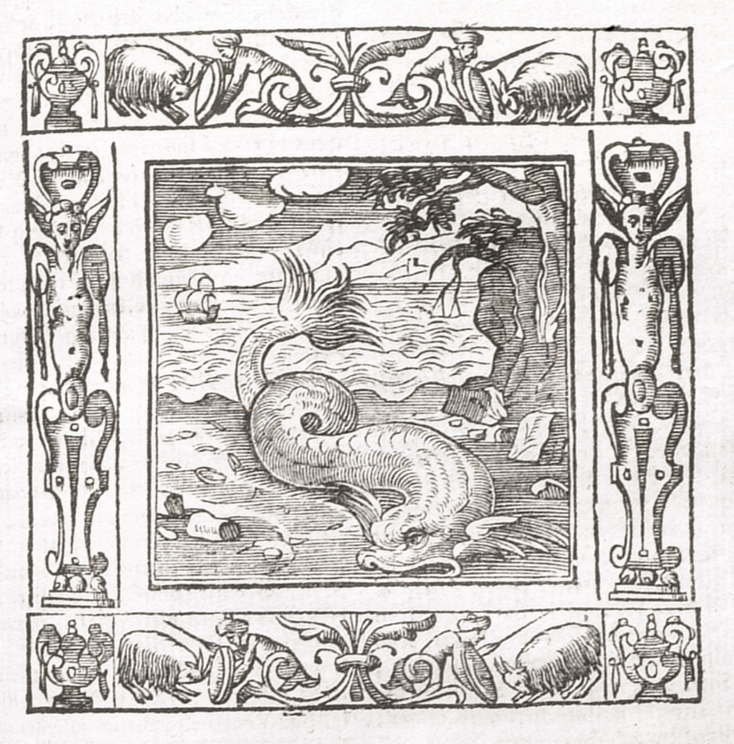

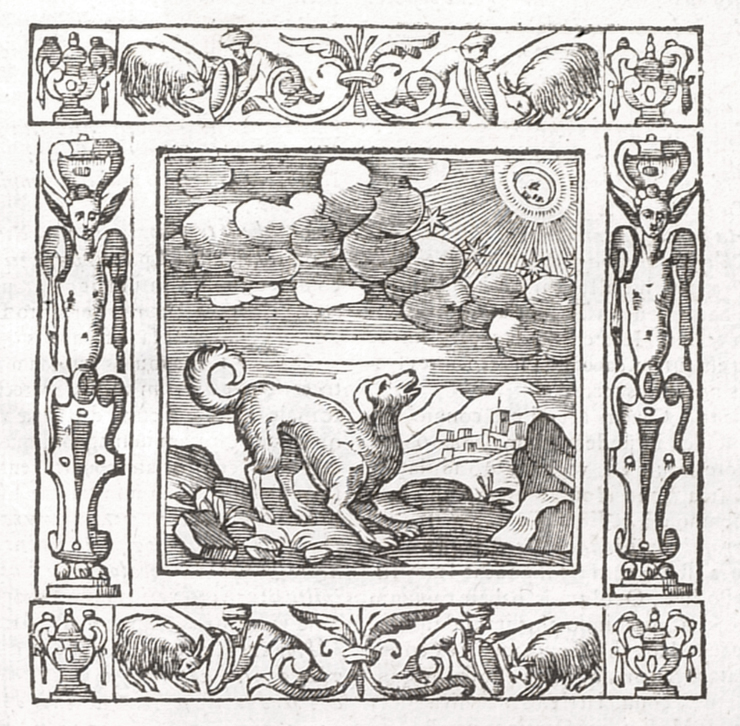

A hybrid form of text and image. Like a record cover, or a meme, or a poster. But emblems and emblem books first come from the early modern period and were mainly printed with woodcuts.

Emblems usually had three parts: a motto (inscriptio) hovering above an image (pictura) and underneath that, a poem (subscriptio). But sometimes they had just two parts. The mixture remains uncertain. Emblems were designed to be enigmatic and contemplative, a prolonged hesitation moving back and forth between text and image within a surreal frame. Like a family, thrown together as if by accident and working out how to fit. Or how, as in motherhood, you’re suddenly not your own person anymore but share your organs with someone else.

Early emblematists thought of emblems as having a body (image) and a soul (text), like a person. Or a self (image) and a body (text). A cherry and a stone, chicken meat and a bone. Nobody has ever been quite sure which bits are what. Who is scaffolding who? A refashioning of the self takes place.

What is an emblem?

What is a mother?

These are not good questions. They imply that an emblem or a mother might be a singular thing, occur as normative types, and be the same in the past as in the present – and that this present will remain unchanged forever.

Another part of the story is this. I came across emblems when I was pregnant. I couldn’t read them as I can’t read Latin, but their monstrous strangeness and materiality fascinated me. In particular, Andrea Alciato’s Emblematum liber, the very first emblem book – its four hundred-year-old woodcut printed pages bound together with stained animal skin. Like a baby, such objects bring their own times with them – planets with their own gravities and durations crashing into ours.

Just after my son was born, I applied for a funded PhD to study Alciato’s emblem book, not making any connections between mothers and emblems – at the time all felt practical and necessary. I’ve seen people say that nobody does a PhD for the money, but with it I could move out of the house I was living in, into a new home and look after the baby without having to go out to work. Fugitive planning, as Fred Moten and Stefano Harney write in The Undercommons: ‘“To the university I’ll steal, and there I’ll steal,” to borrow from Pistol at the end of Henry V, as he would surely borrow from us.’

Not that I knew anything about babies, PhDs or emblems.

Perhaps we are at our most receptive when we are in a state of obscurity, which I think of as the quality of something being not clearly (fully) known or understood, rather than of inadequate intelligibility or irrelevance. An open threshold.

—

Some etymologies that lead us into the maze:

Obscūrus, the Latin for obscurity, means dark, darkness, shadowy or dim forms; to obscure (it can mean itself); indistinct; unintelligible; uncertain; not known or recognised; close, secret and reserved. Obscūrus also has ancient etymological roots in the Sanskrit sku, to cover. The Italian oscurare (to darken) is associated with blurred, shadowed vision and techniques of visual representation such as camera obscura and chiaroscuro.

In Old English, obscurity has affiliations with scēo (cloud) and scúwa (the shadow thrown by an object, shade, darkness, protection).

The meaning of the word emblem is derived from inlay, as in a mosaic, an ornament – from the Greek ἔμβλημα, meaning a detachable ornament, the insole of a shoe, or a cultivated branch grafted onto a wild tree, or metal decorations fixed onto tableware, or badges.

—

Emblems began when Alciato (1492-1550), a jurist, philologist and one of the most famous lawyers of his day, translated epigrams from the Greek Anthology into Latin, which had been freshly discovered at a time when manuscripts were literally dug out of the ground. The Greek Anthology is a fragmentary collection of thousands of Hellenistic epigrams first inscribed on stone. Alciato, a lover of unearthing archaeological relics and collecting Latin inscriptions engraved on monuments in his native Milan, was perhaps driven by an unease that these artefacts would irretrievably re-disappear if they were not documented and somehow revived, or perhaps he simply encountered them. Perhaps he needed them, perhaps he wasn’t entirely sure why.

Alciato also translated the epigrams for his erudite friends, intending them to be read as entertaining trifles and tokens of esteem as ‘paper gifts’. These ancient relics and fragments were heaps of debris, junk, but also contained alternative topographies, a refuge from but also a way to mirror the present – its wars, plagues and political ferments. Often the translated epigrams or emblems are didactic, with moralising mottos – a Renaissance version of motivational Instagram posts – although I find this didactic aspect of emblems extremely dull.

Alciato didn’t invent emblems as they eventually became. His private manuscript of translated epigrams fell into the hands of a Dutch printer who decided to print them in 1531, commissioning an artist to add woodcut illustrations as he thought this would make them more popular. It’s not clear how this happened, but at the time book production was out of the hands of authors who often found their own books altered beyond recognition in circulation. A lifelong snob, Alciato was horrified and embarrassed by this, thinking the images to be poor quality and downmarket. Since the book was already out, he hurried to commission a new version with better pictures. The whole thing snowballed. He wrote new emblems (nearly half of the final 212 emblems remain translations of the Greek Anthology) and commissioned more images. After Alciato’s death, the composite of what had become his emblem book was reprinted, translated and retranslated into different languages until 1621 – my favourite edition – and other emblematists began writing different emblem books across Europe. Emblem books are self-replicating textual worms. They harbour a form that seems to intrinsically invite additions and reframings, just like how memes spread their wings across the internet now.

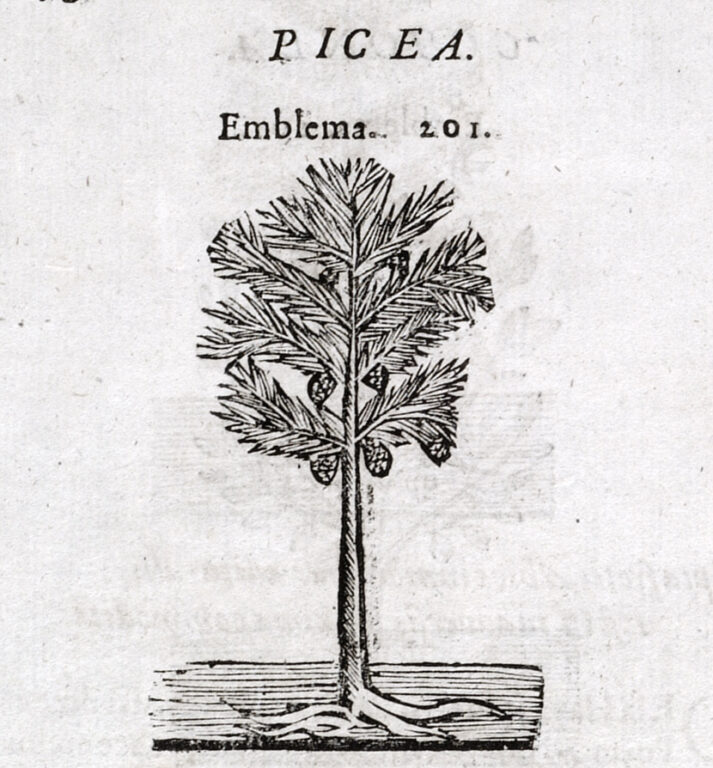

Alciato died single (possibly widowed) and childless, after several years of deteriorating health, including gout. The emblems were a sideline and not that popular until after his death. Towards the back of the Emblematum Liber, the emblem ‘Picea’ (Pine), reads

At picea emittat nullos quòd stirpe stolones,

Illius est index, qui sine prole perit.

[But the spruce, because it sends up no shoots from its stock, / is a symbol of the man who dies without progeny.]

Illius est index. Index, the Latin dictionary tells me, as well as meaning ‘sign, token, proof’ also means, ‘informer, tale bearer’ and the ‘hand/needle of a watch’.

There’s something visceral about woodcut printing, which draws attention to writing as a kind of picture, a book as an object, a thing. By reprinting bits from ancient manuscripts, emblems prised textual residues of animals, plants, symbolic and decorative objects out of fragments of cultural memory. These already-composted texts and images became new pages and were then resituated elsewhere into other things: on frescos, on woodwork, on banners. In doing this, emblems revived these absent presences in the tapestry of the world.

When I began studying emblems, I moved into a one bedroom flat. At night, I anxiously slept on the floor next to my son’s cot and held his hand through the bars, because he woke up all the time, as babies do. I didn’t sleep very much. I watched the greyness that comes between dusk and night, and night and dawn. That fuzzy, dancing greyness that speckles and blurs the past and present. Sometimes, if I felt very lonely being housebound, I would lift the Bakelite-green receiver of the front door buzzer and listen to the wind and the leaves moving outside.

I was lonely, but I had my son and I had an unreadable book, written by a spectre called Andrea Alciato – an absent presence, a residue that had changed my surroundings. Three parts.

A cloud of unknowing.

More fruitful accidents and misreadings shaped emblems: in the early modern period as during antiquity, hieroglyphs (another form of picture) were misread as ideograms of divine letters rather than as phonetic writing. They were thought to contain hidden prophecies and signs, deliberately veiled so that the unwise might not misuse them. Alciato compared his emblems to hieroglyphs, saying that while words signify and things are signified, sometimes things (objects) signify too. His emblem book became called the Emblematum Liber. Another version of liber, libellus, refers to a papyrus scroll.

Later, devotional emblems written by Jesuit priests would expand the enigmatic and metaphysical side of emblems, seeking to gesture towards that which is veiled and hidden from this world.

Mothers, too, are required to be vigilantly interpretative. But what they interpret is forever hidden from them – especially in early motherhood when children cannot speak, or even see. Are they sick or healthy? Are they hungry or tired? What are the signs? Like sixteenth-century Jesuit priests, mothers are interpreters of the unknown, that which is in obscurity.

To help yourself perform single motherhood you might also tell the time through objects – as the French Republican Calendar does – rather than linear clock time, which has become useless to you as small children rightly do not care about it. Another kind of time to tell the time, when day is night and night is day in the greyest canyon. Sometimes, things and not words signify.

You might need a needle, a fir needle, an index, a tale bearer, a witness. They might need you.

But. Would we really want babies to answer back? Do we truly want to know the answers to our questions? Sometimes, it is better to not know what is behind the veil, decode the sign.

—

With all its parts and objects, an emblem book is an imaginary museum, a display of unity. But more often than not, what they display has been removed.

Renaissance humanist patriarchs like Alciato liked to substitute problematic real things for metaphorical things – like replacing women with ‘equally “precious” objects that metaphorically assume feminised values’, as Karen Pinkus observes in her study Picturing Silence. As self-replicating textual worms, emblems were therefore also self-sufficient units that made anyone who wasn’t a humanist patriarch obsolete, an attempt to retain control. Emblematic woodcuts, heavy furnishings, wrought-wood inlay inset with more visions of objects, animals and plants, bound with vellum hunted for in the woods, crafted objets d’art.

Half-unearthed figures in the ground. Ill-thought through and hasty burials.

When I started to look closer at and read the emblems in translation, I didn’t really like what I found.

Alciato’s emblems are often offensive, vulgar and misogynistic. Some are obsequious displays of flattery, some are bitchy, some are just complaints. I can’t really know what his poetic style is, but it’s described by those who do as ‘rough’. It probably should have been obvious to me from the start, but the emblems are rooted in a violent imperial nostalgia for an imaginary golden age of antiquity that never was.

When constructing their models of ‘Rome’, Renaissance humanists didn’t consider their translations and adaptations of fragments from antiquity as stealing. Rather it was imitatio, a following in the footsteps of, or sometimes a repristination. The way you might repaint a room, or use garbage to build a new structure.

Is taking once more from this imperial dumpster a form of repristination or reparation? For Eve Sedgwick, the reparative reader ‘helps himself again and again’. Sedgwick’s model of reparative reading aims not just at multiplicity of meaning, but a form of survival: ‘What we can best learn from such practices are, perhaps, the many ways selves and communities succeed in extracting sustenance from the objects of a culture – even of a culture whose avowed desire has often been not to sustain them.’

If I borrow an overgrown brick from a prison to build a house, if I borrow something not meant for me but no longer used, if I borrow a brick that would have been thrown at me, is that brick tarnished forever? And if so, what brick is not?

—

These parts and structures, obscuring each other in their unifying display, making absences present and presences absent.

Emblems: a way to replace things and become self-sufficient, for one reason or another?

Emblems: a way to assimilate things and renounce self-sufficiency, for one reason or another?

—

Alciato considered his emblems to be sourced from history or nature, as if the world was a book to be read. This variant of Biblical exegesis might seem dated, except when we consider ecological interconnections – how climate change, a curl of pink wool, a crumpled packet of crisps, a toddler’s cardigan encrusted with flour, laptop wires, the flies at the window, the cloudless sky, are all interrelated and enmeshed in a dizzying obscurity.

Emblem books are like misleadingly-miniature hoovers of non-serious or occult rubbish, generically illegitimate – for Odette de Mourgues, the emblem is ‘objectionable, as a substitute for another art’. For Schopenhauer, they’re ‘silly and absurd’, relying on arbitrary connections. There’s really nothing that an emblem can’t depict or suck up. There are devotional emblems, moral emblems, satirical emblems, love emblems, alchemical emblems, esoteric emblems, libidinous emblems, philological emblems. Emblems can be found in rhetorical manuals, educational treatises, dictionaries, natural history books. Sometimes they hoovered up the whole world – The Myrroure of the Worlde was the title of William Caxton’s first emblematic encyclopaedia.

One of Alciato’s own emblems is ‘Nunquam Procrastinandum’, or Never Procrastinate, which shows an elk that seems half-accidentally to be kicking its family sash into the mud. In the text, Alciato generously compares himself to Alexander the Great, who performed so many exploits in a short time: ‘“By never wanting”, he said, “to postpone.”’

Hastily I rose in the early hours and hastily I turned on CBeebies and hastily we went to the park and hastily I put fishfingers in the oven and hastily I wrote and wrote and hastily I waited for time to pass, let it not be postponed.

But, hastily too I gazed at the carpet inflorescent with wide-eyed plastic toys, my son’s face asleep and awake, my stacks of forgotten books, images inside the lit screen of my phone that never went out, nasturtiums opening their orange sails in my garden, full bin bags like dark organs by the door, hastily I hoovered them up inside the composite of experience and I saw how at night, through the lens of sleeplessness and greyness, all seemed to dissolve and coagulate into other objects entirely, into another world that was no less true.

What if there are two worlds? One the world of images, the mundus imaginalis as Henry Corbin envisaged it, laid over and adjacent to this one – where there is no locale, no time and no laws. It comes to us in greyness, in anxiety, in obscurity, when we suffer or desire.

What if there are three? I read that physicists think that our universe might have a shadow twin that runs backwards in time. An anti-universe. Are the dead rising backwards always about us? Do they live in images, as seeds of that other life?

Worlds like a bunch of dark grapes in water sinking slowly downwards?

—

The weight of single motherhood is this: at times, and perhaps for long stretches, no-one is watching you perform the most emotionally and physically demanding work of your life. At such moments, everyone needs a witness.

To be witnessed is not to be looked at, but to be seen – as in the analytic relationship.

The more I worked and wrote, I felt the spirit or figure or presence of Alciato was there – had come as if from another world into mine, when I needed it. And the more I felt this, the more I began to wonder who this spirit was. Who is Andrea Alciato? A projection? A spectre? A material residue? The historical Alciato? A Jungian archetype, as when the self is split into many figurations inside the canyon of motherhood?

The problem of how to make the dead speak – but not too much – was a major obsession of Renaissance humanists. They had encountered Classical stone sculptures with intact mouths, ears and eyes, and considered them to be the start of a transhistorical conversation. As speaking pictures, emblems sometimes use ekphrasis to make images of these statues speak. Often they use prosopopoeia – a rhetorical trope derived from prosopon poien (to confer a mask or a face): a poetic fiction of ‘coming to life’ through speaking objects and figures.

There’s a painted portrait of Alciato that he may be referring to in a letter to his friend, the historian Paulo Giovio, which he says portrays him as ‘somewhat more comely in feature than I may be in reality’. Elsewhere, Girolamo Cardano describes Alciato as portly, with bulging eyes.

The portrait is definitely more flattering than this.

In it, Alciato is twisting a handkerchief in his hands and looks extremely sad.

A record of a mood. Emblems as well as being hoovers, are records of records. Lonely people know how important it is to fill silence with speaking. I started to be aware of how much I repeated and misheard records – mondegreening. I listened to a lot of world music, gradually amassing a kind of complementary discography to my reading and mothering as I moved about the house.

In the uninterpretable, in listening to speech that was obscure to me, I could hear the spirit of what was haunting me. I wanted to be close to it, but I didn’t know what to say back – or what it could even say to me, about my life. In Alciato’s emblem ‘The Wisdom of Man is Folly to God’, the figure of Cecrops (half-man, half-snake) says, ‘Quid dicam?’ [What can I say?]

What can I say? In the end, I decided the spirit is my Andrea Alciato. I’m always glad their name is Andrea, neither male nor female. This spirit is a ‘no-thing or no-body or No One, a monster constitutively composed of multiple parts’, as Rachel Zolf writes in No-One’s Witness: A Monstrous Poetics.

A monstrous riddle, a distorting mirror, like a mother?

—

Like Schopenhauer complained, the connection between text and image in emblems is arbitrary – and always moving. Continual mistakes, negotiations, adjustments and meanings, like learning how to be a mother and how to be a child. A text and an image, an image and a text, dependent on each other for meaning.

But are accidents arbitrary? I’ve said that emblems’ lineage was accidental: a printing mistake, misinterpretation, found fragments. Alciato didn’t invent the emblem and this ever-changing material process continued: the image, which has such an impact on an emblem’s message, was always determined by a third party – the illustrator (who did not speak Latin), the translator, the publisher, to huge alterations in effect.

Plants and trees were important too. Woodcut images were reused from herbals (compendiums of plants) and other emblem books. Around the time woodcut printing fell out of favour, emblem books disappeared, considered by Enlightenment readers as irrelevant forms of knowledge. To this, as modern readers, we might add sun fade, the holes of beetle larvae and silverfish chewing, marginalia and skin bindings as marks and distortions onto the texts – animal contributions. Fortuitous errata?

In renouncing accident, lies acknowledgement.

To say I could have navigated the greyness of early motherhood or study without the support of my son’s father, my childminder, family, playgroups, friends, mothers, kind strangers, would be deeply misleading. I was lucky and am grateful. As they say, it takes a village.

—

How many meanings might be ascribed to emblems? As I read more, and as I looked more, what I saw were plants growing out of their frames, birds and bats in flight from solidifying, deathly representations and escaping into the world. Now I look at them again, I see the figure of ‘Silence’, with his finger to his lips, has his back turned to the wall through which we can only hear the faintest of sounds.

—

There’s something about obscurity that changes our understanding of the world or worlds, like the strange obverse illumination of looking at an image made by a forgotten artisan surrounded by an unreadable language, or singing a misremembered riddle song by an anonymous folk author at a birth.

This is because obscurity is a quality in itself – the quality of an unknown quality, a meta-quality of a hidden thing. That which is revealed, then revealed, then revealed, but always never more than slightly.

Revelation, Cardinal Newman says in a way that makes me think of woodcuts, ‘is like the dim view of a country seen in the twilight, which forms half extricated from the darkness, with broken lines and isolated masses.’

This dim, grey light, most acute during nursing hours, hours of chronic coughs and stomach bugs, has always percolated through mothers at night. Half-unearthed mothers. Mothers in a state of feverish anxiety attempting to interpret that which cannot be known, or shall we say, in a state of logical obscurity? How things are?

Isn’t knowing itself marked by obscurity?

Leibniz thought so, seeing ‘confused knowledge’ as the clearest form of ‘clear knowledge’. Johann Gottfried Herder, excited by Leibniz’s ideas, declared it a foundational quality: ‘The entire ground of our soul are the obscure ideas which are the liveliest and most numerous . . .’

Poets have always known this form of knowledge – it’s called poetic logic.

Emblem by Lucy Mercer is out now from Prototype Publishing.